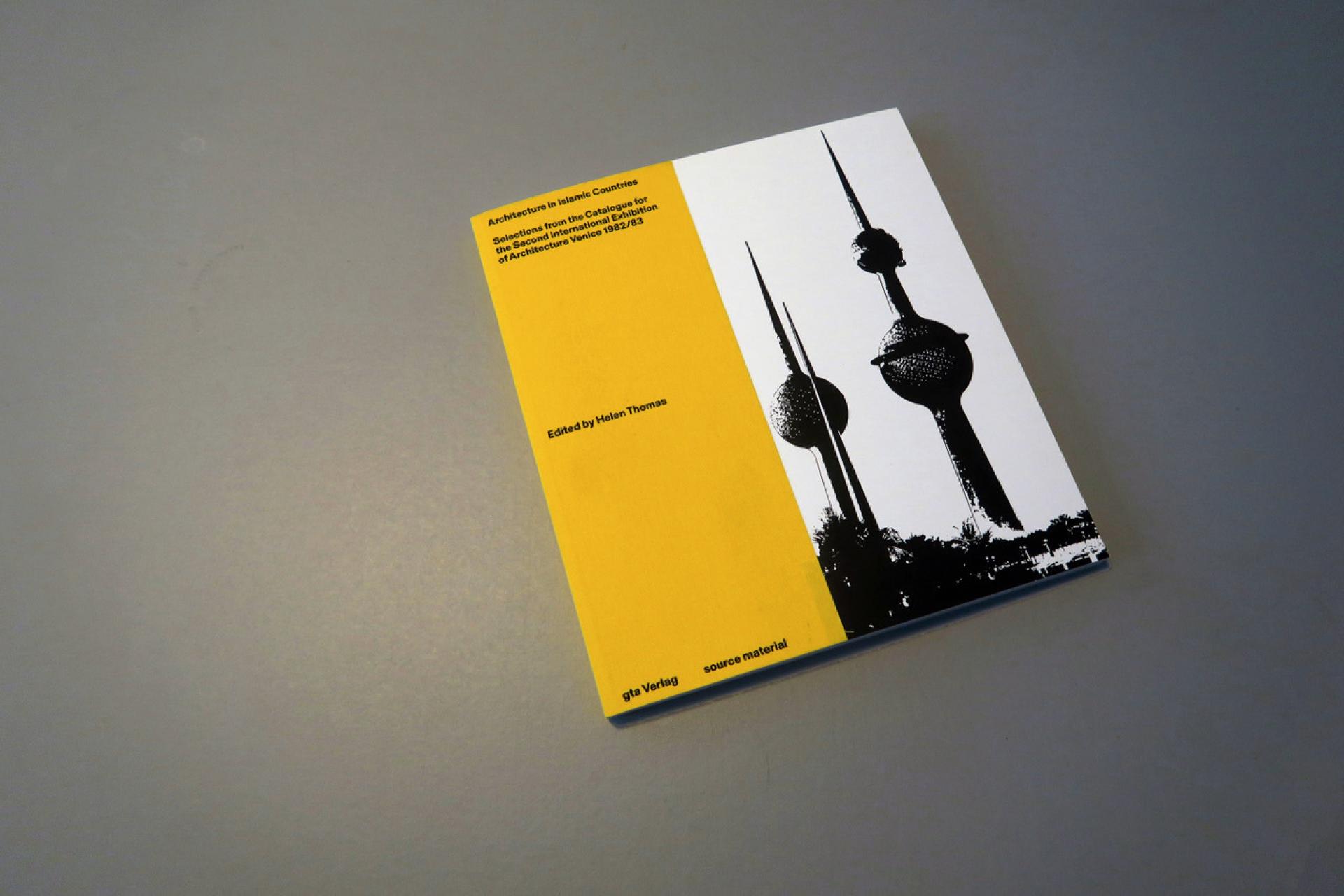

Helen Thomas: Architecture In Islamic Countries

Selections from the Catalogue for the Second International Exhibition of Architecture Venice 1982/83, edited by Helen Thomas.

If you are familiar with this website, you might remember an extensive survey of the Venice Biennale of Architecture - Cold Cases where no less than fourteen authors went back to the history of the institution and shared their experiences and actual thoughts.

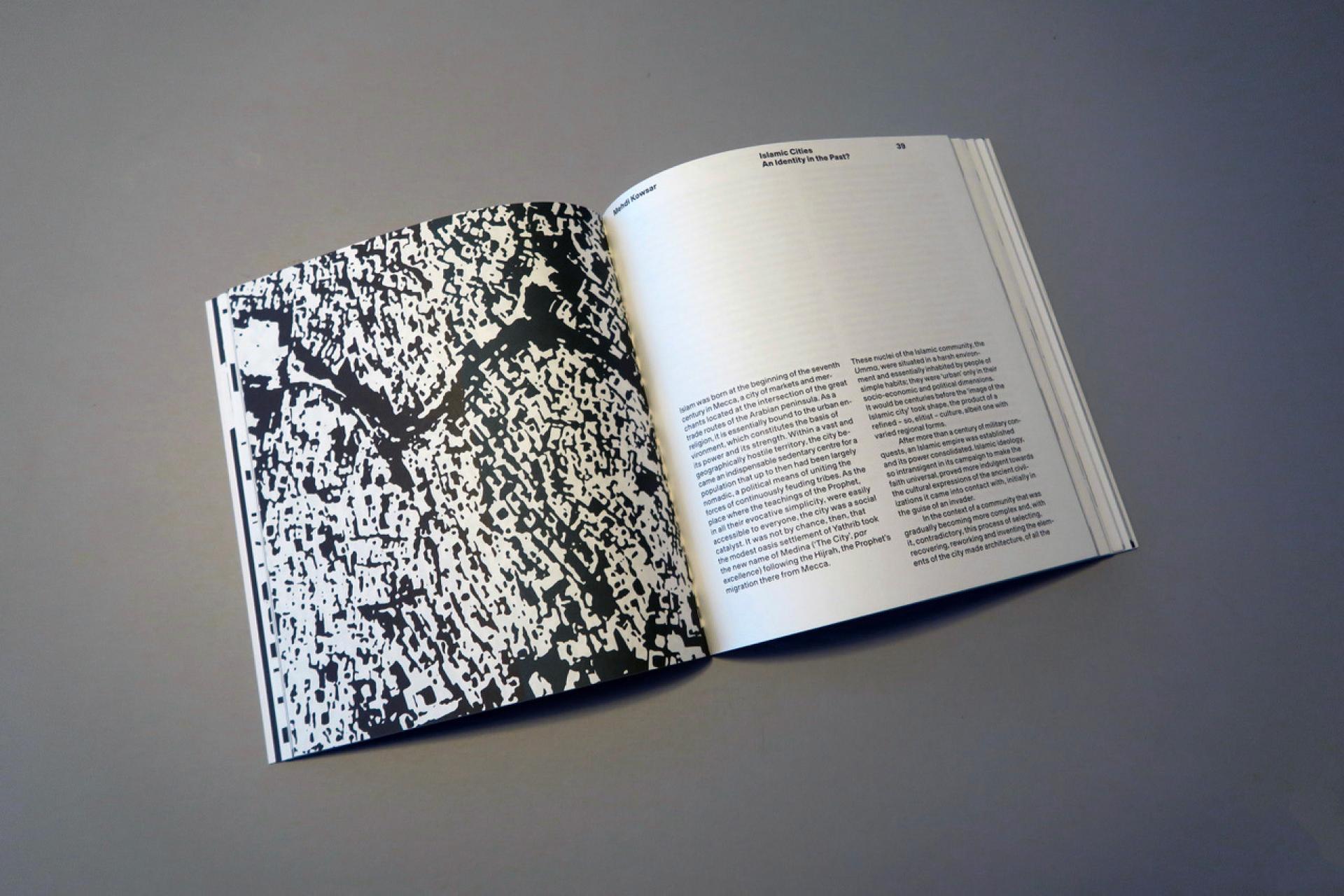

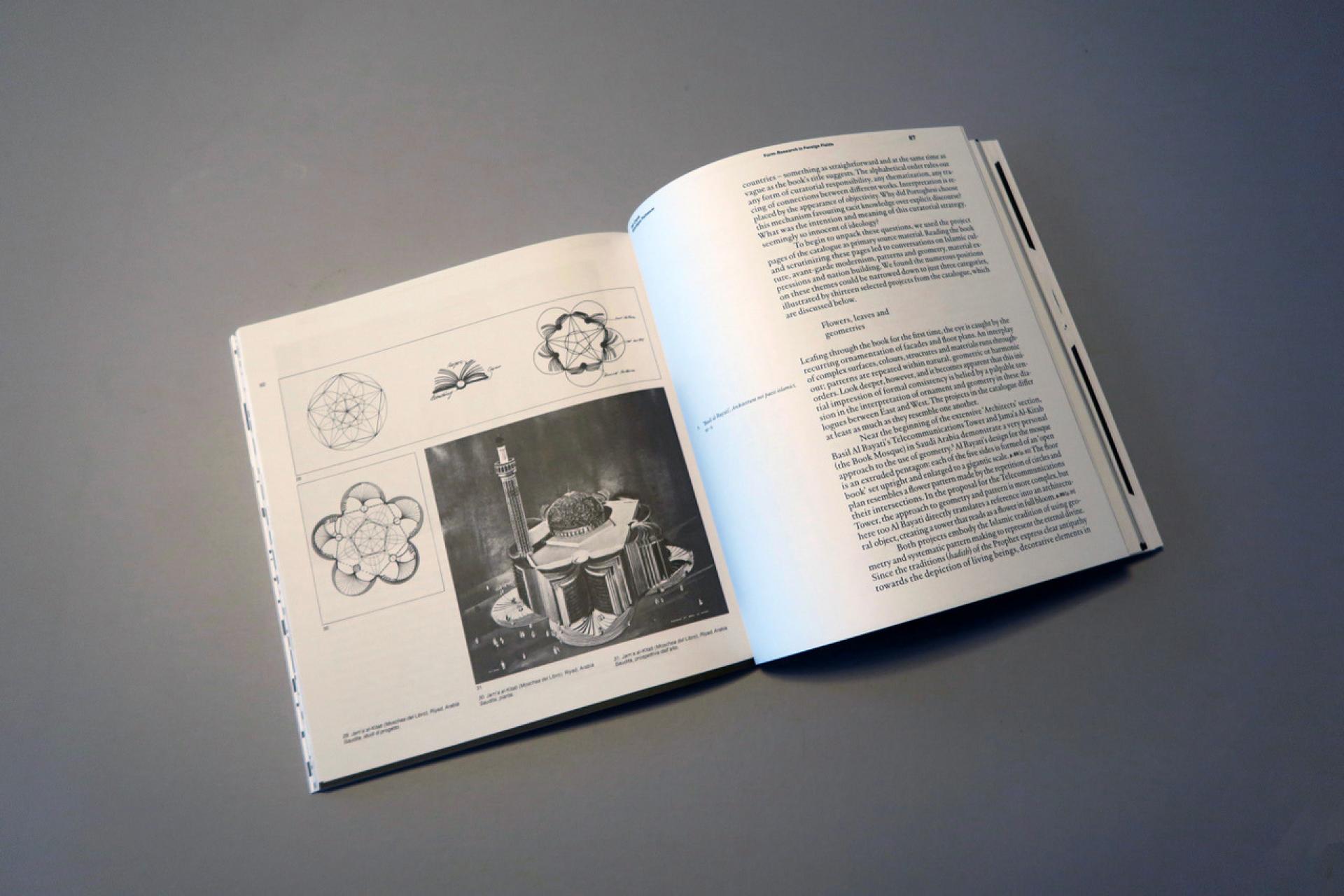

Exhibitions are a strange thing: they exist for a few weeks or months, then get dismantled and disappear forever. What is left are the publications, reviews in magazines or the Internet, and recollections in the mind of visitors. But catalogues get out of print, Internet pages are closing and memories vanish or get embellished. Therefore, when we discuss an exhibition, we often comment on a few black and white photos (especially before the rise of digital imagery) and texts found in libraries. Luckily, some academics dedicate their efforts to extensive research and give us a possibility to approach the concepts, questions, and debates that filled an exhibition. Following that principle, the book Architecture in Islamic Countries is a chance to discover the second Architecture Venice Biennial and to examine the early 1980s discourse.

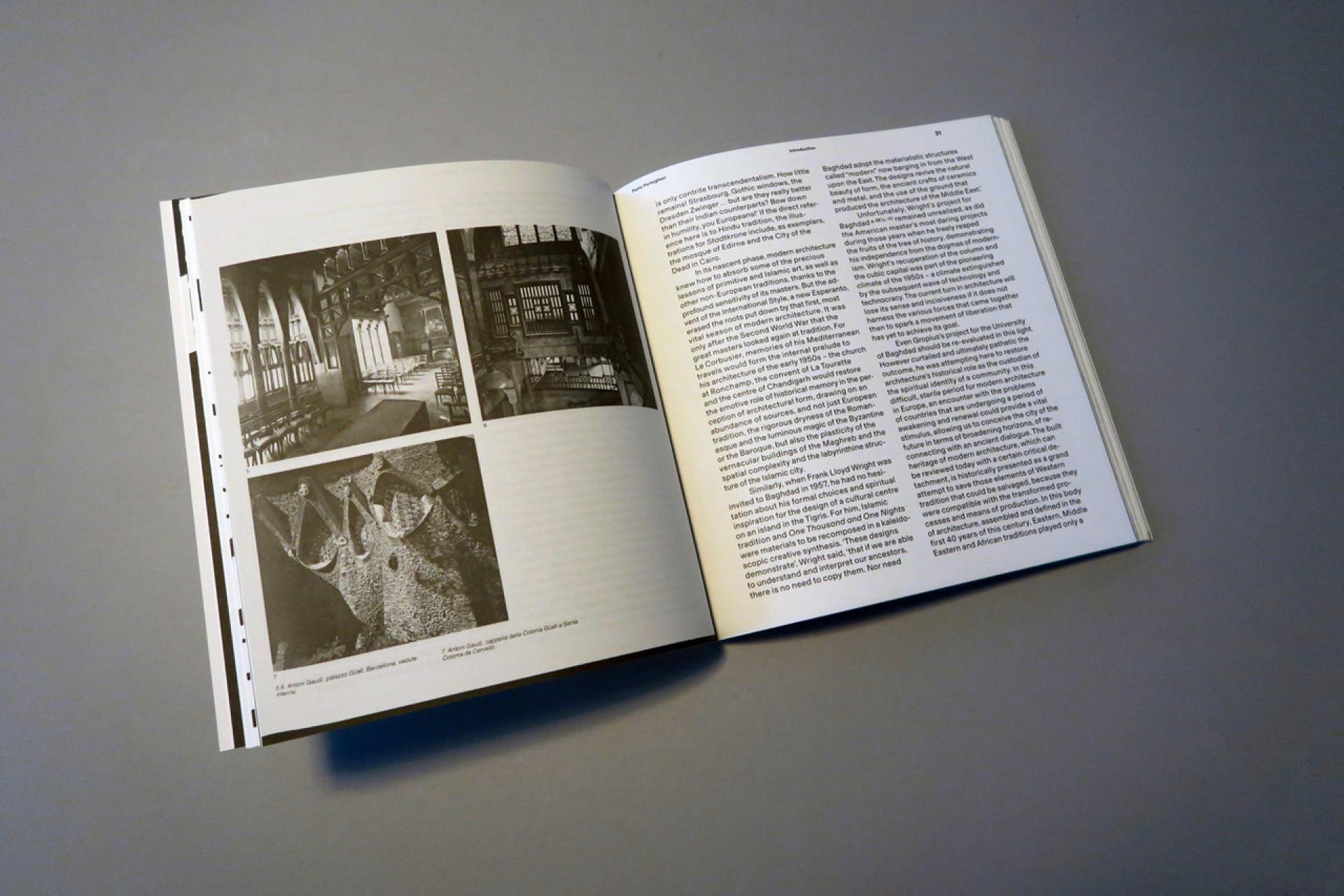

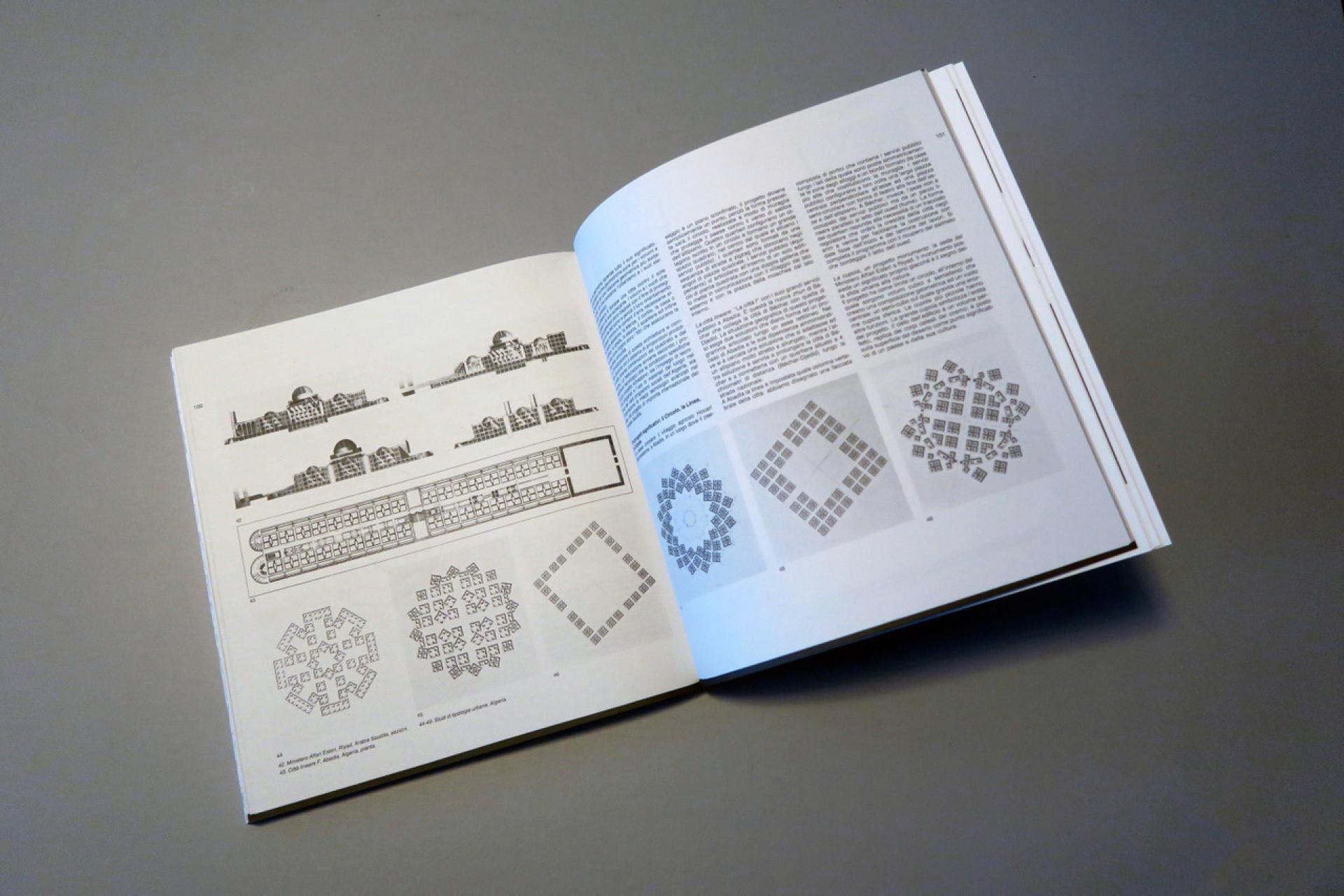

The volume offers a reprint of three original essays by Paolo Portoghesi, Mehdi Kowsar and Udo Kultermann published in Italian for the catalogue of 1983 and translated here into English for the first time. Helen Thomas, Esra Akcan, Aslı Çiçek and Véronique Patteuw delve into those historical texts and documents to examine their relevance today. Obviously, postmodernity is a dispute that has lasted and might seem behind us, while its aftermath – regionalism – has left disgusting marks in cities all over the world. But colonialism and post-colonialism are words that find resonance in many actual debates, and this edition of the Venice Biennial was loaded with those concepts. That second edition of the Biennial, in opposition to the first one, it was not about the restoration of ornaments, the (bad) taste or the return of fun into modernity. It was about a world that slowly gets globalised and a search for cultural roots in architecture. That makes this book a great reading, as the original texts are commented with a critical eye, commenting on the ideological and political positions of the actors from the biennale. (Akcan, for example, beautifully brings back the ‘fight’ that Bruno Zevi initiated in the press towards the biennial and its ideas…)

But what do we really learn here? That an exhibition that was not so well received at her time can become highly relevant 40 years later. Those questions that were (a bit) naively asked in the 1980s are still looking for an answer. That discussing the role of pure geometry in architecture (in an era of 3D nurbs and impossible shapes) could be something new. Last but not least, we realise that history is not written once and forever, and that we can always look at events, exhibitions or buildings from the past with a fresh eye.

-

Architecture in Islamic Countries; Selections from the Catalogue for the Second International Exhibition of Architecture Venice 1982/83, Edited by Helen Thomas; gta Verlag - source material, 2022