FOMA 20: Post War Monuments in the UK

In this edition FOMA travels to UK. Architcetuul’s intern Lovro Novak prepared for the very first time a story about the post war forgotten masterpieces. Let's learn more about post war FOMA!

After the second world war, most of the British cities had been heavily damaged by bombing. Following that, the cities were in need of new housing that had to be built in a short time. In the UK the government financed many of housing projects as well as new public buildings.

The first built part of the Barbican Centre in London was Milton Court, which was used for public services. | Photo by Malcom Riley

Most of the newly developed architecture was designed in a Modernist form as it was the most functional, least expensive and the fastest way to replace pre-war buildings. Much of that post-war Modernist and Brutalist architecture has been neglected in the past three decades and was therefore disliked by many people. Some of those pieces of architecture have been renovated and reestablished in their environment. There are also several buildings that were inventive and experimental at that time but have later been abandoned or demolished for different reasons.

In 2008 Milton Court was demolished after several failed attempts to keep it as an important post-Blitz architecture of London. | Photo via C20 Society

Many post-war British architects were looking up to Le Corbusier’s concepts. Those inspirations resulted in many architectures reflecting Corbusier’s most notable works. His design for Shodhan House had an impact on Chamberlin, Powell and Bon, the architects who had created plans for Milton Court, which was a part of the Barbican Centre in London.

Milton Court had been the first built part of the Barbican and was used for public services. It was later connected to the rest of the complex by two concrete bridges. London’s government and planners had decided to have Milton Court demolished as according to them it didn’t aesthetically fit in the Barbican Centre. As it was not protected unlike the rest of the complex that was not so difficult to make.

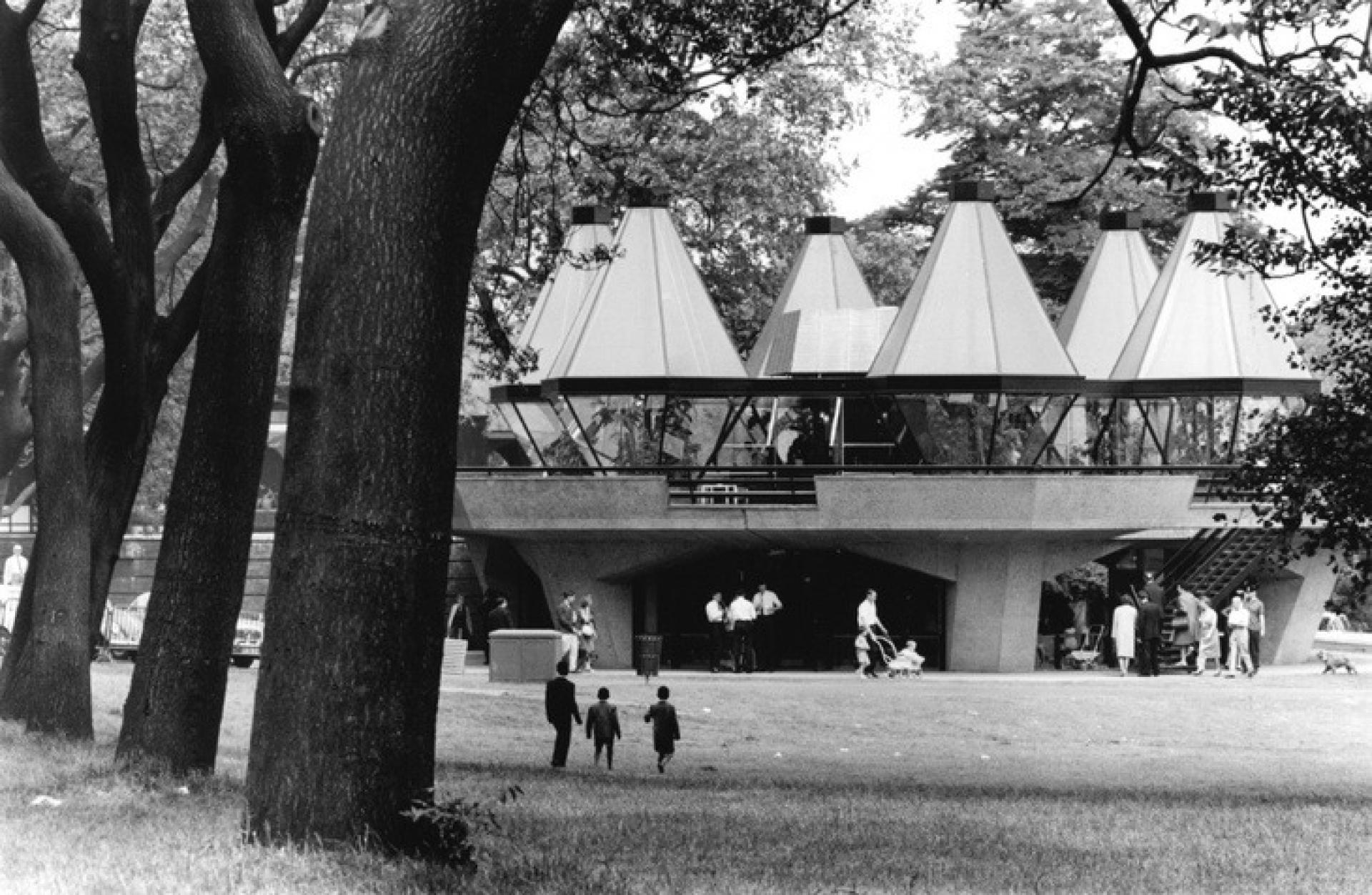

The indoor part of the restaurant was covered by glass pyramid-shaped roofs, which were the most famous characteristic of the building. | Photo via Londonist

Five years after Milton Court was completed, Serpentine Restaurant was opened in London’s Hyde Park. In 1964 was one of the two new restaurants in the park. It was designed by Patrick Gwynne who also looked up to Le Corbusier and Mies van der Rohe. He designed Serpentine Restaurant as a series of concrete terraces, which serviced as a dining area with a view over a pond and as a shelter for service rooms underneath the concrete structure. Gwynne designed furniture and interior as well and tried to keep cars away from the restaurant so the guests could enjoy natural views. This much-liked restaurant was extended twice and was demolished in 1990. Its only reminder is Dell Restaurant which still stands across the point overlooking Serpentine’s former location.

The most interesting features of the Derwent tower were open water tanks with the capacity of storing 10,000 gallons of water. | Photo via Derelickplaces

Another lost post-war building was Derwent Tower also known as Dunston Rocket. Unlike Milton Court and Serpentine restaurant, it stuck out in the landscape that is mainly built up by detached houses. It was an 85-meter tall residential high-rise in Gateshead close to Newcastle upon Tyne, designed by Owen Luder. As a part of a new residential complex it was built on a caisson foundation, which at the same time served as a spiral garage. To strengthen the concrete structure standing on the unstable ground, external flying buttresses were added. Derwent Tower faced a lot of infrastructure failures because of a very experimental construction. This was one of the main reasons why the demolition of it, which took place in 2012, was almost inevitable.

The tower consisted of concrete and looked like a rocket during construction (therefore the nickname Dunston Rocket). | Photo via Derelickplaces

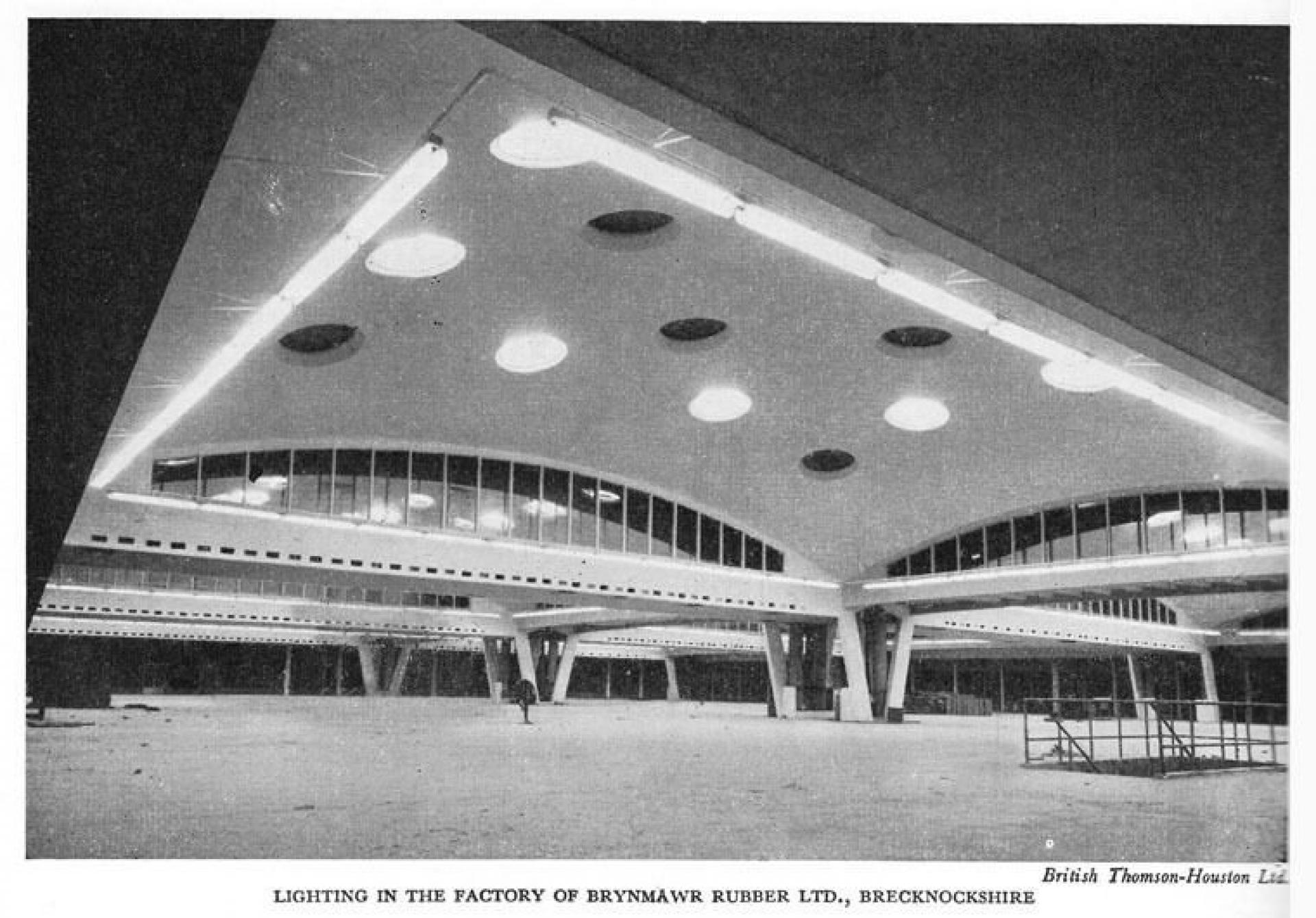

Unlike Derwent Tower, Brynmawr Rubber Factory in South Wales had a structure that maintained a human-scale. The complex consisted of the main hall covered with nine concrete dome shells and several small buildings. The domed shells were 90 mm thick and had circular roof lights. V-shaped columns were supporting shells in each corner, that allowed the roof to be thin without adding any extra columns. The shells were connected together at the edges and reached a height of, 4,3 meters. All other surrounding small halls had concrete barrel vault roofs.

Even F. L. Wright visited the factory because it was considered an architectural masterpiece at the time. | Photo via Disegno

It was closed in 1982 and demolished in 2001, though the local government tried to convert it into a cultural and sports center.

The Brynmawr complex was used for producing rubber and PVC flooring and was one of the major employers in the region. | Photo via Grace’s guide

St. Peter’s Seminary is an abandoned building in Cardross, Scotland, which used to house a Catholic seminary for 14 years. The seminary is consisted of two parts: an old Victorian mansion and a new Modernist complex. The new part had a capacity of a hundred students and was divided into four blocks, each had its own function. What sets this complex apart from other Modernist buildings are terraced rooms, windows inspired by Notre Dame du Haut and an altar in the seminary. The whole new part of the building has been under the highest level of protection in Scotland since 1992.

This seminary replaced an old one damaged in a fire. | Photo via GSA Archives and collections

Despite being protected the St. Peter’s Seminary is still abandoned. | Photo via GSA Archives and collections

There are many other examples of Modernist and Brutalist post-war architecture in the UK that have been neglected or even demolished. This era of architecture is still not appealing to the general public, though attitudes towards it are changing slowly. Nevertheless, this form of architecture has had an important role in experimenting with different ways of making architecture relevant to the post-war UK. Those experiments became either failures or a success, that still have an impact on contemporary architecture. Modernist architecture might not be aesthetically appealing to many people today, but it might be appreciated in the future.

Lovro Novak (1997) is a student at Faculty of Architecture at the University of Ljubljana. He attend the third year of Urban Planning and Design undergraduate study. Besides making assignments, attending classes and learning, he takes part in editing Architectuul as a part of his internship. His interest in architecture and urbanism derives from observing how artificial and natural environment affect the space we live in and vice versa.