FOMA 24: Towards A Certain Spanish Modernity

Carlos Traspaderne’s FOMA presents Antonio Lamela’s architectures with the photographic overview on Lamela’s Forgotten Masterpieces.

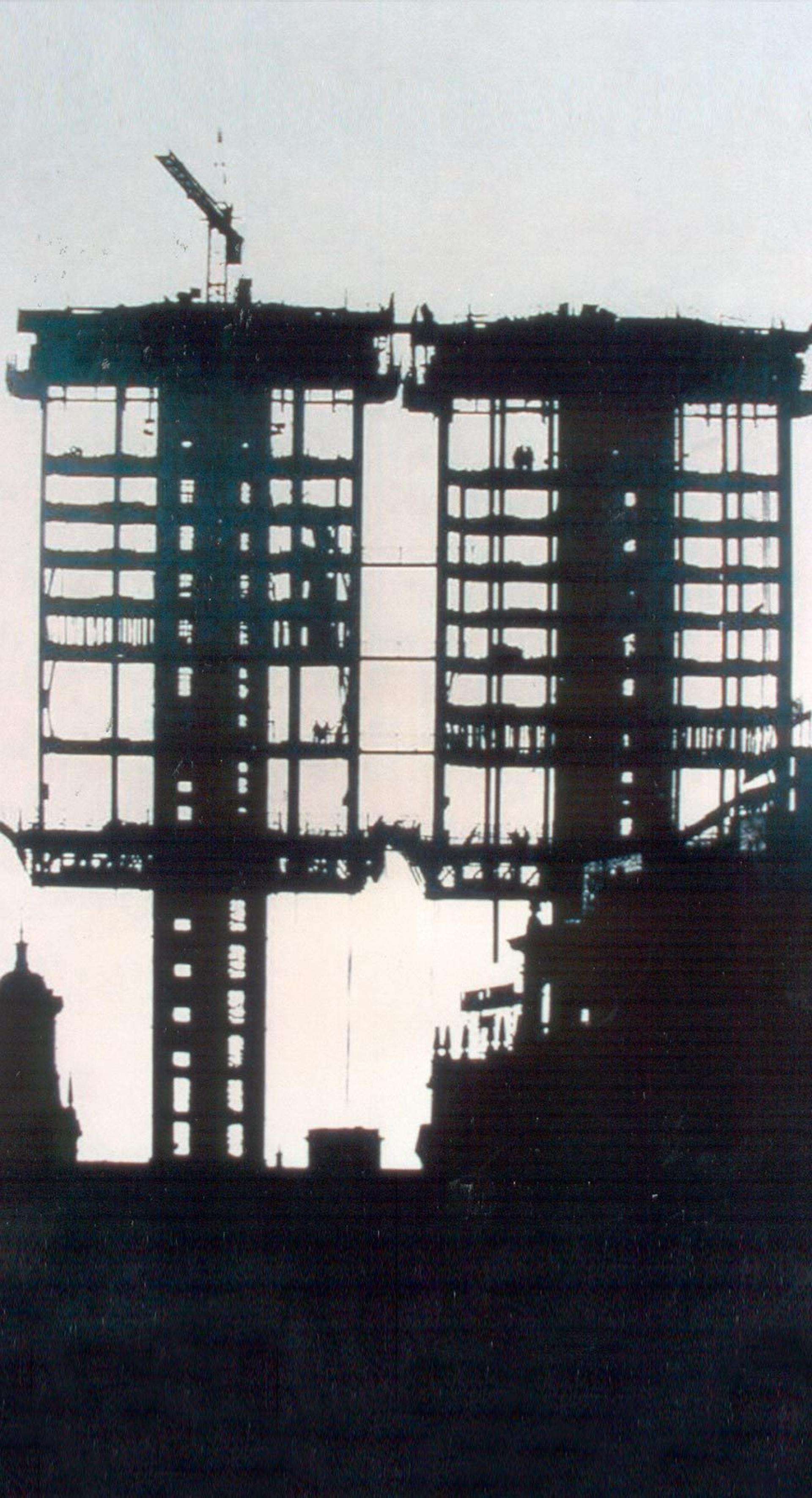

In order from left to right: Amador Lamela (Antonio’s brother), Antonio Lamela, Rudy Fliterman and José Veiga in front of the Colon Towers construction in Madrid. | Photo via Metalocus

Antonio Lamela (Madrid, 1926-2017) is a unique, almost heroic figure of the Spanish architectural scene of the second half of the 20th century. His determination to introduce the latest construction innovations in the country, without ties to schools or trends, distinguishes him from the post-war generation, divided between triumphant historicism and a certain elitist vanguard. A visionary individualism seems to have eclipsed his figure, which deserves to be claimed by his keen perception of how his country’s present and future should be.

Colon Towers were considered as the building with the most advanced construction building technology up to 1975. | Photo © Estudio Lamela

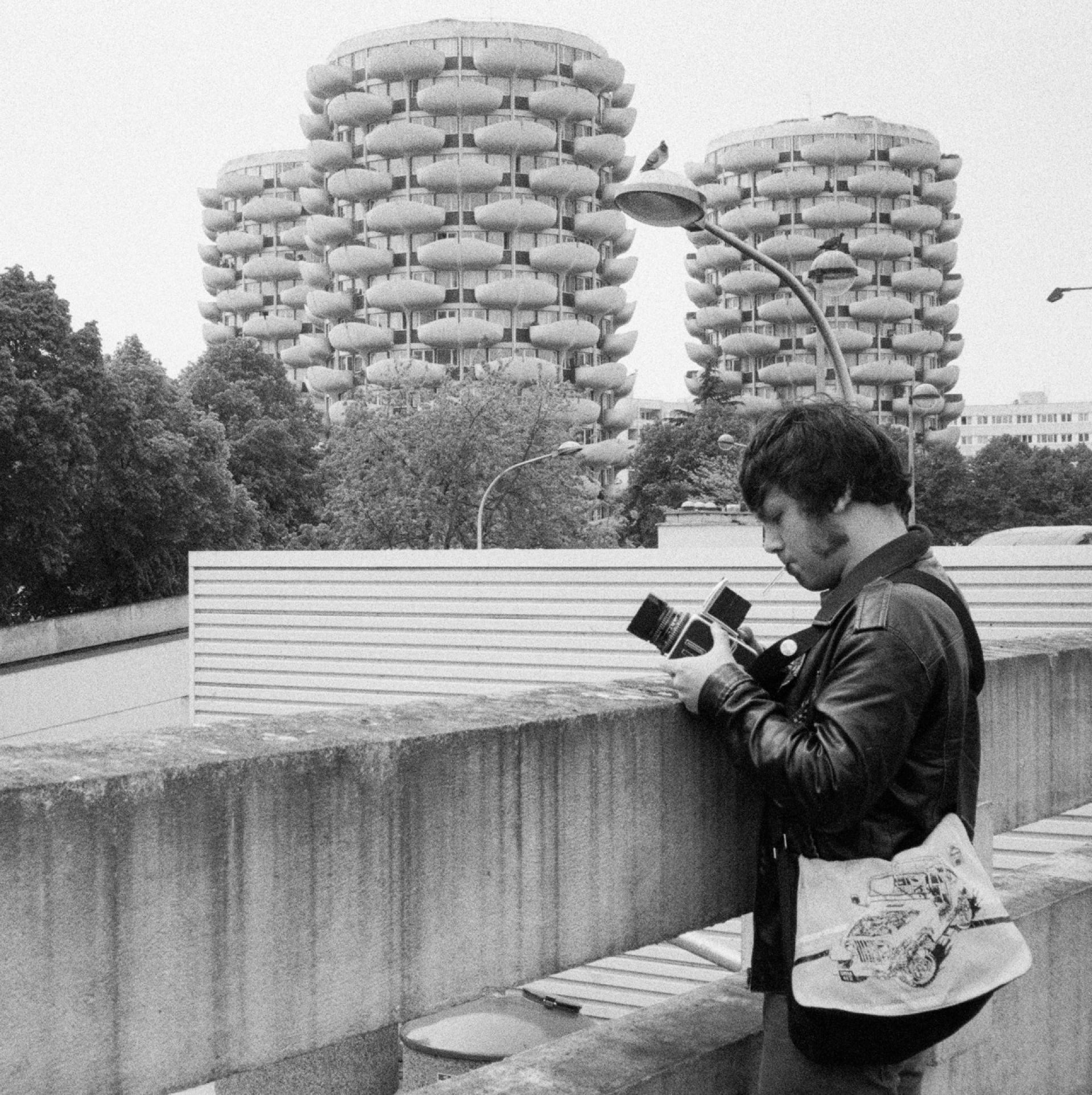

The intention of this article is not to tell a purely architectural narrative of his work, but to paint a visual perspective of his career and what it meant as a transformation of the Spanish capital, represented in its first moment in Madrid, almost completely conserved since its construction. These buildings I have portrayed with my Hasselblad 500 C/M analog camera, almost contemporary to these constructions that paved a new way of understanding architecture in Spain.

The work that inaugurates Lamela’s ambitious career is the O’Donnell 33 building. Initiated in 1956 and erected on a street of Madrid that was at the time divided between the precarious and the deserted, it immediately became a landmark of modernity in a country that was still dormant by the post-war dictatorship. His innovations ranged from the inclusion of a garage (at a time when there were nearly no roads), centralized air-conditioning, to the mosaic-clad surfaces that fill its recessed narrow facade, playing with the staggered plastic surfaces, to the play of light and shadow cast by the balconies overlooking the street. This building, apart from a display of his style and taste, became the home of the architect himself.

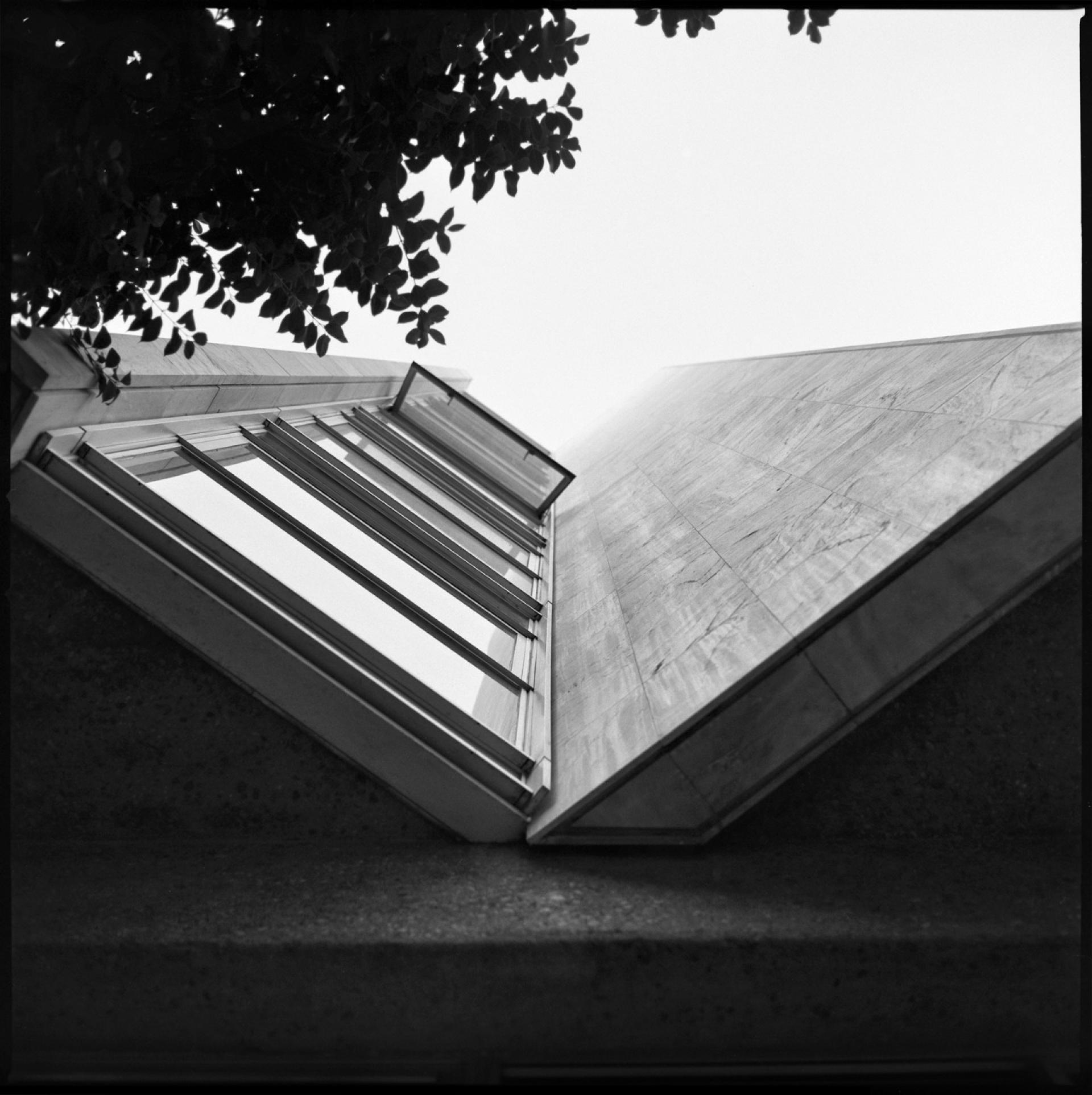

On the opposite sidewalk, the O’Donnell 34 office building became Lamela’s headquarters upon its completion in 1964. Lamela returns to play with the staggering zigzag rhythm, with lights and shadows. This time he orients them diagonally Tod the road, instead of perpendicularly. He also accentuates the facade’s vertical elements with a contrast of dark glass trimmings and snow-white marble bands, a play of variation that seems to pounce on the pedestrian passing under this corner building, projected onto the street like the bow of a boat.

The white marble cladding was also to envelope the Centro Princesa from the same period. A gigantic complex of offices and apartments dominated by the slender figure of a luxury hotel, modelled by continuous bands of windows that repeat over the white lines, like an eternal pentagram in its height. Below, the covered entryways on the ground floor form a hexagonal block, all these geometries competing to form a small fortified city, dominated by its special tower of homage; a fortress closing in on itself, independent from its surroundings.

The Pirámide building is located in the financial district of Madrid, on Paseo de la Castellana. Lamela goes back to the reinforced look and the play of tensions between open and closed, light and dark, but upon a pyramid trunk’s figure that shapes an office building into a modern ziggurat, its skin of shimmery bronze. The contrast now resides between its basic figure and the hollow concaves of the windows, between the primitive and the most rabid modernity of the seventies.

To these four examples prior to Franco’s death and the end of dictatorship, I will add another aspect of his achievement. Something that’s hidden by the genius of his great works such as the Colon Towers and succeeding projects, far from the bustling capital, but another symptom of that search for modernity: the publicity of tourism.

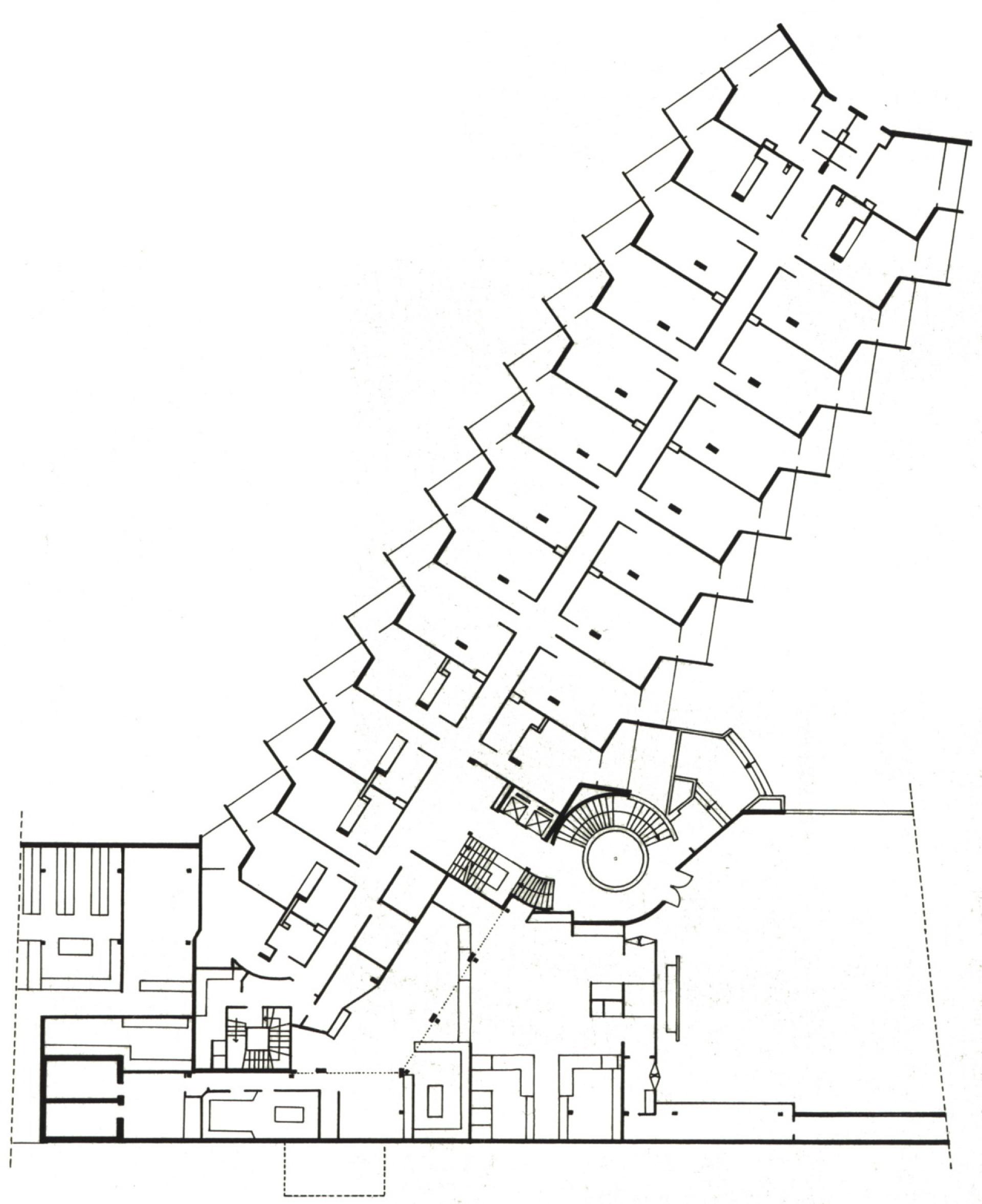

Torremolinos, on the southern coast of Spain, was at the beginning of the sixties, the epicenter of tourism and the point of entry for international visitors from all over the world. This was where Lamela would experiment with Carabelas hotel, designing a herringbone layout that guaranteed light to every balcony and room while providing them with shade by the projected panels. In turn, the dynamism of the facade was guaranteed by the play of surface and concave, giving a further twist to his taste for zigzagging surfaces. We can no longer appreciate the subtlety of this design rather that in old photographs, as the complex was demolished a few years ago by disregard and ignorance.

Rooms shaped a block set parallel to the road, seeking views of the garden and a southeast orientation, with large private balconies. | Photo © Estudio Lamela

A somber ending that reminds us of the necessity to protect Forgotten Masterpieces of this period, especially those of Antonio Lamela, a figure that deserves to be claimed a year after his decease as the creator of a certain Spanish modernity: its modernity.

Carlos Traspaderne (Logroño, 1983) is a Spanish photographer who specializes in historic photography. He only shoots with film cameras. Check his newest shoots at his blog Brutalismus and Ariadna en sitios. Photo © Adriana Bañares