What Fundamentals? Revisiting Treasures In Disguise: The Ominous Ruins Of Montenegrin Modernism

In today’s Montenegro, the remains of the 20th century architecture often stand as reminders of the opportunities squandered. Suffering the insufficient upkeep, poorly executed renovations, planned destruction, or death by neglect, modernist buildings are fading away – quietly retreating into the twisted skyline of a post-socialist city.

As the new urban reality emerges from the multiple crises of the last three decades, formed by piecemeal plans and projects (often permitted through murky decision-making procedures), sharp edges of the surviving modernist structures point towards a wistful “what if”. What if these buildings were used to envision and create cities that are more egalitarian, more sustainable, more just? Could the old idea of using architecture to make the city better reshape this used concrete into spaces for the community to learn and grow? Seems justified, reasonable, fundamental.

Treasures in Disguise at the 2014 Venice Architecture Biennale. | Photo © Patricia Parinejad

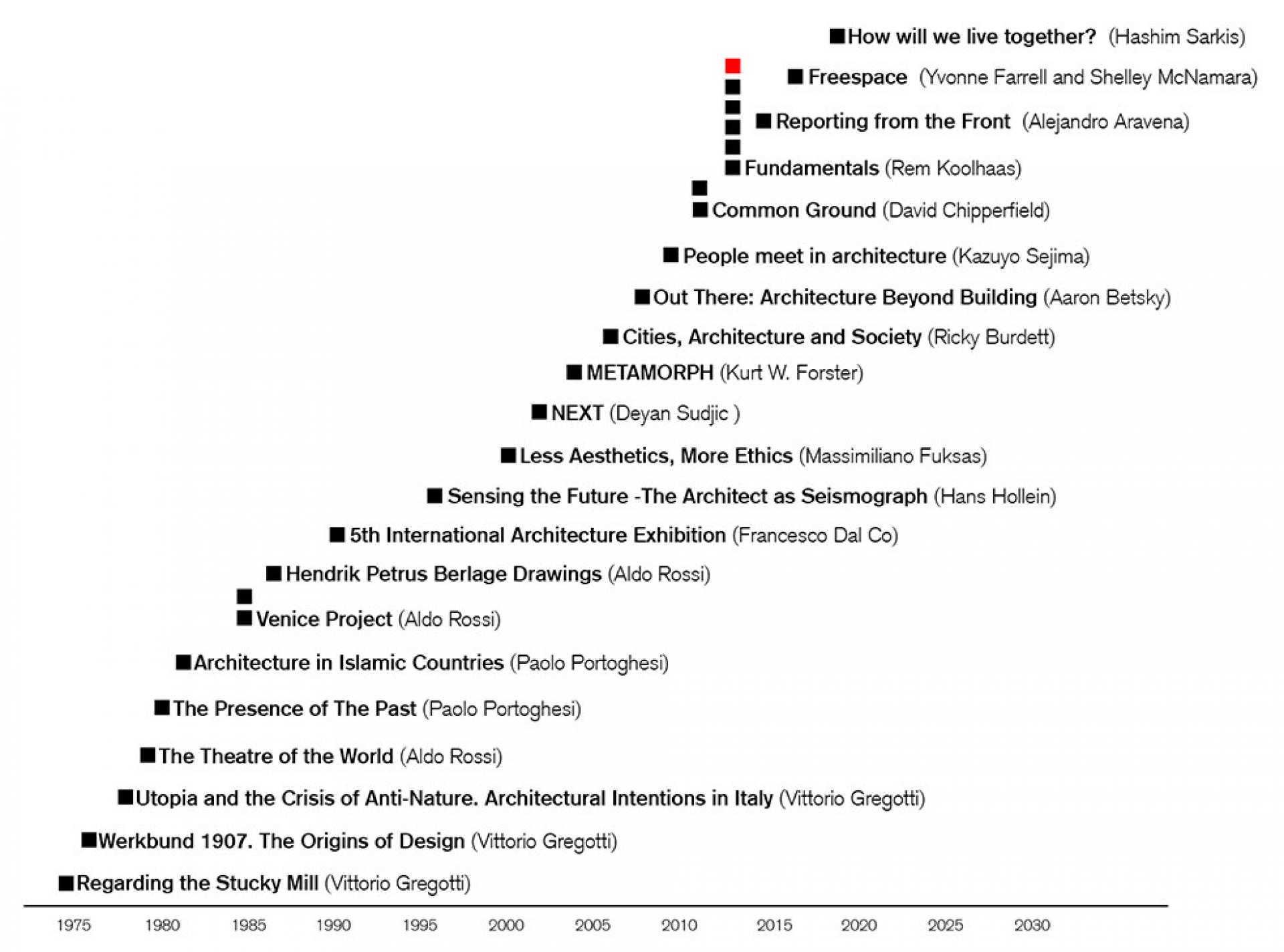

In 2014, Fundamentals was the title of Venice Biennale, curated by Rem Koolhaas. The national curators were asked to respond to the topic of Absorbing Modernity 1914-2014, and Montenegro presented four of its modernist structures in an exhibition titled Treasures in Disguise: treasures for the undeniable value of the works on display, disguise for the veil of indifference and neglect enfolding them. The international team of curators behind the exhibition set out to explore what is to become of these and other modernist buildings scattered around Montenegro and to present them as resources, as something to work with, to build upon, rather than erase. It was a well-received effort: numerous visitors praised this opportunity to discuss the richness of historic layers, the relationship between architecture, society, and politics, and the importance of sustainable building practices. The unusual exhibition design was also appreciated for featuring large-scale models mounted in a narrow space, highlighting the discrepancy between the grandiose modernist structures and a tight spot they have been pushed into nowadays. Montenegrin Minister of Sustainable Development and Tourism said how showing Treasures in Disguise in Venice “shows that Montenegro is ready to reevaluate its ignored architectural legacy and to rehabilitate buildings that are currently unused and decaying.” Then the exhibition ended.

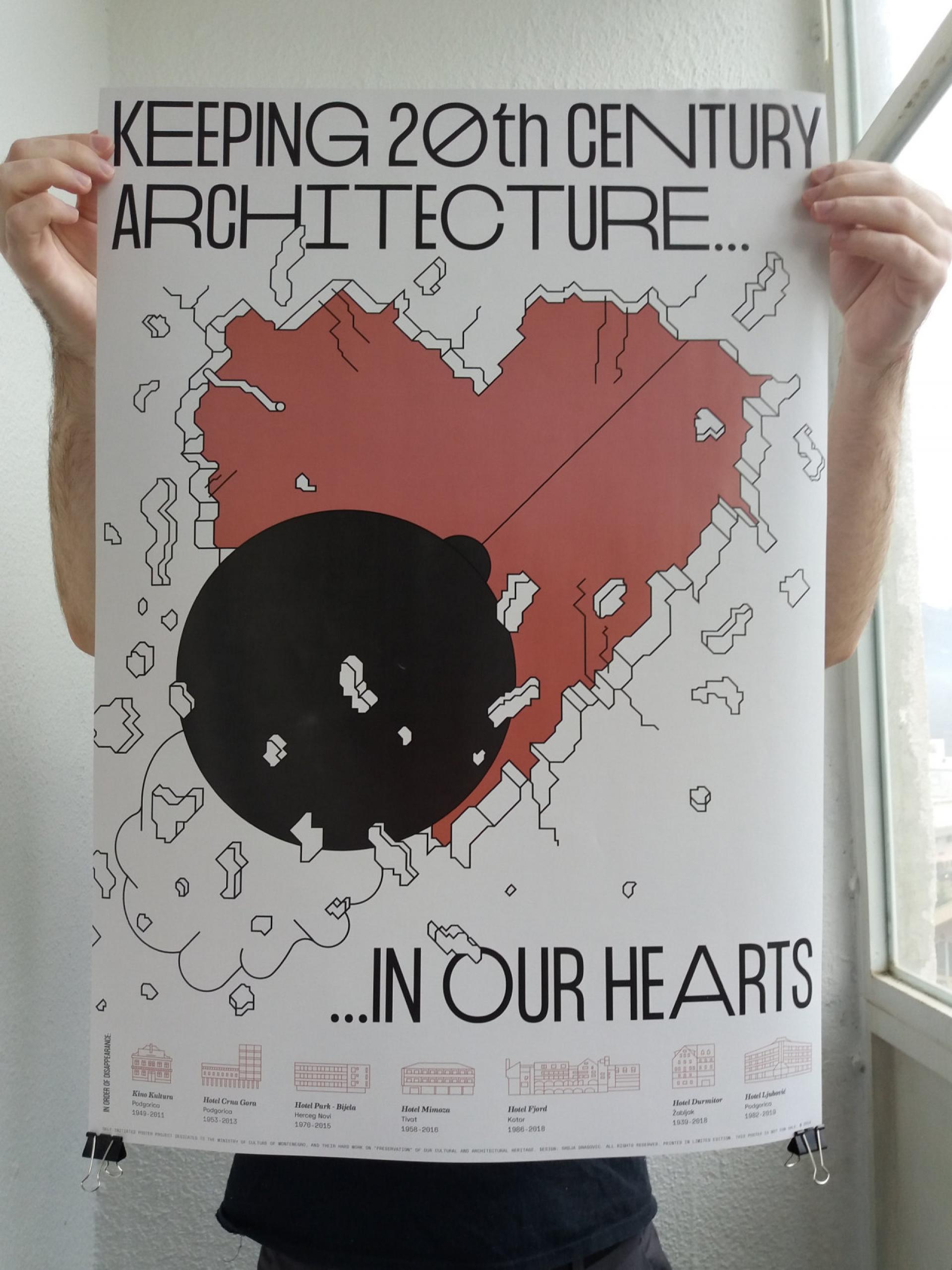

Poster commenting on the treatment of the XX century architecture in Montenegro. | Source © Srđa Dragović

The concepts, the messages, and the ideas presented at the 2014 Biennale seemed to carry the potential to change the hearts, the minds, and the politics of modernist heritage protection. However, in the years since 2014, half a dozen of modernist buildings in Montenegro have been torn down, with many more scheduled for demolition. How does this make sense? The political support for rediscovering the Treasures in Disguise, voiced before the world in Venice, turned out to be entirely divorced from any actual, systemic action on behalf of Montenegrin authorities. This discrepancy between what gets promoted as important and what gets treated as important reflects the paradox of the contemporary spatial development of Montenegro, crucified between the idea of the world’s first ecological state [1] and the reality of utter economic dependence on mass tourism and foreign investment. Development policies keep reaffirming rather than trying to change this reality, hence creating a downward spiral in which both natural and architectural heritage are sacrificed, spatial resources depleted.

The avatars of the destroyed works of modern architecture in Montenegro. | Illustration © Srđa Dragović

The case of Hotel Fjord, one of the four buildings presented at the 2014 Biennale, is illustrative. Built in 1986 after the design by Zlatko Ugljen, whose work was showcased recently at MoMA’s exhibition Towards a Concrete Utopia, Fjord occupied a prominent location across the water from the Old Town of Kotor, hanging in a provocative balance opposite its Medieval walls. The fact that the hotel was included in the Venice Biennale exhibition did not save it from being demolished in the spring of 2018. The owner, eager to start developing a new project in its place, rushed to remove the building even though the demolition works would overlap and interfere with the upcoming tourist season. Once the hotel was turned into a heap of rubble, local landfills were not able to manage the sudden influx of such an enormous amount of solid waste. The debris stayed for more than a year on the spot where the hotel used to be, weighting heavily on two consecutive tourist seasons, reminding both the locals and the visitors that buildings cannot just vanish into a thin air. It was a practical lesson in sustainability, an illustration of the difficulty brought about by the arrogance of taking down an existing structure with plenty to offer, just for the sake of putting up something new and elusive. Case in point: Fjord’s plot remains vacant, as all the building activity in Kotor came to a halt due to ongoing concerns over a potential loss of the UNESCO World Heritage Site status. Praising sustainable while practicing unhinged development can only go so far. While it is not possible to know what comes next for the Bay of Kotor, it is clear that Fjord was denied a chance of a second life.

The foundational stone of Dom Revolucije lies discarded and abandoned in a city center parking lot. In the upper-right corner, a promotional banner for a local gym is visible. | Photo © Stojan Stamenić

Another structure included in the 2014 Pavilion, Dom Revolucije, never actually got to have a proper life at all. This giant memorial center designed by Marko Mušič – another important Yugoslavian architect – has been standing at the center of Nikšić since 1989, when its construction was interrupted due to a lack of funding. In the years since the Biennale, the curatorial team behind the Venice exhibition managed to help organize and win an international competition for the reconstruction of Dom Revolucije. Through a series of careful adaptations, the project was supposed to finally bring the estranged colossus into the city life. However, this attempt came undone and was discontinued soon after it started, as it became obvious the local authorities preferred not to stick to the plan and started recklessly reshaping the structure, tearing parts of it apart. The entire effort put Dom Revolucije in the spotlight – and possibly marked it open for business. Today, different sections of the building are rented out to various establishments (a gym, a supermarket, a TV studio, etc.) for a period of 30 years, along with a privilege to, seemingly, rebuild and adapt the structure as they wish. No unifying vision, no engagement with the past, no synergy effect: just an eclectic bunch of private commercial spaces, sharing the origin story of a treasure undisguised.

The events following the hopeful Montenegrin presentation of the modernist heritage at the 2014 Biennale reveal the lack of systemic consideration for spatial development. The absence of strategy stands in a way of creating a more nuanced, more inclusive approach to imagining urban future – and gives the floor to the highest bidder, along with the permission to move fast and break things. Within such a system nothing is perceived as essential, as part of the whole, as important enough to consider, to protect, to learn from: nothing is fundamental. That is why it would be a mistake to consider modernist buildings of Montenegro – or even its modernist ruins – as failures. The buildings did not fail, the system around them did. It is just that a few of them are still standing, as reminders that they're (still!) is another way.

Notes:

1. According to the country’s Constitution, Montenegro is an ecological state. The Declaration of the Ecological state was first adopted in 1991.

Sonja Dragović is a researcher in the fields of urban studies and critical geography. She obtained a joint master’s degree in urban studies in 2015 within the interdisciplinary program 4Cities, which consisted of four semesters of study and practice in Brussels, Vienna, Copenhagen, and Madrid. Prior to this, she earned a bachelor’s degree in economics. Her main interests include analyzing practices of urban activism and working with local communities towards improving participatory methods, public policies, and shared spaces. She is a member of KANA/Who if not an Architect, a group of architects and urban researchers dedicated to the preservation of modernist architectural heritage and to the study of policy and practice of contemporary urban development in Montenegro.