Magnetic Attraction

Wandering around Paseo del Prado in Madrid, on an area named as the Golden Triangle of Art with the vertices settled at the Prado Thyssen-Bornemisza Reina Sofía museums – furthermore can be found a singular smaller museum the Caixa Forum (in a literal translation a bank safe-box), designed by Herzog & de Meuron symbolically inaugurating the new millennium with grandiloquent aspirations at the Spanish capital.

Belonging to a banking company, also converted into an arts patronage foundation, that novel and emblematic museum’s building assumes the character of a bank safe-box in which those cultural investments are deposited, preserved as tax-exempt financial assets, and also being exposed to the public. Since the Renaissance and baroque the subjective high value of art-works began to be used for those purposes, also being increased and magnified by a competitive furore between capital cities as “attractive poles” for “finantial investors”.

Those attractive aspirations seem to be implicitly figured in the character of the building, both conceptually and materially, a magnet as its authors characterised it: “The CaixaForum is conceived as an urban magnet attracting not only art-lovers but all people of Madrid and from outside. The attraction will not only be CaixaForum’s cultural program, but also the building itself, insofar that its heavy mass, is detached from the ground in apparent defiance of the laws of gravity and, in a real sense, draws the visitors inside.”

Being sealed to the outside-world in all exhibition floors, also justified for avoiding natural lighting due to conservation requests of some art-works, the building merely opens fiscally and visually to the city respectively below and up: by the street level, where all that constructive mass rises up as if levitating, for sitting a discrete entry below; and on the rooftop, in the restaurant and cafeteria, opening to the panoramic views over the city.

The intended magnetic character of the building, starting at the street level and driving the visitors to the inside of that massive corps(e) –lodged and filling an ancient industrial building, like an embalmed corpse, of which only his bricks skin remains– by walking through a short but in-tense promenade, that leads to a cavernous public entrance and the following ascendance by those cinematic staircases as if levitating to the reception hall on the upper floor, are the subject and the focus of this short writing quest and of this photographic record.

Cinematic motion in space (and in spatial) representation

A century before, Marcel Duchamp presented one of his most emblematic paintings "Nude Descending a Staircase, No. 1" (1911) and the version “No.2” (1912).

Marcel Duchamp's Nude Descending a Staircase, No. 1" (1911). | Photo © Philadelphia Museum of Art

At that time Duchamp’s work was ridiculed for not fitting either into futurism or at cubism movements. Against a dark background the figure is represented by multiple triangles with hinges, trailed through a sequence of overlaid images like frozen in time (photograms / frames) transmitting the impression of the descending movement of a body, traversing a given space –a fragmentary representation of a staircase.

Marcel Duchamp's Nude Descending a Staircase (No. 2), 1912. | Photo © Philadelphia Museum of Art

On one hand appears to be a cubist representation with multi overlayed viewpoints, at the represented background space of action. On the other hand it re-presents a trailed figure with a vibrant combination of reflected lights and projected shadows emphasizes a futurist motion action. Despite those allusions, the alluded motion is not linear as in the futurism speedy representations but rather circular, as an elliptical motion on space over time –as well can be seen on the vertical accesses of the museum – more in accordance with an oriental conception of space-time that just was admitted in Western culture after Einstein’s theory of relativity (first proposed in 1905) with the refutation of an absolute linearity of space and time.

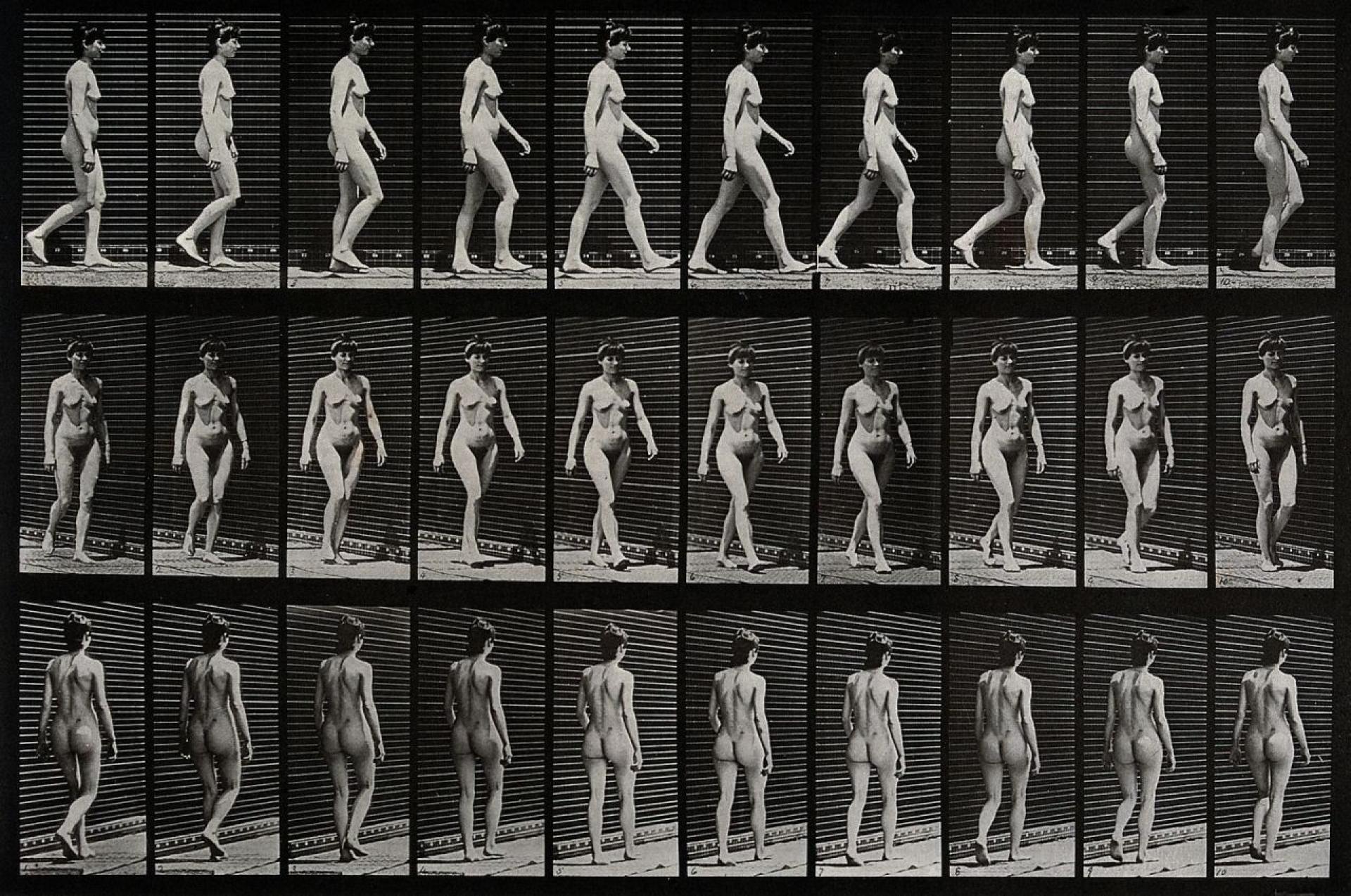

Eadweard Muybridge's Animal Locomotion: Plate 92 (Nude Woman Ascending Staircase), 1887. | Photo © Huxley-Parlour

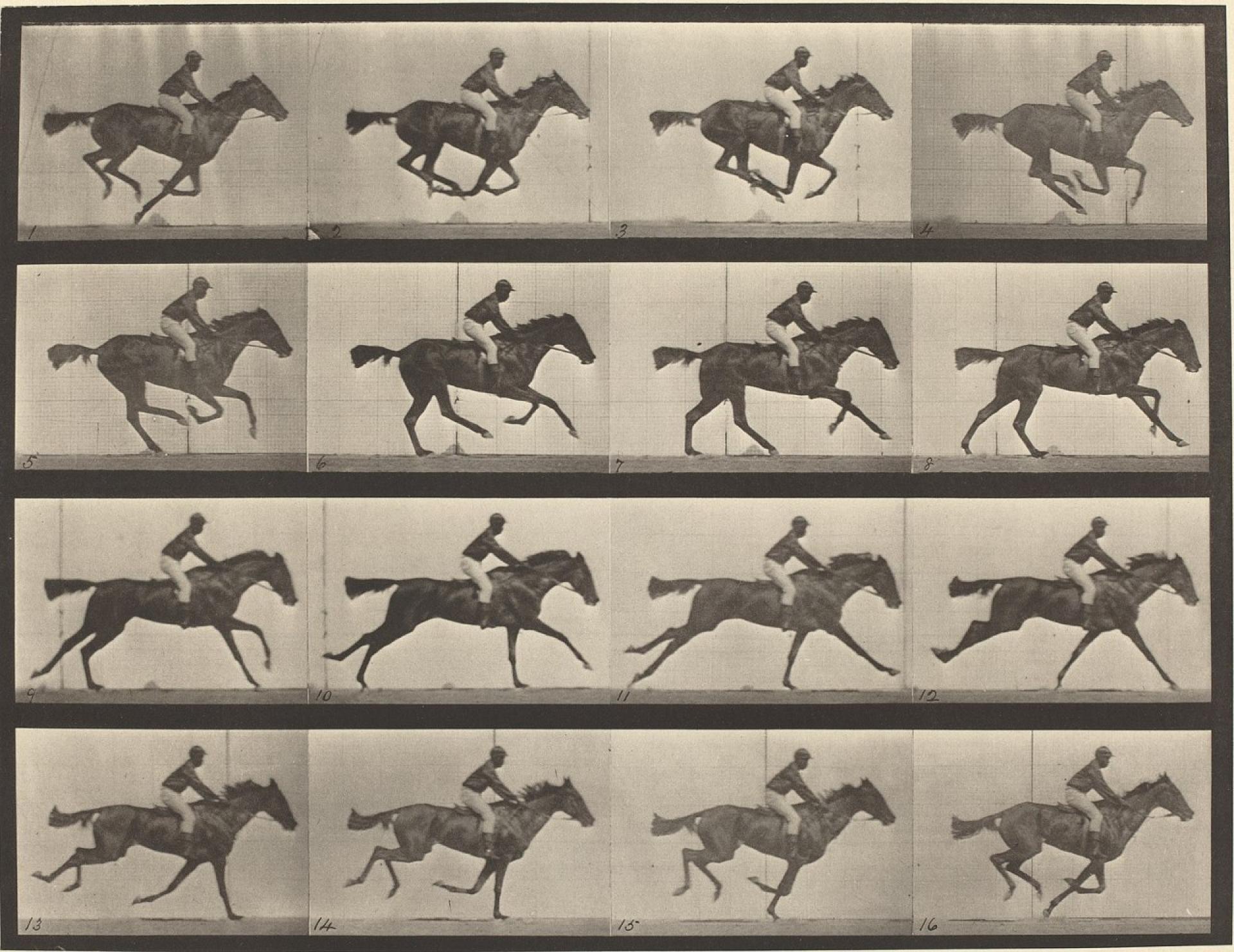

Those Duchamp art-works seems also to be implicitly in line with the primordial photographic studies on locomotion behind the beginnings of cinema, still so far as in 19th Century, mainly with Eadweard Muybridge’s female nude motion study (Woman walking downstairs, 1887) or the Horse Racing (1887) considered the first movie ever, based on the zoetrope and praxinoscope animations, or as well with the wonderful works of Étienne-Jules Marey on cinematic movement of different animals including man.

The Horse in Motion by Eadweard Muybridge show a sequential series of six to twelve "automatic electro-photographs" depicting the movement of a horse (1878).

Nearby Caixa Forum, crossing the great avenue just 500m away at Museo Nacional del Prado, can be found a major painting of Diego Velazquez, “Filipe IV, by horse” (1635), in which the horse's legs are represented with a sequence of faded frames alluding to motion in space-time, on that two-dimensional representation. Leonardo da Vinci on a commissioned project for an equestrian monument (1482) also produced a series of study sketches (1488-90) with a cinematic like representation of a horse, trough overlapping layers.

At Caixa Forum’s staircases not a simple person multiplies in mirror reflections while ascending or descending, as in the magnific Loos Haus staircases in Vienna (also completed in 1912 like the described Duchamp’s painting), but rather the stairs and surrounding walls de-composing materially in space (with multiple folds and angles) as well perceptually in the promenade’s time with a changing game between tangible matter (steps, and steel walls bent into triangles) and the given illusion by reflection of lights, shadows, and color nuances, while as/descending that staircase.

-

Text and photos of the staircase © Pedro Gabriel