Postcards, Propaganda and Fiction

Miruna Dunu has already in FOMA 16 explained about the history of the Romanian seaside architecture. This time she presents her docu-fiction Coastland, which is created entirely out of authentic postcards circulated between early 1960s throughout the late 1980s. The collection, currently counting over 300 pieces, was compiled for the purpose of Miruna’s research. Analysing the dissemination of the architectural imagery through propagandistic means, the postcard becomes the entry point to a politically controlled hyperreal universe.

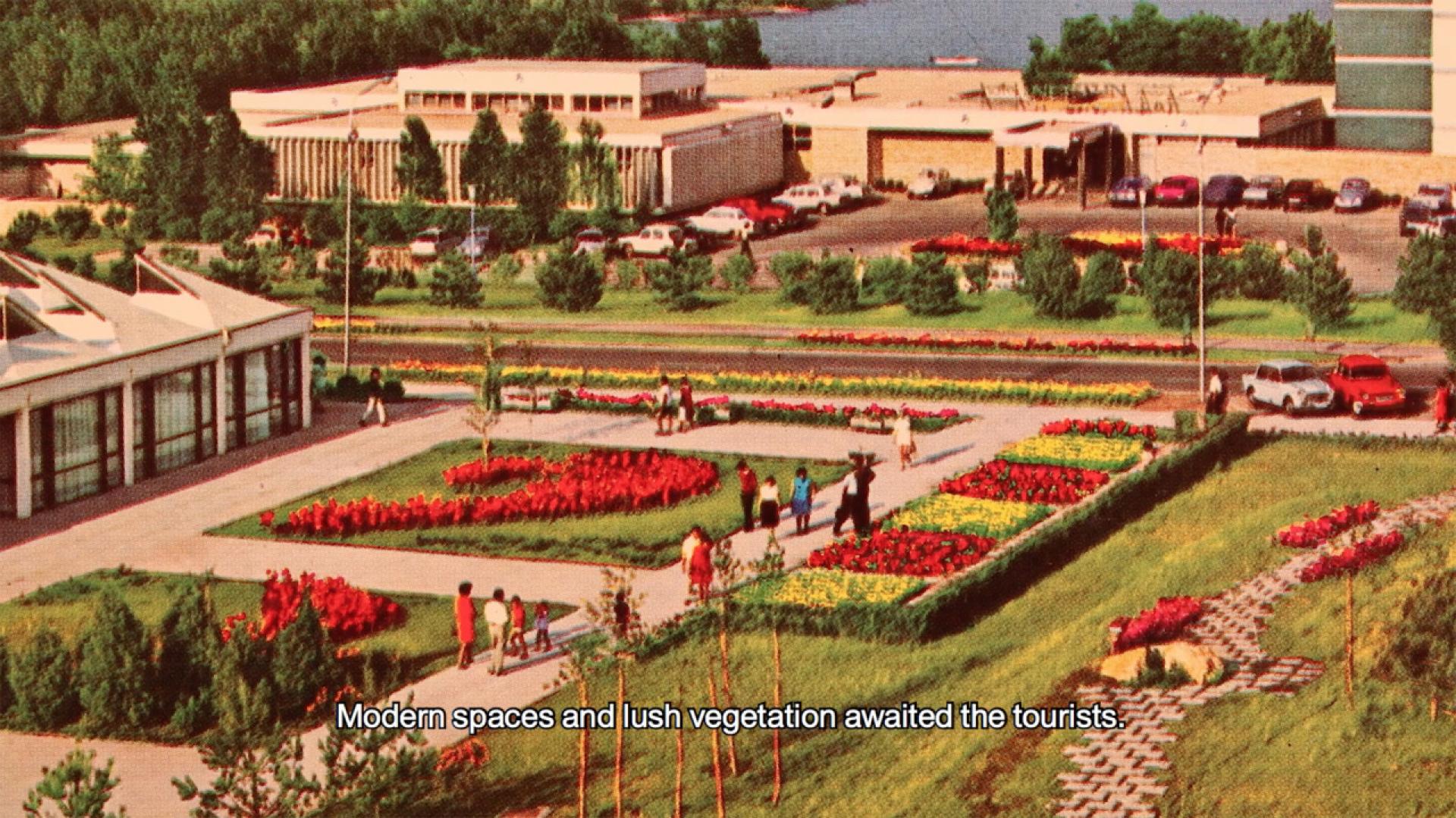

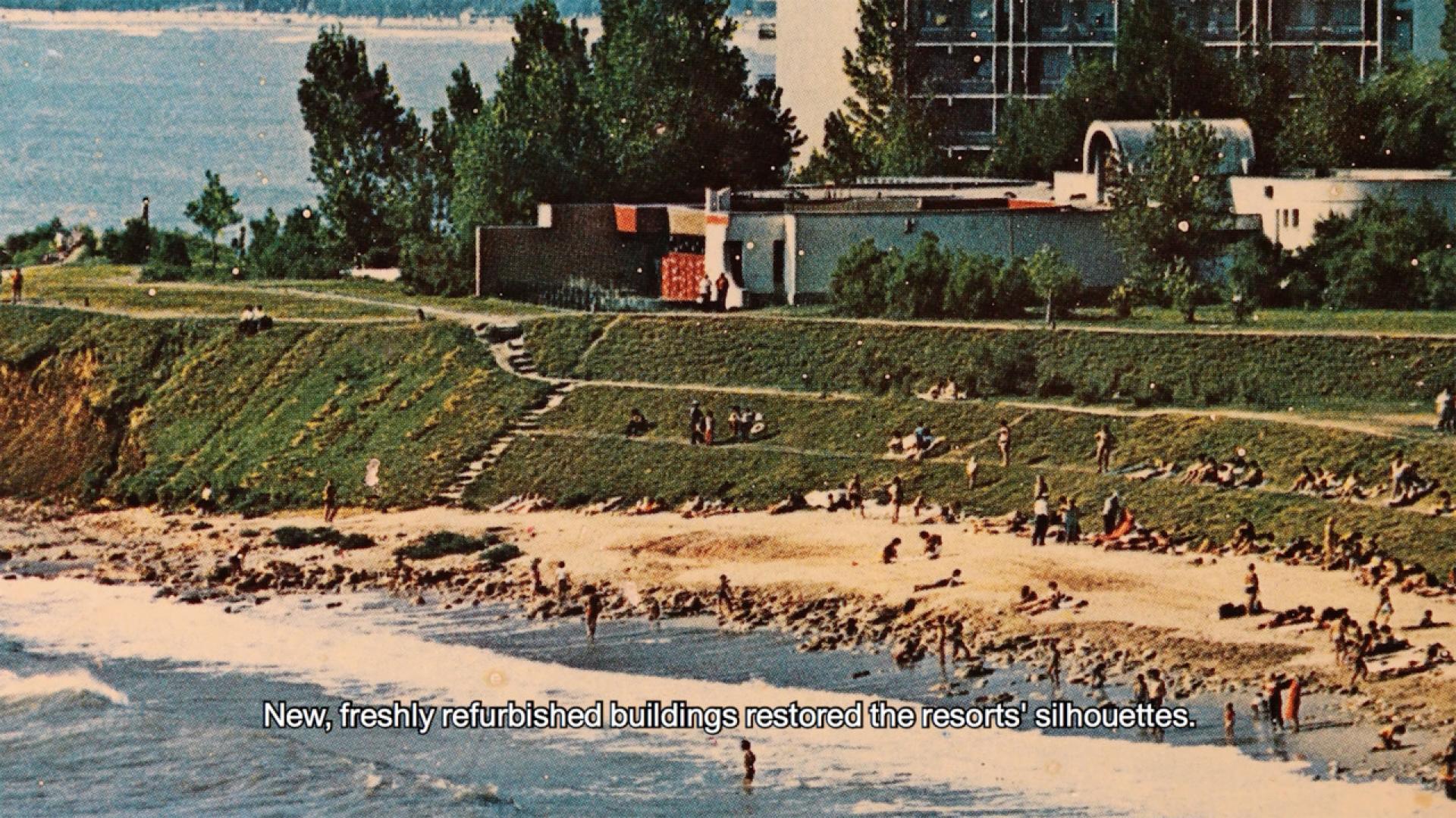

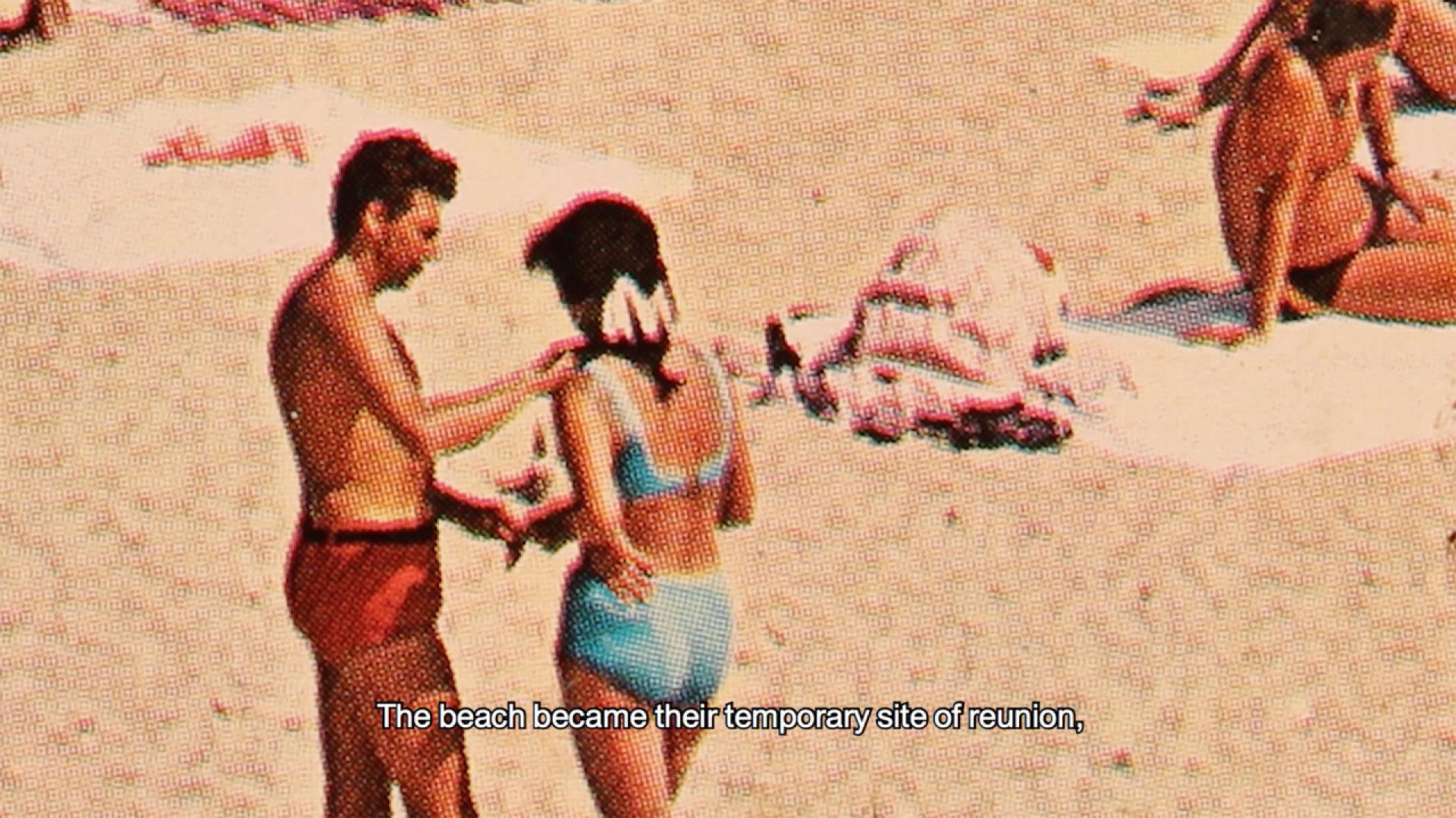

Thousands of alluring images made their way as postcards from the sunny Black Sea coast every summer to parents, friends, lovers, siblings, co-workers, acquaintances, distant relatives, and neighbours. The enticing postcards were capturing fashionable characters enjoying sports activities under the bright skies, with a cutting-edge architecture overseeing the entire scene, as if the modern buildings themselves were the primary condition for such a setting.

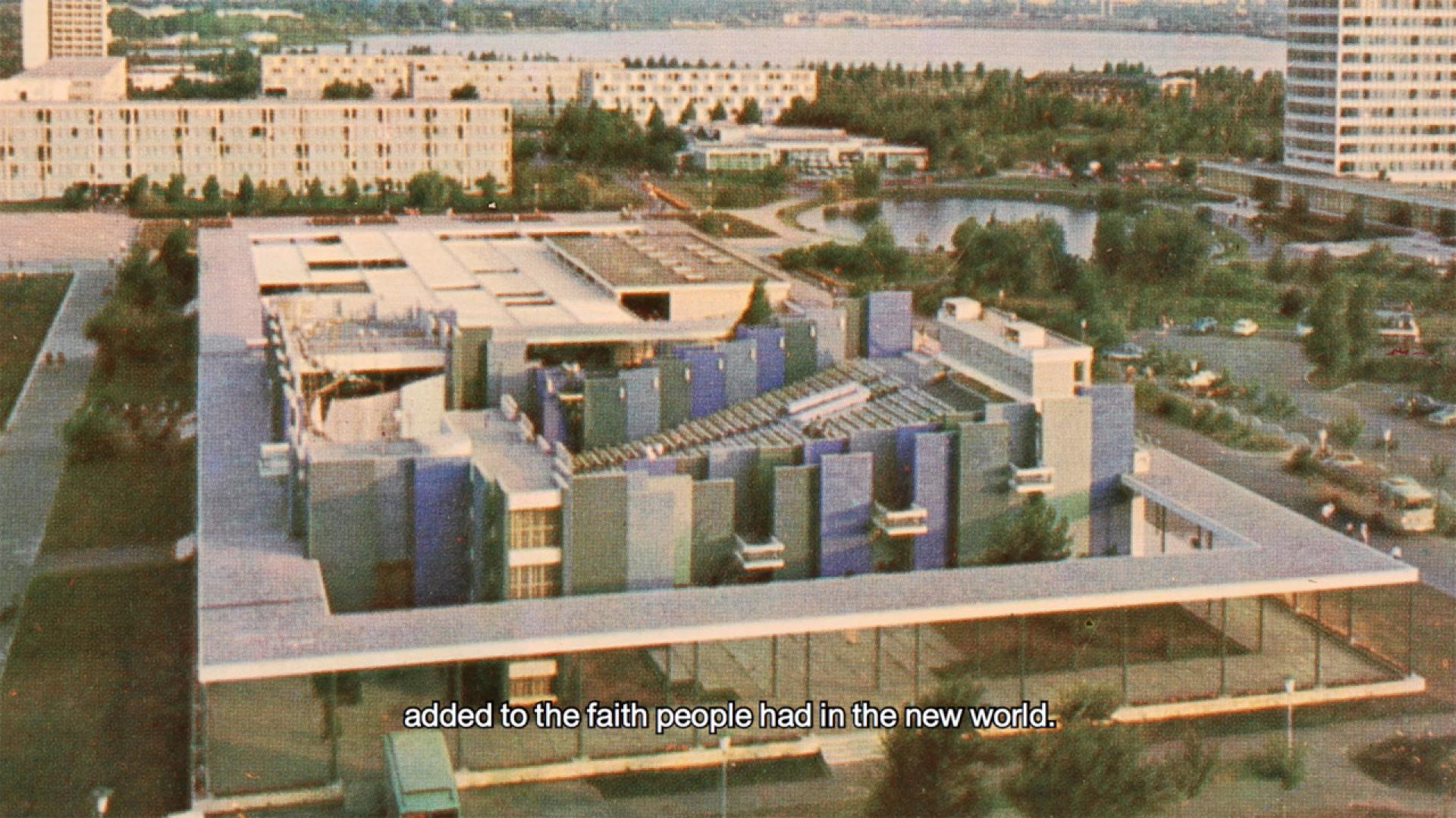

Architecture was instrumental in creating the seaside leisure narrative. Its massive scale, modern design, and superior quality to the architectural production in the rest of the country, ensured propagating the image of a forward-thinking, technologically advanced and prosperous political system.

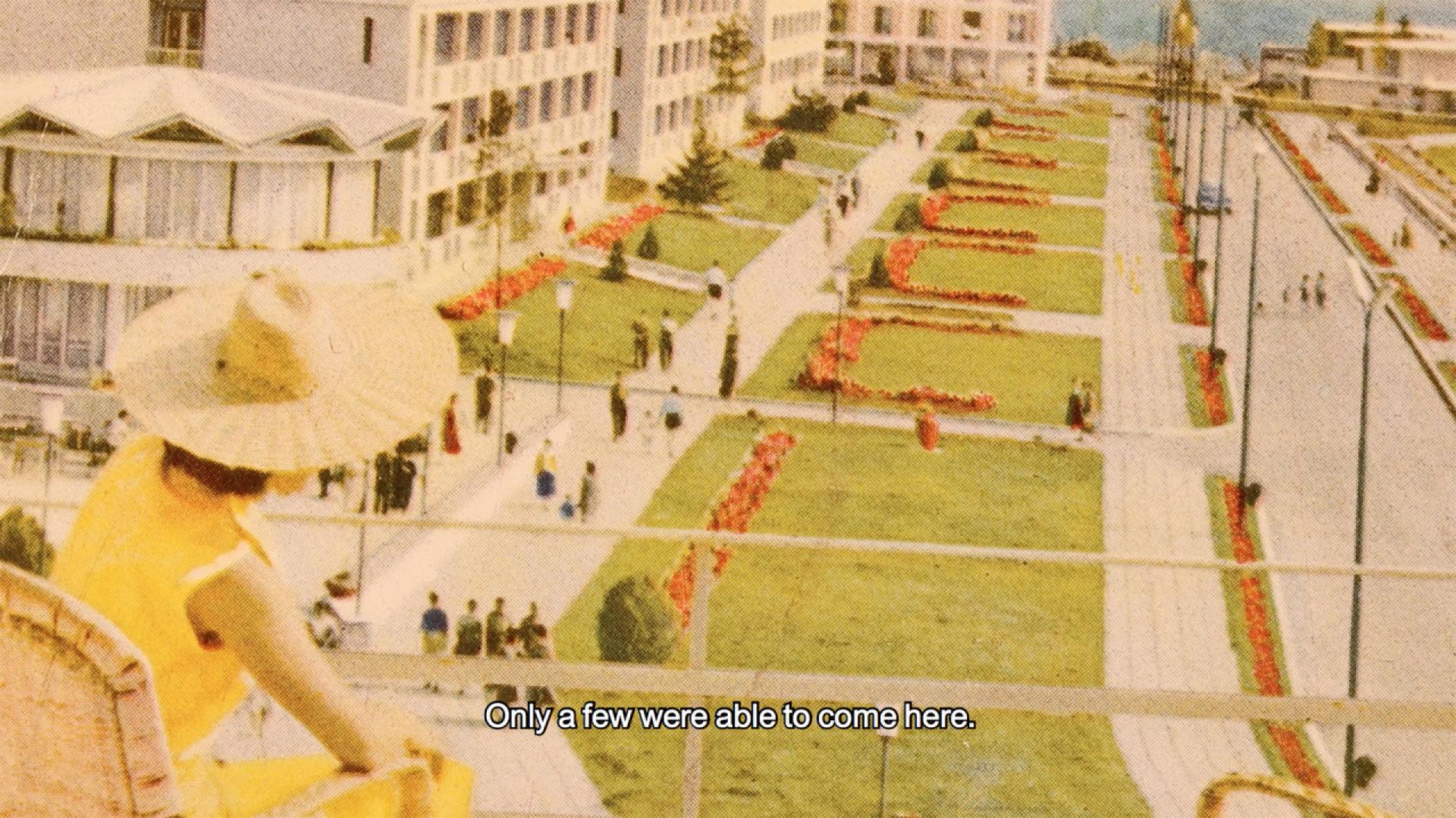

Two decades earlier, mid-1950s. After the communist regime in Romania was mainly preoccupied with annihilating all possible opposition in the first few years since its instauration, there came the time for it to fulfil its promises of triumphant modernity brought to the masses, not just to the privileged few, like in the earlier times. Thus began the seaside project, rather unassumingly at first, and eventually achieving an unprecedented scale. Although the architecture was key, two massive, tightly connected, and yet somewhat hidden mechanisms contributed to the popularity of what became a completely redeveloped coastal area fitted for the newest leisure concepts of the time.

By associating the postcard images with the layered story of the seaside resorts, certain filmic qualities become apparent.

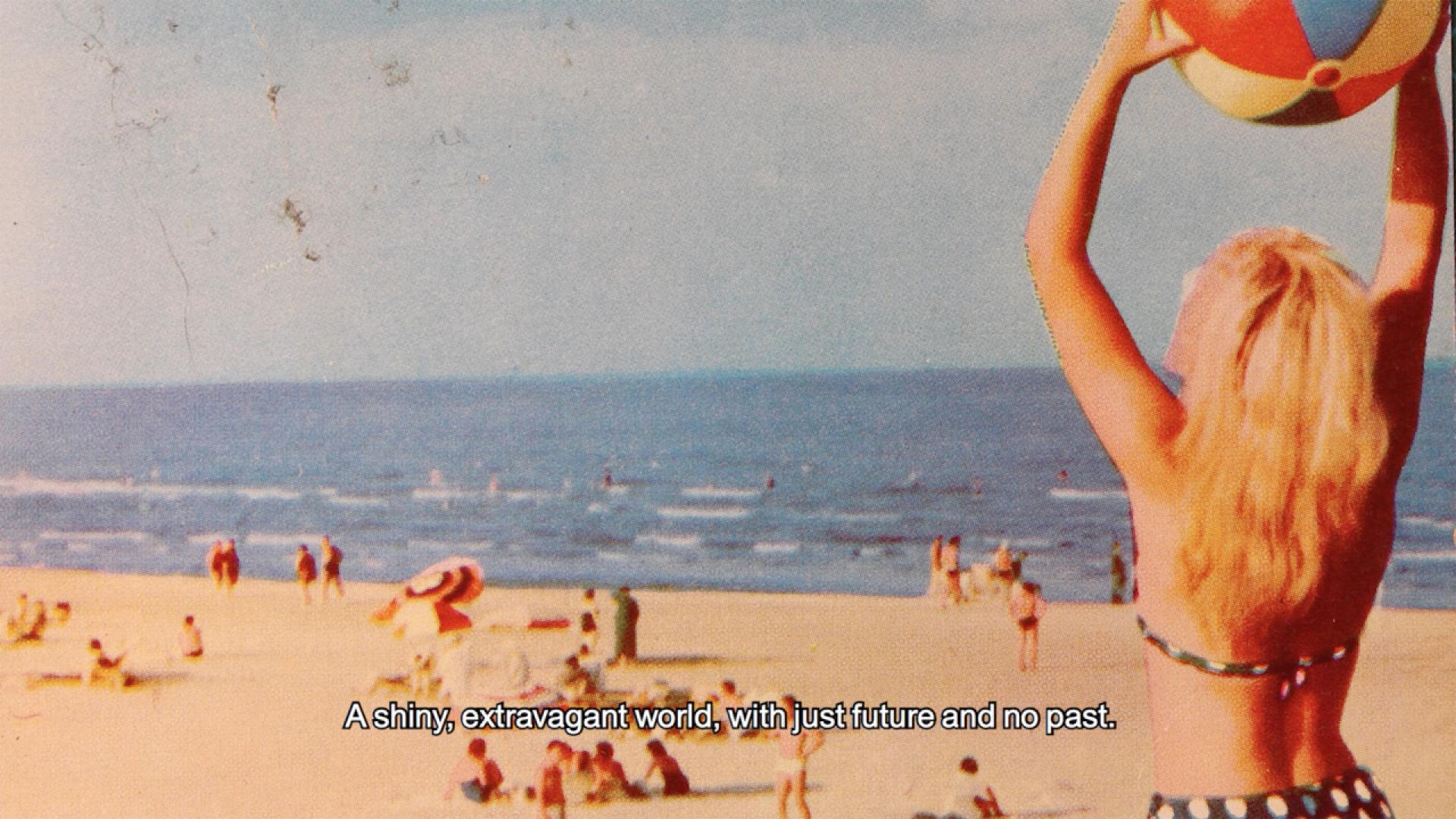

The seaside project was fuelled by the communist regime as a gesture of political power, to assert its ideological and technical advancement, to both its people and the foreign countries of the socialist East, as well as the democratic West. In this context, a second mechanism was much needed in order to frame and disseminate the achievement accordingly. As such, a vast propaganda, easily hid under the pretence of mere enthusiasm for the benefits of seaside leisure, became one of the most effective tools in the hands of the regime. Postcards might have been the most accessible and tangible souvenir after the passing of time, but the youth of the 1960’s experienced an entirely novel visual culture building this effective narrative of the seaside paradise through music, brochures, videos, festivals, fashion, films, radio broadcastings, advertisements and all things hip amongst the young generations of the time.

The visual style of the postcards detaches the content from its actual temporality through its utopian and universal aesthetic. As such, the images leave room for speculation.

What the entire visual culture established around the seaside holidays never made clear was the brutal reality of the stark discrimination and the deep level of control the regime had over its people. Behind the carefully composed images, a very different story was taking shape. Behind the modernist façades, tangible and intangible walls divided the holiday makers. Foreign tourists were evidently preferred over locals ones, benefitting from superior services, and although the regime was claiming equality for all, certain social groups such as peasantry and lower-working class were constantly denied access to the seaside facilities. As such, the postcards depict an idealised, if not fictionalised, narrative of the seaside holidays, placing architecture as a key character and not merely a set design element for the attractive beach scenes. Entire resorts become an urban-scale scenography hiding in its backstage the actual political agenda.

Fiction becomes a powerful tool for grasping the actual reality.

Although the communist regime was openly criticising the capitalist system, it acknowledged its benefits and was keen to attract foreign tourists that were prioritised over local ones. Thus the availability for the latter was reduced and they were most often treated with services of inferior quality.

With their visuality hanging between past and future, in an imaginary time that stimulates nostalgia as well as the imagination, the postcards leave room for speculation behaving as frames from a film where politics and architecture intertwine. The references to utopia are inescapable, however coupled with the individual stories, the images start to gain depth and the architecture begins to shelter an unsuspected multilateral reality. This is how “Coastland”, a short experimental docu-fiction, was born — it explores the potential of the seaside visual collection in order to redefine, deconstruct and reconstruct its architecturalnarrative in an imaginary future.

Through their careful composition and enhanced by the complex narrative behind them, the postcards readily become frames in a film reflecting the unseen forces behind a seemingly paradise made true.

Enlarging the pixels is like looking through the cracks of the perfect image in order to find the traces of the actual truth — behind the general beach euphoria, individual dramas depict a different reality.