Gabu Heindl: No To The Discriminatory Architecture

We are leaving the 2023 with the last Weltraum in this season. On the Independent Coastal Radio NOR we hosted Gabu Heindl, whose architecture says yes and no. Yes to the design of public buildings and infrastructures, cultural and educational buildings. No to chauvinistic, racist or discriminatory architecture, to exploitative project proposals, suburbanizing single-family houses or speculative buildings. All projects are positioned in the urban cultural environment from film, art, theater and music to kindergarten, school building and social housing.

Gabu Heindl | Photo © Katharina Gossow

What relationships in space create chauvinistic, racist or discriminatory architecture?

Gabu Heindl: I've written this statement on my website and it's been a bold statement to remind myself trying to see how architects can be less complicit in chauvinist building of our environment in supporting racist housing politics, in engaging in discriminatory or defensive urban space design. It is something that should assure us that we can actually as architects ask ourselves to what extents we can contribute to a less racist, to a less chauvinist, to a less discriminatory world.

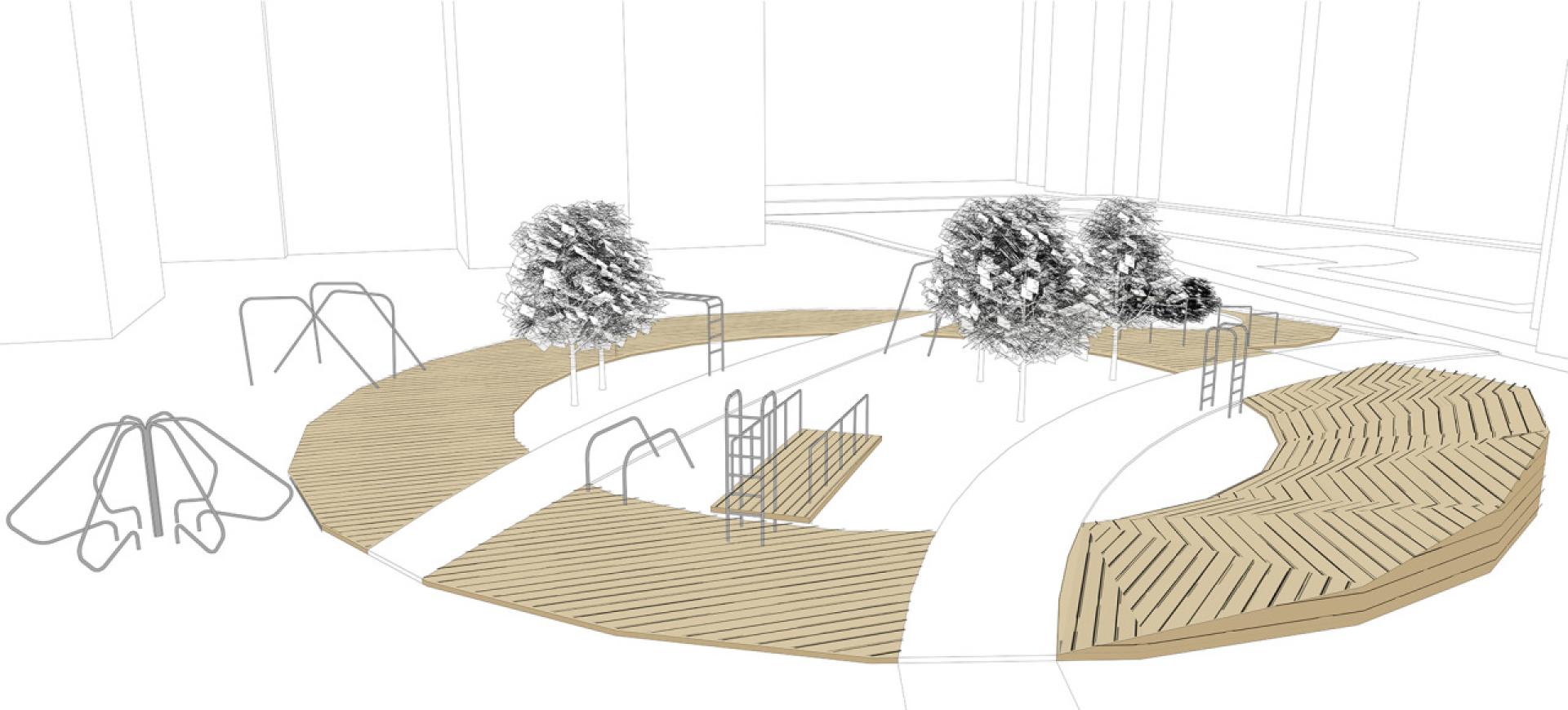

Extension of the self-organized housing project Planet 10

Which approach you follow in creating and defining your projects?

GH: I wish there was one path or one way of working. It seems every task, every project somehow asks for its own project development. But I do believe that thinking about project development affects what we do and how we could in the best sense accommodate the engagement of those whom we work with. I hope that we rarely consider it as working for but rather working with; hence we take sides for those who will use the space but not always is the client.

Extension of the Kindergarten Rohrendorf near Krems (2008). | Photo © Lisa Rastl

If you design a school or a kindergarten the client may be sitting in some office in Vienna organising school buildings. It's the kinds and the teachers who we actually have to speak to. And when it comes to self-initiated housing, which my office is more and more engaged in: affordable, non-market and co-housing, that specially requires a different approach. We are not taking a brief and just turning it into architecture, but we are developing the brief with people.

How living in New York changed your perception of the city?

GH: Of the general city maybe more than of New York I would say. I lived in Tokyo and in New York, which were the largest cities that I lived in, and then I lived in Amsterdam for some time. All of that was really not important to me because it was so to say my lifestyle ideal of being in the biggest cities, it was much more an idea to move to places to understand how it is to live there. I also had experienced life in a small village. Since some time now I am based back to Vienna. As I am now commuting between Kassel and Vienna I can say it all supported to understand this one idea: if a city allows you to live well when it comes to affordable housing, public space, schooling, healthcare etc. this gives you freedom to be independent, freedom to choose what you want to work on. This is what I found really until today the best to experience in Vienna.

Gabu Heindl in discussion with Boštjan Bugarič

What about Vienna?

GH: I have the possibility to join the activism of some of my friends in Vienna who are fighting racist exclusion of social housing and the discriminatory Viennese first policy. There are still welfare structures existing in the city and still to a lot of people, yet we are fighting for that they apply for everyone: having your basic needs not to become your existential worry. is important for everybody. everyone should be able to chose what they want to engage with, what and who to work together. Of course also for an architect, it makes it easier for me to not engage in work I wouldn't want to do just for the sake of earning money.

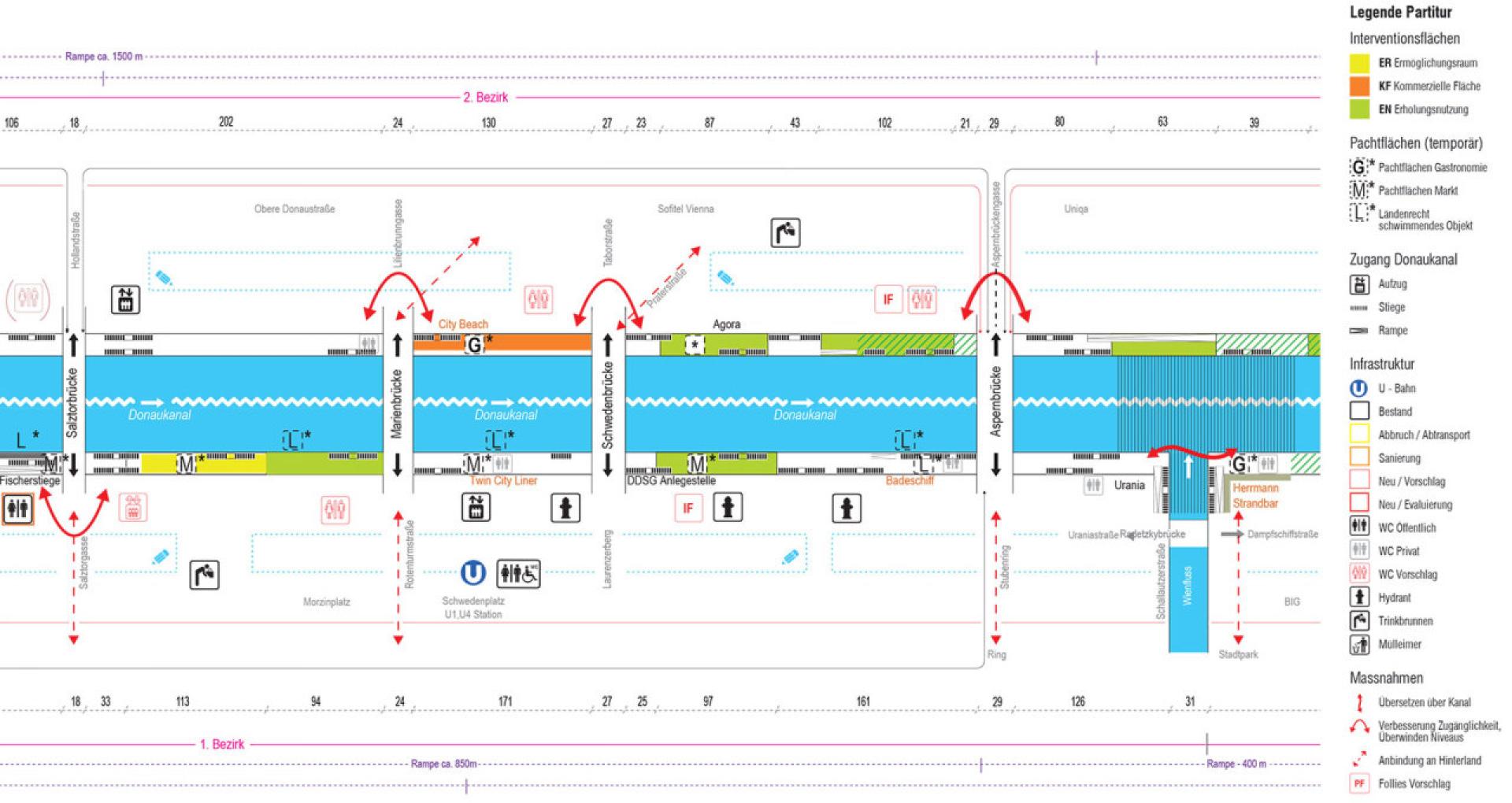

Donalkanal Partitur, the regulation and development guidelines for the Viennese Donaukanal In cooperation with Susan Kraupp (2012 – 2014). | Photo © Gabu Heindl

Yes, I think that's more difficult in New York, to come back to your question, but then of course also too many people in Vienna are still exactly in this situation that they don’t know how to pay rent or pay food at the same time at the end of the month. That is really what drives me, to fight for these basic rights of everyone.

What about the rest of the Europe, can you see the indirect discrimination?

GH: For sure, there is discrimination, still East-West, South-North, but also within cities. Every city that we are working in, in every city that we are critically mapping we can identify areas that have less infrastructure, that are less equipped, and at the same time it doesn't even mean necessarily that they are more affordable. That's the absolute tricky part, that exploitation comes along the exploitation within just the simple need of housing. Affordability does not relate to the quality of space. Yes, we need to speak about the rights to decent housing and a decent life for all the people in Europe – for everyone who is here and including people who will want or need to migrate to Europe in the future.

The Promises of Modernist Premises: Pool Trakiya is a collective re-appropriation of a deserted pool as communal outdoor centre in Plovdiv, Bulgaria (2016).

To combine the social question together with the ecological question means at the end of the day that there will be some new distribution and that also means that if we speak just about distribution of space some will have to actually to give up of which they have too much at the moment. That is the hard message that nobody wants to talk about. If we speak about living with less CO2 emissions, sharing more space then the crucial question is who exactly do we address? And we shall certainly not address those who already live on so much smaller space and means than others.

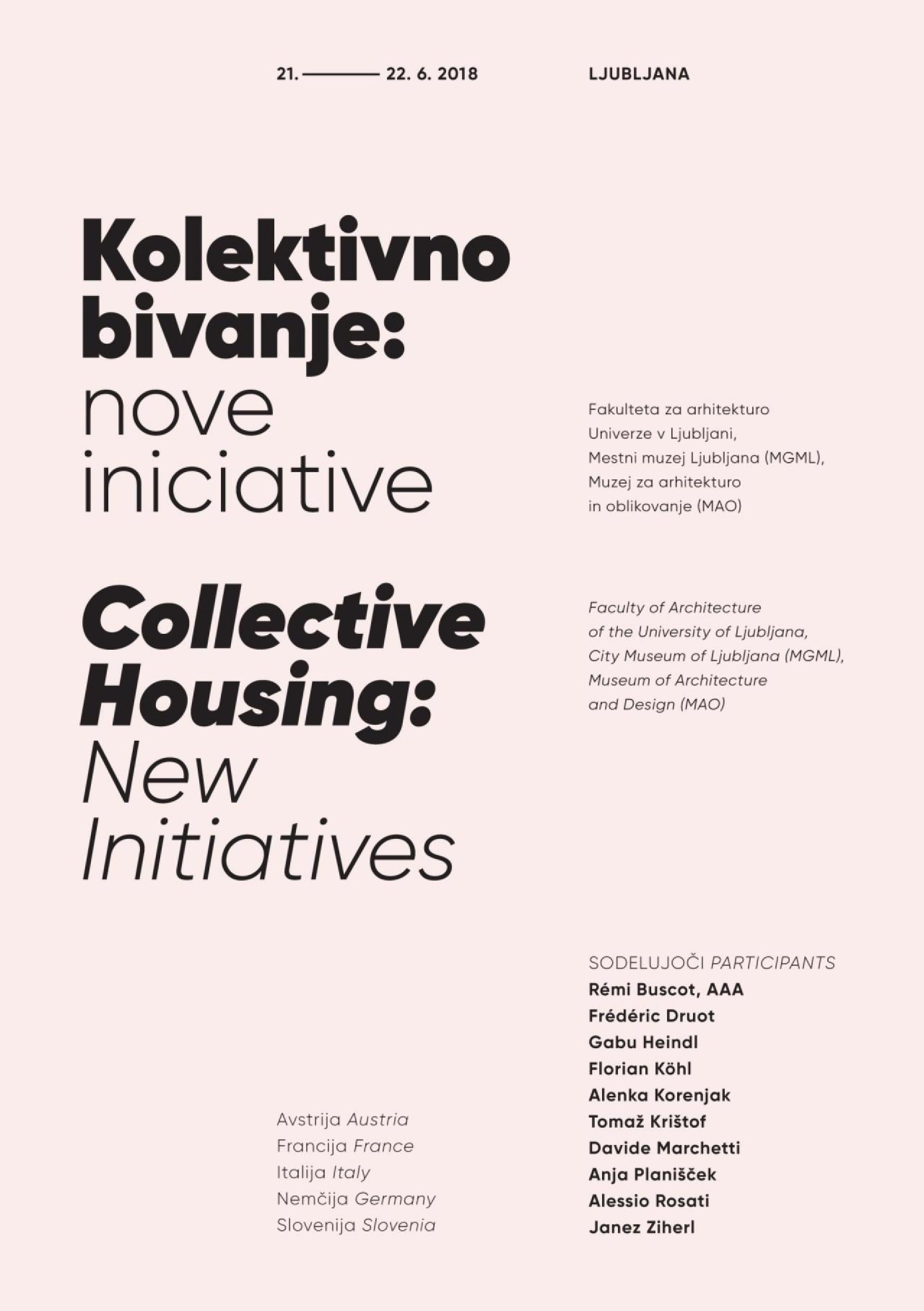

Architectuul organised a conference about social housing in Ljubljana, Slovenia in 2018 with Gabu Heindl, Frédéric Druot, Rémi Buscot (Atelier d'architecture autogérée), Florian Köhl, Davide Marchetti, Alessio Rosati, Alenka Korenjak, Anja Planišček.

In 2018 we had the opportunity to host you at the conference Collective Housing: New Initiatives in Ljubljana to share different knowledge of cooperative housing, knowledge that is lost because of being shame of ideas coming from Yugoslavia; what projects from Vienna did you present to be useful in Slovenia?

GH: I think every place itself has a history of common ownership model and I think what we are planning at this moment with my dear University colleagues such as Iva Marčetić at the Master Studio in Kassel is to really look into different common ownership models in different histories of different places. It's not about bringing a Viennese model to some other places or a successful cooperative logic that is established somewhere to be imported somewhere else but in a way all the cities can relate to a common other history or maybe sometimes supposedly lost history or an alternative history that they could actually revive. I am interested in what logics of common ownership and common ways of organising, also governance, or questions of how to produce together have existed in a specific place. And there I would say, we should much rather share maybe the histories of reviving, of maybe sharing experiences of how some of this knowledge has been lost but how it also can be recuperated, further re-invented, critically inherited.

From the solo exhibition Urban Conflicts - A Housing Manifesto (2022). | Photo © Jan Prokopius

I studied the case of Red Vienna, which is a case of communal ownership housing models and with a supposedly successful continuity, and even there I did find alternatives in this already alternative history. If we consider Red Vienna to be an alternative case to so many cities of neoliberal housing development then even parallel to this public housing story you could find even more emancipatory, more feminist, more community-organization than top down housing provision. I am very happy that as an architect I can support activists and groups to self-initiate projects that have another solidarity idea than purely provision of standardised housing. I consider our work nearly as a reviewing of some of the historic emancipatory notions. If the groups I work with do so or not, doesn't matter. But we can see such a powerful agonistic drive in so many cities, especially if you think of the politics of all these powerful movements in Belgrade, Zagreb and so many cities in Southern Eastern Europe. Then I think there is a lot to learn for people in Vienna the other way around.

This question of mine was more a provocation.

GH: It really was. ☺

How do you see the work of women in architecture?

GH: I am really sad this still has to be a topic, and I am very grateful that a lot of my colleagues are actually working on this ever actual topic. I've seen my feminist engagement in architecture in looking into the very structural inequality not so much of architects but generally the structural spatial injustice between men and women and even more intersectionally with regards to class and race next to gender. I would try to always think these categories together. We need to look at what is happening in terms of accessibility to space, in terms of literally the possibility or rather impossibility to partake in anything, starting with being able to live peacefully, also affordably but also to take part in public space, to partake in the making of our cities, if we relate that to Henri Lefebvre for instance.

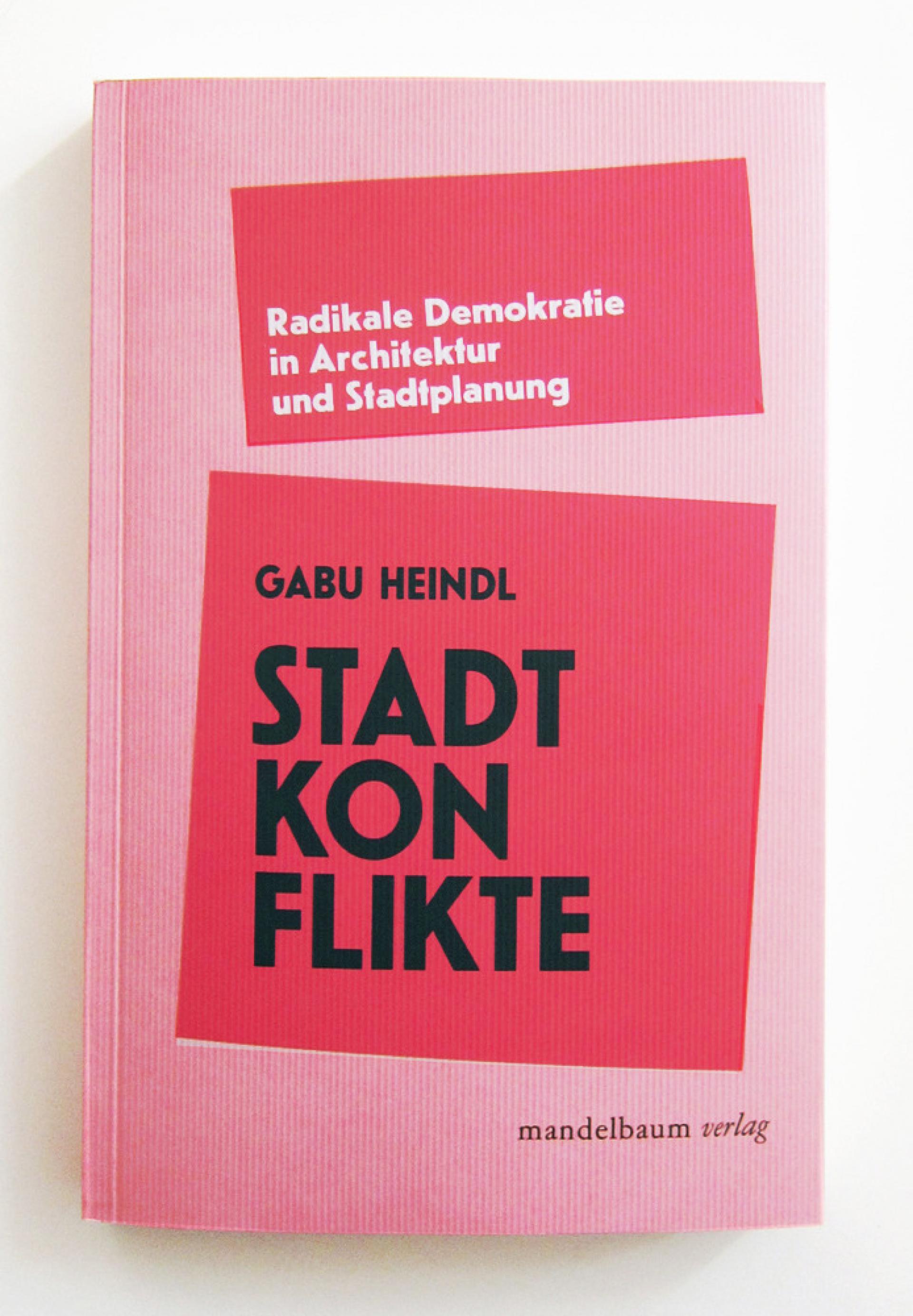

Radical Democracy in Architecture and Urban Planning by Gabu Heindl

In Kassel we are currently working on a project where we look into the interrelationship between the gender wealth gap and home ownership or freehold flats. The gender wealth gap is even wider than the gender pay cap. Looking at the trend or rather the political project of buying a home shows exactly how the structural inequality between men and women gets ever bigger. With little chance for wealth acquisition some people will never be able to afford to buy a house or an apartment. However, what we want to do is not to argue for every women to become as wealthy as some men but rather radically critique the idea of wealth and the constructed goal of owning an apartment and further look into common ownership housing, or “social property” and this comes again back to rental housing. We would like to develop good arguments against the idea of owning a home. With owning I mean to have a property title of it, but of course what we need to do is to have the idea of “owning” as belonging, in terms of that an apartment, a home is mine, I have the key, I have security, I will be able to live there and will not be thrown out, also that the rental price will not grow erratically. So in this sense we need to gain precision between the terms property and ownership and also the belonging to a place and all the security which should come with that.

Outside in Prison is an art project in a men’s prison courtyard in Krems (2011). | Photo © Gabu Heindl

We are highly inspired by Silvia Federici, who in the 1970s with a whole group of feminists were supporting the battle for wages for housework. But turned the battle even further and declared the slogan of wages against housework, said something like "we don't want just to be payed for house work, we want to change the logics of who is doing what sort of work and how we share it completely differently." Again I think the history of feminism has so much to offer for us, and how with their critical thinking we can do another turn and understand spaces within the logics of capitalism or also within the logics of white wealthy male.

How do you see yourself as an educator?

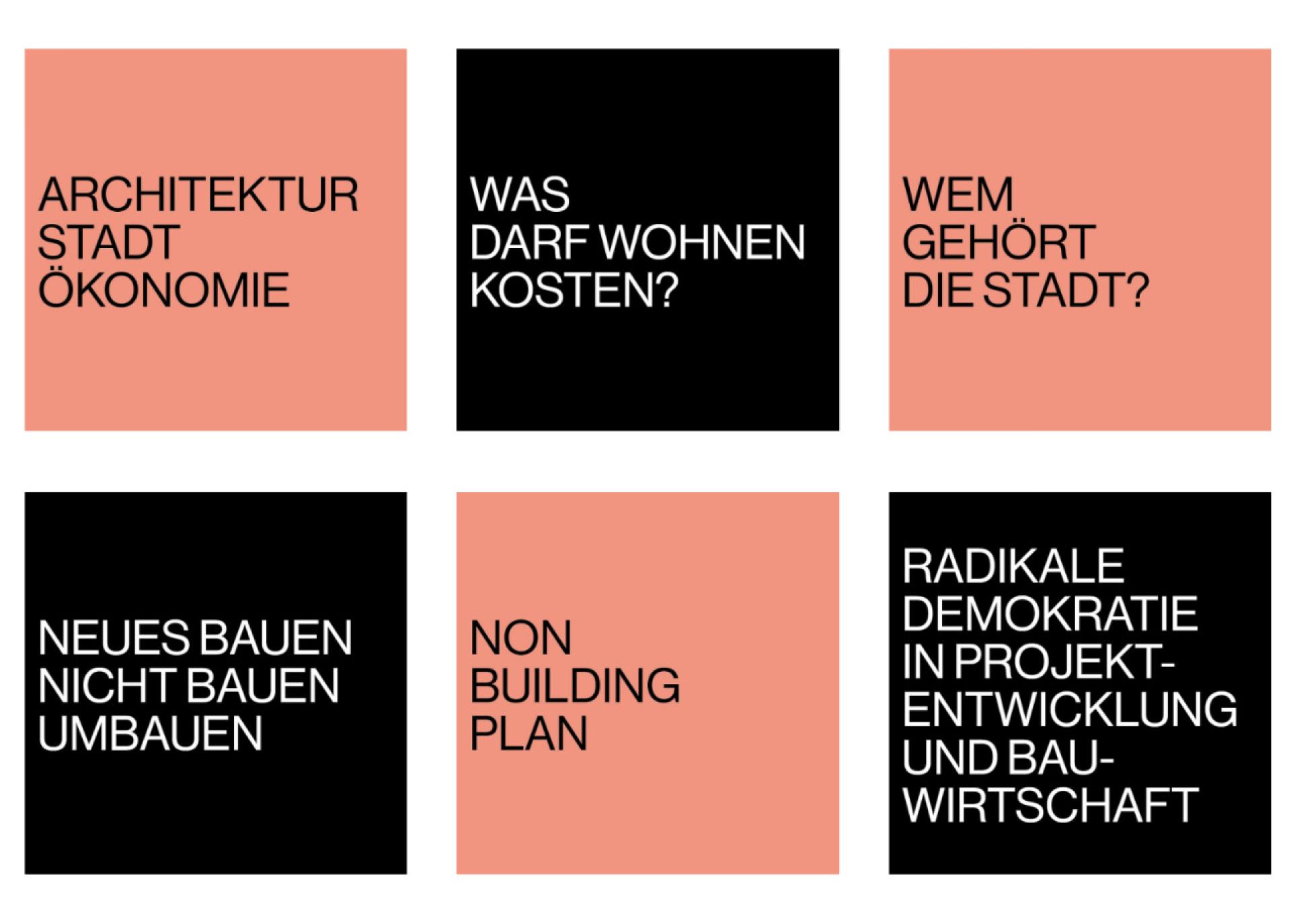

GH: The reason why I like to teach is because it is beautiful to see this young generation of students to be so political again. I can see how our generation has to keep up with the radicality that these kids are demanding and this is enormously empowering to see how some paradigm changes could really happen as well as systemic and radical rethinking. Our students literally demand demolition stop, they are demanding the stop of new construction as long as there is so much vacancy, as long as there is so much unused space. With this powerful force we are challenged to completely rethink what architecture is about. How can we engage in world without destroying so much, without using so much energy, without architecture being such a big part in emissions and all the waste production. When I took over the chair of ARCHITECTURE CITIES ECONOMIES | Building Economy and Project Development I realised that this is exactly where we need to be at this moment: to really redefine who and what project development does, how it could contribute to more justice, but also support solidarity and circular economies, the rebuilding instead of new sealing, concepts of using instead of owning.

Master Studio Urban Conflicts in Housing Development at the Department of Building Economics and Project Development: Architecture Cities Economies in Kassel, Germany.

And if we do construct newly then maximally social and ecological and that's already a big claim, which we need to define properly. Just as much as economies: I hope that students think about financial economy not more than of commoning, feminist or foundational economies. There are so many other concepts of economy which have to come to the foreground again. And since my department includes the term “project”, which is such a modernist driven concept, we need to rethink it and that applies of course also to the term “development”. How to conceptualize development without growth? At then, very simply at the end, who is a project developer? I would love to empower students, and also activist – as that's what I do in my architectural work – generally to make people understand that they can all be project developers. There is not only Benkos; quite the opposite. We have to democratize the idea of project development with regards to the housing crises and the overshadowing climate catastrophe. It is great that the University Kassel gives me a chance to do so, it is an important moment to engage and contribute to this change.

What about creativity?

GH: If I speak about this concept of building economy people think that architecture doesn't need any creativity anymore. I would really like to emphasize that to repair all our built environment and to make it a livable environment for everyone and every species, we have to use so much creativity and design so many beautiful things. We shouldn't worry that to work on a socio-ecological transformation wouldn´t need all of our creative energy, let's share it for a more caring and just world.

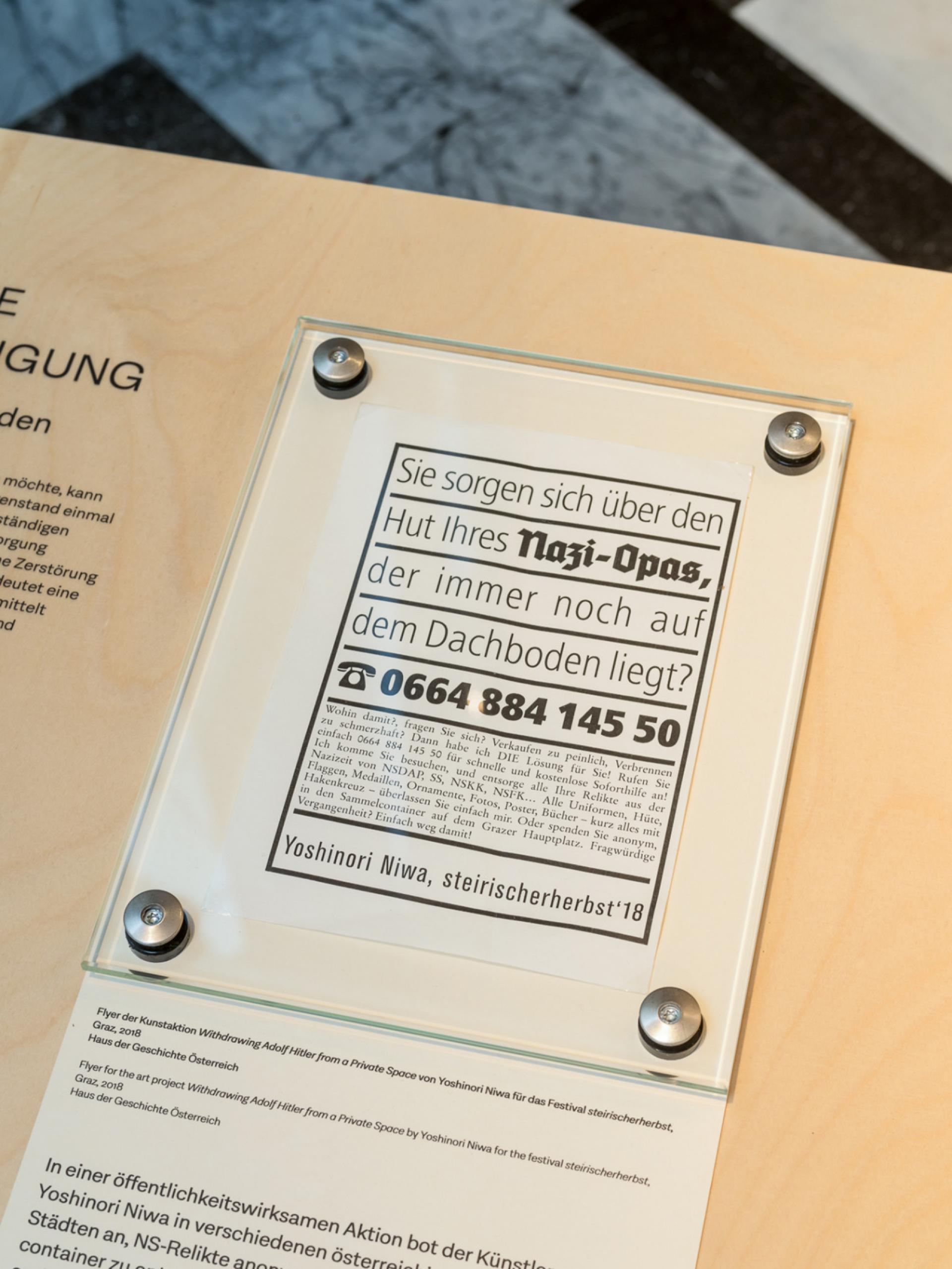

Disposing of Hitler: Out of the Cellar, Into the Museum. an exhibition at Austrian Museum of Contemporary History Vienna. | Photo © Klaus Pichler

Gabu Heindl is an architect, urban planner and activist in Vienna. As professor at the faculty of architecture she is heading the design and research department ARCHITECTURE CITIES ECONOMIES | Building Economy and Project Development at the University of Kassel. Her office GABU Heindl Architecture focuses on public space, public buildings, common-ownership and non-market housing as well as collaborations in the fields of history politics and critical artistic practice. From 2013 to 2017 she was chair of the ÖGFA – Austrian Society for Architecture. Gabu has obtained a doctorate in Vienna and studied architecture in Vienna, Tokyo and Princeton. From 2018 to 2021 she was Visiting Professor at Sheffield University with a research focus on Urban Commons and subsequently Professor of Urban Design at TH Nuremberg. 2019-2023 she was Unit Master at the Architectural Association School of Architecture (AA), London. Gabu lectures frequently and and has been publishing numerous articles and books including the co-editing of Building Critique, Architecture and its Discontents, Spector Books 2019 and the monograph Stadtkonflikte. Radikale Demokratie in Architektur und Stadtplanung, Mandelbaum 2020 (2022 3rd edition).

Here You can listen to the WELTRAUM interview.