FOMA 15: In Search Of A Never Written Library

For most of the conscious part of his adult life, Dániel Kovács had been writing and collecting texts about architecture. Mainly in Hungarian, his mother tongue, but, sometimes, in English and occasionally in German and Italian, as these are the languages he more or less understands. And FOMA will this time follow Daniel to Hungary.

A newly renovated glass window from the Holy Cross Church, István Szabó’s own work. | Photo by Dániel Kovács

For a while I’ve been trying to build up a personal library on Hungarian architecture, mostly of texts written by others, as a matter of fact. Many books have been about this. Some are interesting for their authors: Edwin Heathcote, for example, wrote a book about Budapest before he became the architecture critic of the Financial Times. Others are important for their newly expressed viewpoints, like Ákos Moravánszky’s works about the era of the Austro-Hungarian monarchy.

But the texts I own, as history texts in general, have been written (or dictated) by winners. They’re about architects who managed to secure their reputation, engage in public life, secure well-funded public commissions or at least, have a controversial carrier. These texts were mostly written about architects and architecture, that we talked about anyway. Only a very few tries to discover something new, something that no one wrote about before.

A few months back I got a letter from Bratislava. A Slovak architect, Vít Halada was enquiring about some buildings in Budapest by István Szabó, whose life and oeuvre had been the topic of my art history master thesis in 2007. For my biggest surprise, Vito not only knew about Szabó but even visited some of his works, and was compelled by his small Holy Cross church in Táltos utca, Budapest. Especially after ringing the priest’s bell and gaining access to the archives of the parish – an accomplishment I, shamefully, never managed to achieve.

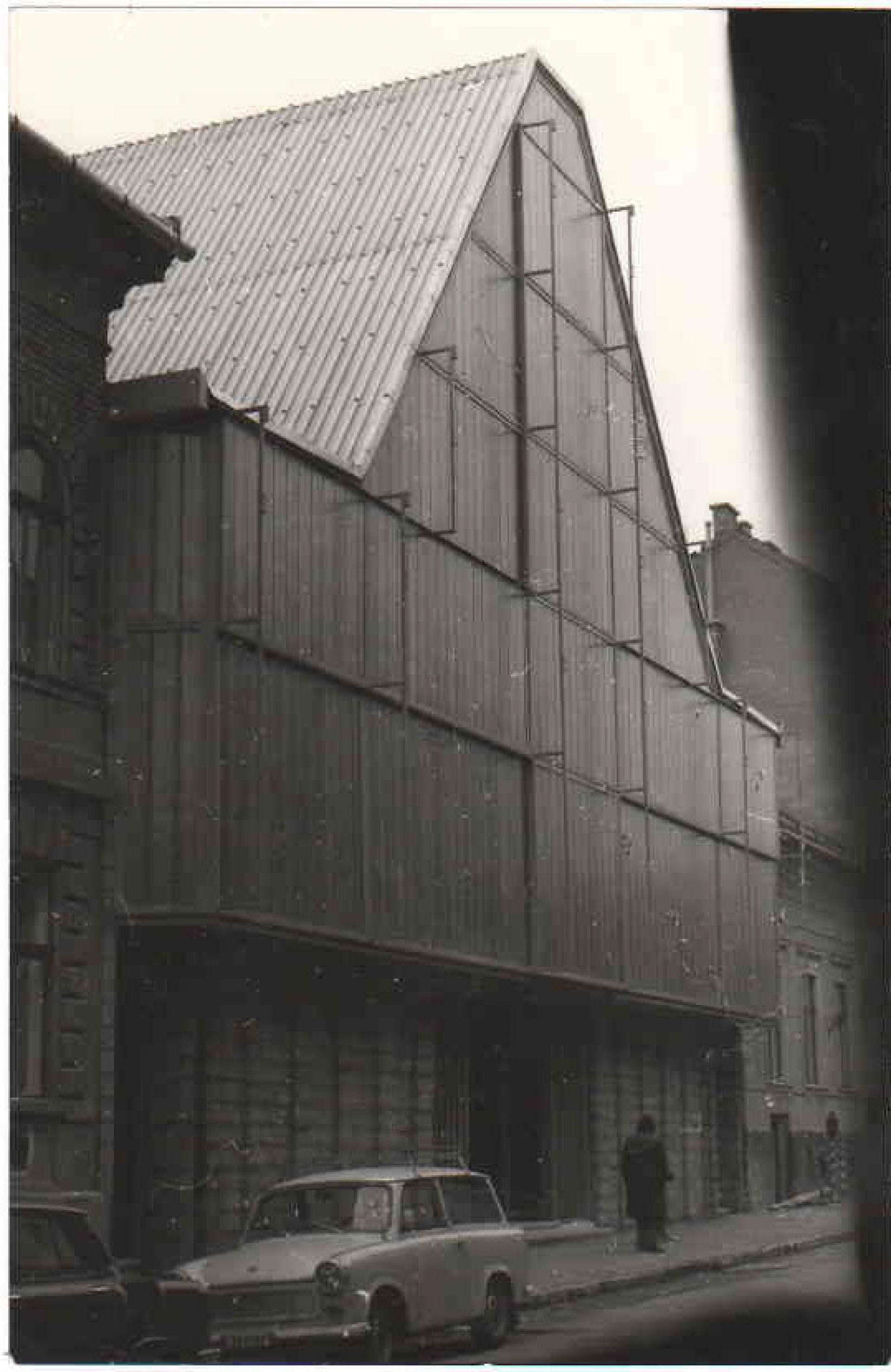

István Szabó’s Holy Cross Church in the original state. | Unknown photographer, photo from the author’s archives

When retiring in 1975, István Szabó was about to enjoy a well-deserved rest after completing numerous public buildings and exhibition pavilions; thankfully, he has always been interested in quick and thrifty problem solving. So when he was approached by the priest of his own parish (he was a practicing Roman Catholic) if he’d design a new church, he did not take too much time for consideration.

Despite knowing that no Catholic church has been built in the capital since the Communist takeover in 1948-1949.

István Szabó’s first church, the All Saints Parish Church of Farkasrét in current state. | Photo by Dániel Kovács

With the backing of an influential ‘Peace Priest’, Imre Bíró, who was also a member of the Parliament and committed to ease relationships between state and church, Szabó managed to design and built a new All Saints Church for the Farkasrét parish. The project was permitted as a reconstruction and extension, but in fact a completely new building was erected on the basement walls of its predecessor. The whole building is constructed of prefab slab elements, used as bricks, having a hollow core filled with concrete. Szabó chose to use this widely available construction material because of the financial constraints, as the whole project was financed by donations – a situation I coined the term Deficit Brutalism for. As construction leader, he also had to count with the fact that the building was going to be erected by volunteer work of the parish members and high schoolars. The interior furniture was also designed by him, just as the glass windows. On the latter he tirelessly worked on until his death in 1988.

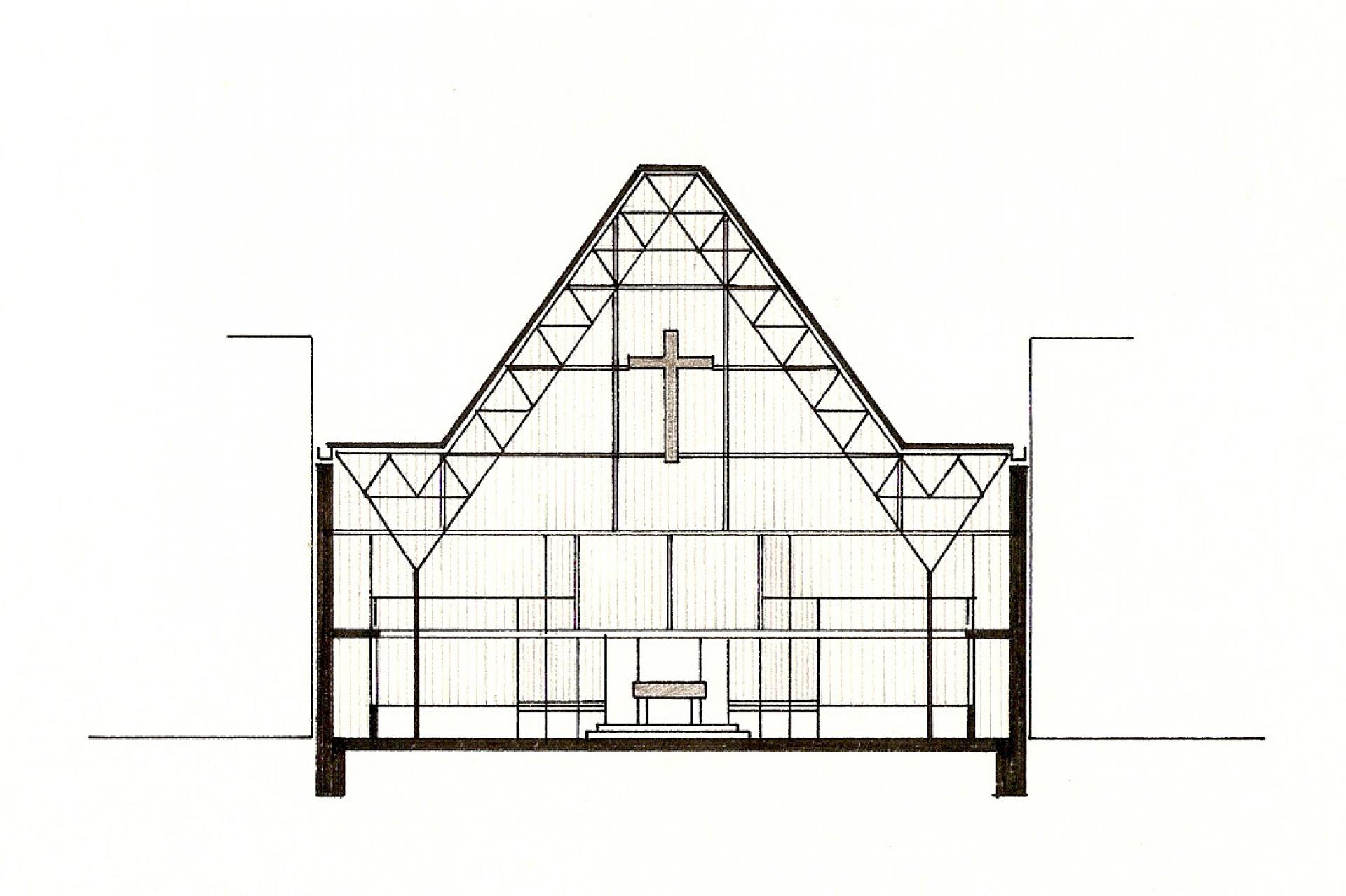

Cross-section of the Holy Cross Church. | Drawing by István Szabó, Hungarian Architecture Museum

The success of this, both Communist Budapest’s and his first church brought a state award, the Miklós Ybl Prize to Szabó – and numerous other commissions. In the last decade of his life, he designed ten more churches and lived to see seven of them being built. The second, the Holy Cross parish church in Táltos utca, Budapest, was erected in 1976-1979, using similar concrete slabs as load-bearing walls and Szabó’s own invention, the KIPSZER spatial grid system as roof structure. But when Vito, my Slovak friend visited the building four decades later, he found an almost entirely different one. The church was renovated a few years ago with government funds: the concrete slab walls were covered with red brick, the industrial glass surfaces changed to commercial glass curtain wall. Most of Szabó’s interior elements and his sculptures were put in storage.

Current state of the Holy Cross Church. | Photo by Dániel Kovács

Vito asked me to prepare a lecture on Szabó’s works and post-war Hungarian architecture. It did not took long to realize how little actual written information I have on Post-War Hungarian architecture – and how hard it is going to get some.

Szabó’s first church, the Farkasrét one, enjoys a protected status since 2011. But most of the era’s other important buildings do not. The former state institution for monument protection currently being under reorganisation and the Hungarian Architecture Museum closed for the public, it is not easy to gain information. This is particularly true when we’re talking about stuff of the seventies and the eighties, as these decades are simply too current for architectural research.

György Kővári’s KÖKI transportation center in the original state. | Unknown photographer

Sadly, we lose valuable buildings each year to year without serious consideration and research. This happened a few years back, when a major work of György Kővári, the Kőbánya-Kispest intermodal station or KÖKI in short, was partially demolished. Kővári is a lesser-known architect who mostly worked in the safe office of the State Railways Company; his chef-d'œuvre, Déli pályaudvar, one of the three main railway stations of Budapest, is a modernist landmark of the capital.

KÖKI transportation center, interior in 2008. | Photo by Dániel Kovács

KÖKI was also well-known, or, more precisely, notorious. Finished in 1980, the building features orange plastic panels, red metal structure and blue signage and furniture system – a clear influence of Piano and Rogers’ Centre Pompidou in Paris. While celebrated in its heydays as a sign of progress, after 1989 and without proper maintenance, KÖKI quickly became a security hazard and fell into disrepair. In the 2000s it was already widely seen as an eyesore, and when demolitions started in 2008 to replace part of the original structure with a new shopping mall, basically nobody cared: a major building of Hungarian postmodern architecture, just like Szabó’s incredible industrial church in Táltos utca, was lost without anyone shedding a tear.

KÖKI transportation center, demolition works in 2008. | Photo by Dániel Kovács

Surprisingly, there are different cases. When the government announced in 2016, that they are going to demolish and replace Csaba Virág’s Power Distribution Center in the castle of Buda, then standing empty for almost a decade, the whole architectural scene started screaming. This building, designed to fit into the small-scale environment of the castle but finished in 1979 with state-of-art glass and metal façade, has always been considered a pioneering hi-tech work – in spite of the obviously and typical low-tech execution. While the public debated whether such a controversial building should be protected or not, professional organizations started to collect signatures, write letters and organized visited tours to the building. The widespread campaign resulted the government to withdraw its original plan about demolition and currently they are planning to restore the edifice.

Current state of Virág’s Power Distribution Center. | Photo by Dániel Kovács

But if this can happen to well-known, centrally located buildings of the era, what’s going to happen with other, lesser known ones? Who is going to research about and engage with the protection of 1980-1990s architecture? A few texts have been written about the buildings above, mostly on Hungarian, but the Farkasrét church was recently included to the great catalogue of the exhibition ‘SOS Brutalism’ by the German Architecture Museum. This is, however, more of an exception than a sign of progress. In such a small market and with basically no institutional background, there is few ongoing research in these topics.

And yet, thankfully, there are always some wide-eyed enthusiasts to endlessly debate regional characteristics… A few years ago with friends we founded the Translations of Modernism collective, or Transmodern in short, as a platform for researchers an enthusiasts interested in post-war Eastern and Central European architecture. On our second conference on Socialist Modernism, held in 2016 in Berlin, we greeted 17 lecturers from 11 countries. Recently, we decided that the next conference topic is Postmodernism in Central and Eastern Europe. The conference takes place in Berlin on 17-19 May 2018.

Sándor Dévényi’s House of Weddings, 1983-1985. | Photo by Dániel Kovács

What am I expecting? The most interesting things to discover. Things, such as Sándor Dévényi’s incredible postmodern buildings, designed and constructed in the 1970s and 80s in a small Hungarian town, Pécs. The House of Weddings, which reuses Romanesque, Baroque and Art Nouveau elements. The Roman Courtyard, which has the most spectacular po-mo ceramic façade I have ever seen. And my personal favorite, the Lightning-struck House, which looks like… Well, guess what.

Sándor Dévényi’s Lightning-struck House, 1978-1985. | Photo by Dániel Kovács

Sándor Dévényi’s Roman Courtyard, 1991. | Photo by Dániel Kovács

I do believe that these interesting buildings with their stories are everywhere. You just need to get to know them, write them down and add them to the library. A library I hope to own once. Not just for myself, but for everyone who shares my belief.

Dániel Kovács is a curator, critic and writer. He received his Master’s in art history at the Eötvös Loránd University of Sciences in 2007. After graduation, he became editor and later editor-in-chief of a Hungarian architecture and design magazine, hg.hu. Since 2010 he’s been a member of board of the Hungarian Contemporary Architecture Center. In 2012-2014 he’d initiated and organized the Budapest chapter of CreativeMornings. In 2014, he co-founded Translations of Modernism, a collective for the better understanding and exposure of post-war Central and Eastern European architecture. He’d written various articles to publications such as ERA21, A10, Octogon, given lectures on Hungarian architecture in Shanghai, Warsaw and Bratislava, and from time to time he manages to write something for Wikipedia. He also published two books on Art Nouveau and art déco architecture, but deep down he’s infatuated with post-war things. Since 2015 he’s been living and working in Berlin. (Photo © Barbara Antal)