FOMA 42: Architecture Dead Language: The Case of Sagunto Roman Theatre Restoration

Some years ago, while working on my research regarding fragments and collective memory, I came across the book of Giorgio Grassi Architecture Dead Language (1988). The strong title-statement attracted me and engaged me to dig deeper into the world of Giorgio Grassi, his controversial restorations and eventually into the restoration of the Roman Theatre in Sagunto, Spain.

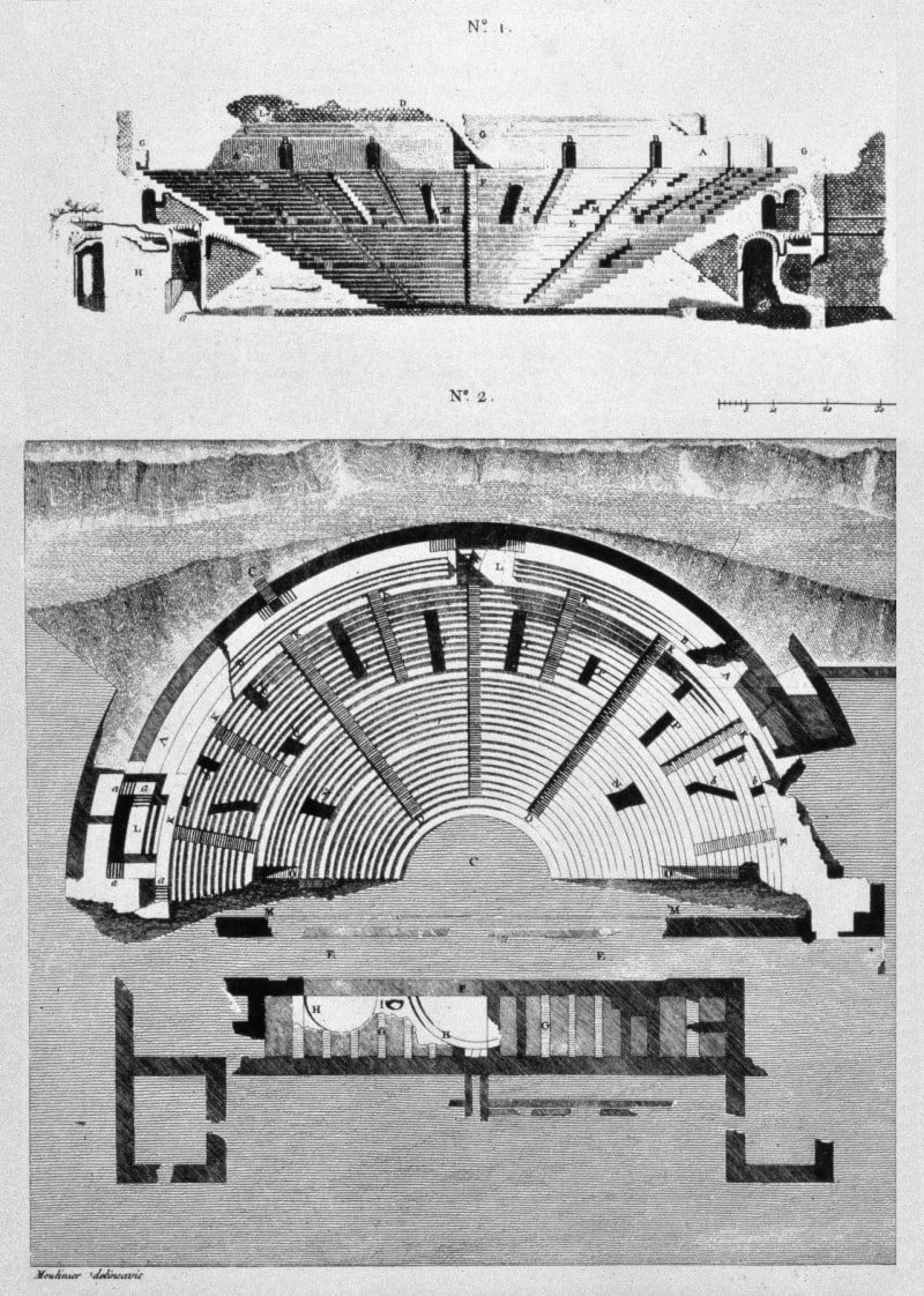

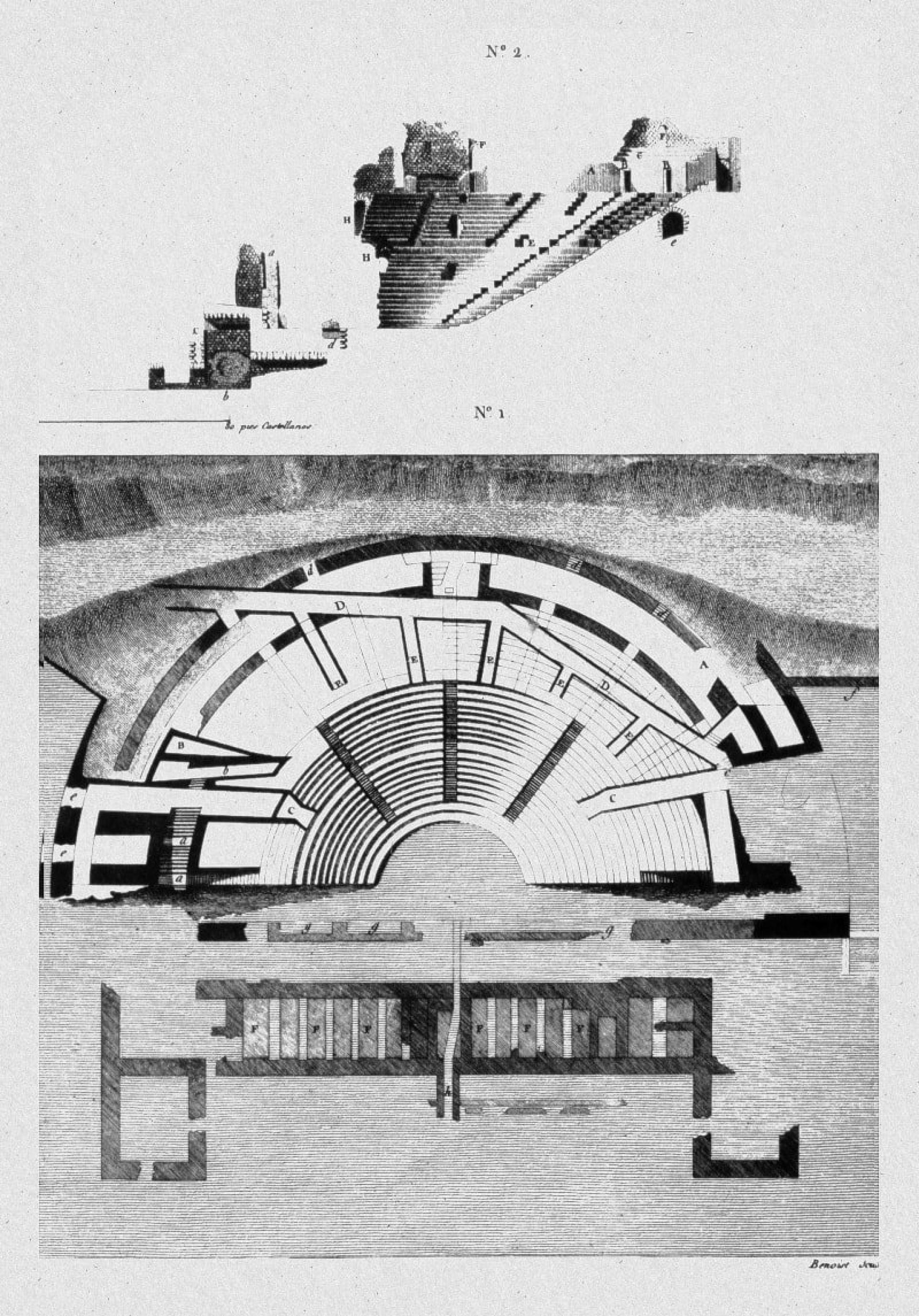

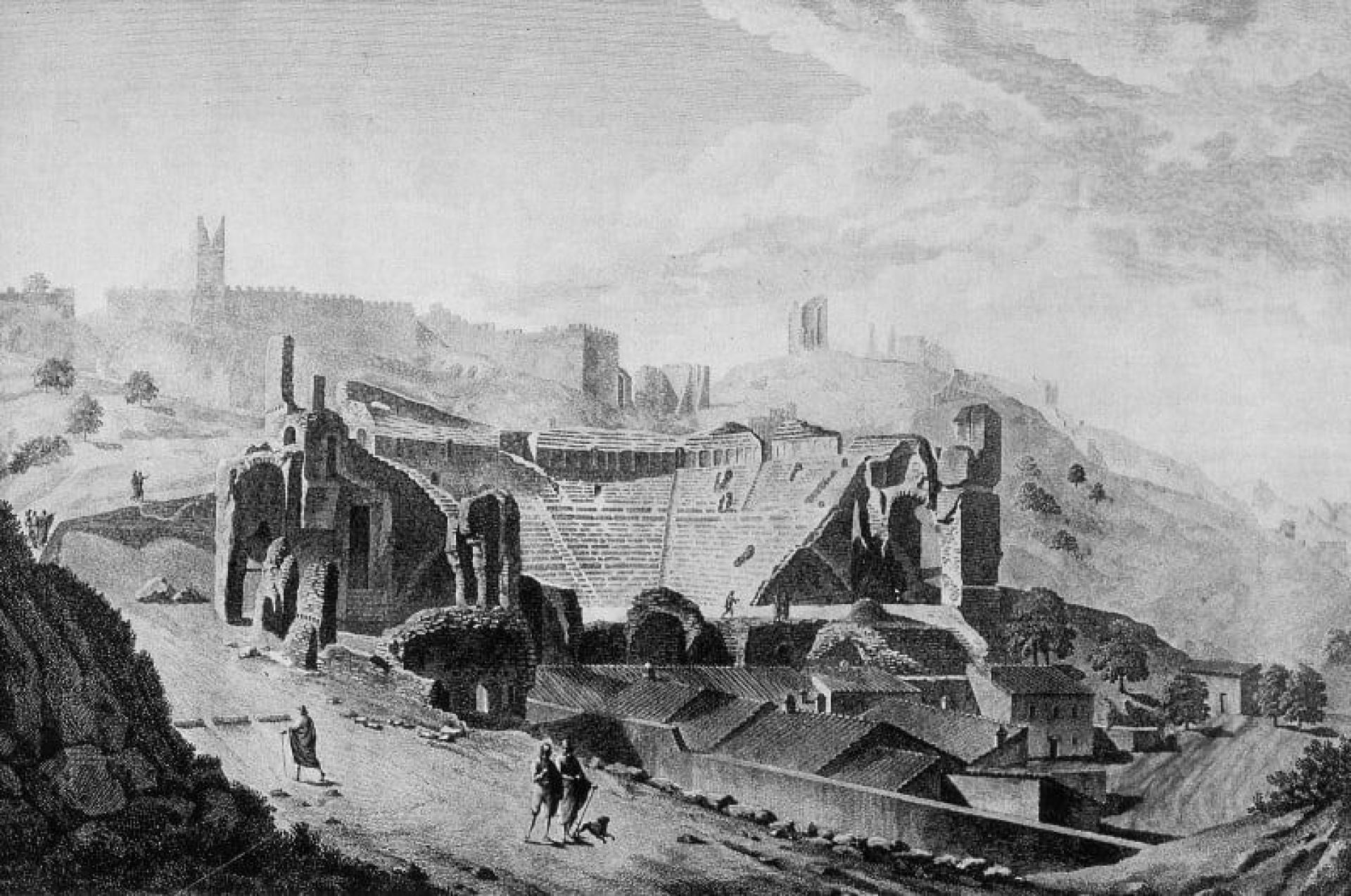

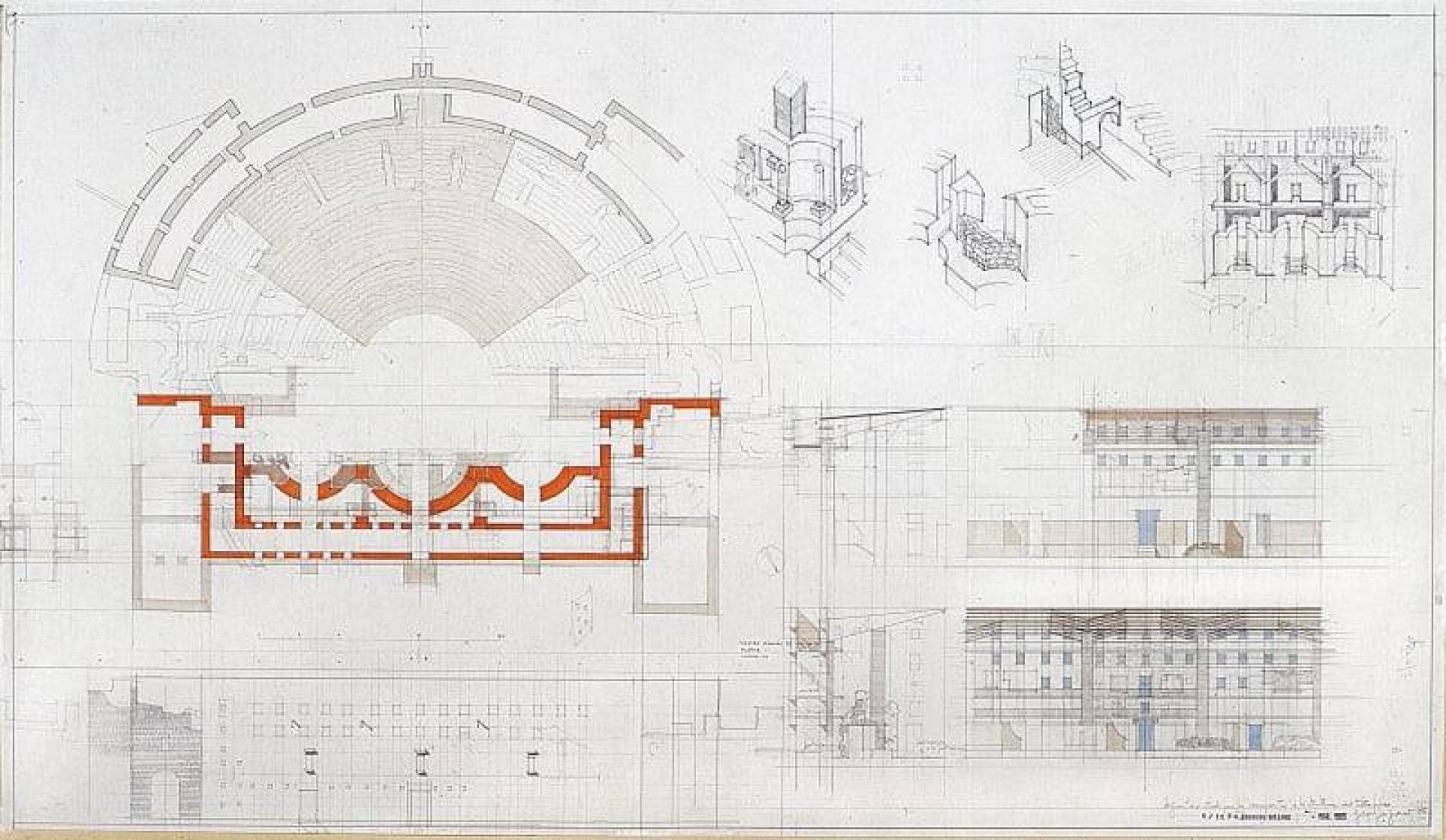

Grassi had been developing the book while he was working on a commission with Manuel Portaceli, requested by the Regional Government of Valencia to carry out a study for a potential intervention in the Roman Theatre of Sagunto. The building, constructed in the first century AD, suffered a gradual decay over a long period of time and eventually a series of conservation works led to a distortion of the original construction. Instead of the requested study, Grassi presented a complete restoration proposal based on the existing ruins and the roman theatre typology.

He suggested to demolish all the additions from the 20th century (which actually have altered the Roman typology into Greek), bring the ruin into his original state and eventually create an open museum with all the original theatre pieces. Despite the opposition expressed by many people in Sagunto, the work started in 1990.

Dead is a language that has no speakers and cannot be used to convey meaning. Grassi uses this analogy to talk about decayed pieces, about ruins. He explains that fragments of the past are impossible to reconstruct and make sense, because they have lost their context to which they referred, have lost their coherence and meaning thus becoming a “dead language”.

A still life whose only ability is self-projection. In this way the idea of architecture is interpreted, for Grassi, as a museum of objects. A museum is the place where all objects, moving in space and time, are exhibited as important works becoming merely images of themselves. His restoration works were creating a timeless context/background (like a boundless hall of mirrors) in order to display fragments with architectural value, fragments of memories which they were removed from their original places and their usual functions.

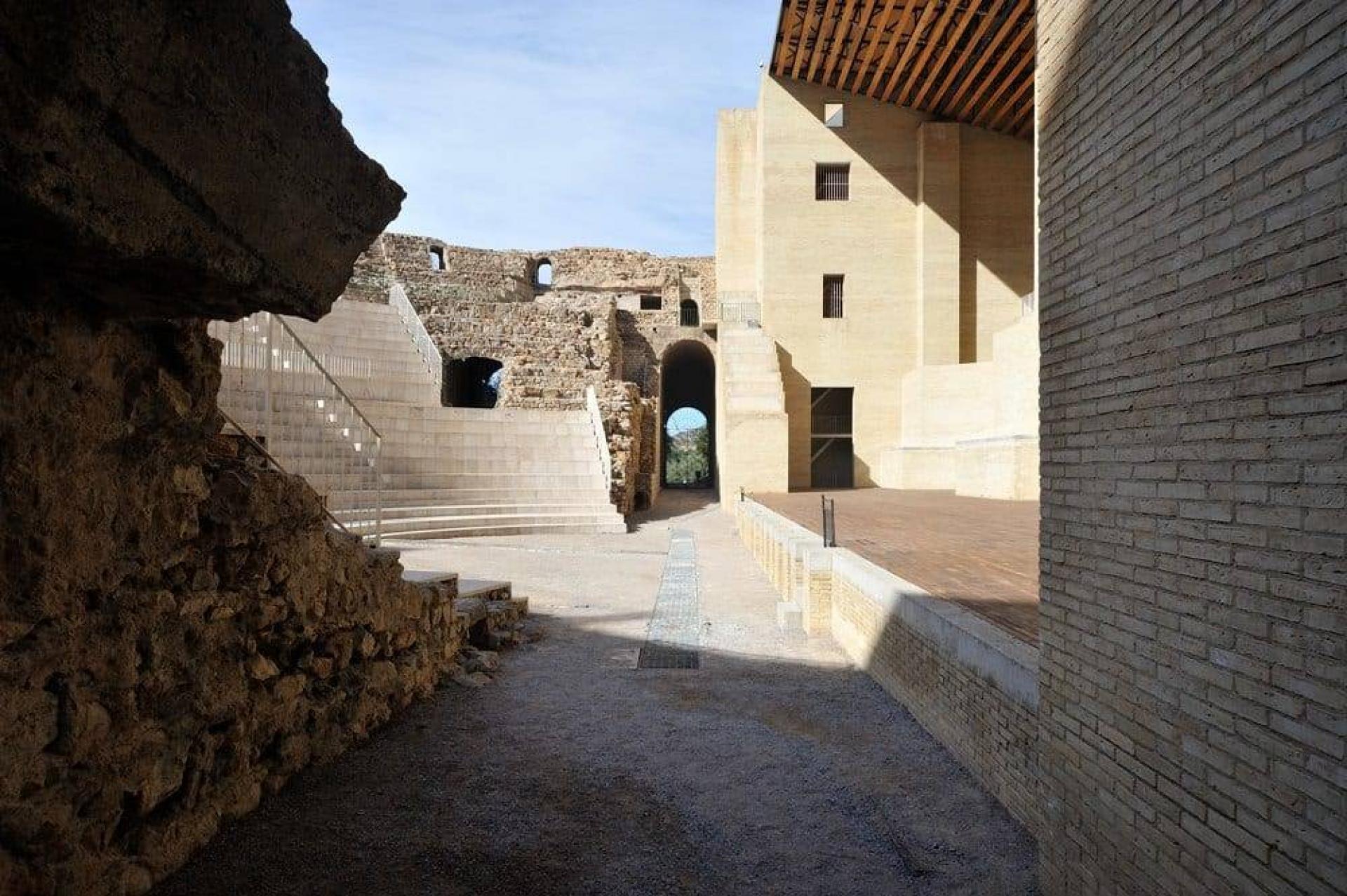

The architect’s work was limited to understanding and locating these fragments. In Grassi’s case the meditation on the essential in architecture is the rediscovery at the zero point, at the origin, of fundamental elements. The wall, the empty space, the place, the relationship with existing forms, the typology and morphology, the simple – too simple and archaistic in some cases – rules of construction.

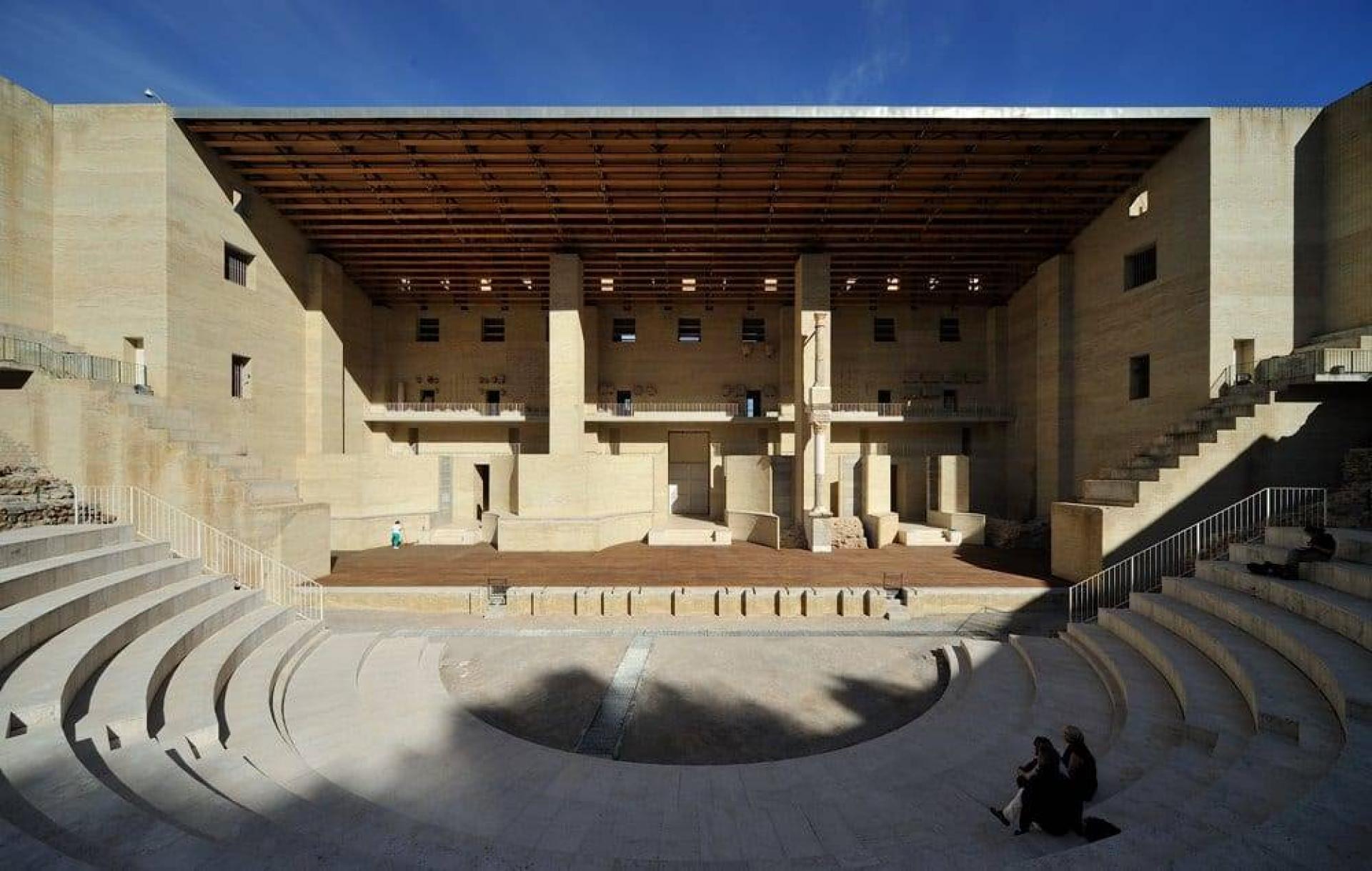

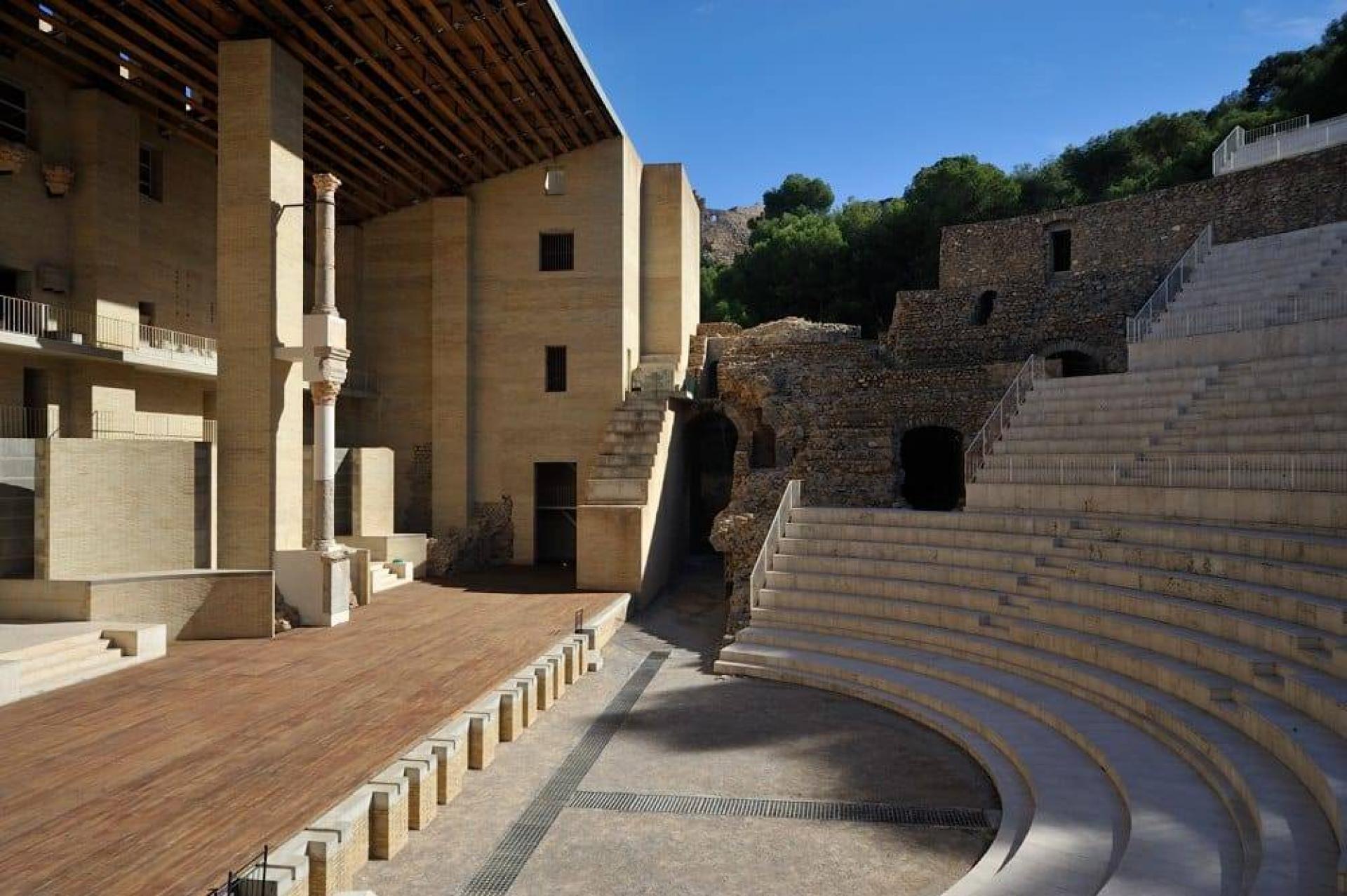

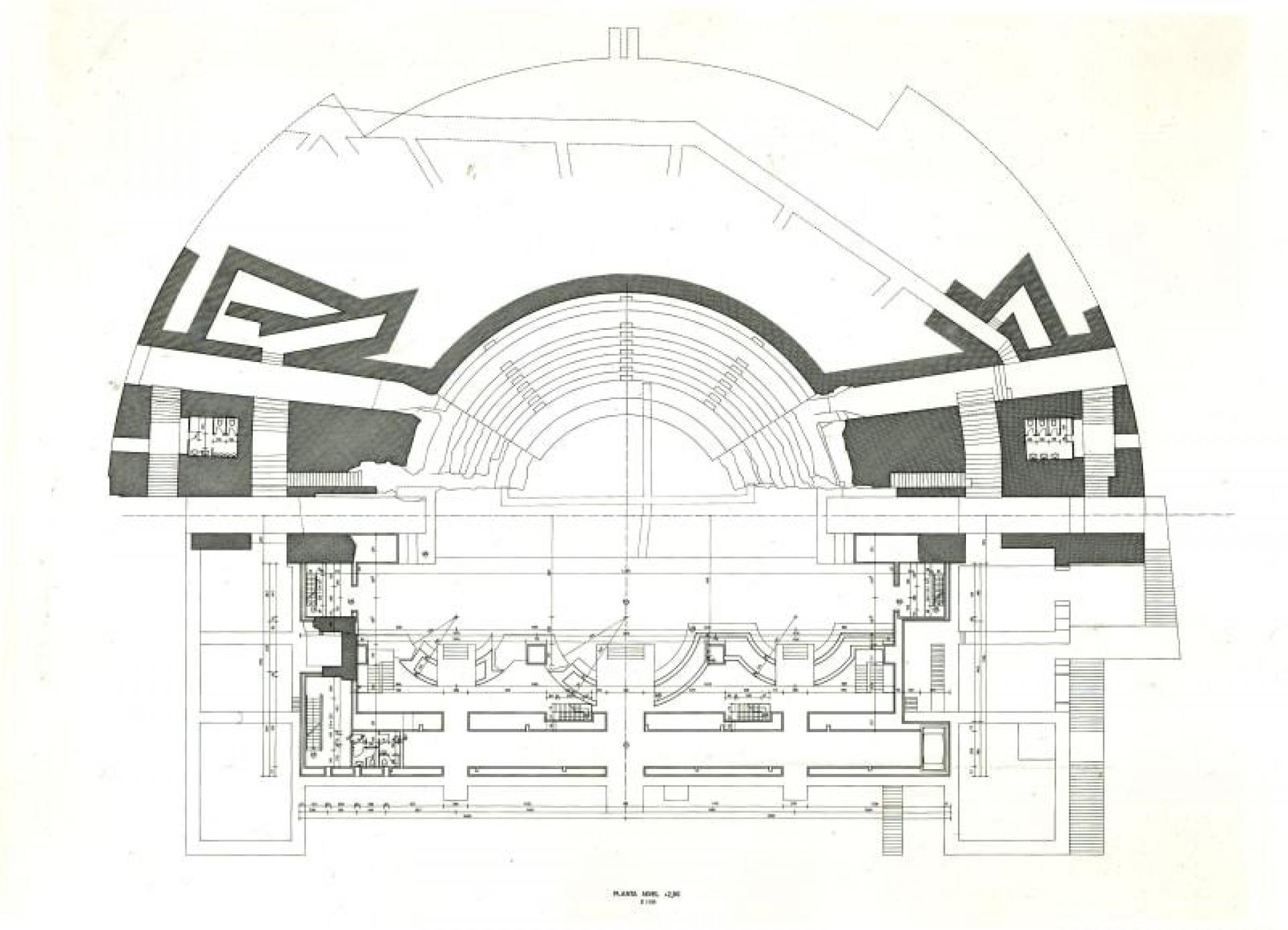

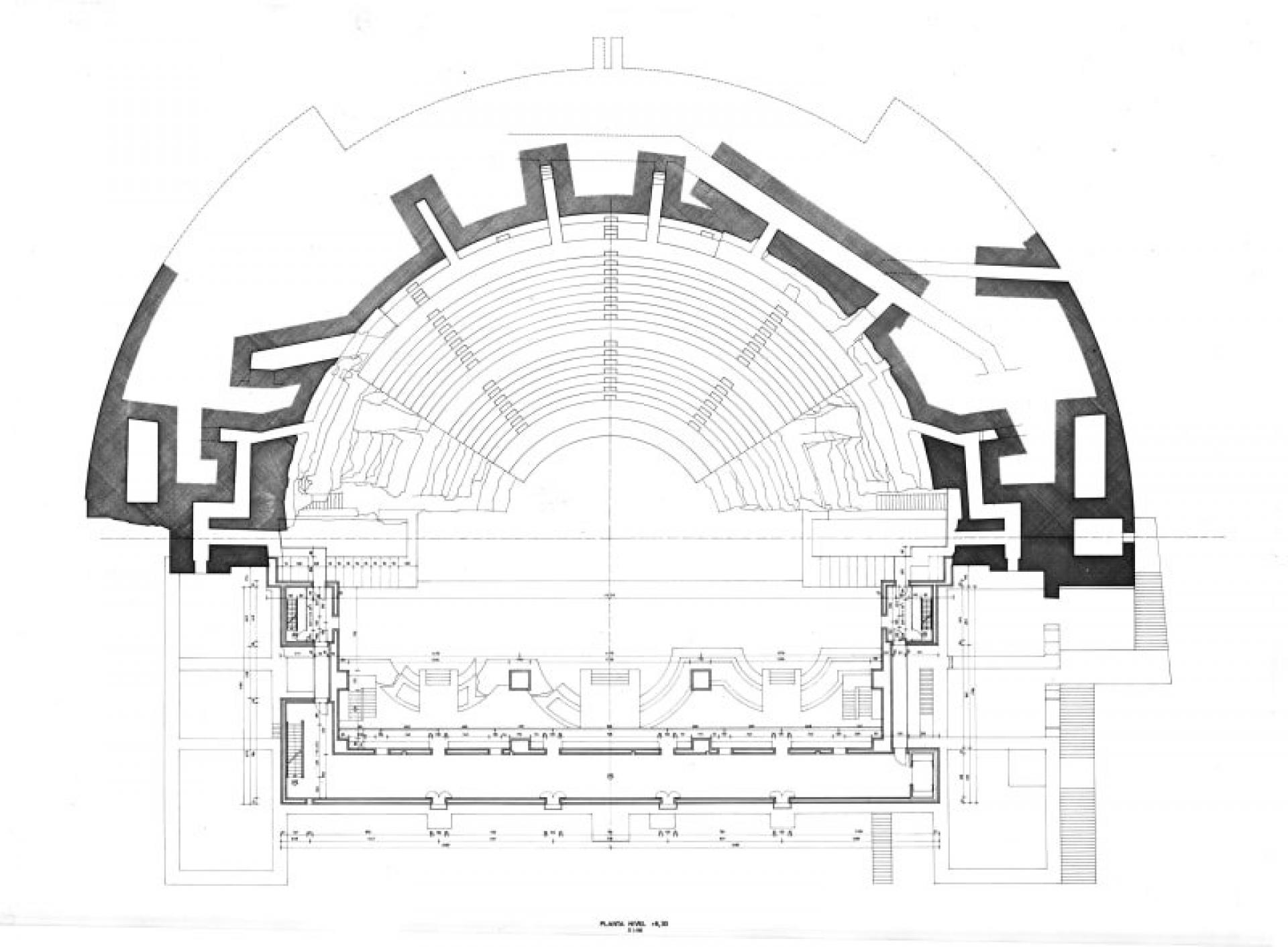

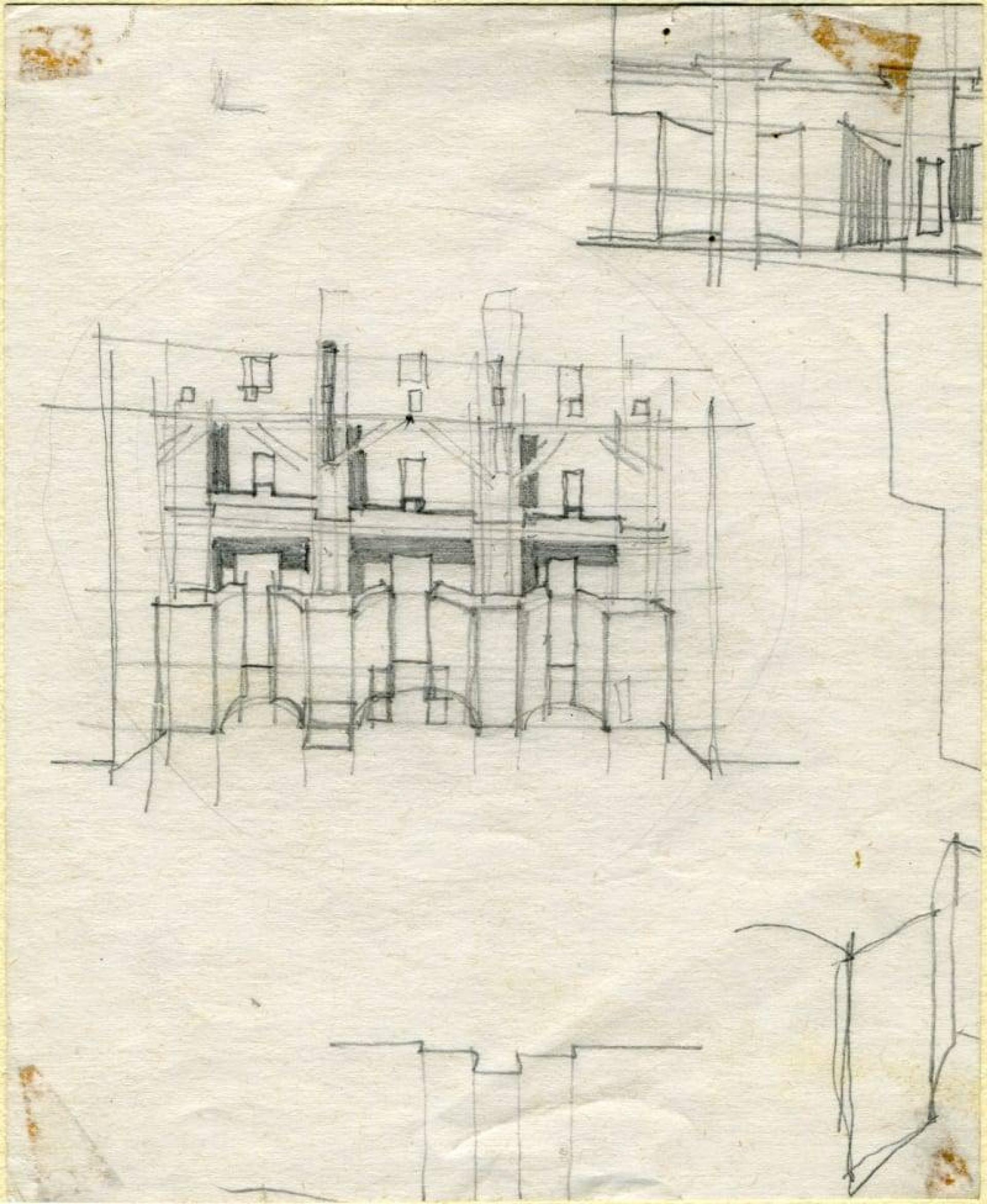

In this work, the ruins of the Roman theatre became literally the stones on which the new structure was constructed. According to Grassi, the value of the ruin is highlighted by the fact that it is always part of a whole. Thus, using the ancient fragments and with the aim of restoring the form of the Roman theatre, which had been lost from the previous interventions, the architect proceeded to the construction of the scene (scanae), which would be the border of the amphitheater (cavaea) and at the same time would complete the typology of the theatre. The scenewas for him “a space of fantasy in which architecture and theatre are intertwined”. [1]

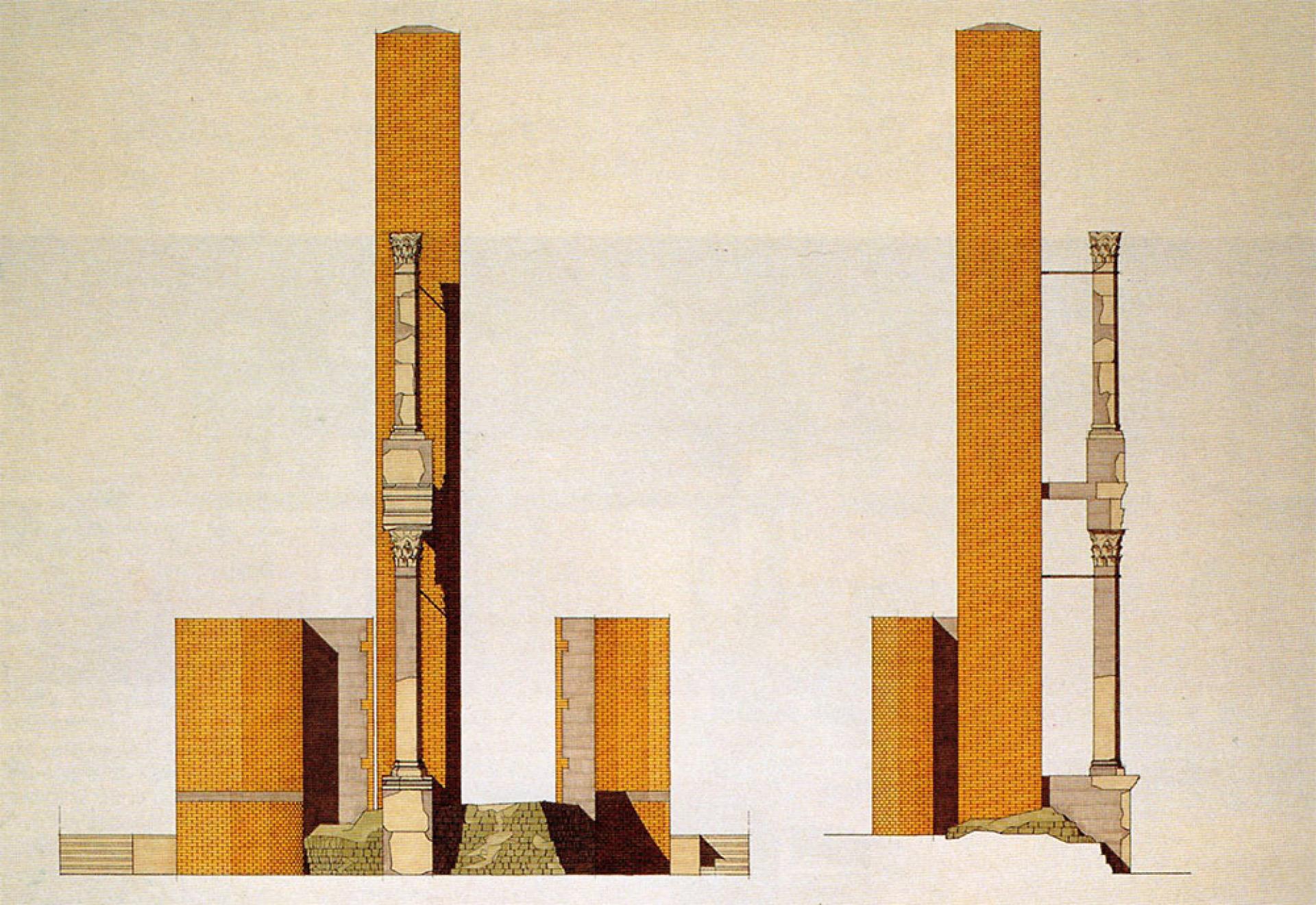

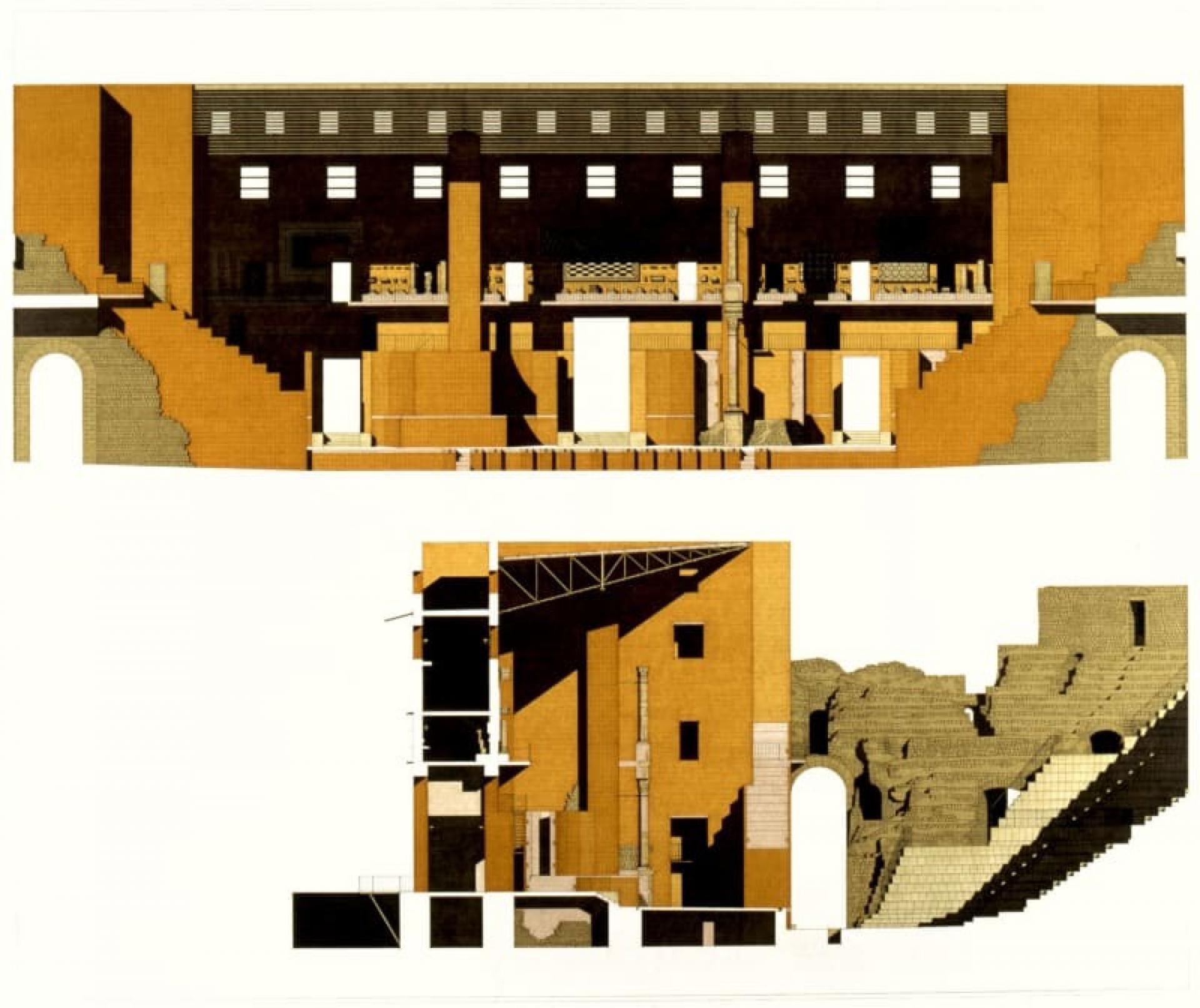

In general, the scene in Roman theaters was a special and flexible place. It was divided into two levels (in contrast to the ancient Greek), of which the first level (pulpitum) essentially connected the stage with the orchestra and was the place of action of the actors. Grassi describes it as the ’useful part’ and reconstructs it from the remains of ancient fragments. The second and upper part of the scene (frons scanae) was rebuilt, retaining the most important elements of its typology: the three entrances.

The other openings throughout the stage do not take part in the action, but are necessary for acoustic reasons. Grassi followed a strictly architectural system in the restoration of the whole theatre stage, since it was the most fundamental feature of the Roman theatre, which remained unchanged over the years.

Reconstructing the upper part of the scene (frons scanae) was the most demanding and detailed work of the whole intervention, since Grassi literally created an open air museum. The architect worked on dismantling an old archeological museum, located at the base of the Roman theatre, which exhibited material from the ongoing demolition of buildings in the historic center of the city. Most of these exhibits consisted of pieces of decorative elements, parts of statues and some larger pieces of mosaics of special value.

Grassi, placed all these spolia on the theatric scene turned into an architectural iconostasis. He also, used the larger exhibits at the lower level of the stage, recalling the composition of the ancient Roman scanae, with great immediacy. Thus, the whole stage witnessed the brilliance of the ruin, while at the same time it reminded of “the densely decorated theatre scene found in the illustrations of old art history books.”[1] Grassi somehow, managed to reveal the internal mechanisms of the scene, turning it into the fantastic place it used to be and at the same time a spectacle of itself.

Regarding the amphitheater, a partial restoration was carried out, with the central sector being its only renovated part. The ruin remained intact in several places, an architectural solution that seemed more consistent with the stage work.

Grassi’s work on the Roman theatre in Sagunto touched on a subject that often divides archaeologists, architects and conservation experts. Due to the reactions against the new construction that hid the amphitheater, obscuring at the same time the view of the city from it, the works stopped for a long time. However, the Grassi claimed that: ”we built a theatre in the way of the Romans and we did it with means: our culture and the eyes of our time. This is exactly how a Roman theatre could be built today.” [1] For the architect, there is no difference between reconstruction and new construction. Since the relationship with the historical experience is a necessary and unavoidable condition for every project, then all the projects are, for Grassi, reconstruction projects.

Of course, Grassi did not aim to build a project that would be the lesson for all subsequent studies. After all, he himself was never dogmatic with his ideas and adopted doubt as the only creatively acceptable attitude. “To be perfect, without omitting anything that is not self-canceling” [2], he specifically mentions as an epigrammatic phrase for the work of the architect. However, through this project he raised an important question: is there a correct way of intervening in our architectural heritage? In which level, in the end, reaches a reconstruction work and what is the significance of strict historical preservation laws that mainly lead to mimetic reconstruction and thus a mimetic destruction of fragments of the past?

Gadamer argues that “Understanding is to be thought of less as a subjective act than as participating in an event of tradition.” [3] In this sense, Grassi seems to express a broad understanding of tradition. He invokes tradition as a continuum of human coexistence with the built environment within its temporality. His method could be understood as an endless process of understanding the typology and forms of the past, through a repetitive, almost aphasic, construction logic that redefines new meanings, each time creating an invisible grid of tensions.

All Photos © Chen Hao

_

Notes:

1. From Grassi’s interview in Displayer magazine, vol 3/2009.

2. Patestos, K. (1998), “Giorgio Grassi: Texts for Architecture”, Athens: Kastaniotis.

3. Gadamer, H.G. (2004). “Truth and Method”. Trans. J. Weinsheimer, D. G.Marshall. London: Continuum.

Christina Serifi is an architect, researcher and urbanist. She isalso co-founder of TiriLab (Future Architecture Platform Fellow) an initiative which explores multi cultural heritage related to techniques, technologies and culture specifics from communities in northern Greece. Christina is associate researcher in Terreform, where she has coordinated various publications regrading indigenous knowledge, alternative educational models and self sufficiency. Her work investigates forms, collective memories, typologies and local practices, focusingon urbanfragments, in-between spaces, as well as osculation of architectural and social space, Christina has been awarded with the Fulbright fellowship and Urban Design Award ’14 from CCNY. | Photo © Norman Possselt