FOMA 29: Modest Brutalism in Turkey

This FOMA will present the Brutalism in Turkey between the 1960s and 1980s. Born as a new esthetic tool and a strategy of form, has been according to Banham (1966) diversified and become widespread by different interpretation in different geographies. In this respect, what is the place of Brutalism in Turkish architecture, which has most of the time turned into a strong esthetically interpretation?

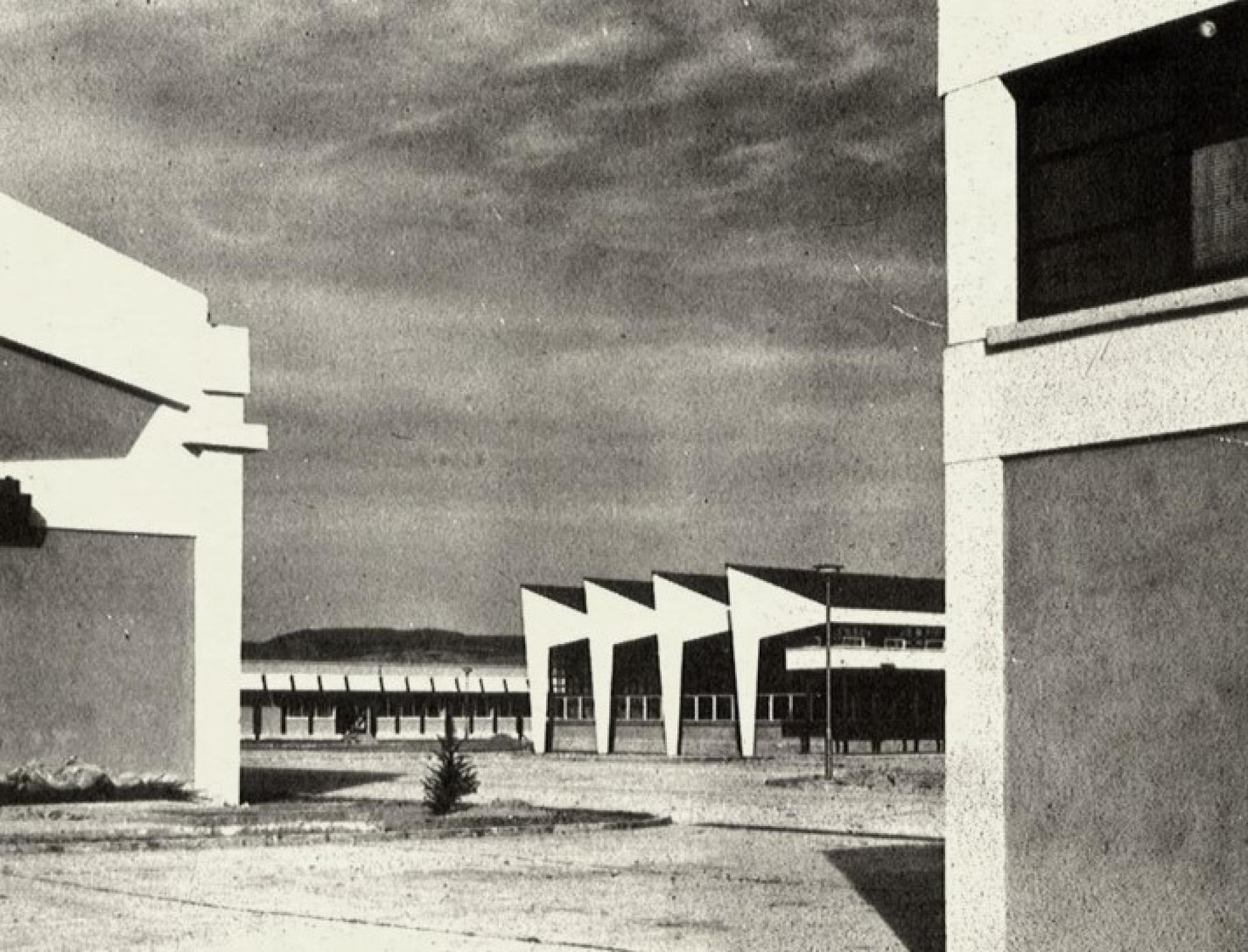

Dosan Canning Factory became one of pioneers in reflecting the developments of the building technology sector into the architecture. | Photo by Reha Günay

It has been built with concrete carcass system. | Photo via Mimarlık Dergisi

I will answer this question with five buildings of varied scales and functions and so examine different variations of brutalism. The 1960s can be described as the heydays of Brutalism points at a period of versatile economic, political and social change in Turkey, which was triggered by some certain interior dynamics and exterior factors (Keyder, 2010) [1]. Development politic and industry were the determiners of architectural production in the country. According to Tekeli (2007) the establishment of the manufacturing factories built with the state and private initiative also affected the Turkish architecture in the 1960s. As Yücel (1984) states in the text “Pluralism takes command: the Turkish Architectural Scene Today” that the pluralism determined the character of the era, some factors such as developments of the building technologies and diversified building materials contributed to the variation of architectural attitudes [2].

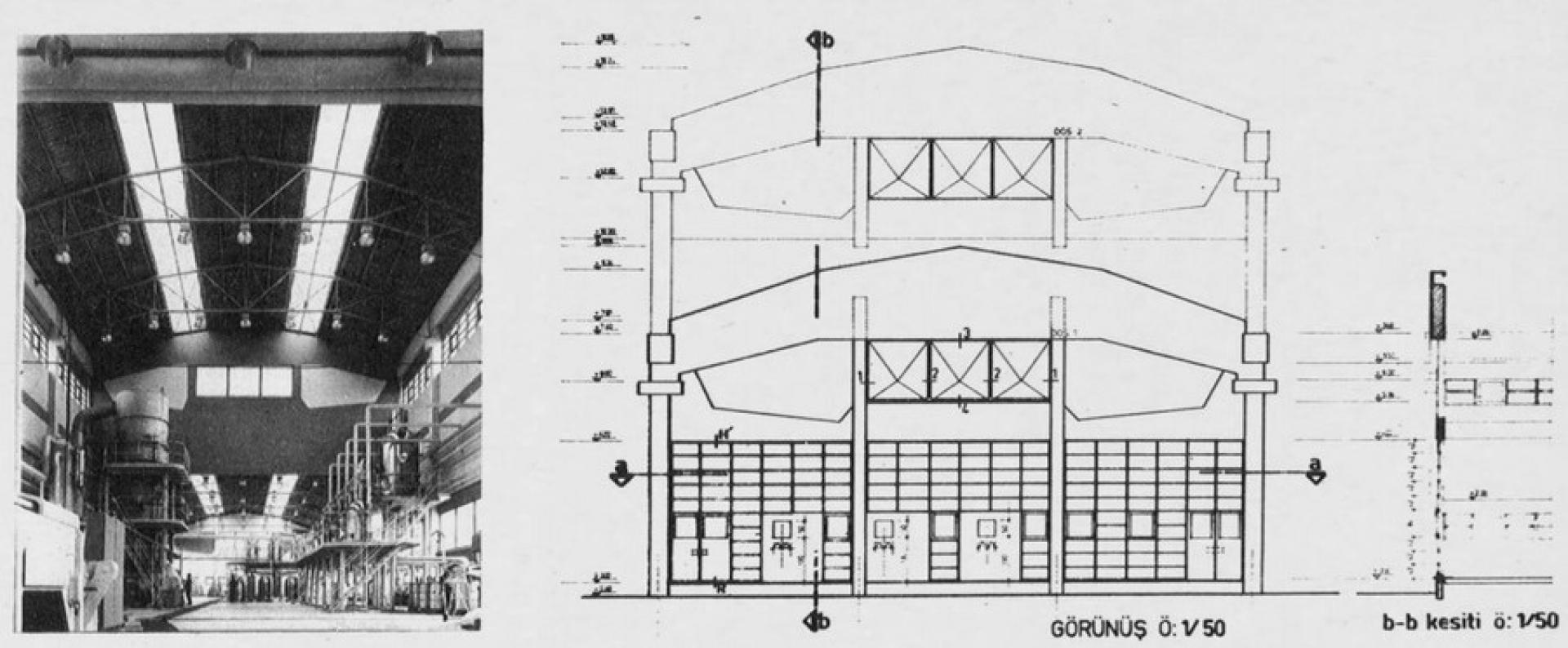

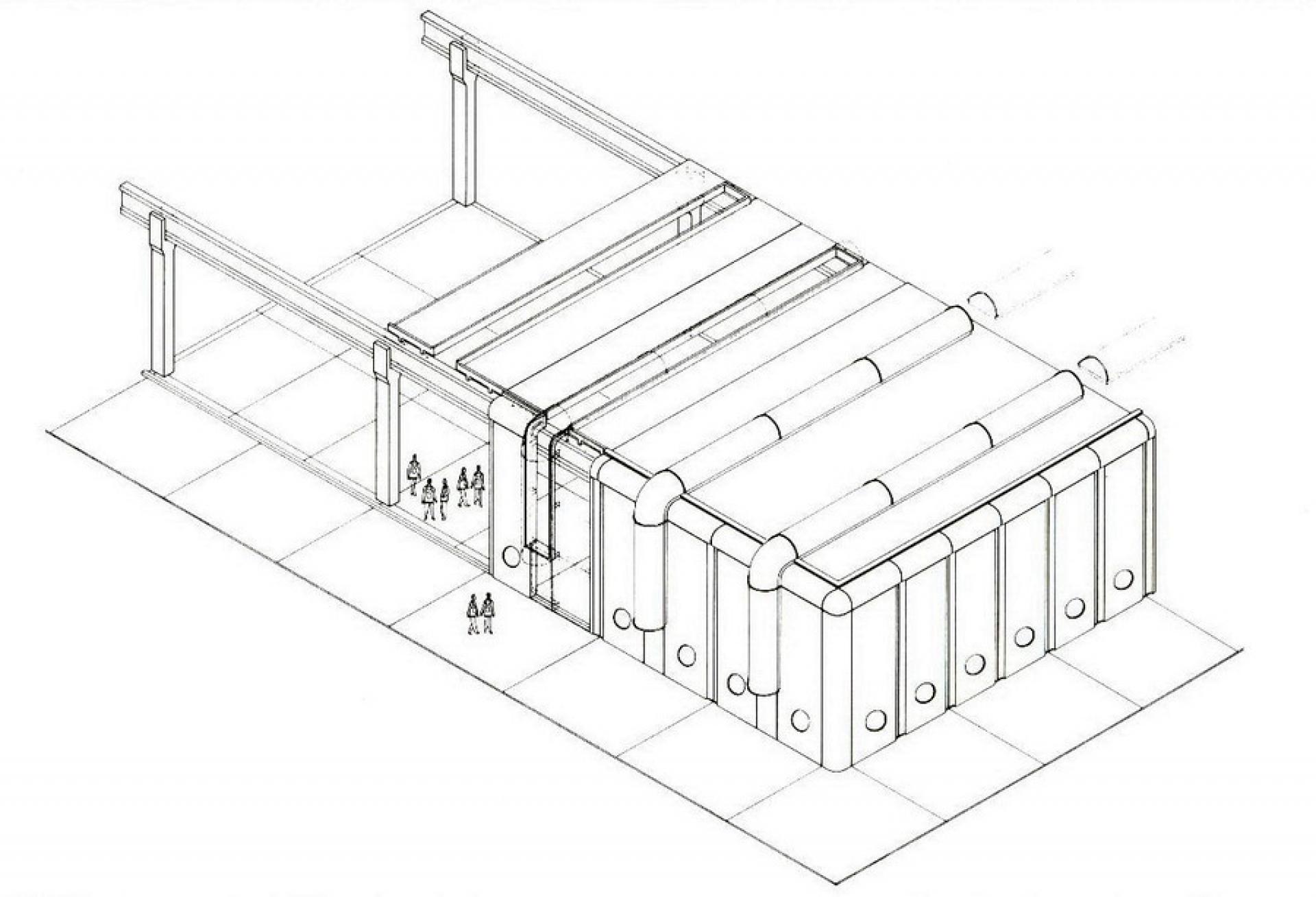

The Lassa Tire Factory, the biggest industrial building under a single roof, was the largest brutalist buildings in Turkey. | Photo via Archive of Tekeli & Sisa

One of the most important changes has occurred thanks to the free market economy; it was the emergence of the new employers and, as a consequence, that of the new building typologies. While the most influential employer before the 1960s were public institutions, after the 1960s private sector was involved in the architectural production and brought some new demands along. Thanks to the changing profile there came also a change in the building materials. Architects enjoyed an opportunity for diversity thanks to the big holding buildings as well as the requirements of factories, which entailed new typological, structural and technical solutions.

The factories built in the 1960s in so called Turkey’s Industrial Revolution, refer to a specific architectural production through which architects played around with new structural opportunities. In their projects they created new design strategies and realized them with new building technologies and materials. Akcan (2010) is convinced that despite the scarcity of building materials, making architectural design thanks to the new building technologies has become one of the design motives of the period.

The important element of the 300-meter facade of the Lassa Tyre Factory are sectioned polyester skylights on the roof. | Photo via Archive of Tekeli & Sisa

The factories became pioneers in reflecting developments of the building technology sector into the architecture. In that period appeared a need for the new solutions of the structural and spatial constructions. The need for covering wide open spaces for instance entailed the use of industrialized building technologies. The practice of designing and building factories have helped the development of building technologies. According to Batur (2005) was important to gain experience in the utilization of prefabricated constructions. Modular systems were brought along by the industrialized building technologies and consequently repetitive roof and facade elements supported the tectonic expressions of the buildings. In this sense, the factories became the significant examples of brutalist architecture thanks to the bold exposure of their structural units and also to the aesthetics of the steel beams, foldable plates and shell structures.

A module of the Lassa Tyre Factory. | Photo via © Tekeli-Sisa Architecture

The factories built in the Marmara Region have been designed in brutalist style and they became subjects of some technological experiments in Turkish architectural practice. For instance, the Dosan Canning Factory, which has been designed by Aydın Boysan and constructed in a short period of time, is one of the qualified examples. The main idea was the creation of the architectural form by following the structural elements. The factory has been built with concrete carcass system; in the dining hall the folded plates shape the walls and are connected to each other with columns, which get thinner towards the floor. Comparing with the other spatial units, this structural solution has given the dining hall a stronger architectural expression. While steel beams have been employed for the roof structure, which expands over a big opening, fiberglass plates have been used for the light shaft. In his review of Turkish architectural production, Boysan points out the scarcity of building materials as a peculiar issue to the country. He also states that the required profiles for the steel structures were especially hard to find. The material crisis has been mentioned often by the other architects from the same period; they say that due to the conditions they had to employ creative solutions in order to have the aimed effect in their design and to compensate for this scarcity.

Dosan Canning Factory by Aydın Boysan (1971) in Yenisehir creates an architectural form by following the structural elements. | Photo by Reha Günay

Doğan Tekeli and Sami Sisa designed series of factories for the private sector. In the evaluation of this process, they have complained that the employers actually limited their designs and were not really committed to the process as their designs were found too experimental. It is safe to say that architects in general like to create a new and unique architectural language with the help of new building technologies, but it is hard to convince employers to use those new ideas in their buildings. Nevertheless, the architects somehow found a chance to develop ideas in factory projects since they were located out of the cities. The employers did not concern themselves with how the factories would look as much as they did when it came to holding buildings, which located in the city centers were considered as prestige buildings.

Polyester skylights, brutal concrete facade and circle windows break the monotony of the facade. | Photo via Archive of Tekeli & Sisa

In the 1970s monumentalism stands out in the Turkish architectural production. Bearing the signature of Tekeli Sisa Architects, the Lassa Tyre Factory in Izmit has been designed in line with the zeitgeist of the era. It is known for its scale and was considered as the biggest factory built under one single roof. The most important element of the 300-meter facade is the semi-circle sectioned polyester skylights located on the roof. While they make a curve down on the side facades and create a rhythm, they provide daylight for the inner places. Those polyester skylights, brutal concrete facade and circle windows at the eye level are the main architectural elements. Those architectural elements break the monotony of the facade and bring a new identity to the building.

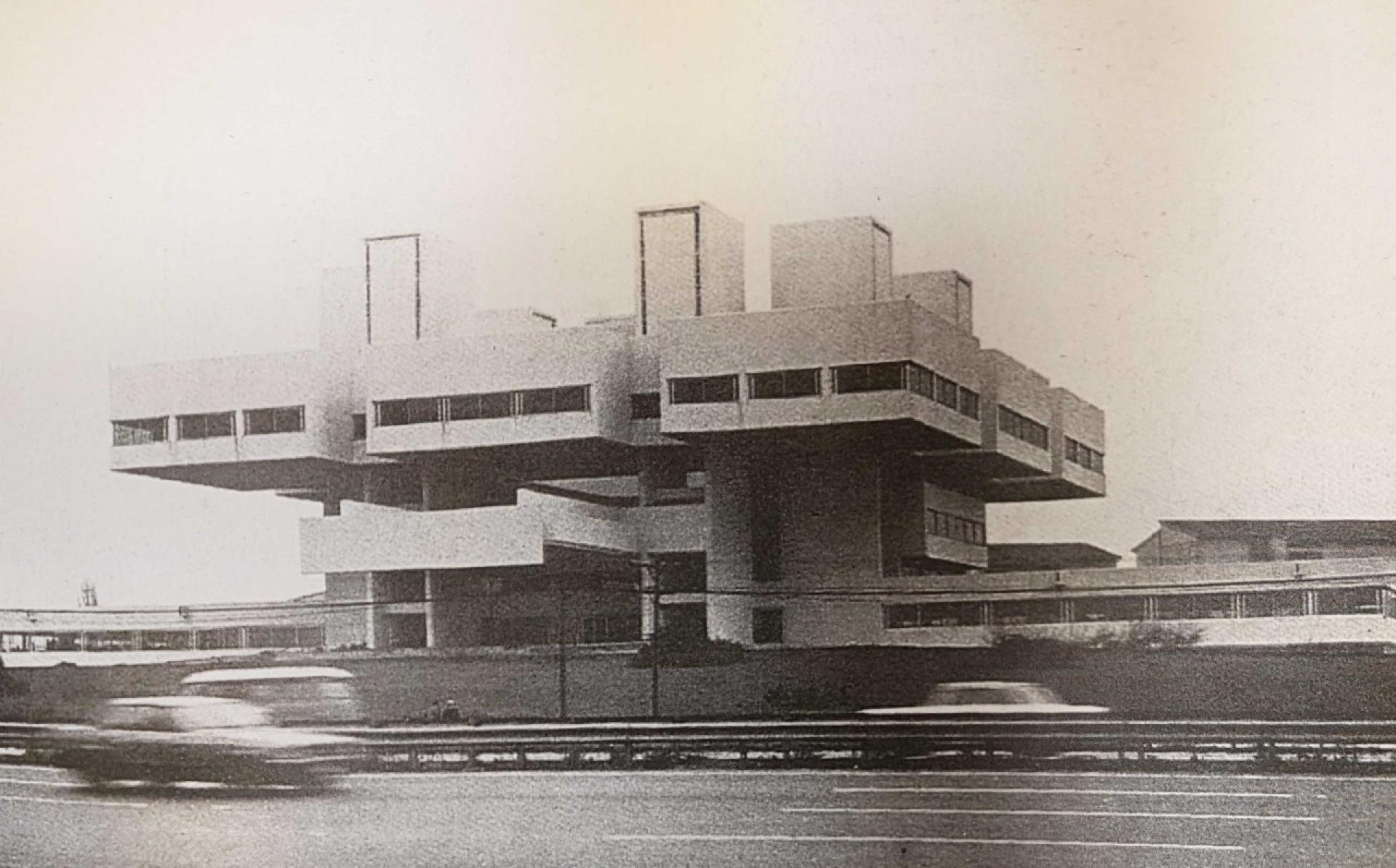

Tercüman Newspaper Office Building with its out of the box, unconventional design and bold structural expression. | Photo via Modern Turkish Architecture

The experimental approach, which was predominant in the factory designs gives way to a cautious aesthetical search in other building types. This certain kind of caution shows itself both in the ways of material use and also in the search of structural design. Compared with the brutalist architecture of the neighboring countries, it is rare to find bold and courageous architectural designs in Turkey, where the limits of structural elements were pushed. One of the boldest examples from this period is the Tercuman Newspaper Building in Istanbul. Its neighborhood was not developed and the building plot was not surrounded by any buildings. Thus the building had an idiosyncratic plastic effect which could be perceived from a distance. Located next to one of the main arterial roads in Istanbul, even from a moving car it catches the eye thanks to its alluding plastic effect. The main element, which creates this plastic effect is actually the structure of the building. Thanks to these towers it was possible to create a continuous space inside the building.

General view from the motorway in 2018. | Photo by İdil Erkol Bingöl

Istanbul Advertisement Building has been located as to surround a small-scale historical building without coming into touch with it. | Photo by Omer Yılmaz

The 1970s developed two dominant buildings types for the private sector and for holdings. In both has been reflected brutalist approach with concrete surfaces and monumental aesthetic expression, which was brought along by segmented mass composition. One of the iconic building is the Istanbul Advertisement Building. The brutalism is expressed with the vertical concrete surfaces and virtual exposure of the structural elements. Located in an area full of historical references, the articulation of the volumes plays an important role in the formation of the sculptural expression of the building. Its segmented mass structure is one of the new characteristics, named as brutalist formalism.

Istanbul Advertisement Building. | Photo via Modern Turkish Architecture.

These buildings have a special importance thanks to the structural quest of the architects and the use of new technologies. However, in housing projects is not used industrialized construction technologies in the big scale as for the construction of the factories (Yücel, 2007).

Brutalist Kamhi-Grünberg Twin Houses. | Photo by Idil Erkol Bingöl

The Kamhi-Grünberg Twin Houses is one of the examples of the brutalism. The building has been organized in two independent units under one roof. Separated by a garden, these twin houses have been built around two-story atriums, which connect the garden with the sea, thus provide a good airflow. The association of the inner and outer space is important for the design: the connection of the interior space and the garden is provided through the use of big glass surfaces and aluminum framed windows.

The wooden frames at the top of the windows and wide canopies represents traces of traditional Turkish house. | Photo by Idil Erkol Bingöl

Known for his meticulous works for architectural details, Utarit Izgi searched for new solutions with the support of clients. The roof structure has been carried with steel beams instead of using load bearing columns in the terrace. The terraces upstairs have been carried by the roof, thus the continuous view is provided in the rooms and terraces. Considering the material scarcity of the era, it is striking that the architect pushed the boundaries and decided on using white cement. In the process of pouring concrete, with the help of two compartmented mold, the outer parts have been constructed with white cement-aggregate, and the inner parts with standard cement-natural aggregate. The wooden window frames accompany the concrete structure, steel roof and wide glass surfaces.

As a part of the brutalist expression, all architectural elements have been exposed on the facade. | Photo by Idil Erkol Bingöl

The five buildings reviewed in the article, the Dosan Canning Factory, the Lassa Tyre Factory, the Tercuman Newspaper Building, the Istanbul Advertisement Building and the Kamhi-Grünberg Twin House, are considered as the different reflections of the brutalist approach. In spite of the technological developments and the transformation of local building practices, it was quite rare to come across with courageous architectural designs, which pushed the limits of the building technologies. Most of the attempts to build such projects unfortunately remained on paper. In this vein, when compared with the world scale, the architectural production in Turkey has been very cautious. Brutalism gave way to a new architectural expression, which emphasized the form through the usage of decorative elements. As Banham (1966) has indicated, the brutalism once was swiftly in the ascendant but lost most of its allure just in a decade.

Notes:

[1] On the other hand takes the victory of Democrat Party in the elections of 1950 as a turning point in the history of Turkey and mentions that the changing process has started in the 1950. In that period, a general growth in Turkish agricultural production, an increase in the gross national product and 50% increase in the export have been witnessed and between 1951-1955 the production of cement and cotton weaving doubled in size (Zürcher (2008): Modernleşen Türkiye’nin Tarihi, İstanbul : İletişim Yayınları, p.327)

[2] Yücel (2007) states that one of the main design issues of the era was the relation to be built between the new building technologies and local values, identity arguments and the architecture which was inspired by the vernacular. For further information: “Çağdaş Türkiye Mimarlığı: Tarihselciliğe Karşı Tarihsellik”. (ed.) T. Korkmaz, 2000’lerde Türkiye’de Mimarlık: Söylem ve Uygulamalar, (pp.165-173). Ankara : TMMOB Mimarlar Odası Yayınları.

İdil Erkol Bingöl (1981) studied architecture at Mimar Sinan Fine Arts University and received her Master’s Degree in History of Architecture in 2009 at the Istanbul Technical University. In 2006 she began working as a research assistant at Istanbul Bilgi University, Faculty of Architecture, where is still teaching the history of architecture, history of cities and architectural design studio. She completed her Ph.D. thesis entitled “Revisions of Modernism in Turkey’s Architecture (1960-1980)” in History of Architecture program at Istanbul Technical University in 2016. Her works are concentrated on the local modernities and the research of the modern architecture history in Turkey.