Mika Cimolini: On Critical Geometry

The first talk on the Independent Coastal Radio NOR on 2024 is with Mika Cimolini, an architect from Slovenia. For her very architectural product is the result of critical geometry in which economic, locational, programmatic, technological and structural parameters are negotiated with the user's daily routines. Listen to new edition of Weltraum.

Mika Cimolini | Photo © Mateja Jordovič Potočnik

Your work in architecture is continuously changing, from Elastik to media, from teaching to politics; what is your main focus?

Mika Cimolini: My main focus has been on conceiving architecture as an industrial product. Over the years, particularly during my collaboration with Igor Kebel on Elastik, we've developed methods integral to our project workflow, placing a strong emphasis on user-centric design. The nuances of everyday life have consistently been at the forefront of my attention, with a perpetual interest in exploring the dynamic interplay between private and public spaces and the evolving boundaries therein.

The method that we have developed and named the critical geometry meticulously considers various factors, including location constraints, limitations of the locations, and the materiality of con-structural elements. This comprehensive approach ensures a nuanced understanding of the intricate dynamics shaping architectural design. Continually intrigued by the fusion of industrial methodologies and architectural concepts, I aspire to bridge the gap between these realms. The goal is not only to enhance efficiency in the design process but also to contribute to the evolution of architecture by navigating the shifting landscape between public and private domains.

House Harmonika, Dolšce, Slovenia | Photo © Miran Kambič

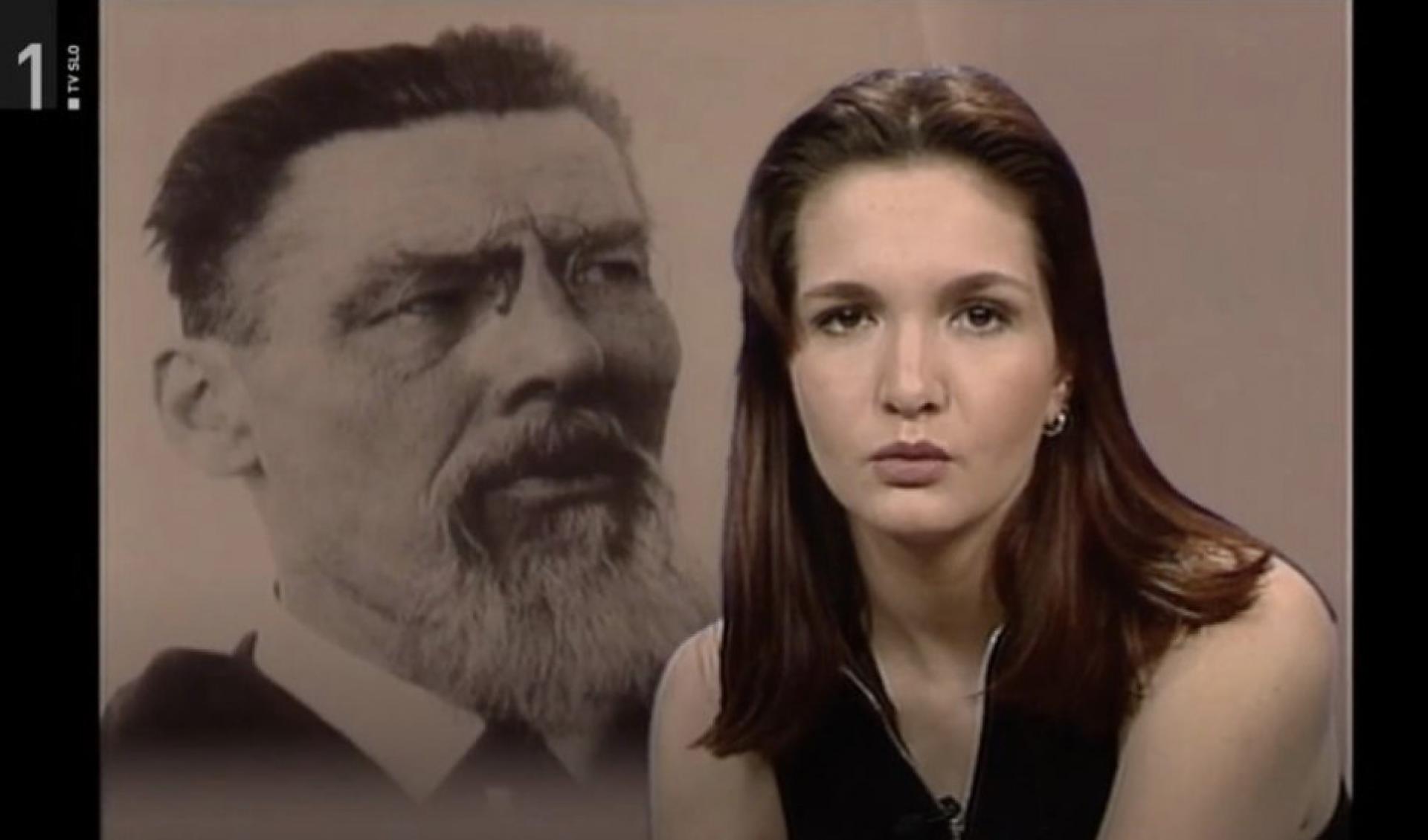

How has your journey as a journalist at the Slovenian national television influenced your career?

MC: My foray into the world of Slovenian national television began in the 1990s while I was still a student. This period provided ample opportunities for me to shape my perspectives and develop particular opinions. Interestingly, my focus at that time extended beyond architecture to encompass intermedia and body arts. It became a platform for delving into the margins of the arts, exploring radical social phenomena amidst a backdrop of political change.

The longevity of the Studio City show, spanning 30 years until its cancellation last year, held immense significance for me. It served as a crucial platform for affirming my perspective on various subjects. I devoted my entire - six years long journalistic career to this show, commencing at the age of 21. Studio City not only granted me the space to explore diverse realms but also facilitated the development of my opinions over the years.

Mika at the Studio City talking about Plečnik on Slovenian national television in the 1990s. | Photo Archive of the Slovenian national television

Why did you decide to leave the Slovenian national television?

MC: While pursuing my studies in the Netherlands, I came to the realization that my true interest lay in the materiality of things. Exploring how materials could be employed to initiate radical positions intrigued me. This perspective was a focal point of discussions during my time at the Berlage Institute with Pier Vittorio Aureli, today a prominent thinker of theory in architecture, then my fellow student. While Aureli advocated for architecture as an autonomous discipline, we were more inclined towards an inter- disciplinary approach. Throughout my academic journey, I remained focused on the user—examining how people engage with spaces, exploring adaptability in spatial usage, and seeking ways to enhance flexibility. I was particularly intrigued by the hybrid nature of architecture and the temporal aspects of space utilization. Questions such as: how we use space at different times and the potential for time-sharing became central to my architectural inquiries. This shift in focus ultimately led me to transition away from the television, storytelling and observing social phenomena.

What is your position on Jože Plečnik?

MC: In the 1990s, we grappled with the question of Slovenian national identity, and Jože Plečnik became entwined in that discourse, albeit often misused. Fast forward thirty years, and the trend of appropriation and commodification has only intensified. Now, there's even a brand of tea bearing Plečnik's name, despite having no connection to him whatsoever. I strongly opposed such appropriations, as they divert attention away from his substantial body of work.

Mika's text in Slovenian magazine AB "Packaging Architecture: Plečnik VS. Herzog De Meuron"

You have been working at the Museum of Architecture and Design MAO in Ljubljana; what is the future of such a museum?

MC: My role at the Museum of Architecture and Design MAO involved leading the program at the Center of Creativity, the first national platform dedicated to fostering creative industries in Slovenia. While the museum primarily delves into the architectural and design heritage of Slovenia, our focus at the Center of Creativity was forward-looking. We concentrated on initiatives to guide the creative sector towards a more business-oriented approach. Our approach embraced the concept of a hybrid museum, which, in my view, represents the future of museums. This entails operating at the intersection of the past and the future, allowing a museum to simultaneously engage with historical legacies and contribute to shaping the evolving landscape ahead.

Presentation of the Ministry of Culture's public call for "Encouragement of creative cultural industries - Center for Creativity 2019" with Anja Zorko, Mika Cimolini and Biserka Močnik.

I believe museums should consider their prospective visitors for the future. While museums function as research institutions, they shouldn't confine themselves solely to academia. There's a need to communicate the narratives of the past and the future to a wider audience. A noteworthy experience during my tenure at the Center of Creativity was a lecture by car designer Robert Lešnik. The lecture hall was filled to capacity, predominantly with males in their late thirties who may not have previously considered visiting a museum. This is how I envision development of the museums’ audience.

What about the engagement in the Chamber of Architecture and Spatial Planning of Slovenia, you were taking part at some commissions at the Ministry of Culture in the past?

MC: I was never in the position to create policies but I was very often in the position to offer advice. Since becoming a member of the Chamber of Architects and Spatial Planners of Slovenia in 2009, I've been actively involved in restructuring the chamber to enhance its proximity to members. Initiatives such as awards given to the best realized work, fostering a more democratic and international approach. We were actively contributing to the implementation of architectural planning processes into laws – to bring them closer to the way we practice. We've seen success in these endeavors, and I am committed to furthering this work by advocating for an open and policy-oriented chamber, aiming to improve the position of architecture in society

Opening of the exhibition The Future of Living: Berlin in cooperation with the Centre for Creativity/MAO. | Photo © Jože Baša

Are these ideas coming from your experience of living and working at the Netherlands?

MC: Indeed, I believe they do. In the Netherlands, architecture plays a significant role in shaping the national identity, and their modernity is deeply intertwined with architectural and urban planning achievements. While there may be some ongoing struggles, particularly due to conservatism in architectural production, urban planning remains a central focus of public discourse in the country.

How about Slovenia?

MC: Following natural disasters and floods, there has been a heightened recognition of the importance of urban planning in Slovenia. The focus has shifted towards understanding the significance of urban planning. However, challenges arise when it comes to municipalities and the practical execution of urban planning. The influence of local politics often supersedes recommendations from urban planners, posing significant obstacles. This issue is a key concern for the chamber, emphasizing the need to make local municipal governments aware that disregarding spatial planning rules can lead to problems in the face of natural disasters. Neglecting urban planning as a discipline tends to result in the persistence of issues, with poorly executed architecture proving to be problematic and unsustainable in the long run.

What was your experience practicing architecture in the Netherlands?

MC: I haven't been actively practicing in the Netherlands for the past few years, so I may not provide recent insights. However, I've heard that there has been a shift towards conservatism in terms of architectural production. A notable setback was the cancellation of the Netherlands Architecture Institute, resulting in a decrease in architectural discourse and public debate. Institutions like these play a crucial role by consistently addressing important themes and fostering an environment for debates where architecture takes center stage.

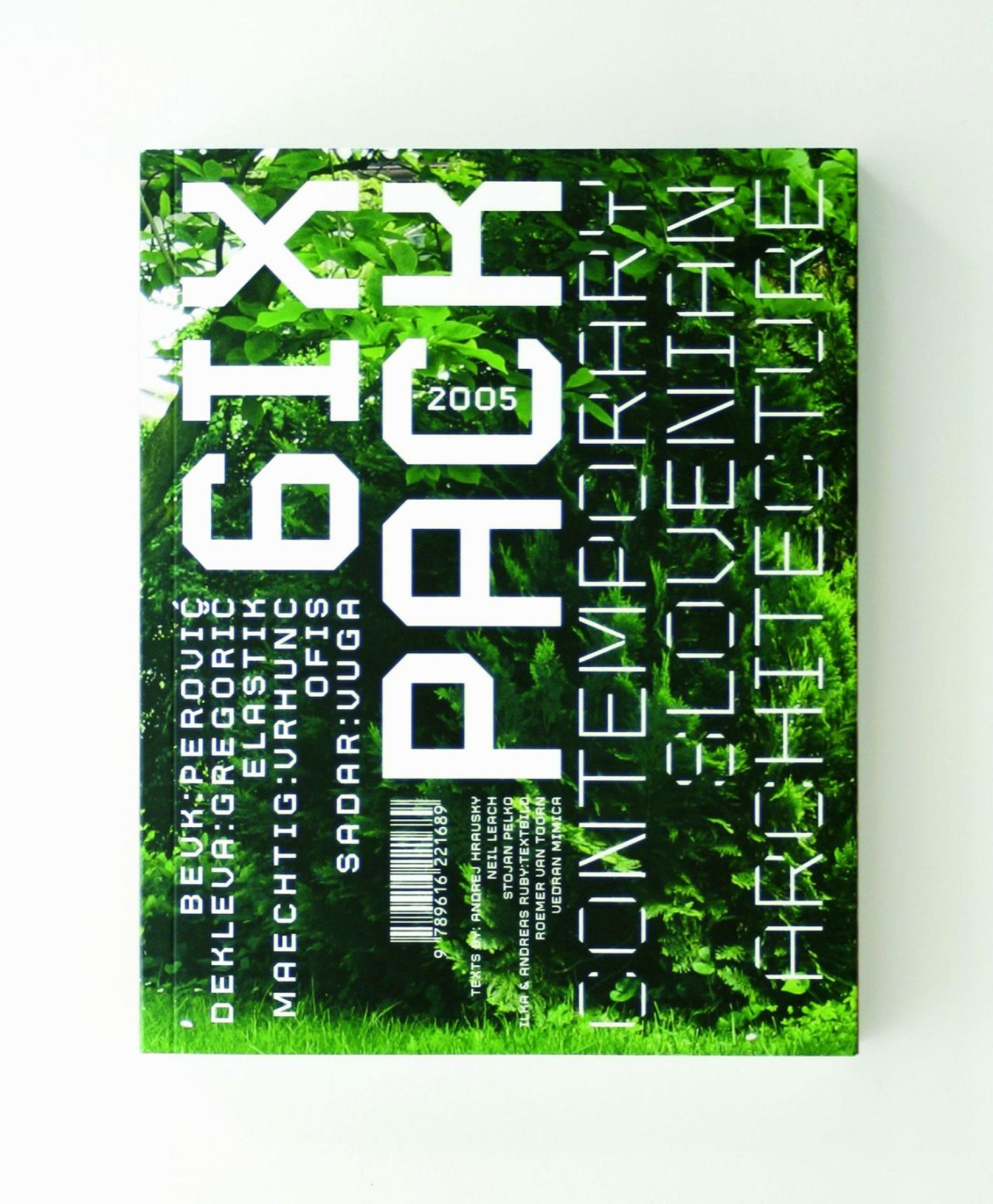

Could you elaborate on the SIX:PACK phenomenon?

MC: The SIX:PACK comprised of six - then young - Slovenian architectural firms (Bevk Perović, Sadar Vuga, Dekleva Gregorič, Elastik: Kebel Cimolini, Mächtig Vrhunc and Ofis: Oman Videčnik), each of which had pursued studies abroad with the shared goal of enhancing their skills and bringing newfound knowledge back to Slovenia. In the 1990s, there was a unique opportunity for young offices to thrive in Slovenia, given the vast empty space in the architectural landscape and the feasibility of winning competitions. However, as I curated the exhibition "New Praxis New Tools" featuring ten young Slovenian practices today, it became evident that the dynamics have shifted. Contemporary practices now find themselves relying more on private clients and facing heightened competition for substantial projects. The architectural vacuum that once existed in the 1990s has dissipated.

The 6IX:PACK traveling exhibition of contemporary Slovenian architecture.

During the era of SIX:PACK, we were considered exotic curiosities as awareness of contemporary architecture from the East was limited. We engaged in discussions about political change and explored how architecture could shape the identity of the emerging country, Slovenia. Present-day architectural firms no longer enjoy the same unique position; they address similar themes to their Western counterparts and have lost some of the exotic allure. The field in Slovenia has become somewhat formulaic, with only a few standout projects emerging from the prevalent average architecture that has become the norm. Clients, too, increasingly favor these norms, making it challenging to pursue more radical and innovative architectural endeavours.

Is this influenced by the education at the Faculty of Architecture in Ljubljana?

MC: I don't believe so, as our education back then was even more challenging. In Slovenia, the situation is now becoming more akin to what I experienced in the Netherlands, where individuals typically start working in architectural offices immediately after graduation, around the age of 25. This early entry into professional life often limits the opportunities for exploration. By the time one reaches the age of 50, they might be considered relatively older, possibly retired, and only then might they have the freedom to engage in more experimental pursuits. Probably too late?

Are you actively involved in promoting the work of women in architecture through the Chamber of Architecture and Spatial Planning of Slovenia?

MC: My engagement in projects related to women in architecture began after a significant travelling exhibition we organized in collaboration with our Austrian counterparts in 2017. Their initiative aimed to showcase the contributions of female architects and bring attention to the significant presence of women in the profession. What we discovered during that initiative was that nearly half of the practicing architects, who are members of the Chamber of Architecture of Slovenia, are female—a substantial percentage, significantly larger than in Western countries.

In the West, there's often a trend where women leave the profession after having children, either stopping work altogether or opting for occasional part-time roles. Conversely, in Eastern countries, such as Slovenia, women tend to balance family and profession simultaneously. It's a tradition that harkens back to our mothers' experiences in Yugoslavia, where being a female engineer or architect was not an anomaly but a natural part of professional life

Publication of the Women in Architecture project in Slovenia.

Our research, conducted as part of an European Union research project, called Yes We Plan on females in the architecture and engineering professions, revealed a significant disparity. Few female architects receive national awards for their work, and there's a notable absence of women in crucial leadership positions. Despite their competence, female architects tend to be overshadowed.

During my candidacy for the presidency of the Chamber, where I came close to securing the position, I observed that even though young female architects supported my candidacy, there persists a perception that architecture is a male-dominated profession. This perception is noteworthy as female architects often bring unique perspectives to the table, considering topics that are frequently overlooked, such as adapting spaces for the elderly, mothers, and children. The inclination of female architects toward community and societal considerations surpasses that of their male counterparts. It's crucial for young girls to recognize that they can pursue any career and have female role models in architecture. Breaking down stereotypes is essential for fostering diversity and ensuring that female architects receive the acknowledgment and opportunities they deserve.

How do you see architecture in the future?

MC: Certainly, we will witness an increase in renovations and a decrease in new construction, the available spaces for building are becoming more limited. The emphasis will shift towards responsible building practices, considering the location and environmental impact. The interplay between private and public spaces will gain prominence, particularly as media intrusion blurs the lines between them. Simultaneously, there will be a rise in public life occurring within private spaces, exemplified by settings like shopping malls. However, there is a concern about avoiding a scenario akin to the U.S., where a lack of public spaces in cities is evident. I anticipate a more controlled approach to public spaces in the future, with a heightened awareness of their significance and purpose. The challenge lies in striking a balance that respects both environmental sustainability and the evolving dynamics between public and private domains.

I perceive a somewhat bleak scenario concerning public space; the concept of "publicness" seems destined for a transformation to elsewhere. The public space is transferred to virtual spaces, to social media etc. In my recent piece, "The Fight for the Public Space", I delve into how the physical manifestation of publicness in our squares has become nearly impossible due to the disappearance of public discourse.

ATAR installation with David Tavčar.

Mika Cimolini graduated from the Faculty of Architecture in Ljubljana and received her master's degree from the Berlage Institute in the Netherlands with research focusing on implementing product design and marketing strategies into architectural organizations. During her studies she worked as a journalist at RTV Slovenia for the Studio City and for the internationally renown architectural office UN Studio in Amsterdam. Together with Igor Kebel, she co-founded Elastik, which was among others part of the internationally acclaimed travelling exhibition of contemporary Slovenian architecture 6IX:PACK. At the same time, she co-founded Hikikomori with Aron Boršo and Aljoša Rot that focuses on combining architecture with multimedia. She was the Head of Program Management of the Center for Creativity, the first national interdisciplinary platform for development of the creative industries in Slovenia, that operates within the Museum of Architecture and Design in Ljubljana, Slovenia. She curated and co-produced several design, architecture and museum exhibitions. For example the exhibition on the 50th anniversary of the REX chair by Niko Kralj in the Modern Gallery and the exhibition on Housing non/policies, produced within the Chamber of Architecture and Spatial Planning of Slovenia (ZAPS). With her involvement in the media she has drawn attention to the cultural dimension of the architectural discipline. She has been active within the Chamber of Architecture and Spatial Planning of Slovenia (ZAPS) for many years, presently as Commissioner for Communications and Events. She lectured at various professional events and faculties, including at the Berlage Institute, TH Köln and the Faculty of Architecture Ljubljana.

Here You can listen to the WELTRAUM interview.