FOMA 8: Built Projects That Inspired

Many music genres have been associated with a place, either a city or a region, like trip-hop with Bristol, techno with Detroit, fado with Lisbon, hippie with San Francisco Bay, but fewer have to specific built projects. Our eighth FOMA edition curated by Fani Kostourou, looks at five urban housing cases, which despite being architecturally overlooked, they are worth being celebrated for the development and enhancement of a musical heritage.

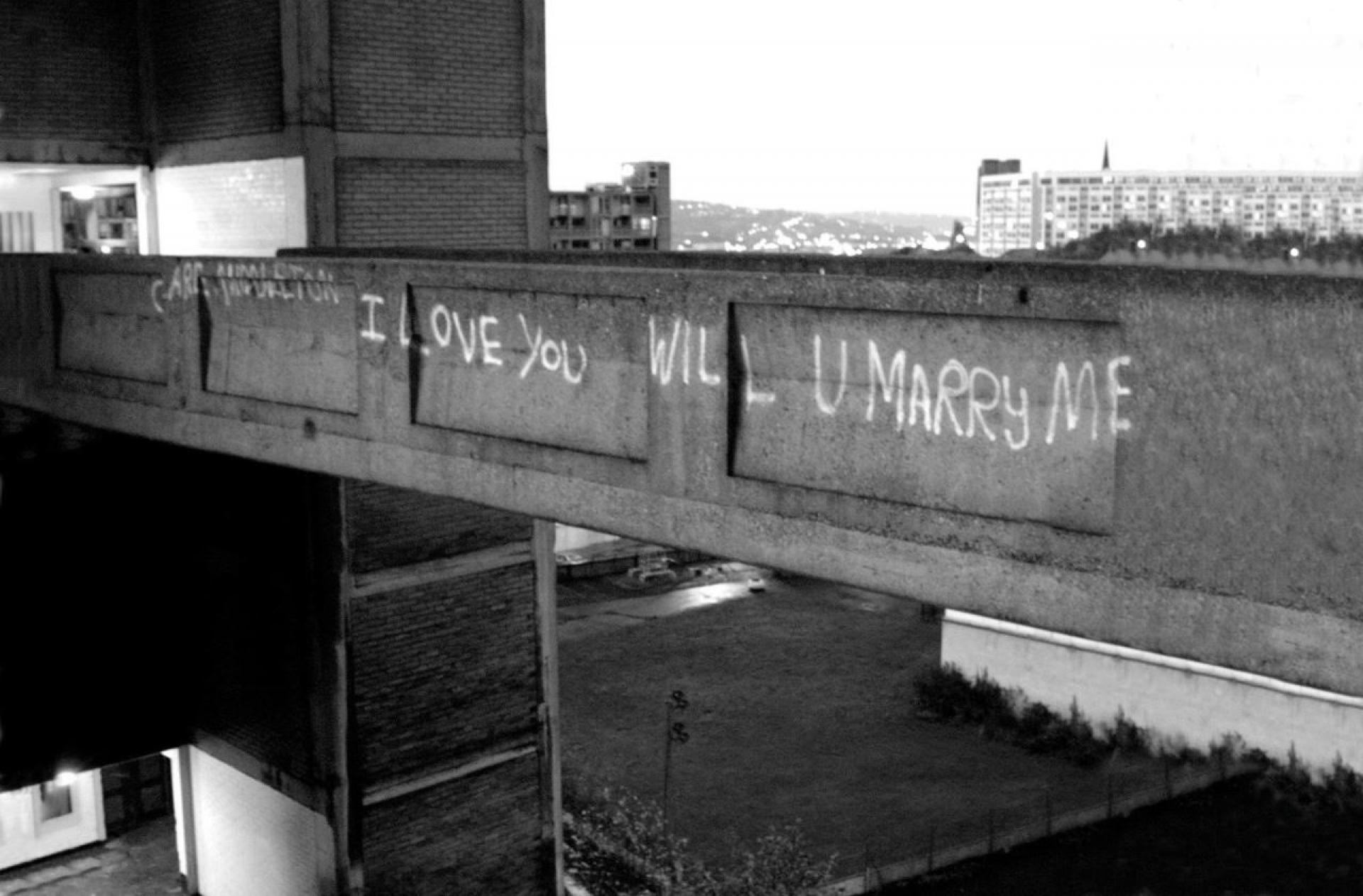

A housing estate of mind; iconic graffiti of Park Hill estate in Sheffield (2001).

They are not necessarily remarkable in their architecture or everyday reality; nevertheless, each of them has inspired and nurtured the emergence of a music genre. I argue that their architectural and urban design influenced the relationship of the musicians with the neighborhood, the city and the society, pushing them to discover new ways to react, challenge the norms and express themselves. My objective is to demonstrate a tacit connection between the tangible and intangible aspects of our built heritage.

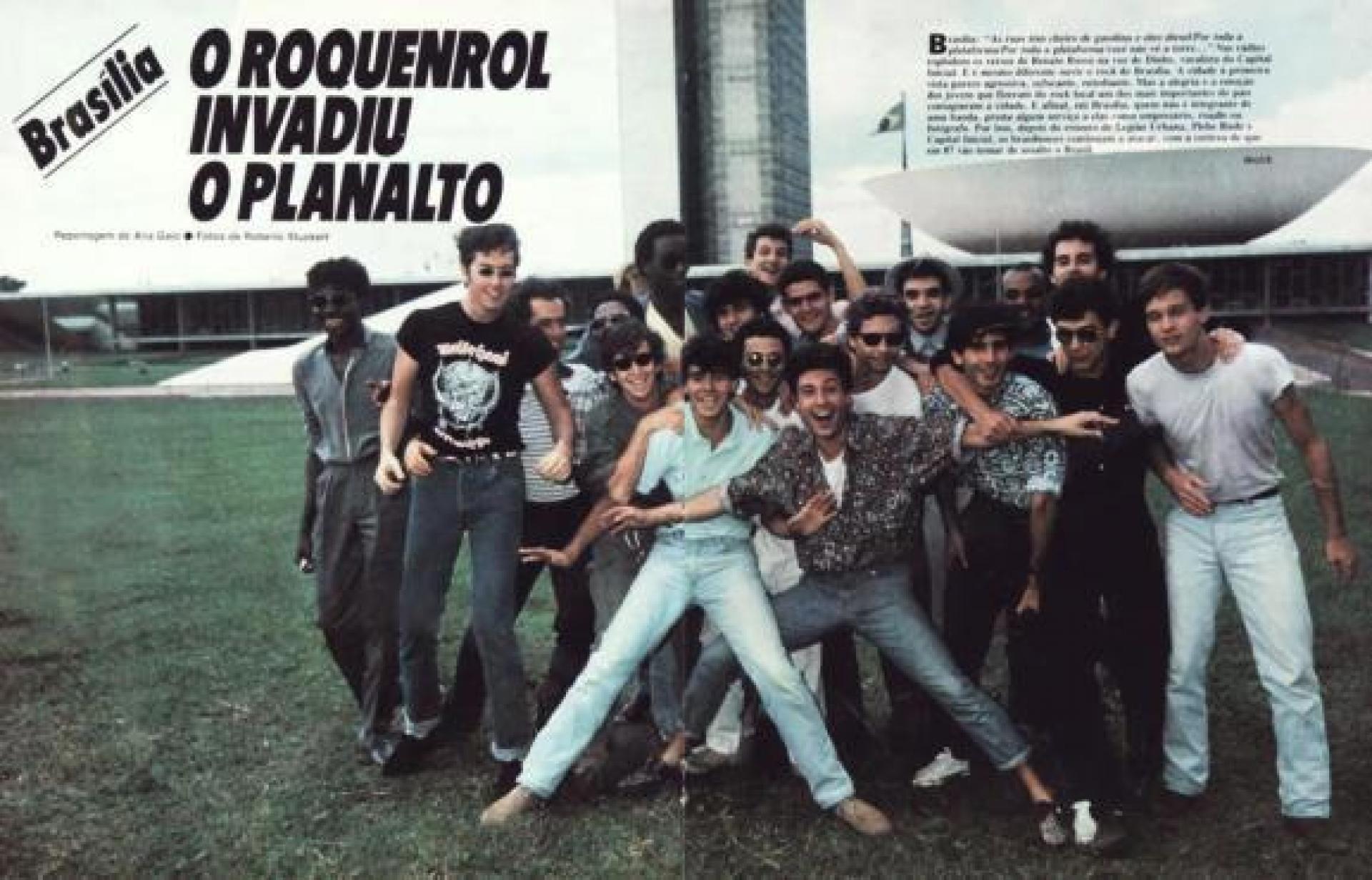

Third show of Aborto Elétrico in Brasilia. | Source via Enrockada

Such connection can be found between Colina Velha Building and Brazilian punk rock music. Colina is a housing complex at the University of Brasilia designed by João de Gama Filguéiras Lima in 1962. It is a massive concrete building characterized by the sophisticated use of prefabricated elements [1]. Between the 1970s and 1980s, its spacious apartments accommodated meetings of Turma da Colina, a movement of young Brazilian bands like Aborto Elétrico, which revolutionized Brazilian punk rock.

The social and spatial aspects of the life in Brasilia – the utopic, elegant, but monumental and monotonous city where the band members hailed from – and the state of Brazil after the end of the military dictatorship, strongly influenced the movement and the themes of the songs. These ranged from melancholic, political, and socially polemic subjects about drugs, war, nuclear plants, the state, military, and police, to topics of love, family and soul.

The story was that Aborto Elétrico stopped rehearsing at Colina soon after their first show, marking the beginning of the end for the Turma da Colina movement. Nevertheless, their legacy lived on through the subsequently formed and very successful bands, Legião Urbana and Capital Inicial. Colina building first provided shelter for a youth that was struggling to express itself within the cold vast urban setting of the federal capital. The disentanglement and alienation constituted a common theme in both the music and the architecture.

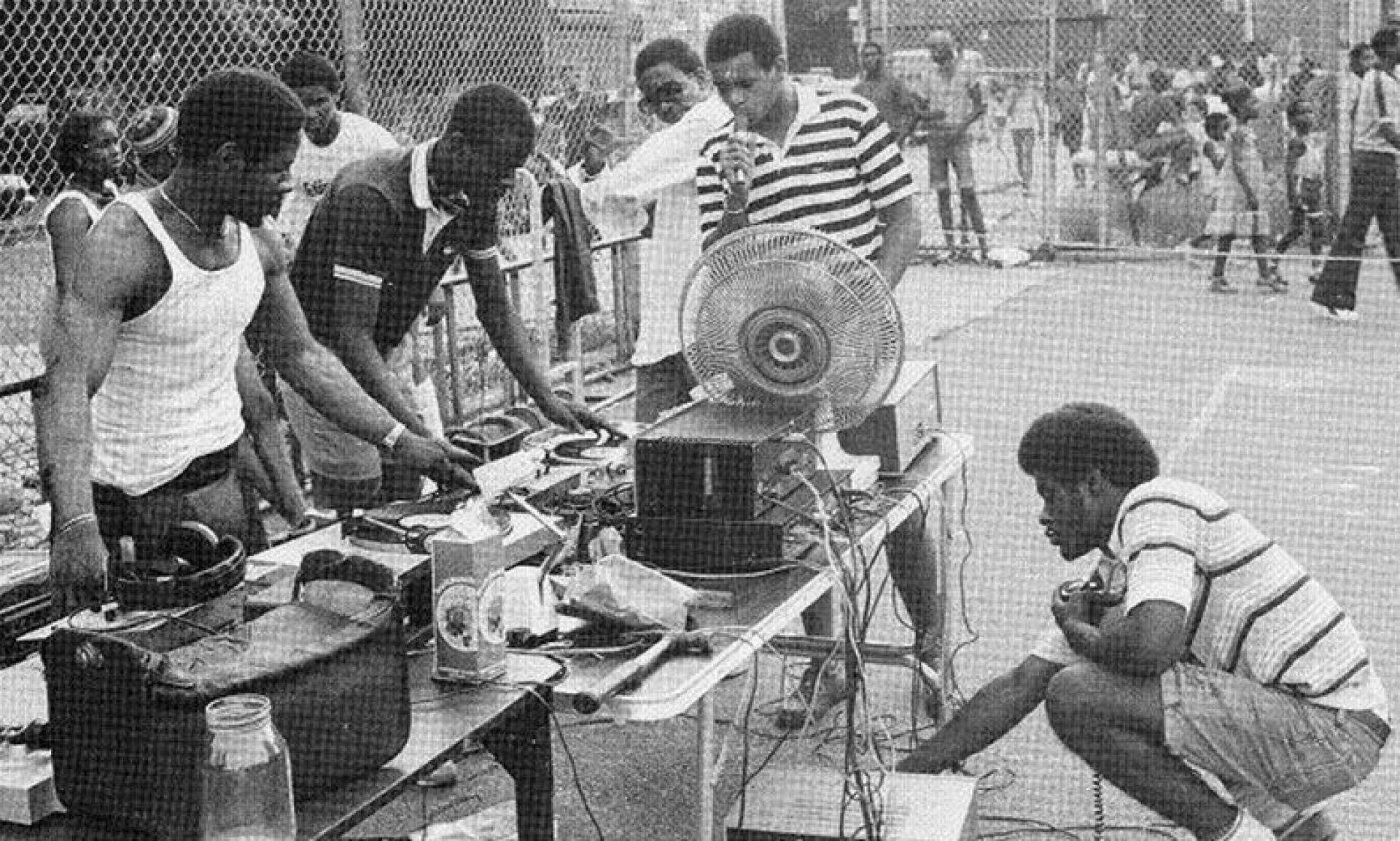

At the same time punk rock was being born in Brasilia, hip-hop culture was incubated under the roof of the 1520 Sedgwick Avenue in South Bronx, New York. The building has been officially recognized as the birthplace of hip-hop. Jamaican American resident Clive Campbell–aka DJ Kool Herc was the first to introduce hip-hop music. In the early 1970s, Herc and his sister started hosting house parties in Sedgwick’s recreation room. At the time, Bronx was struggling with street gangs, disco’s popularity was fading, and the radio was searching for a new audience [2]. This is why block parties quickly turned into popular gigs, and moved out to public spaces. For the local young minorities, hip-hop was an alternative to the violent gang culture, a way to be heard expend their pent-up energy and a chance to generate income.

DJ Kool Herc sets up for the legendary block party at 1520 Sedgwick Avenue, Bronx, NY. 11th August 1973 | Source via Urban Ubiquity

In the book How to Rap Immortal Technique explains the role of parties in old school hip-hop: “Hip-hop was born in an era of social turmoil and real economically miserable conditions for the black and Latino people [..] in the same way that slaves used to sing songs on a plantation”. While at the beginning songs were about party related subjects, slowly the lyrical focus shifted on social issues, like life difficulties in decayed housing projects, so that hip-hop became, in the words of T.I. rapper: “a reflection of the environment that the artist had to endure before he made it to where he was. [..] if you want to change the content of the music, change the environment of the artist”.

After a lengthy period of neglect and shady dealings, the building was finally saved from the real estate market, the new owners sought to work with the tenants to renovate it and safeguard its importance. This was the result of a collective effort by locals including Herc, groups like the Tenants and Neighbors Association, and politicians like Senator Schumer. So that the 1520 Sedgwick, “an otherwise unremarkable high-rise just north of the Cross Bronx Expressway and hard along the Major Deegan Expressway” was not only “the Bethlehem of Hip-Hop culture”, but also “the emblem of New York’s affordable housing crisis”.

Scene from La Haine film by Mathieu Kassovitz in the Cité de La Noé in Chanteloup-les-Vignes, France (1995) | Source via Film Grab

Nearly ten years after the birth of hip-hop in Bronx, rap arrived in France, demonstrating a different lyrical content concerned with issues of racism, integration, diaspora and ethnic diversity. The social and political situation of the early 1980s nurtured the establishment of a music culture that got enthusiastically embraced by the marginalized young minorities of a disturbed postcolonial French society. Key moment for its rise in popularity was the film La Haine by Mathieu Kassovitz in the mid 1990s where rap associated itself with the identity of young immigrants in the Parisian banlieues [3], further linking hip-hop to spatial concepts like ghetto and mass housing.

One of these post-war mass housing projects was the cité du Val-Fourré, an ideal neighborhood for workers of the automobile industry in Mantes-la-Jolie. In the west periphery of Paris this neighborhood offered nothing but housing, leading to a mono functional and segregated area, devoid of any real urban stimuli, that soon became a notorious ghetto of marginalization, poverty, violence, drug dealing, and street gang rivalry.

The situation motivated young immigrants to become involved in rap music as a way to express their anger and attract attention; a desire to be heard and taken seriously. French rapper Mokobe asserted: "We were rebels. We made music to speak about our daily lives, about people like us, and to defend their cause.” At the same time, songs reflected a strong sense of belonging to the working class cités and their brotherhood.

The media attention Val-Fourré attracted had it included in a mega redevelopment programme in 2003 run by the Agence Nationale de Renovation Urbaine (Anru), which enhanced local activities and services. Land use diversity, however, may not ensure social mixing and integration, as the IAM band sang in 1997, “the elected officials carry out refurbishment to reassure, but it’s always the same shit, behind the last layer of painting”.

Same applies to the Crossways Estate, another post war marginalized residential project in East London, now rebranded as Bow Cross area. Thirty years after Herc’s parties, East London gave birth to a different music genre. What was South Bronx to hip-hop, was East London to grime, particularly the Crossways estate in the Bow area of Tower Hamlets borough. Wiley “the godfather of grime” affirms, the music genre comes all from Bow.

British rappers Dizzee Rascal and Wiley relax by the Crossways estate in Bethnal Green, London (2002) | Photo © avid Tonge/Getty Images

Grime is a hybrid of garage, drum and bass, hip-hop, and dance music characterized by machine-like, media and city sounds [4]. Dan Hancox argues there is a certain brutalist quality to grime as a genre: “Like the architecture, it’s very stripped down”. Urban at its very core, grime’s commentary is preoccupied with two subjects: the contemporary grim lives of the young, black, male MCs in the impoverished London council estates, and the sound of the future city that they always dreamed of– when looking at the nearby Canary Wharf. Their lyrics are playful, hedonistic, at times affectionate and aggressive, nostalgic and rebellious, yet dark and violent. For they describe what young sought to reclaim, their right to a city that was ignoring them. “Coming from where I come from, you didn’t feel a part of London,” Dizzee told to the BBC London.

Grime also emerged at a time that governmental policies initiated the demolition/refurbishment of council estates to regenerate some of UK’s most vulnerable areas like Bow. Crossways was in poor condition, half-abandoned, occupied by homeless people, unpopular with residents and vulnerable to antisocial behaviors. Recent refurbishment, though, forced out the former “working-class Londoners who might listen to, or indeed make grime”.

This may not be the future of the 3000 Viviendas project, an area built between 1976-77 in the southern periphery of Seville, to rehouse low-income people from post-disaster areas, precarious settlements, other urban quarters and the countryside [5], the majority of which were gypsies.

The 3000 Viviendas project is centrally located in Poligono Sur, which gets geographically and socially isolated due to surrounding motorways and railway lines that act as physical boundaries. The spatial segregation combined with the social uniformity and a lack of public services and other infrastructure led the project into decay and extensive informalization. Issues of drugs, illiteracy, unemployment, delinquency, and functional and physical deterioration of the built environment came along, giving it the name of vertical shantytown.

It was this area that got associated with the origins of new flamenco in the 1970s ought to young and talented gitanos expelled from Triana in the late 1960s; notably the Amador brothers and their group Pata Negra. The group revived the traditional flamenco [6] by fusing it with elements of rock and blues, creating the art of blueslería. Similar to the traditional one, new flamenco was influenced by the hybrid identity and culture of Romani people [7]. For the residents of 3000 Viviendas, the music was not only a means to express their everyday life and feelings, but also a mechanism to reverse the downhill of degradation, give visibility to and breathe new life into the neighborhood. The songs’ lyrics often revolved around topics of diaspora, displacement and marginalization as well as passion and affection for the neighborhood.

This affection is best depicted through the example of Alala documentary. The movie shows how flamenco is used to educate and inspire young locals, allowing them to envision a better future for their neighborhood. Here, music empowers the community to stay and feel for the area, generate opportunities and transform itself and its space through a bottom-up process.

-

[1] Czajkowski, J. in Emanuel (ed) (2016) “Contemporary Architects” p. 250

[2] Toop, D. (2000) “Rap Attack 3: African Rap to Global Hip Hop”. London: Serpent’s Tail.

[3] Higbee, W. (2007) “Mathieu Kassovitz”. Manchester University Press.

[4] De Jong, A. Schuilenburg, M.(2006) Mediapolis: Popular Culture and the City.

[5] Torres Gutiérrez, F. J. (2011) “El territorio de los desheredados. Asentamientos chabolistas y experiencias recientes de erradicación en Sevilla”. Hábitat y Sociedad (3), pp. 67- 90.

[6] On November 16, 2010, UNESCO declared flamenco one of the Masterpieces of the Oral and Intangible Heritage of Humanity.

[7] Hayes, M. H. (2009) “Flamenco: Conflicting Histories of the Dance”. McFarland Books. pp. 31–37.

Fani Kostourou is an architect and urban designer. She studied architecture at the National Technical University of Athens (NTUA), and holds a MAS in Urban Design from ETH Zürich and an MRes in Spatial Design: Architecture and Cities from The Bartlett, UCL London. Fani’s design work has featured in publications such as Minha Casa, Nossa Cidade: Innovating Mass Housing for Social Change in Brazil (Ruby Press, 2014) and group exhibitions at the Museum of Modern Art in New York (2014-15), Columbia GSAPP’s Studio-X in Rio (2013), Museu de Arte do Rio (2014), X São Paulo Biennale (2013) and 15th Venice Architecture Biennale (2016) among others. Fani is currently an EPSRC-funded doctoral student at The Bartlett School of Architecture, Fellow of the Higher Education Academy (UK), and Postgraduate Teaching Assistant at The Bartlett School of Architecture, and Development Planning Unit, UCL. Recently and as part of her studio teaching, she has co-edited two publications on Emerging Design Research (The Bartlett 2015, 2017). Her activities also include project consultancy, graphic design, writing and editing. In April 2017, Fani joined the MIT Department of Architecture and Computation as a visiting PhD researcher.