FOMA 16: Romanian Coastland

FOMA goes back to Romania. Miruna Dunu is exploring the seaside architecture on the Romanian Black Sea coast. She is passionate about collecting postcards that brought her to the investigation of the complex case study of the socialist leisure facilities between 1960s and 1980s. Her Forgotten Masterpieces are revealing the vast political mechanism, the social discrimination and the hyper real narrative of the seaside holiday architecture, the forgotten promised paradise.

Venus resort beach. | Postcard author’s collection, photo by Hedy Löffler, 1980

Historically a privilege of the aristocracy, leisure only became accessible to the masses in the 20th Century. In the particular case of seaside leisure, it was a gradual process that combined ideological aspects on the one hand, such as health pursuits and the creation of the modern man, and more practical considerations on the other hand, like the new work patterns imposed by the Industrial Revolution. Furthermore, with a working class already on the rise before WW2, state policies for paid workers’ holidays drove leisure and its associated architecture one step further. Making no exception to the established trends, the basis of the Romanian seaside leisure was laid with the emergence of the first treatment facilities in the late 19th Century. In the early 1900s, the first beach cabins appear together with a wooden pavilion of Victorian inspiration, in the old fisherman’s village of Mamaia.

Royal Palace of Mamaia by Mario Stoppa. | Image via adevarul.ro

The inter-war period marked a significant increase in the emergence of seaside facilities. Once reserved for the wealthy few or merely a contemplative retreat for romantic flâneurs, the coastal area became a popular destination for fashionable activities like water sports and sun-bathing. The architecture would reflect the novel lifestyle, turning into a breeding ground for spatial experiments and typologies that would hardly belong to the urban setting.

Despite the gradual and relative democratisation of the seaside developments, the aristocracy’s traditional access to the coastal retreat facilities remained prominent, especially in the 1920s. A notable architectural addition of the time is the Royal Palace of Mamaia, completed in 1926. Commissioned by the Romanian royal family, the Neo-Romanian style villa situated in the proximity of the beach is designed by Italian architect Mario Stoppa and consists of lower horizontal volumes with terraces and a watchtower as the main vertical element. The design cleverly combines vernacular elements and textures with the latest technological developments of the time, such as central heating and air conditioning. Unlike the cubist buildings that would become increasingly popular on the coast, the Royal Palace of Mamaia pays homage to the local traditions of the building crafts, exploring the specific architectural expressions of the area.

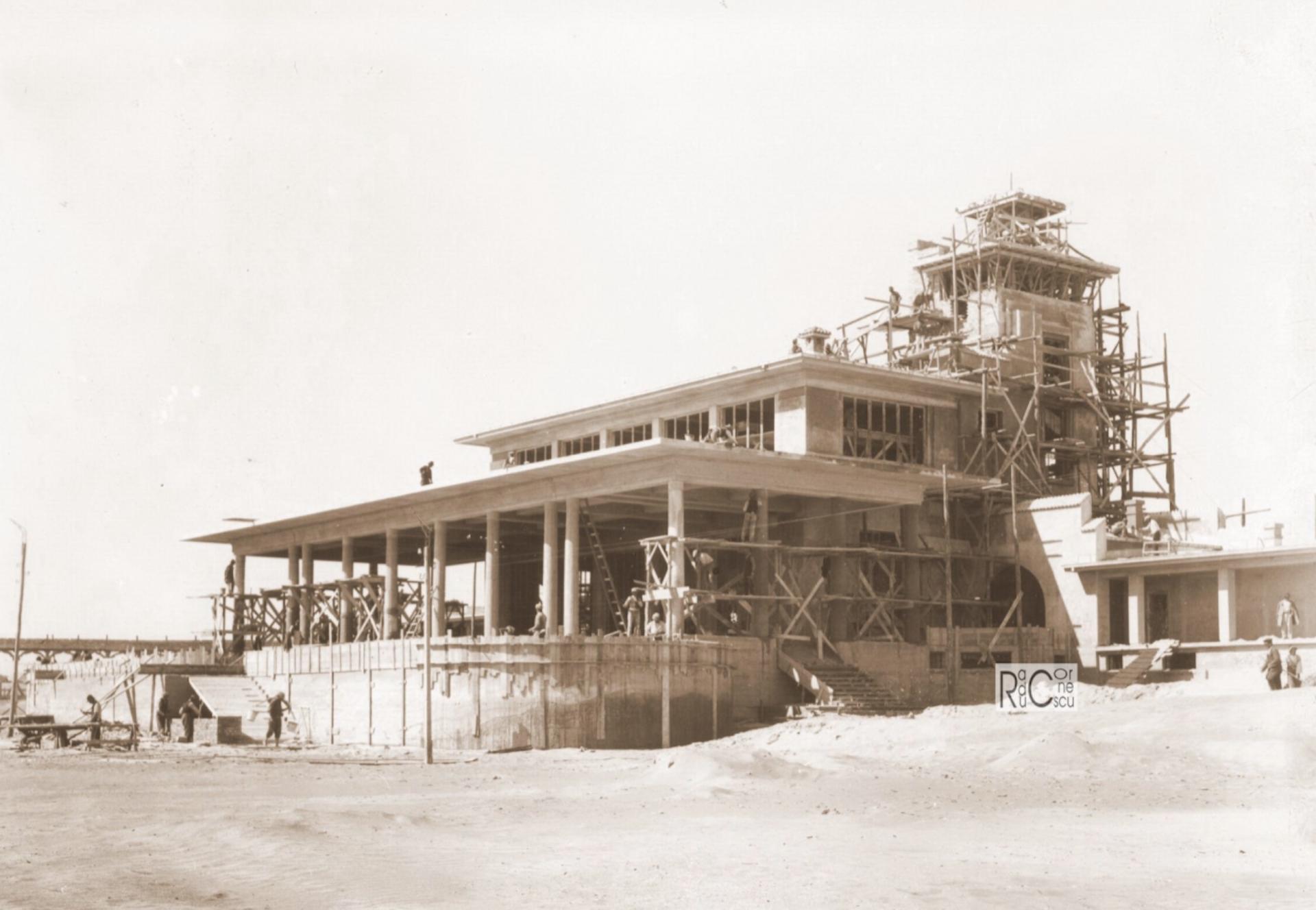

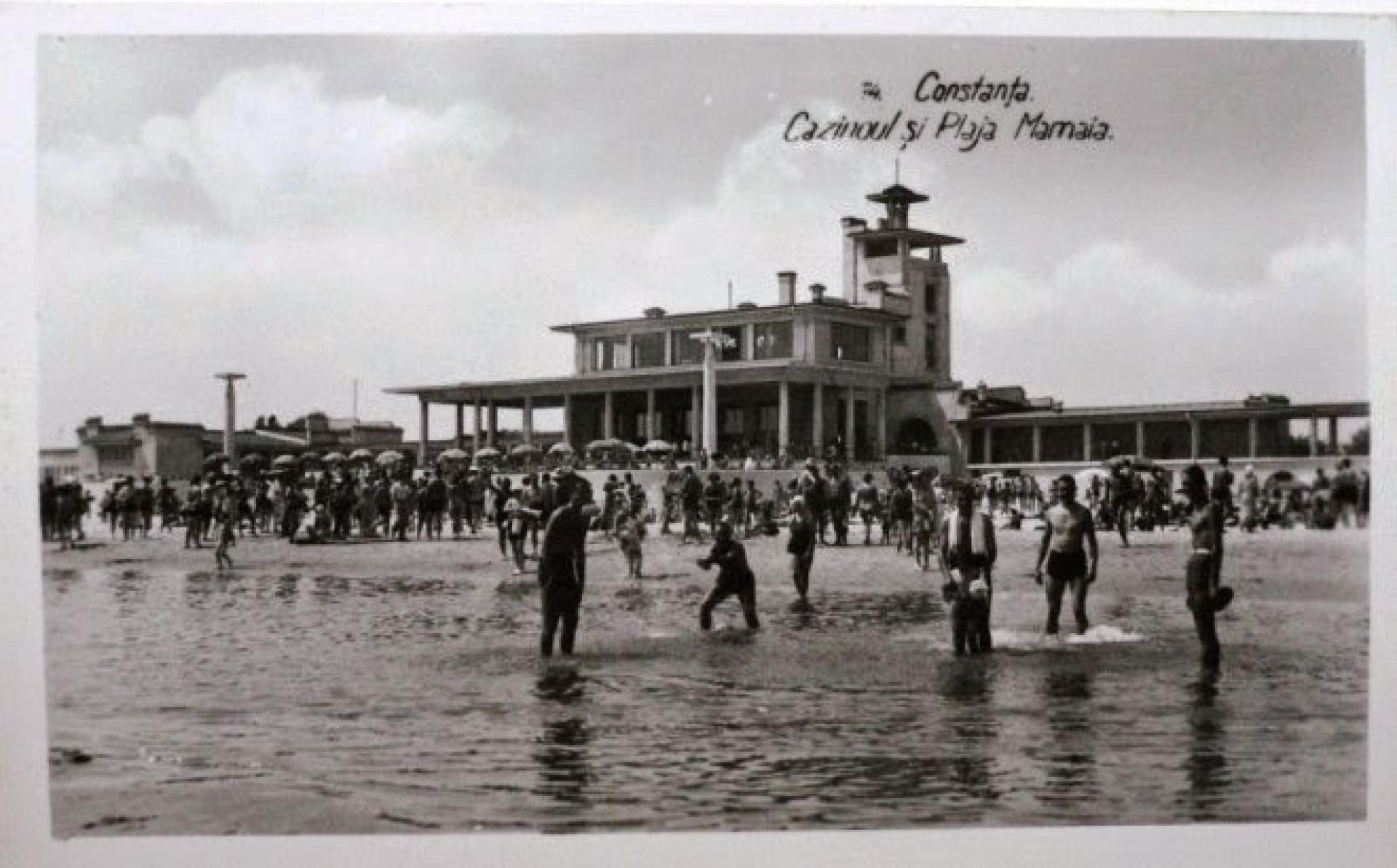

Mamaia Casino under construction in 1934. | Image Radu Cornescu

With the concept of free time on the rise, it wasn’t long before radical spatial experiments appeared on the seaside, driven by both the trends of the latest architectural discourse and the necessities of the new leisure activities. Modernist villas displaying pure geometric structures, unconventionally-shaped bungalows and steamboat-like hotels radically transformed the urban fabric of the resorts, equally reflecting the architects’ and the public’s interest in the contemporary European tendencies. The rising number of tourists stimulated further investments in the seaside’s infrastructure and development. The mid-1930s saw the inauguration of an Art Deco style Casino right at the heart of Mamaia resort. Designed by architect Victor G. Ștephănescu, the building was hosting a restaurant, a dancehall, shops, a police office, telephone booths and the manager’s private suite. Additional beach cabins and a concrete pier with slides, two wharfs for small boats and a terrace-bar at its very end completed the ensemble. The Mamaia Casino complex readily became one of the main attractions on the Romanian coast, hosting thousands of local and foreign visitors each year.

A crowded day at the beach in the late 1930s. | Postcard via radiovacanta.ro

The abrupt transition to communism in the post-war period brought a fundamentally different approach to leisure policies, thus pushing the spatial production in a different direction. Implemented in two stages, the socialist seaside project drove beach tourism to an unprecedented scale.

The vibrant atmosphere on the terrace of the restaurant club Neon in 1957. | Postcard author’s collection, unknown photographer, 1963

The first phase, spanning from 1955 to 1965, focused on leisure as a hygienic retreat, the spatial production consequently reflecting this through the low-rise hotels and spas. Following the international trends, the buildings integrate a functionalist modernist aesthetic achieved through the use of glass, concrete and steel. A notable level of architectural experimentation was involved in the design of clubs and restaurants such as Neon. Elevated on elegant concrete pillars, the attention to detail is visible through the bespoke design of the balustrades, floor-tiling and concrete shell roof.

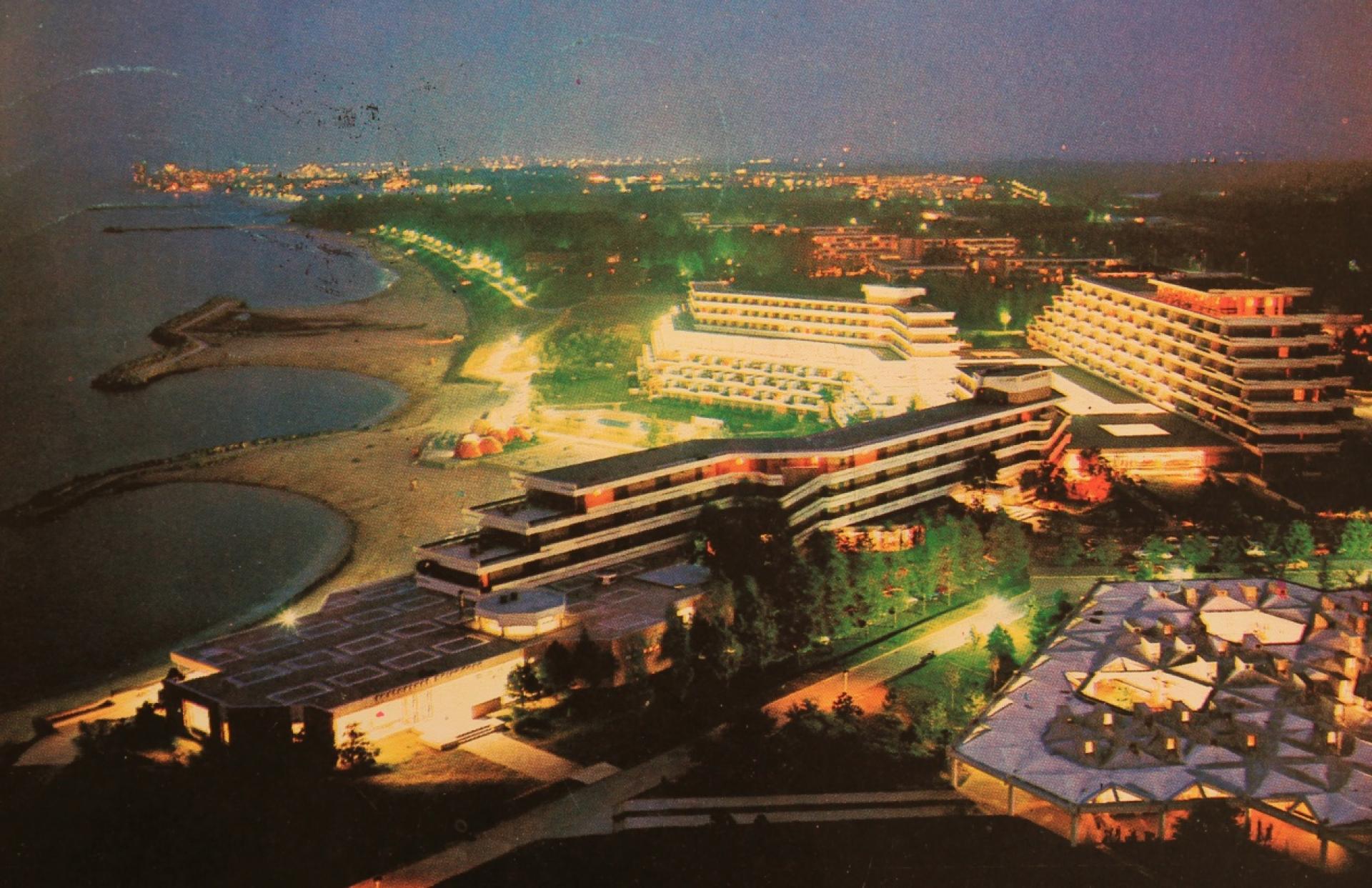

While the first phase intensified the construction of amenities in existing beach towns, the second phase of the seaside development consisted of erecting a series of resorts ex-nihilo. Fuelled by both the public success of the first stage and an extended political agenda aimed at attracting foreign tourists, the architecture and urban planning of the new resorts confidently incorporate the augmented scale.

The “futuristic” silhouette of the Amfiteatru-Belvedere-Panoramic ensemble at night, Olimp (1971-1972). | Postcard author’s collection, Al. Florescu, 1974

The environmental impact of this massive intervention is not to be underplayed, with nature being shaped and enhanced in order to fit the ambitious vision of the architects. The cliffs were carved, a rich natural forest was in part cut down and artificial lakes completed a highly engineered landscape. However, architects strived to incorporate the natural features of the site into their designs. Although the resorts were in certain cases filled with standard boxy high- and low-rise hotels following the same blueprints, two developments stand out for their tailored response to the site conditions. The Amfiteatru-Belvedere-Panoramic ensemble integrates public spaces and other loisir amenities within the actual hotel buildings, merging vertical and horizontal circulation through a series of terraces and wide flights of stairs

Spectacular views from every angle of Amfiteatru-Belvedere-Panoramic. | Postcard from author’s collection, photo by Al. Florescu, 1974

The Aurora resort consists of a series of hotels with a distinctive silhouette that merges modernist pure geometric shapes with organic angulations and layouts that create semi-enclosed spaces filled with vegetation. The architects’ interest in the contemporary (western) discourse becomes apparent in these interventions and echoes Romania’s relative political openness of the early 1970’s. The construction pace slowed down with the last additions to the socialist coastal development made in the late 1970s. The austerity of the following decade entailed a significant cut down on the state funding for the seaside tourism. Today, a vast majority of the socialist buildings are still standing and largely operated, be them poorly maintained or carefully refurbished. However, the chaotic privatisation policies following the communist downfall resulted in a fragmented landscape that renders the modernist-inspiration layout almost illegible.

The distinctive silhouette of the hotels in Aurora resort (1972). | Postcard via sanuuitam.blogspot.ro, photographer C. Vladu, 1975

Although benefitting from a superior architectural quality when compared to the mass housing developments across the country, the seaside project consistently acted as a microcosm reflecting though its spatiality the broader Romanian socio-political reality, from cultural experimentation and dictatorial control to turbulent transition to free-market economy. In this sense, it is a typical example of how an exceptional sample can paint a rather accurate picture of the whole, if looked at in all its complexity.

A development of an unprecedented scale in Mamaia resort | Postcard from the author’s collection, photographer D. Bădescu, 1970

Notes

Popescu, C. (2014). An Effective Mechanic: the Romanian Seaside in the Socialist Period

Miruna Dunu is a visual designer with an architectural background. She graduated with a Bachelor degree in Architecture (2013) with First Class Honours from the University of Manchester, United Kingdom, and a Master of Arts in Information Design (2017) from the Design Academy Eindhoven, Netherlands. She worked in architecture and in theatre, both fields greatly influencing her work. She expressed her passion for space and visuality through her first film Coastland.