The Invisible Church

It had been about 100 years since anyone last saw her. Rumors about an unlikely find of Marco Polo’s remains in her depths, and the supposed beauty of an unseen altar announced her delayed return. I don’t remember her façade —even when she stood at the front of San Lorenzo square, I couldn’t describe it— now completely covered with colorful banners, announcing the opera of the composer Luigi Nono. [1]

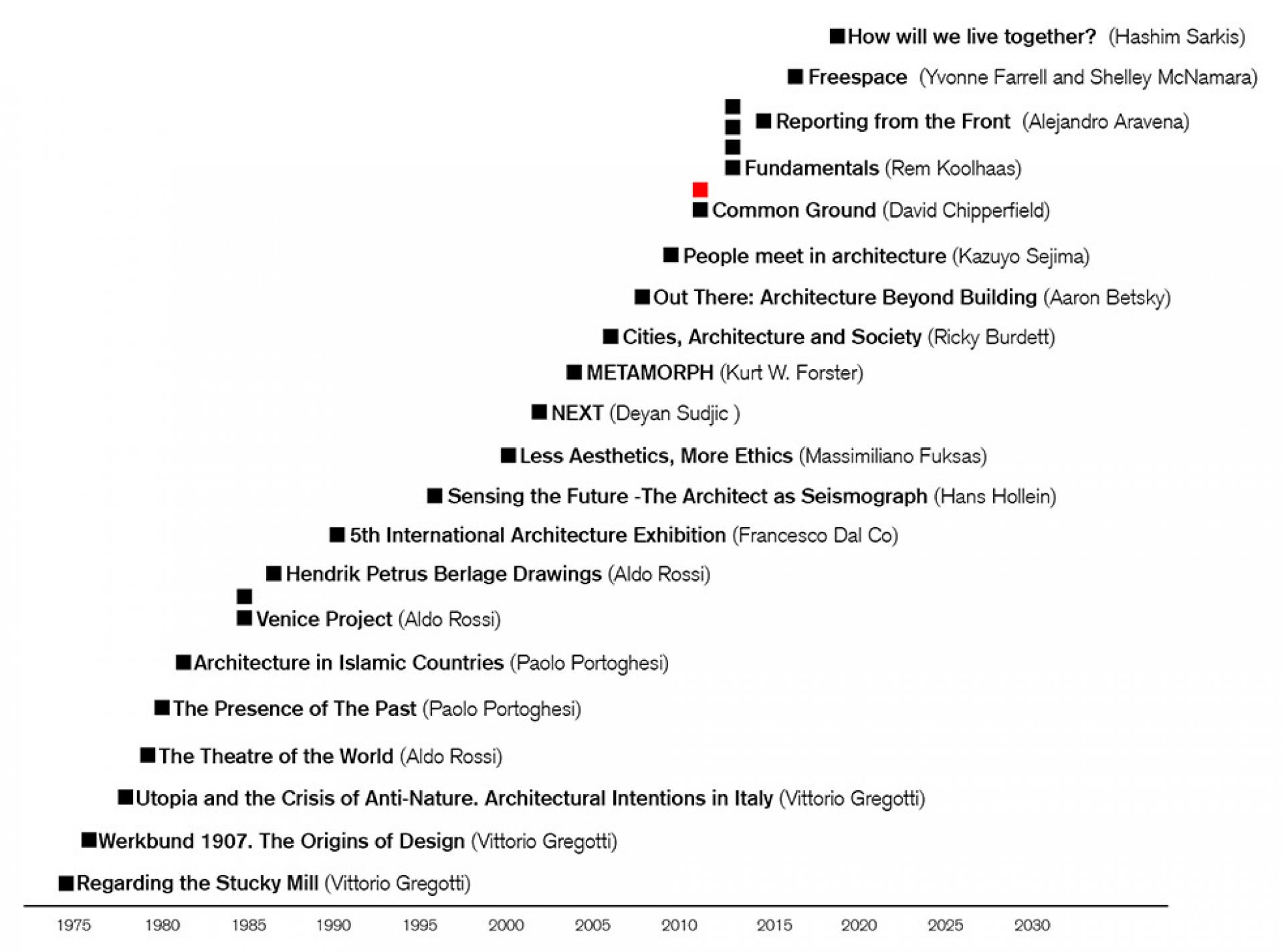

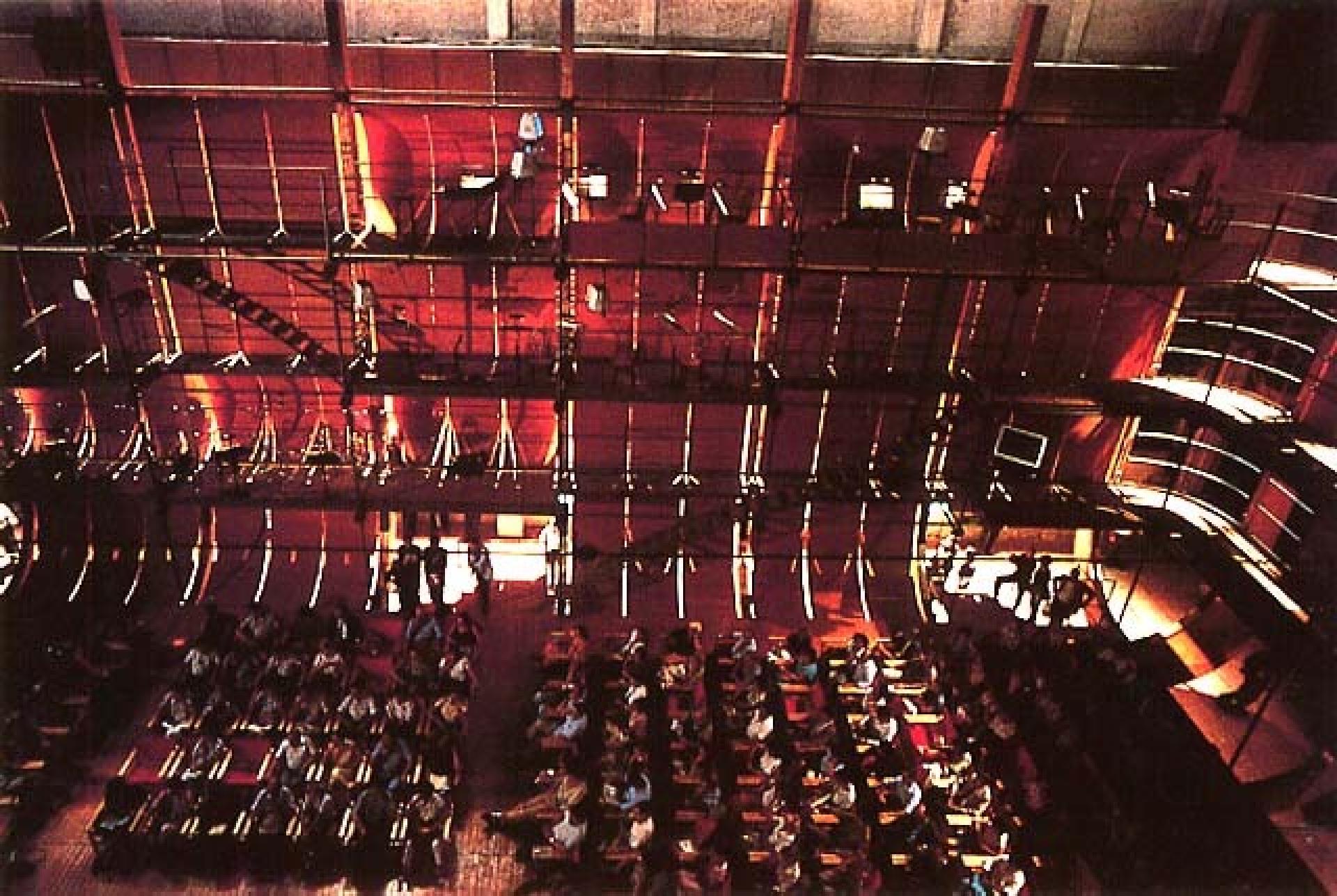

The structure designed by Renzo Piano on that evening occupied it all; a maze of scaffolding, where to navigate it was to play a role in it, and a brief description of the “huge musical instrument and sounding board that housed the stage, audience and orchestra” [2] to be seen from the seats at the center of that all-encompassing stage.

Music Space for Prometeo Opera by Renzo Piano Architects (1984), San Lorenzo Church, Venice, Italy | Fondazione Renzo Piano

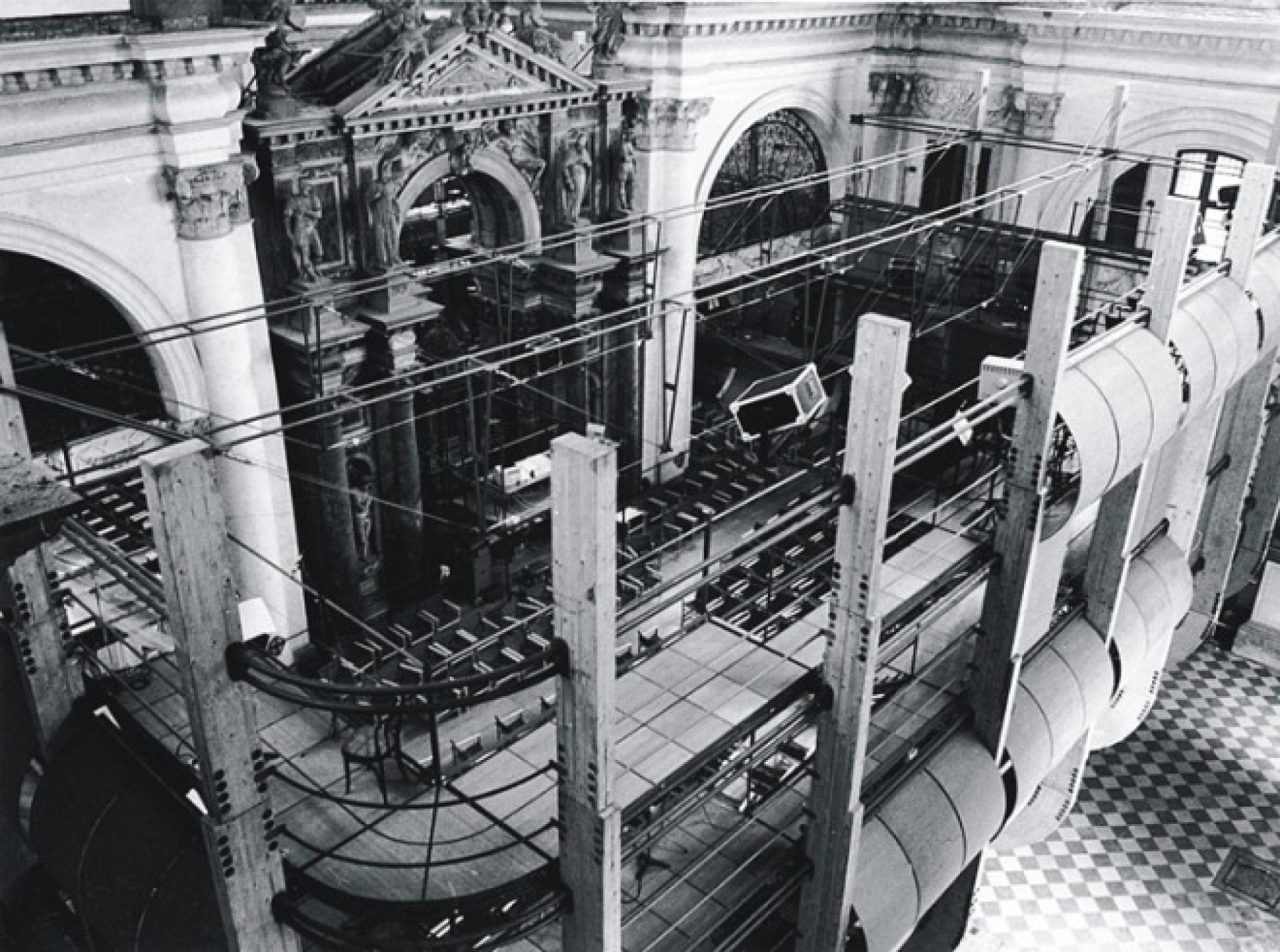

Music Space for Prometeo Opera Section Drawing by Renzo Piano Architects (1984), San Lorenzo Church, Venice, Italy | Fondazione Renzo Piano

Everything was ruddy, shadowy, and indistinct. Even more so when they had just lit up the stage and my eyes were dazzled, and I was barely able to see that enormous door wide open, through the vast and incredible hole that swallowed the whole of the lower portion of the altarpiece.

Music Space for Prometeo Opera by Renzo Piano Architects (1984), San Lorenzo Church, Venice, Italy | Fondazione Renzo Piano

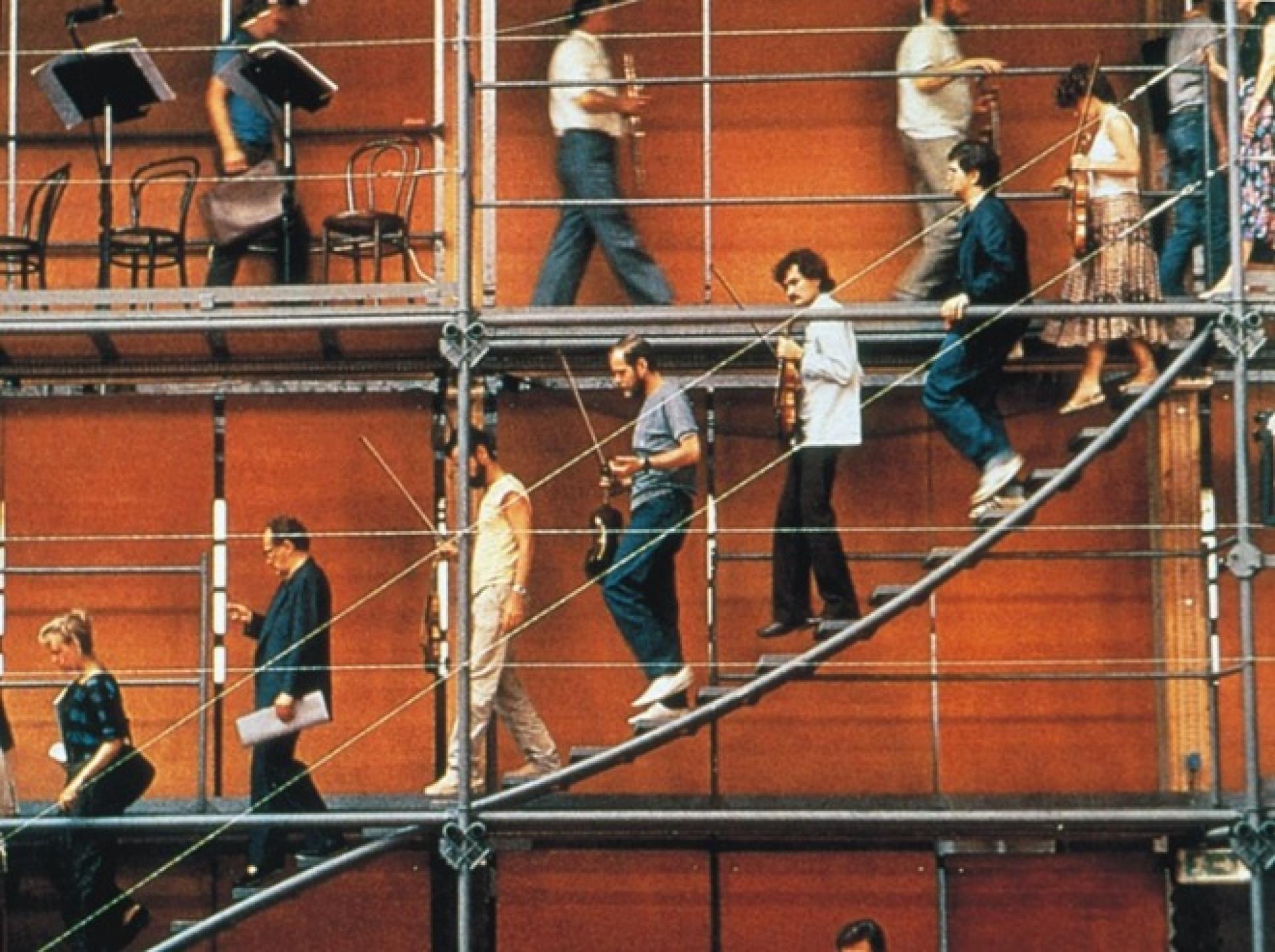

The musicians positioned themselves along the staircase, the lights dimmed and Prometheus began to fill the room with its flame, in a musical conversation between the wooden panels, the omnipresent scaffold and the hidden walls of the church.

Prometeo Opera Musicians Rehearsal (1984) in San Lorenzo Church, Venice, Italy | Fondazione Renzo Piano

I like to believe the music made her visible for a moment and I was able to see her face —even if covered— for the night.

Prometeo Opera Opening Night (1984), San Lorenzo Church, Venice, Italy | Fondazione Renzo Piano

Maybe it was just the illusion of wanting to see her real face. Maybe it was the face of Prometheus before the doors of light and thunder closed again. [3]

“Black here and white there-in patches. She’s a kind of half-breed, and the colors come off patchy in places instead of mixing. I’ve heard of such things before. And it’s the common way with these venues, as anyone can see.” [4] The reality is that the church was invisible. She had always been. [5] Piano and Nono’s imagination created a place that fitted in with what they thought they knew about her glaring real absence. They dressed her in masks, clothes and artifices for her to become them in time. In this little church, form was background. What we witnessed there was not a mere representation of Prometheus; it was Prometheus. Beyond the brief moments that her stolen radiance lasted, she would stay only Prometheus. [6] For the more they included her in the conversation, the more invisible she was to all the present. The church was silent and nodding, and those were her best qualities; a magnificent vision of what real invisibility means —the mystery, the power, the freedom, the licentiousness— where they saw no inconvenience in disposing of the helpless building. They arrived at the conclusion that a destitute church could become the manifestation of anything.

Twenty-eight years elapsed since the Italian music and pyrotechnics, when the Mexicans arrived with their ideas for promoting folklore. [7]

Culture Under Construction - The Collectivity of Cultural Space Installation Photo Montage 2012, San Lorenzo Church, Venice, Italy | Arquine

The same biennial, the same pretensions, the same assumptions, the same scaffold, that now covered her from the outside; new brighter and more colorful banners fluttered in the Venetian summer breeze laying over the church once more.

Culture Under Construction - The Collectivity of Cultural Space Mexican Pavilion at the Venice Architecture Biennale 2012, San Lorenzo Church, Venice | Arquine

Culture Under Construction - The Collectivity of Cultural Space Mexican Pavilion at the Venice Architecture Biennale 2012, San Lorenzo Church, Venice | Archdaily

Culture Under Construction - The Collectivity of Cultural Space Mexican Pavilion at the Venice Architecture Biennale 2012, San Lorenzo Church, Venice | Biennale di Venezia

The gesture stood as a true triumph of artifice over reality, choosing the most crowded moments of its square to show the cultural power of a distant country, which found itself eagerly seeking to show its appreciation for the ruin, preservation and millennial constructive capacities. They decided to elevate the scaffold and extended it to the façade —as the Italians had done in their time to her interior— covering the church’s entrance in its entirety with a pompous mask.

Culture Under Construction - The Collectivity of Cultural Space Mexican Pavilion at the Venice Architecture Biennale 2012 Front Facade 2012, San Lorenzo Church, Venice, Italy | Arquine

Culture Under Construction - The Collectivity of Cultural Space Mexican Pavilion at the Venice Architecture Biennale 2012 Front Facade 2012, San Lorenzo Church, Venice, Italy | Biennale di Venezia

With some ingenuity, imagination, but above all money, she assured them a visible place at the Biennale [8] at the cost of her own. But pacts are easy to break, especially if they are written on air and promised from afar [9]. They would soon realize the terrible contradiction: after the frantic gestures to recover the church by Mexico —which surprised more than one— the headlong pace after the summer that swept her away, the inhuman bludgeoning of all the tentative advances of curiosity, the taste for winter that led to the closing of doors, the pulling down of blinds, the extinction of candles and lamps after the party [10], the church was still empty.

San Lorenzo Church Interior 2012, San Lorenzo Church, Venice, Italy | Arquine

She disappeared for a while, but with the return of the Biennale-eaggered tourists that the summer brings, so did the scaffolding, this time to cover the wounds underneath Ariel Gusizk’s Cordiox [11].

Cordiox Mexican Pavilion at the Venice Art Biennale 2013 Installation 2013, San Lorenzo Church, Venice, Italy | Arquine

Still from Video Cordiox Mexican Pavilion at the Venice Art Biennale 2013 Installation in progress 2013, San Lorenzo Church, Venice, Italy | Marco Mosco

Cordiox Mexican Pavilion at the Venice Art Biennale 2013 Installation in progress 2013, San Lorenzo Church, Venice, Italy | Arquine

The inner emptiness was of absolute clarity; her invisibility transcended the concealment of her ordinary face. The Church for the first time was half-bare, and yet, the only thing we could —we wanted— see were her improvised clothes. Those scaffolds that had already become the building; whether to cover its altars, its ceilings, its facades, or its wounds, allowing us to see in time those transitory garments that, by opposition, had turned her into a mystery, a wrapped caricature, a silhouette. She would appear and disappear with the Biennale, but no one would notice or care anymore, so they cut her loose. When they removed the scaffold, banners and the lights, they only verified what we already knew. She had long been gone.

Cordiox Mexican Pavilion at the Venice Art Biennale 2013 Installation 2013, San Lorenzo Church, Venice, Italy | El Universal

Notes:

1. Prometeo (Prometheus) is an “opera” by Luigi Nono, written between 1981 and 1984 and revised in 1985. Nono scornfully labeled Prometeo a “tragedia dell'ascolto”, a tragedy of listening. The premiere of the first version was held at the Church of San Lorenzo in Venice on 25 September 1984. [Fondazione Archivio Luigi Nono ONLUS]

2. Designed exclusively for Luigi Nono’s opera Prometeo, this large acoustic space that can be fully dismantled, offered a chance to experiment with the profoundly intimate, even fruitful relationship that can exist between music and architecture. The traditional concept of the concert hall was revolutionized for the event, turning the space into a huge musical instrument, a resonant box housing the stage, the audience and the orchestra. The structure had to be erected first in the church of San Lorenzo, in Venice, as well as in the disused Ansaldo factory in Milan. [RPBW Architects - Renzo Piano Building Workshop, Prometeo Musical Space]

3. The design came to life in 1984 for the first performance at the deconsecrated church of San Lorenzo, in Venice as part of the XLI Biennale/ Musica, after which the structure was dismantled and reassembled a year later at the former Ansaldo factory in Milan. [RPBW Architects - Renzo Piano Building Workshop, Prometeo Musical Space]

4. Wells, H. G. 1998. The Invisible Man. Wickford, R.I.: North Books.

5. Over the centuries, San Lorenzo was known as a centre for music more so than a church, where celebrated seventeenth-century composer Antonio Vivaldi, performed and rehearsed. The church suffered damages during the Napoleonic War and, in 1810, was deconsecrated and all decorations except the main altar were removed. It closed to the public in 1865 and, in the early twentieth century, underwent a series of archaeological excavations, in search of the remains of Marco Polo. [San Lorenzo, Ocean Space]

6. The installation created by Renzo Piano for Luigi Nono’s opera Prometheus in 1984 created “an invisible theatre where the production of sound and its projection into space are fundamental to generating dramaturgy”. For Nono, music and sound predominated over images and the written word, as much as the building that served only as background for its stage to open up new dimensions of meaning and possibilities for listening. [La Máquina Sonora, Arquine]

7. The 15th of September 1984 was the last time that San Lorenzo was opened with the final concert performance by Luigi Nono with the architectural, acoustic and scenographic proposal of Renzo Piano. After 28 years of being closed, the old church reopens on August 27th with the inauguration of the Mexican Pavilion for the International Architecture Exhibition of the Venice Biennale, which was on display until November 25th. Mexico reached an agreement for nine years with the Municipality of Venice in order to restore the heritage site and use it as a Mexican venue for the biennials of art, architecture, film, dance, music and theater for the next nine years. [Las Capas De San Lorenzo, Arquine]

8. The Mexican State signed, in July 2012, the contract with the Municipality of Venice to have in comodato the former Church of San Lorenzo for nine years, not only committed to restore the property, but to have a constant cultural programming, allowing the entrance to local public one day a month and acquire an insurance against damages to third parties. [México Se Compromete A Darle Vida A La Ex Iglesia De San Lorenzo]

9. El INBA Excluye A San Lorenzo En Bienal De Arquitectura De Venecia

10. Wells, H. G. 1998. The Invisible Man. Wickford, R.I.: North Books

11. After having recovered with the 13th International Architecture Exhibition of the Venice Biennale (Culture under Construction), the Mexican Pavilion for the 55th International Art Exhibition of the Venice Biennale was opened in the old Church of San Lorenzo (The Layers of San Lorenzo). For this edition, the Mexican artist Ariel Guzik (Mexico City, 1960) was invited, who proposed Cordiox, a complex machine that describes sonorously the environment where it is located, spreading a crystalline, subtle and expansive tonal cadence, which favors an exceptional listening experience. [La Máquina Sonora | Arquine]

Tania Tovar Torres is an architect, writer and curator. She is co-founder and director of Proyector, a curatorial platform based in Mexico City devoted to the promotion of architecture research projects. Her practice focuses on alternative methods of architectural production and consulting for research and curatorial projects. She is currently professor at Universidad Iberoamericana and appointed curator of the Architecture Pavilion of the 2019 and 2020 Mexican Design Open. Previously, she worked at the Canadian Centre for Architecture in Montreal and at the Arthur Ross Architecture Gallery in New York. Tania holds a Master’s degree in Critical, Curatorial and Conceptual Practices in Architecture from Columbia University and a Bachelor of Architecture from the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México UNAM.