Agriculture And Architecture: Saving Spaceship Earth

Sonja Dragović takes a closer look at the topics raised and conversations inspired by the exhibition Agriculture and Architecture: Taking the Country’s Side at the Lisbon Architecture Trienniale.

Agriculture and Architecture: Taking the Country’s Side exhibition is on display at the Garagem SulI until February 16. | Photo via Lisbon Architecture Triennale

The fifth edition of the Lisbon Architecture Triennale, entitled The Poetics of Reason and curated by the team led by architect and theorist Éric Lapierre, was opened in October 2019. Aimed at approaching, examining and presenting architectural rationality today from different vantage point, the program offered five main exhibitions: Economy of Means, curated by Lapierre himself, Agriculture and Architecture: Taking the Country’s Side, curated by philosopher and historian Sébastien Marot, Natural Beauty by Laurent Esmilaire and Tristan Chadney,What is Ornament? by Ambra Fabi and Giovanni Piovene and Inner Space by Mariabruna Fabrizi and Fosco Lucarelli. Related events – workshops, lectures, discussions – have been organized throughout the last fall, culminating with the end-of-November Talk, Talk, Talk: a three-day conference that brought academics, architects, designers and activists together for a weekend of lively conversation at the Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation.

Talk, Talk, Talk: Sébastien Marot, curator of the exhibition. | Photo via Lisbon Architecture Triennale

The first day of talks was devoted to the topics raised by the exhibition Agriculture and Architecture: Taking the Country’s Side, the only one from the Triennale’s program still on display (at the Garagem SulI, until February 16). The exhibition strives to be practical, to find answers to contemporary climate change challenges by reconnecting and reconciling agriculture and architecture and harnessing the knowledge resulting from this reunion. The questions emerging from such goal – about the realities of industrial development, the future of metropolis, the complexities of food production, the ethics of design – were some of those unpacked and discussed at the Talk, Talk, Talk conference by the exhibition curator Sébastien Marot, environmental designer and ecological educator David Holmgren, architects and writers Carolyn Steel and Colin Moorcraft, philosopher Joëlle Zask and their eager audience.

David Holmgren, one of the founders of the permaculture concept, joined the conference via Skype. | Photo by Sonja Dragović

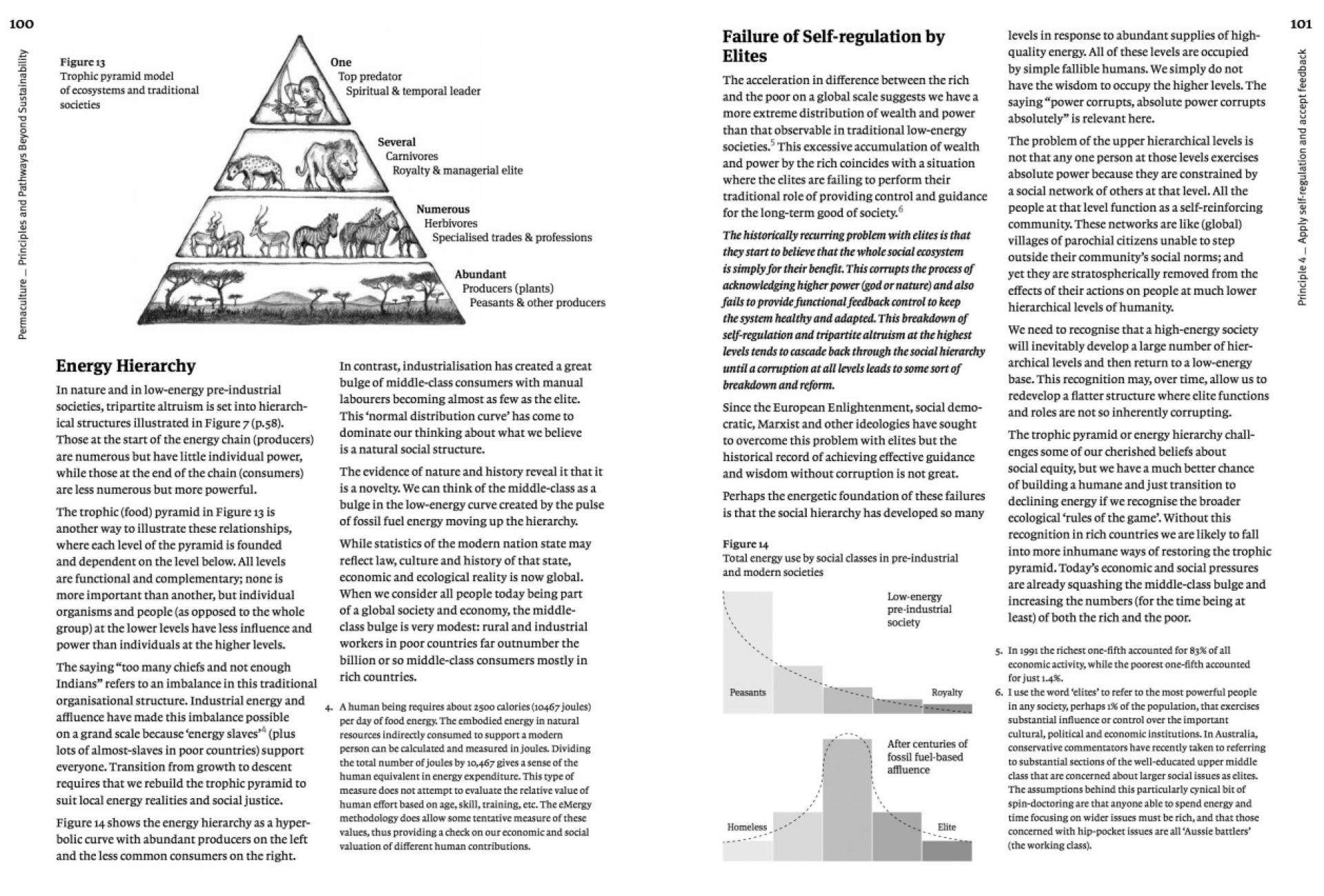

David Holmgren joined the conference from Australia, just before the dawn; via Skype, we witnessed the sun rising on the other side of Earth as the evening conference in Lisbon was coming to a close. Best known as the co-founder of the permaculture concept, he described the way in which this idea that took shape in the mid-1970s at the University of Tasmania and at Mount Wellington, “at the sharp edge between the civilization and wilderness”, gained ground around the world and made it possible to imagine “climate chaos resistant design” on a global scale. Holmgren’s thinking and practice were inspired by indigenous practices in land use and agriculture, which understood and utilized ecosystems’ natural resilience and evolution. He emphasized the importance of dealing with the environmental crisis in large cities by upholding the practical thread of action and criticized the apathetic acceptance of the inevitability of status quo. For anyone interested in learning more about permaculture, his works Permaculture: Principles and Pathways Beyond Sustainability (2002) and RetroSuburbia: The Downshifter’s Guide to a Resilient Future (2018) will be a great start.

From Holmgren’s book on permaculture. | Excerpt via Holmgren Design

Carolyn Steel, British architect, author of Hungry City: How Food Shapes Our Lives (2008) and leading thinker on food and cities, pointed out the “urban paradox” of people living in urban areas, thinking of themselves as urban – detached from the countryside, but still depending on land and not grasping the true value of food. According to her, evolving technologies of feeding ourselves might make it appear that the food is simple – too simple to worry about in our digital age. However, the fact that the complexity is obscured doesn’t mean it isn’t there. Steel calls the world shaped by the current food systems Sitopia (from Greek sitos, food and topos, place). She advocates for changing the ways in which we perceive food supply and for becoming more self-reliant and community-oriented in food production and consumption: “To build a better society, we have to embrace this complexity.” Steel’s recently written for Architectuul on the topic of shaping our future through food.

Forthcoming book by Carolyn Steel. | Photo via Amazon.com

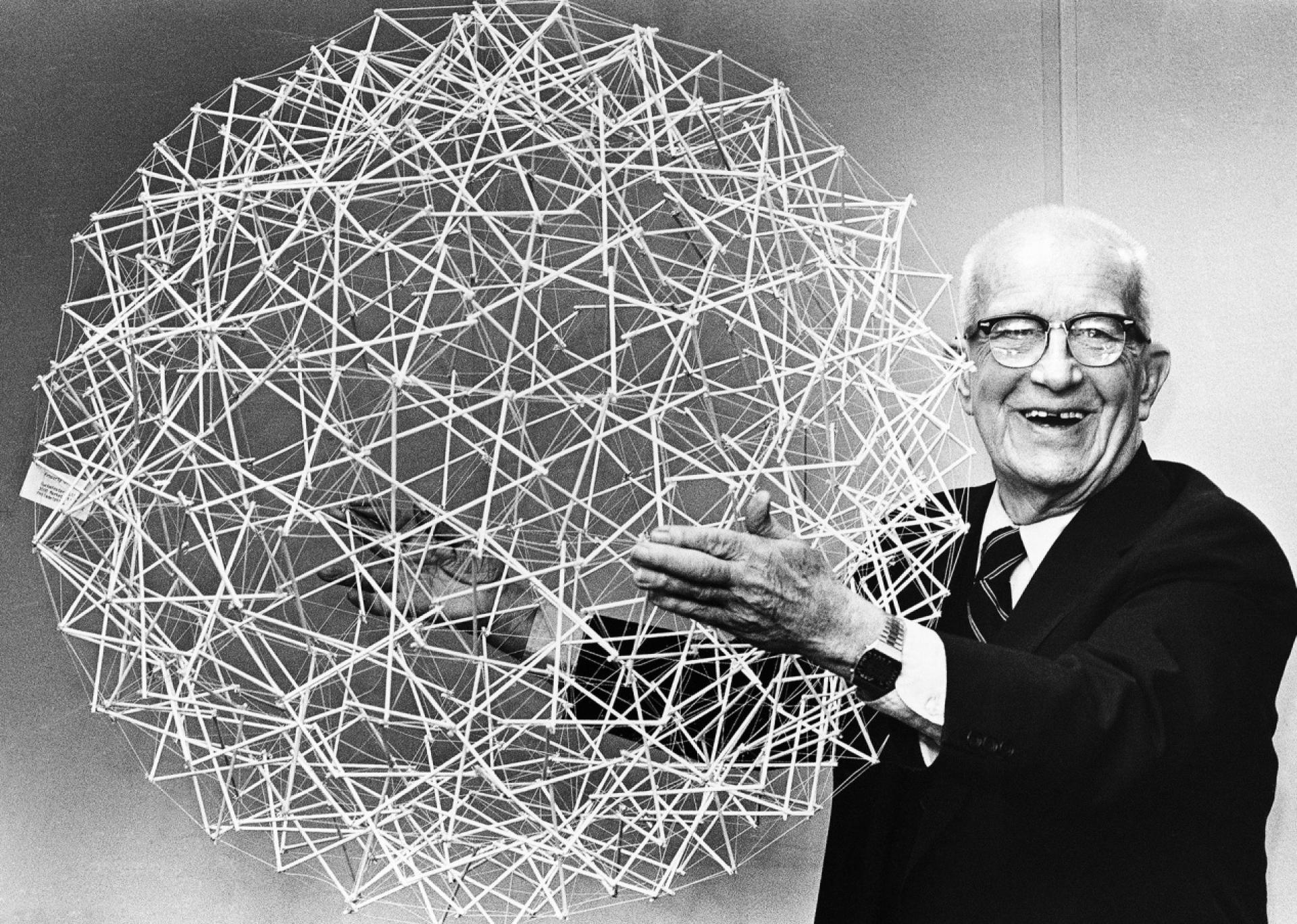

Steel’s argument that food production should be brought closer to home was affirmed by Colin Moorcraft, British architect and writer on environmental affairs, author of Designing for Survival (Architectural Design, 1972). He reminded the audience of the work of R. Buckminster Fuller, an architect and inventor who in 1969, just after the world has for the first time ever seen the photograph of Earth from space, had published an Operational Manual for Spaceship Earth. In it, Fuller wrote: “We are all astronauts and ours is a vehicle that requires maintenance, and that will cease to function if it’s not kept in good order.” He was one of the pioneers shaping the new global awareness, making it clear that we’re all in this together; the other key figures in this movement were, according to Moorcraft, scientists Ludwig von Bertalanffly, Howard Odum and Eugene Odum and the economist Nicholas Georgescu-Roegen.

Colin Moorcraft at Talk, Talk, Talk: Apollo 8′s greatest legacy - a single photograph of home. Sent to examine the Moon, humans instead discovered Earth. | Photo by Sonja Dragović

They contributed towards understanding and defining the interdependence between ecosystems, Earth’s resources and humans. In the beginning of 1970s, they have warned the humanity against the extensive use of fossil fuels and mineral resources – these warnings were outlined in Moorcraft’s Designing for Survival in 1972. As we all know, we didn’t listen, and our environment – inseparable, of course, from our communities – suffers the consequences. What we must do to mitigate these effects and improve our situation, Moorcraft advises, is bring the countryside into the city and design for agriculture to become an integral part of urban experience: “Architecture-and-agriculture is of central importance for improving the prospects of future generations of Spaceship passengers”, he concludes.

Buckminster Fuller: Making the world’s available resources serve one hundred percent of an exploding population can only be accomplished by a boldly accelerated design revolution. | Quote and photo via pbs.org

The final talk of the evening was given by Joëlle Zask, French philosopher, author of La Démocratie aux champs (2016). She introduced the origins of democracy as “peasant affair”, starting in the fields rather than in cities. When the separation of food production from intellectual labor occurred, taking care of the body (the countryside) was separated from taking care of the soul (the city); the body was deemed less important. This separation persists, and Zask argues that repairing the link between architecture and agriculture is important because it would mean rediscovering and repairing this connection, entering the discussion with the soil, cultivating relationship with the nature, and developing oneself. Finally, it would lead to a more democratic society.

Talks after the talks: discussion with the audience at Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation. | Photo via Lisbon Architecture Triennale

Presentations by these four speakers, building upon topics outlined in the Agriculture and Architecture: Taking the Country’s Side exhibition, inspired an evening of lively discussion that spilled over into the next two days of the Talk, Talk, Talk conference. Now, this practical and hopeful stance towards the worrisome state of our environment should spill over into a bolder future action countering climate change. Our Spaceship needs repairs – and repairing the relationship between agriculture and architecture could be a great new start.