FOMA 37: Forgotten Greece

Forgotten Greece Masterpieces are obscure and understated, but still special in their own subtle way: it is the lack of fanfare, a certain restraint in the architecture that accentuates their genuine character, therefore they merit a closer look.

Concrete arches of Magoula Cemetery emanate an aura of Aalto’s wave designs or elements of Niemeyer’s Brasilia | Photo by Exporabilia

Each space comes with an interesting backstory and an evidence of how post-war ambition and civic pride fuses with classical tradition, science, folklore, religion and the natural environment. There is also an evidence of architectural brilliance mired in political persecution, indifference, schadenfreude or a lack of recognition by the establishment. Such storylines are as quintessentially Greek as drama and each might weave their unique pattern into the architecture.

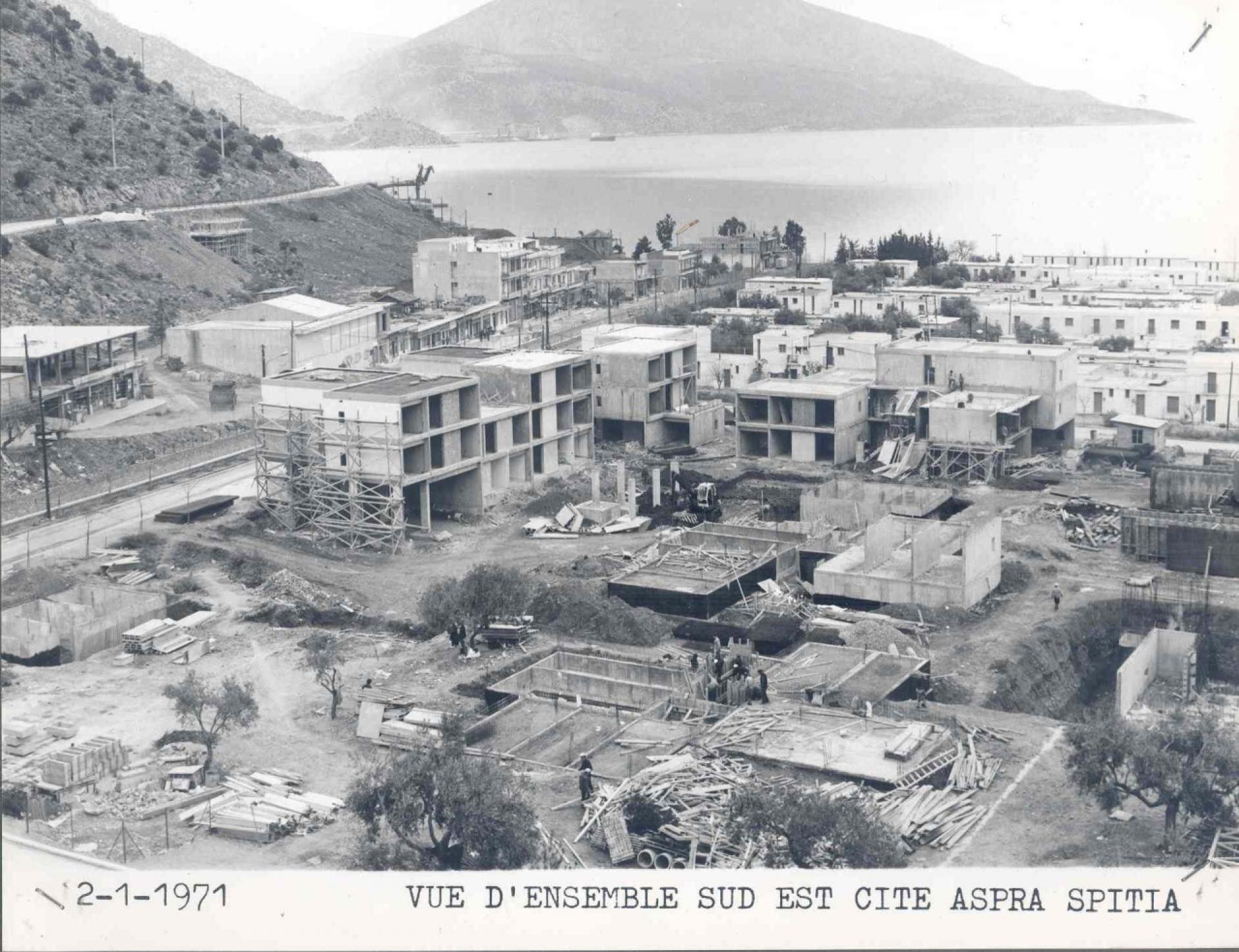

Aspra Spitia is a settlement to house employees of the Aluminum of Greece factory and mining operations west of Athens. | Photo via Fotiadis

Greeks demonstrated an innate affinity for siting and orientation since their temple building days of antiquity. Stillwell (1954) describes a mastery of form, angle, height and orientation: their temples were a planned succession of experiences that culminated into a grand, final approach of the cult image. Temple construction was an early use of architecture and urban planning principles to deliver a coherent visual and emotional result - exempli gratiaa transcendental, religious experience.

In post-war Greece, architect and urban planner Constantinos Doxiadis drew inspiration from the same fountain of knowledge. He created a seminal worker’s settlement that both transcended the provincial vernacular andchimed in fascinating consonance with its natural surroundings. It is like a place of eternal youth by design like Logan’s Run Caroussel, where residents never get to grow too old.

The construction phase on of Aspra Spitia. | Photo via © Doxiadis

Through Ekistics, Doxiadis approached settlements as complex biological organisms. | Photo via Voiotias

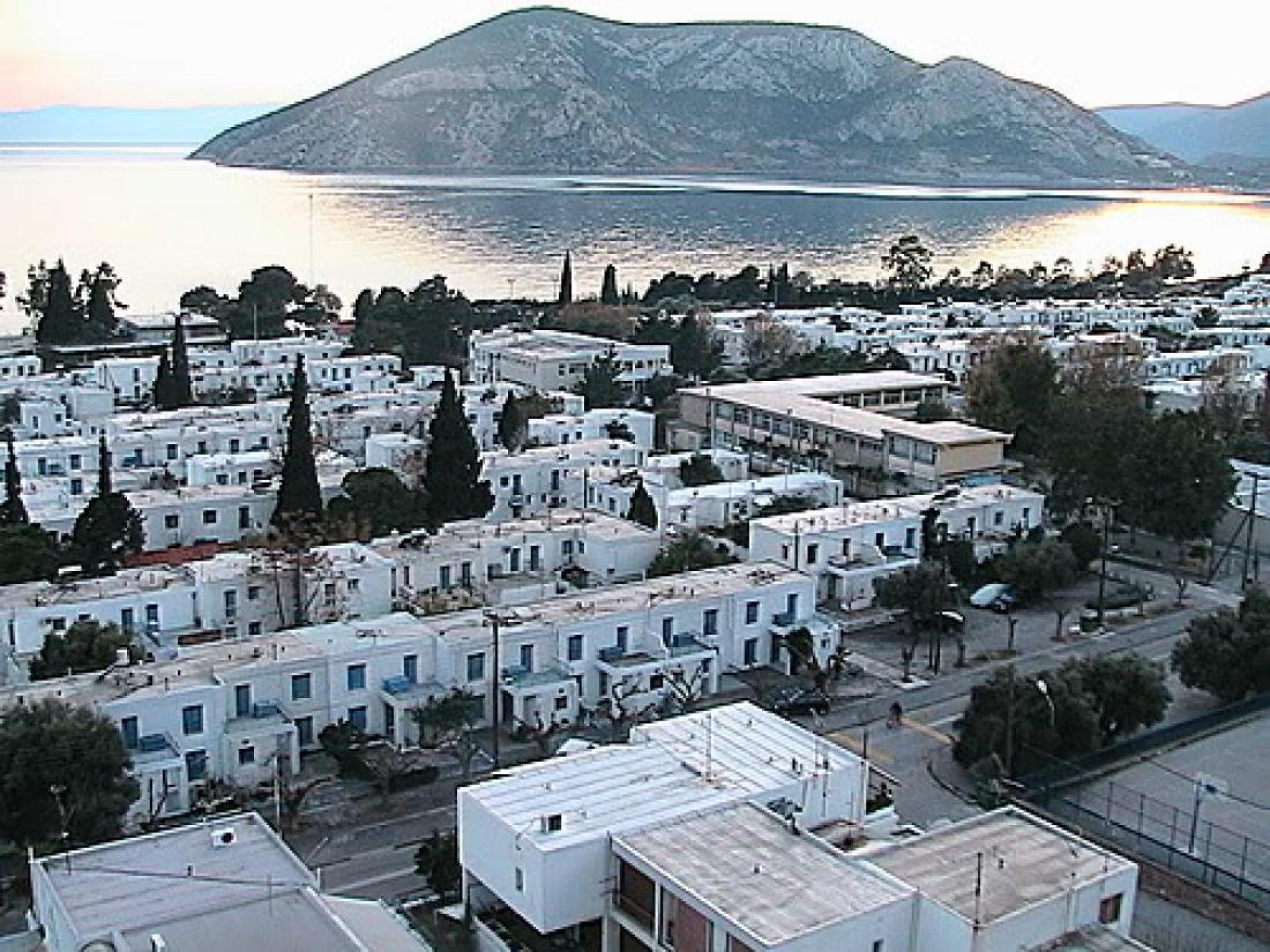

Aluminum of Greece was launched in 1960 as a joint venture between the government of Greece and an industrial conglomerate led by the historic French firm Pechiney, a world leader in aluminum manufacturing. As a result, the first aluminum production facility in the country opened on the northern coast of the Corinthian Gulf in 1966. Capitalising on the nearby bauxite ore mines (one of the largest deposits in Europe), the vertically integrated manufacturing process ranged from raw material extraction to the delivery of a range of secondary bauxite and aluminium by-products. It was an ambitious and successful industrial project that created new opportunities for employment for those prepared to settle there. The sheer scale of the industrial unit and its ancillary facilities, however, created an urgent need for housing the employees, prompting the creation of a new settlement nearby. They called it Aspra Spitia (White Houses), and to this day, it remains a model for small scale urban planning with a unique blend of Modernist yet distinctively traditional Greek aura.

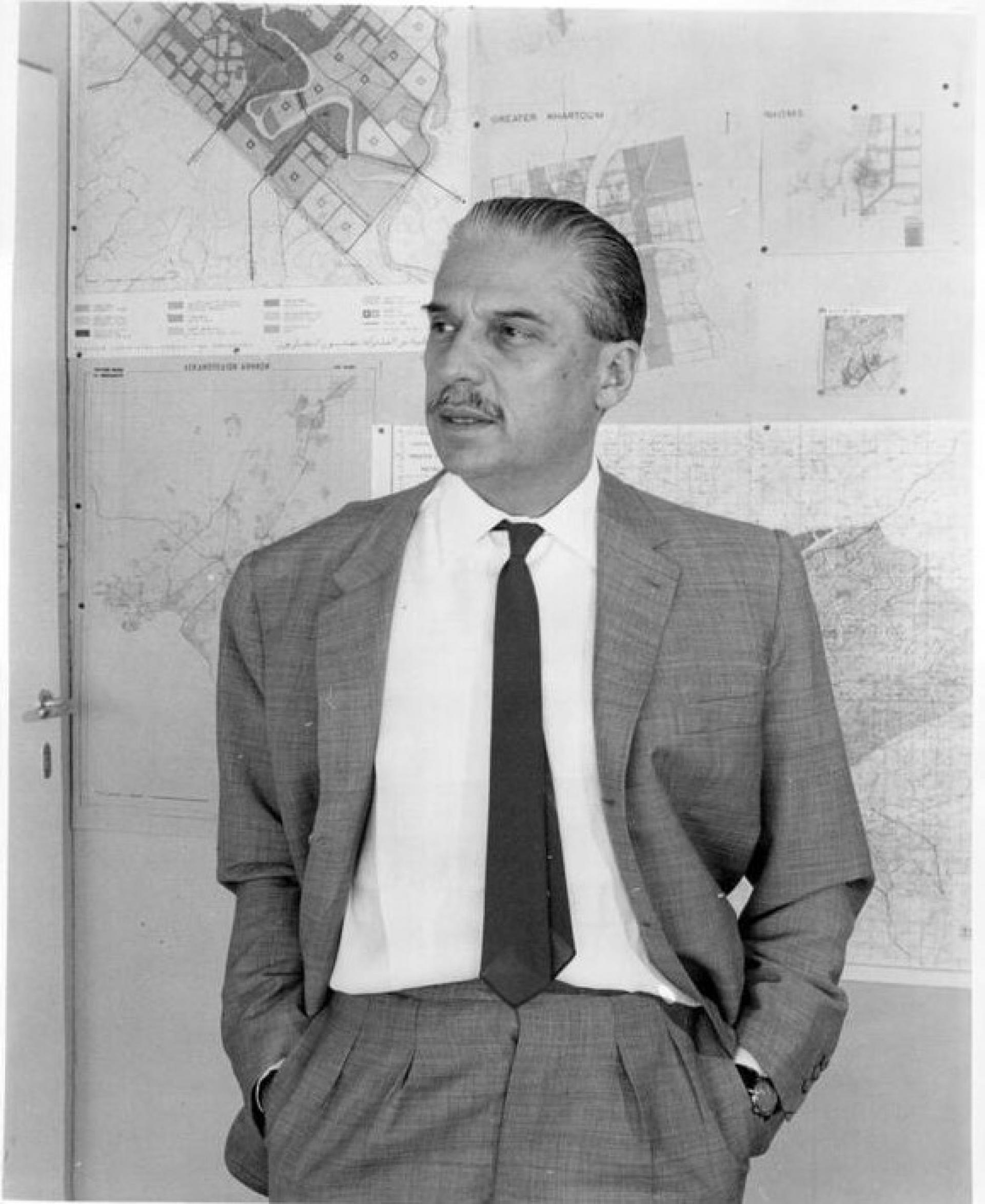

Constantinos Doxiadis in 1975

The urban planning, layout and design of the settlement was masterminded by Constantinos Doxiadis and his associates, who also delivered the first phase of the project. Doxiadis, an experienced urban planner who held various Public Works related government posts for the Greek government between 1937 and 1951, was a leading figure in the country’s post-war reconstruction effort. His private practice has been rising in international prominence since it was founded in the early 1950s; by 1959, he was appointed as chief urban planner for the city of Islamabad, Pakistan, while his firm was involved in numerous local and international projects, prompting him to construct a new headquarters in Athens to house their now 400 strong team of urban planners, architects, and engineers.

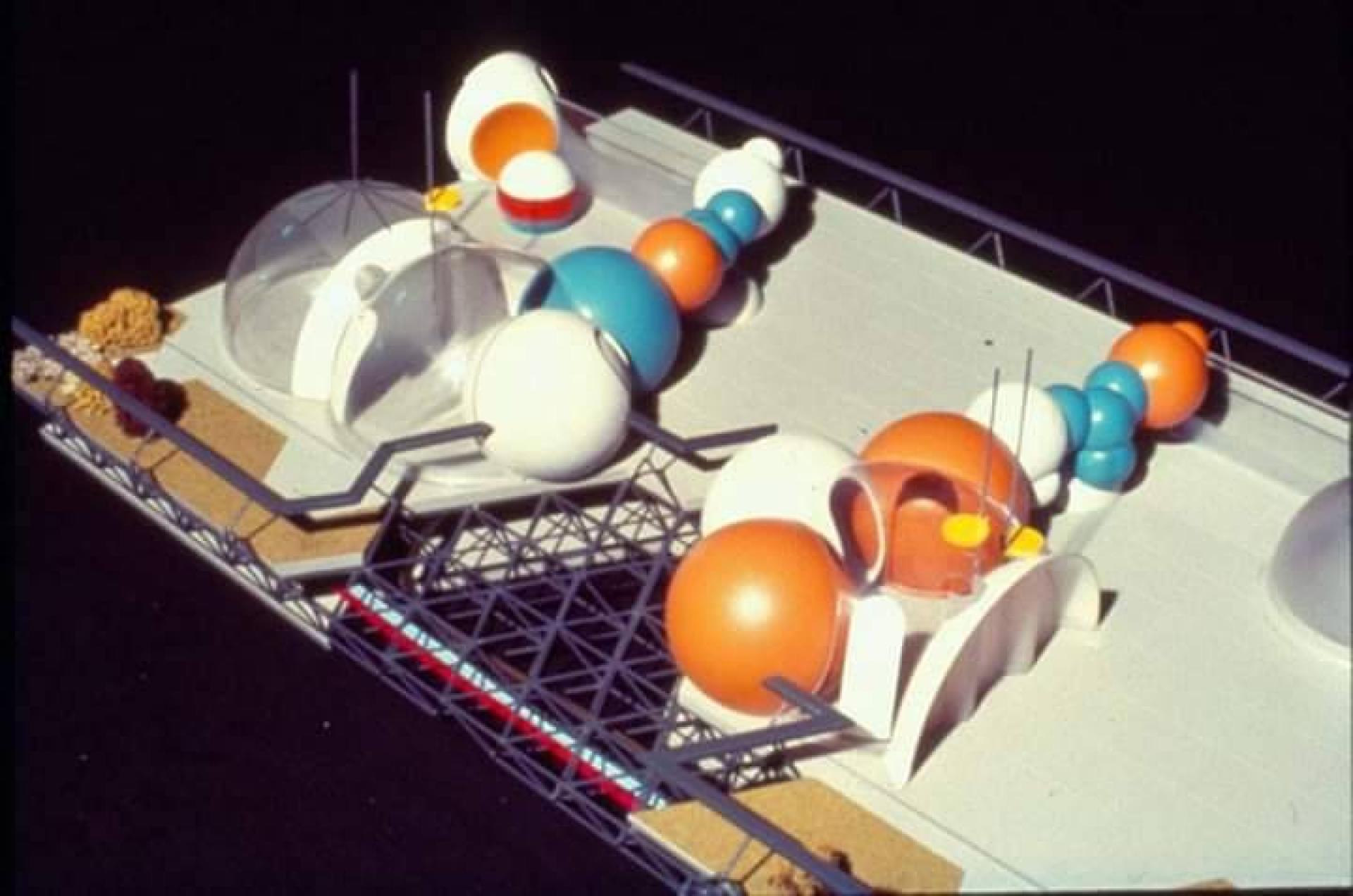

The model for Aspra Spitia. | Photo via © Doxiadis.org

Still, Aspra Spitia was a challenging brief: there was nothing but olive trees and a few vernacular shacks inside the tiny seaside valley. The first wave of French engineers settling at the newfound community were disheartened: this rugged slice of paradise had yet little to show in the way of creature comforts. And there was a looming danger in choosing to deliver a typical, prefab industrial settlement, with identikit housing units built around amenities: that choice of plan was expected to mark the marvellous landscape irreparably, presenting an unsuitable urban continuation of the industrial landscape at the nearby factories and mines. The new resident workers might feel disconnected, transient, and without a sense of belonging to the very habitat they might end up spending their entire career.

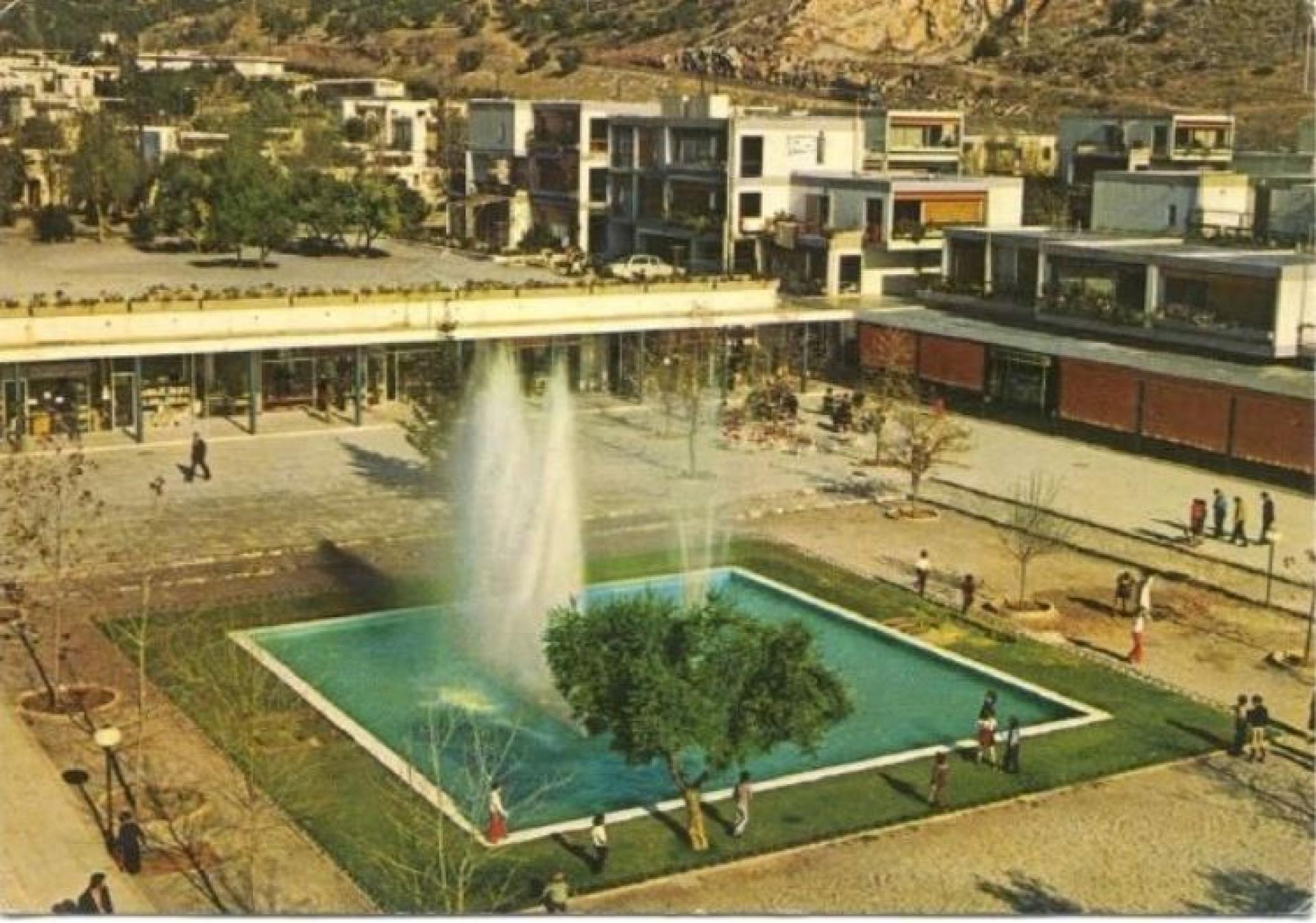

A commercial centre Tower | Photo via © astronayths.blogspot.com

However, Doxiadis had a clear vision about Aspra Spitia. His plan was informed by his Ekistics philosophy, first proposed in 1942 and constantly developed since. Through Ekistics, Doxiadis approached human settlements as complex biological organisms - capable of forming connections with each other, constantly evolving, merging and scaling in orderly harmony with the natural environment. And preserving the purity and beauty of the hills, the seafront, and the olive tree fields within the planning scope of a factory, mines and a worker’s settlement at Aspra Spitia became a key challenge. These very different, both natural and man-made constituent units demanded to be re-shaped into a natural fit. This wouldn’t be about forcing an irreverent, modern smudge in the landscape: it’d be about the foundation of an orderly, organic urban environment.

A corner unit of the Phase 1. | Photo via © astronayths.blogspot.com

Stairs from the Phase 2. | Photo via © astronayths.blogspot.com

Units from the Phase 2. | Photo via © astronayths.blogspot.com

Thankfully, Doxiadis’ Ekistics already proposed such a scalable hierarchy for ordering urban settlements – an arrangement that social and biological sciences concluded was important for the avoidance of chaos. And at the beginning of the scale, there was Anthropos – the individual. It was expected that the aluminium workers would be mostly recruited from the nearby rural areas. Therefore, understanding the familiar traditions those new settlers were expected to carry with them was a crucial design element, as well as preserving the individuality of each constituent unit: each house, each cluster, each neighbourhood had to feel fresh and special, but still flow with identifiable tradition and heritage, also retaining a degree of deference to the natural environment. And the whole ensemble needed to remain functional for its intended purpose, without reverting to picturesque anachronisms.

All these elements were carefully infused into the inverse L-shaped city plan, which follows the organic contour of the landscape closely: The long leg is flanked by hills, while the short leg is laid across the seafront. Within the resulting space, four neighbourhoods were created, each circled by a peripheral road. The civic, business and administrative forum of the city is located at the junction of the legs, while a recreation and tourism area is laid along the seafront.

The settlement’s main square.

The design of the residences and public spaces is where it all comes together. Twelve unique house designs were utilized, each standardized with interchangeable elements that enabled the architects to alter the design in intermediate stages of construction. This technique increased the resulting variety of house types to twenty-five, while further variations were achieved by mixing-up the properties of each street in terms of house orientation, elevation, set back, and corner placement. Therefore, each home and each neighborhood look unique, but also retains a thematic familiarity with the whole ensemble of the town.

Both natural and modern materials are utilized, concrete, wood and local stone. The walls and stone are mostly whitewashed, offering a traditional Greek visual clarity to the settlement. Some stone walls remained natural with intent, in cases where these blended visually with the surrounding olive groves. The preservation and integration of existing olive trees in squares, yards and street layouts was prioritised, and supplemented by re-planting as well as new plantings. Stone fences, pergolas, steps and pavements complete the textured landscaping of each neighborhood, while well placed cul-de-sacs, squares and public thoroughfares complete the harmonious balance of private and public spaces.

Stairs from the Phase 3. | Photo via © Photiadis.gr

Aspra Spitia was completed in three phases, and now boasts 1072 residences housing approximately 3.000 residents. After the completion of the first houses and amenities by Doxiadis Associates, the city expanded both vertically and aesthetically with additions by C.Lembessis, P.Massouridis and M. Photiadis. A series of high rise, larger apartment blocks as well as specific amenities for the individual needs of the workers and the families were erected. These include a business centre, a nursery, and even a Catholic church for servicing the religious needs of the French settlers. One of the most ground breaking amenities was the installation of a sewage water treatment plant, which was the first of its kind in Greece at the time.

A series of specific amenities for the individual needs of the workers and the families were erected, like the nursery. | Photo via © Photiadis.gr

In terms of administration, Aspra Spitia is not far from the purpose-built, model socialist towns of the former Eastern Block. The settlement belongs to Aluminium of Greece (AL), and working in the mines or factories is a prerequisite for obtaining a house or a flat. A point system exists to help fulfil housing needs accurately, allocating the right type of property per household size. Residents are only required to pay a token monthly rent, while all property maintenance and upkeep is handled by the company. Naturally, these privileges last only for the duration of employment. Workers who wish to move on to another company or reach retirement age aren’t eligible to stay anymore: they are required to vacate their house, after making all necessary alternative arrangements. This is a town where people are not expected to grow old, and the reason why a cemetery was never planned as part of the urban grid (the nearest ones can be found in surrounding villages).

If Ekistics is about approaching urban environments in biological terms, then Aspra Spitia possibly holds the secret for urban immortality: free from the mortal vestiges of permanence and ownership, this is a model town that is, and will remain as fresh and tidy as planned over half a century ago.

The Church. | Photo via © astronayths.blogspot.com

The next stop is a few miles across the water from Aspra Spitia, where a forgotten Isthmia Prime Motel presents an abstract expression of three Classical disciplines: architecture, mathematics and music.

The unassuming roadside motel by the Isthmus of Corinth is an intriguing cross between Brutalism and the Classical Orders. | Photo by © Exporabilia

In its heyday, the main motorway linking the greater metropolitan area of Athens to the city of Corinth in the south west was one of the busiest arteries in Greece’s road network. Built between 1960 and 1969, the motorway would hug the craggy cliffs outside the capital with its narrow ledge, offering breath-taking, and somewhat dangerous views of the sea below. Vehicles would naturally slow down at the Isthmus of Corinth, the canal that allowed shipping to navigate the strip of land connecting the Peloponnese to Attica. The slow crossing of the Isthmus Bridge enabled passengers to admire the view of the man-made chasm below, and traditionally led to a quick pit stop on the other side of the canal.

The Isthmus region was becoming a very popular weekend escape with Athenians post war. At about one hour drive from the capital, it was near, yet far enough to enjoy the sea and fresh air. Small villas and seaside hotels sprang out in local villages and hamlets for weekenders to escape the hustle and bustle of a rapidly urbanizing Athens.

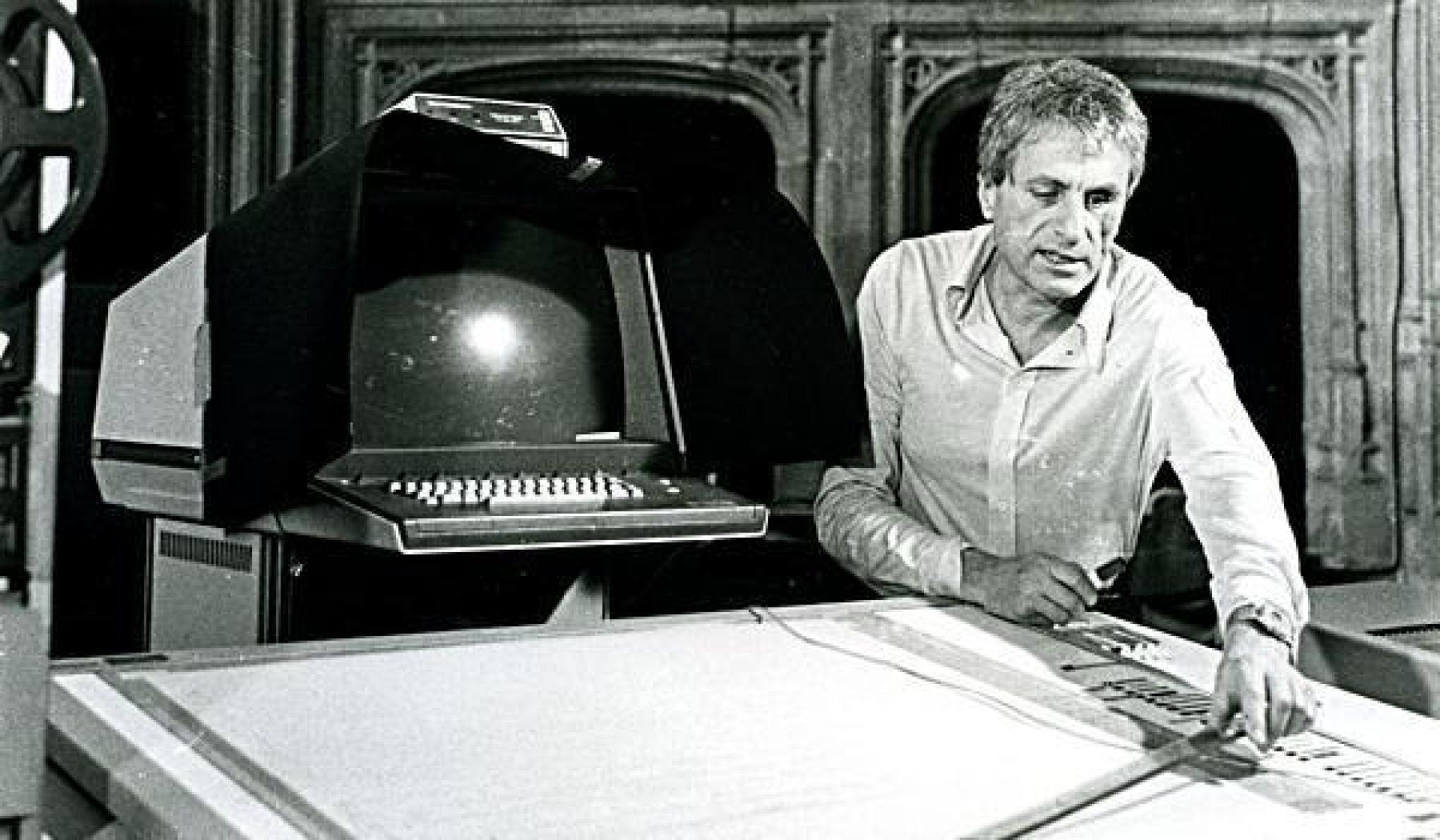

Panos Spiliotakos presenting his work. | Photo via © ema-arch.com

It is at this popular stopover area past the canal, where the strangely alluring hotel was built in 1969 in a collaboration between composer Iannis Xenakis and urban planner Panos Spiliotakos, two visionary friends expressing their common architectural heritage.

Iannis Xenakis | Photo via © Adelmann Collection of Françoise Xenakis

Xenakis was perhaps the most well-known of the duo. He was a Greek multidisciplinary artist with a passion for music and engineering and an unquestionable aptitude in both. He survived the war suffering a terrible face wound - caused by shrapnel from a shell fired by a British tank into a crowd of Communist protesters demonstrating in the streets of Athens in December 1944. As a qualified engineer, he left for Paris in 1947 where he worked under Le Corbusier at the Unite D'Habitation and Convent De La Tourette.

Le Corbusier with Iannis Xenakis. | Photo © Iannis Xenakis

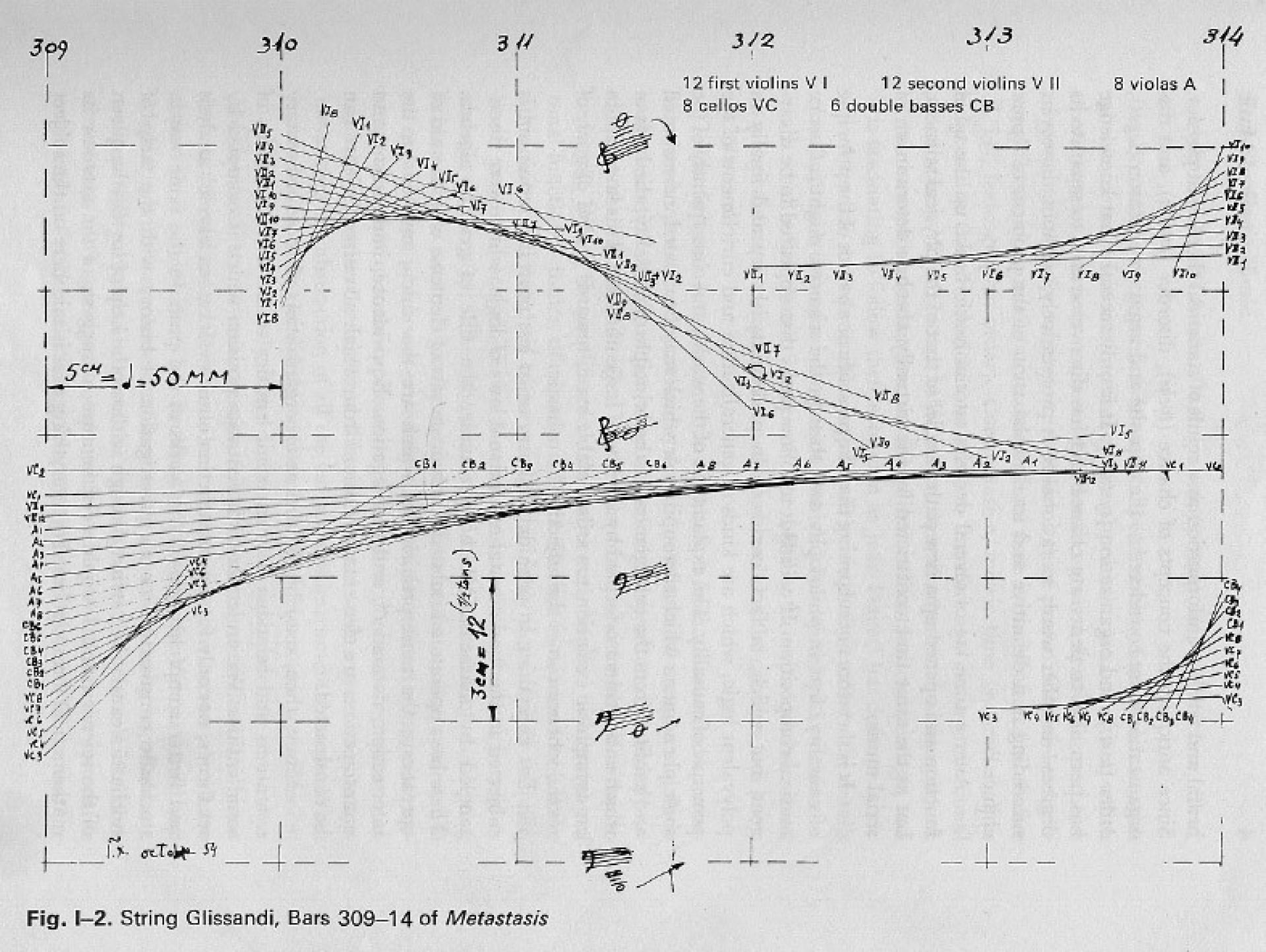

During that period, and through his own musical culture, Xenakis soon realised that the same complex spatial geometrical patterns applied in Le Corbusier’s architecture - the structural calculations, the intersecting tones and curves - could be applied to the composition of music too. His seminal 1955 musical work Metastaseis (lit.transmutations) was inspired by Einsteinian ideas about time and space, and utilised the mathematical principles of the Fibonacci sequence and the Golden Section structured around Le Corbusier’s architectural calculations. It shocked the world of contemporary music at the time: this was original Brutalist music, with all the sonic cantilevers, rebar and board marking you could handle.

The Algorithmic Compositions of Metastaseis

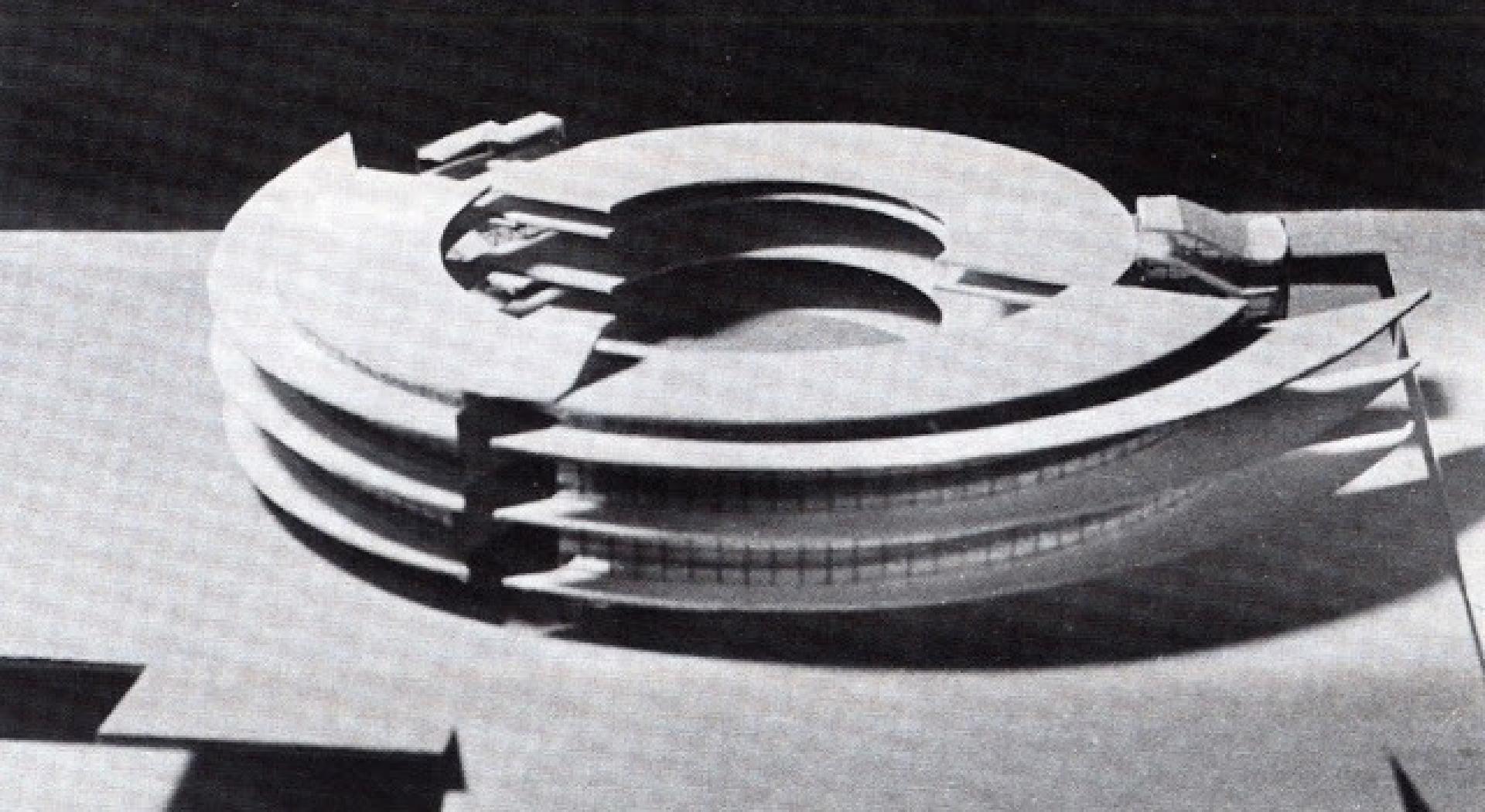

Xenakis’ knowledge of architecture allowed him to use graphic notation to represent his music. The string glissandi and other musical motions of his piece, representing sonic beams with time on one axis and pitch on another, looked less like sheet music, and more like a blueprint. With Le Corbusier occupied in the construction of Chandigarh in India, Xenakis went on to design the Phillips Pavilion in Brussels Expo 58 on his behalf. It’s a unique marriage of music and architecture, with its hyperbolic paraboloid masses deriving from the musical landscape of his own Metastaseis.

Inside the Pavilion, an expansive array of speakers and dials were arranged in an acousmonium: an avant-garde playback device used to spatialize musical scores. The array had been invented in the 1940s by proponents of musique concrète, an experimental circle of composers with whom Xenakis was associated. Further musical scores by Xenakis and Edgard Varese were performed this way throughout the pavilion, creating a unique meta-experience that fused architecture and music like never before.

The Phillips Pavilion in Brussels Expo 1958. | Photo © Wouter Hagens

True to the genius of Iannis Xenakis, the building by the Corinthian Isthmus emanates a classical aura throughout. Built as a modern diversorium (a roadside inn), it reflects the long Graeco-Roman resort heritage of the area. The sulphur baths at nearby Thermae (today’s Loutraki) attracted visitors since the antiquity. Many classical villas and baths have been discovered in the region through the years. It makes perfect sense that Isthmia Prime’s characteristic main entrance colonnade is made of 12 stern, board-marked concrete columns, a Modernist throwback to the Doric order of the nearby Temple of Apollo. The colonnade is supporting the 3-storey main residential block, with the rooms arranged obliquely to the main axis to maximise the beautiful views of the Gulf of Corinth beyond.

The colonnade is supporting the 3-storey main residential block, with the rooms arranged obliquely to the main axis. | Photo by Exporabilia

The triangular concrete antefixeson the flat roof is another wink to the floral anthemiaof antiquity, the decorative palmettes that adorned the eaves of ancient Greek and Roman buildings. The block is intersected by the reception and services area at ground level, allowing for a practical green area at the front with a star shaped pond. Iannis Xenakis reminded us that rhythm, as symmetrical repetition, is the ancient, supernatural bond that links mathematics, music and architecture. Isthmia Prime is an elegant, if somewhat forgotten example of these classical and artistic traditions, fused expertly together with his characteristic elan.

The building at Corinth is a Modernist throwback to certain familiar artistic traditions of Classical antiquity. At the corollary of this Athenian-centric luminary ethos, there’s a counterpart a Spartan-centric ethos, founded on the principle of selfless sacrifice as the pinnacle of civic achievement. Naturally, there’s less opportunity to go down fighting under a hail of arrows in our day. But dedicating one’s life in the service of the state is here presented as a visual metaphor of Sparta’s finest traditions in the Modernist Necropolis of Magoula.

The waveform of the Magoula Cemetery is symbolic of the up’s and downs we go through life. | Photo by Exporabilia

The new city of Sparta was founded in 1834 at the behest of Otto, the Bavarian prince who became the first King of Greece in the aftermath of the nation’s successful war of independence. He embarked on a revivalist program that aimed to modernize and urbanize Greek towns. The project was led by Eduard Schaubert,a Prussian architect and topographer who studied under Karl Friedrich Schinkel in Berlin’s Bauakademie. Schaubert also re-designed Athens, Pireaus and other major Greek cities, finely tuning their plethora of Classical and Byzantine sites with the Neoclassical neighborhoods, squares, and administrative buildings that typified the Greek national revival. This is how Sparta, previously obliterated by the Goths in the 4thcentury, was restored by royal decree in 1837. The re-established Sparta became, in fact, the first of the new Greek towns whose design was based on an actual urban plan – thus breaking with the disorderly, vernacular yoke of medieval urban spaces.

A century later, Sparta remained a quaint agricultural town, virtually unchanged since Schaubert planned it. The beautiful neoclassical facades were crumbling, and the street grid had deteriorated and was unsuitable for the ever-increasing motor vehicle traffic. The sewage system was old, and problematic. What’s more, modern Sparta was a city with a distinctive lack of modern facilities and monuments – it was becoming lethargic, almost as if the Goths had somehow travelled forward in time, sacking it again into oblivion.

There are entrances to either end of the arches, one leading to a small functions area, and another to the ossuary. | Photo by Exporabilia

The man who changed all that was Georgios Sainopoulos, the philanthropist who became mayor of Sparta for two terms, over a period of 8 years between 1964 and 1978 (interrupted by the Colonels’ Junta, who ousted him between 1967 and 1974). Sainopoulos dedicated his life to the improvement of urban life in Sparta, delivering numerous projects related to sport and cultural facilities, new road & water network infrastructure, and monumental public art. The 1964 cemetery at the satellite hamlet of Magoula was created at his behest - this was his birthplace, and where he seemed to make an almost personal statement about his intention to take the city out of its enduring quagmire, and into an era of progress. The cemetery, alongside other luminary philanthropic projects, was realised via donations he secured from close relatives Ioannis and Catherine Sainopoulos, Greek emigres based in Oklahoma, USA. He then invited local architects Charilaos and Sophia Polychronopoulos to deliver his vision of a surprising modern necropolis that exceeded conventional expectations.

Windows reflect the bright Peloponnesian sunshine in the colors of the CIAM grid green, red, yellow and blue, creating a kaleidoscope of colours inside the space where the funerary chests are kept. | Photo by Exporabilia

Sainopoulos might have been informed by his own experience of monumental modernism as a visitor during the Olympic games of Helsinki in 1952. It would have been an inspirational showcase of Nordic Modernism, exemplifying Olympic ideals, and much of it can still be admired to this day. The waveform these arches form at Magoula is said to be symbolic of the ups and downs we experience throughout life. There are entrances to either end of the arches: one leading to a small functions area, and another to the ossuary, both decorated with saints and religious figures made out of bent rebar. The windows reflect the bright Peloponnesian sunshine in the colours of the CIAM grid: green, red, yellow and blue, creating a kaleidoscope of colors inside the space where the funerary chests are kept.

Ancient Spartan traditions exemplified order and simplicity in all aspects of life, which often carried into funerary rites. Spartans were buried among the living, in anonymous graves inside the city walls. Only those fallen in battle, or women dying in childbirth were deemed important enough to merit their names on gravestones, typically lined up along busy thoroughfares & promenades – therefore transforming their tombs into public monuments. Further inside the Magoula cemetery proper, it is evident that several graves have been created in deviation to the unremarkable, marble-clad basilica orthodoxy of Greek cemeteries: the scale, shapes and materials are different, and there are statues, busts, carvings and funerary symbols that simultaneously reflect a sense of civic grandeur, and a closer affinity to the Western European funerary canon.

Shapes and materials of graves are different, statues and symbols reflect a closer affinity to European funerary traditions. | Photo by Exporabilia

Leonidas, the famous king who fell in Thermopylae was perhaps the most well-known son of Sparta. It is said that his remains were posthumously transferred to Sparta and deposited at Leonideon, a rectangular tomb close to the agora that can still be seen today. And as opposed to the more modern, extra muros Roman burial traditions, there’s consequence in the way that the tombs of all true citizens become very much a part of the living urban space. But especially the tombs of those who, like Leonidas, contributed significantly more to perpetuate the lore of their communities, become monuments of civic pride, and public remembrance. Uniquely, Sainopoulos’ own resting place is a sizeable vault, accessible through a flight of steps near the entrance to the cemetery. It is a feature rarely - if ever - seen in contemporary Greek cemeteries, and underlines the important character of the site’s mastermind. Arguably, this space represents a somewhat obscure link between the principled simplicity of the Spartans and the visual clarity of Modernist architecture. Deciphered in the key of the region’s Spartan heritage, the beautiful ensemble at the cemetery of Magoula is so much more than the average burial site usually seen in Greek towns : it is a poignant memorial showcase of lives well lived in the service of the local community, beautifully conveyed through the avant-garde architectural mind set of the 1960s.

An eclectic, monumental ensemble that fuses Classical, Byzantine and Romantic architectural styles. | Photo © M. Hulot

The civic principles of the Hellenistic world eventually clashed with the tenets of Christianity. In Greece this tectonic collision created new philosophical and artistic planes that inadvertently radiated their common roots, despite the necessities of doctrinal contrasts. Understanding this blend is quintessential to understanding the modern Greek psyche. The temple of Agia Foteini of Mantineia is the ideal visual representation for this melding process.

In the sunlit Arcadian plain close to the ancient city of Mantineia, there’s a church like no other. It’s an astonishing melange of styles, combining elements of Classical, Byzantine and Modern architecture, and yet remaining true to none. Its construction is the life’s work of architect and iconographer Kostas who has delivered an epic display of drama, faith and devotion that has astonished and divided ever since.

Heroic Tomb, Jacob’s Well and the Church’s Entrance. | Photo © M. Hulot

Papatheodorou was exposed to gothic religious architecture, particularly influenced by Erwin Von Steinbach’s work in Strassbourg Cathedral. After his studies he returned to Greece in 1967, where he worked for the Ministry of Culture, studying further under the architect Dimitris Pikionis. During his tenure there, he was exposed to the idea of building a monumental church on behalf of the Mantineian Association, a cultural group dedicated to the preservation of the antiquities of Ancient Mantineia in the southern region of Peloponnese. Bewildered by the beautiful scenery, the majesty of the ancient site, and the character of local customs, he proposed the design of an extraordinary building that captured the region’s quintessence: a visual link among the Classical, Byzantine and Modern traditions of Arcadia.

A mosaic inside the church. | Photo © M. Hulot

He resigned his public service role in 1970 to dedicate himself to the project, which eventually became a lifelong commitment. No formal contract was drawn, funding was scarce, mostly based on charity grants and donations from locals and members of the Mantineian Association. Driven by an almost divine inspiration, Papatheodorou moved on location, living in a tent pitched next to the site. This way, he could absorb the spirit of the locality, and focus on the formative stages of the project unhindered. He was often seen roaming construction sites and recycling centres in nearby towns, gathering reject materials: cornerstones from demolished townhouses, leftover marble slab fragments, or broken clay tiles from old roofs. He worked mostly alone, collecting, measuring, chiselling the materials, shaping and piecing the fragments together into an astonishing monument that soon began taking shape. His only help was unskilled manual labour provided by local farmhands. The Classical and Byzantine parts and techniques merge into one another on the walls and bell towers of the church, creating a visual disruption that expresses the forward motion of history - as one era blends into another, leaving its indelible mark at the seams of history. The church becomes a visual representation of the area’s disparate yet interlinked memories, converging through the aeons to create a homogeneous body of local culture.

The main entrance. | Photo © M. Hulot

The main structure was completed by 1974, then the interior work began. Inside the church, we see the expression of the architect as an iconographer: The concept of stylistic variety continues, with sequences of religious and pagan themes combining on the mosaics and wall paintings. Classical symbolism such as meanders, pastoral or hunting scenes abound, and figures in ancient togas blend with Christian saints dressed in modern attire, such as jeans and t-shirts. It was too much for a portion of local clergy, who began raising eyebrows: certain offending visuals are then amended to avert the church being characterised as inappropriate for consecration. Conservative circles begin to gossip Papatheodorou, accusing him of irreverence and idolatry. Some others allege that he has unlawfully appropriated materials from the ruined temples and shrines of Ancient Mantineia to incorporate in his church.

But those who recognized and appreciated his work also lend their support – architects, archaeologists and art curators underlines the multidisciplinary reach of his work. The famous Greek painter Yiannis Tsarouchis described the church vividly as fresh water for those in thirst: “When I saw the church, I felt the elation one feels when a justified complaint is suppressed. I’ve heard people characterise Kostas Papatheodorou as an “aping architect”. What I found at the church, however, was a genuine heartbreak, a desperate confession. In our age of fake moralism and ludicrous rationalism, these rare qualities become as important as a vein of fresh water during drought”

The next few years saw the construction of two ancillary buildings, a miniature Classical shrine dedicated to local war heroes, and a fountain with a circular colonnade, representing the biblical fable of Jacob’s Well. The Church is considered work in progress to this day. Some contemporary critics stated that the Church of Agia Foteini of Mantineia is the Greek Sagrada Familia. This may be a somewhat flattering, even inflammatory characterisation for some. There are parallels, however, between the work of Antonio Gaudi and Kostas Papatheodorou as both churches are considered incomplete, both architects deployed their proficiency in a number of related disciplines, incorporating these in their design - ceramics and wrought ironwork for Gaudi, it’s iconography and mosaics for Papatheodorou. Gaudi pioneered the use of trencadís, his famous mosaics made of reject materials, broken tiles, shards of glass, china or shells. Papatheodorou employed a similar technique by fashioning reject materials - such as stones and tiles - as found into walls, towers and mosaics. Last, both architects are inspired by Gothic religious architecture, and they are driven and inspired by their faith, which leads them to wholly devote their lives in their work. Agia Foteini of Mantineia might not have the scale or monumental appeal of the Sagrada Familia. It is however an equally unique spiritual monument, and an important symbol of the historic, cultural and religious ties that bind the people of Arcadia together.

Conceptual Scale Model of the Round School. | Photo © leximata

The resurgent Greek culture of the 19th century was inspired by the glow of its classical heritage, yet emerged fatefully disconnected from it. The impetus with which Greeks used to strive to make sense of what constitutes justice, of what makes an ideal community, or what is good governance - all philosophical questions explored in Plato’s Republic - had become secondary to the medieval moral and civic conventions of the late Byzantine era, and its disastrous outcomes. By the 20th century, a Neo-Hellenic culture has taken hold, characterised by romantic reminiscence, counterproductive self-pity, blind revanchism, and endemic corruption. Inside this purgatory, a vicious circle of astonishing success is always followed by stupefying failure, in an unplanned state of permanent complacency that is always attributed to certain fantastical others. It is a moral decline that Constantine Cavafis alluded to in his poem “Waiting for the Barbarians”, and is without doubt the starting point of the country’s recent string of financial and political failures.

Breaking this craven mould, Takis Zenetos was the Greek modernist architect who demonstrated unbridled optimism and progressive vision through his work. He has a rightful place in my obscure pantheon, another important 20th century personality that epitomized the virtue of living up to one’s own high standards of moral and civic duty.

Round School top down view. | Photo © Dimitris Vosios

Agios Dimitrios (often referred to with its pre-1928 name, Brahami) is one of the most densely populated suburbs of Athens with a density comparable to Cairo or Seoul. The typical expedience and maladministration that characterized post-war Greece has left its indelible mark in the suburb’s architecture: its arbitrarily arranged streets define pocket upon pocket of unimaginative apartment blocks that connect to those of surrounding suburbs to form a veritable sea of concrete and tarmac. This is the result of the “flats for land” legislation of 1929, which enabled owners to give up their neoclassical houses in return for a flat or two in the uninspiring concrete tenements and high rises that soon began to blot out the quaint early 20c. suburban landscape. The desperate measure was initially brought in to manage the pressing housing needs of destitute immigrants from Asia Minor in the 1920s and 1930s. The 1.6 million displaced were joining a country of 5 million. This summary convenience was extended to solve later rapid urbanisation problems, such as the Axis occupation and its aftermath. Throughout the 1940s and 1950s, people fled the Civil War and the prospect of a hard life in their devastated villages and sought a better future in the capital, whose extant high density infrastructure had been equally ruined in a month of tenacious urban confrontation between Communist guerrillas and Government forces (the Decembriana of 1944).

The new architecture principle is educational autonomy, its curves disrupt the sea of high rise blocks that surround it. | Photo © Thomas Andreopoulos

This short term, anarchic character of Greece’s urban planning mentality was deeply troubling for Takis Zenetos. Born and active in Athens for most of his life, he must have witnessed the entire devastating process first-hand: the consequence of conflict in the capital’s urban grid, coupled with the inexcusable sloppiness of the state managing it. The occupation interrupted his studies at the National Technical University (the Metsovion), but in 1945 he moved to Paris to continue at the Ecole Des Beaux Arts under Otello Zavaroni. He was influenced by the order and principles of Modernist architecture in France, before coming back to Athens to practice in 1955. For the next decade, Zenetos designed and built sensational, distinctively Modernist factories, apartment blocks and private villas, always in partnership with his friend Margaritis Apostolidis.

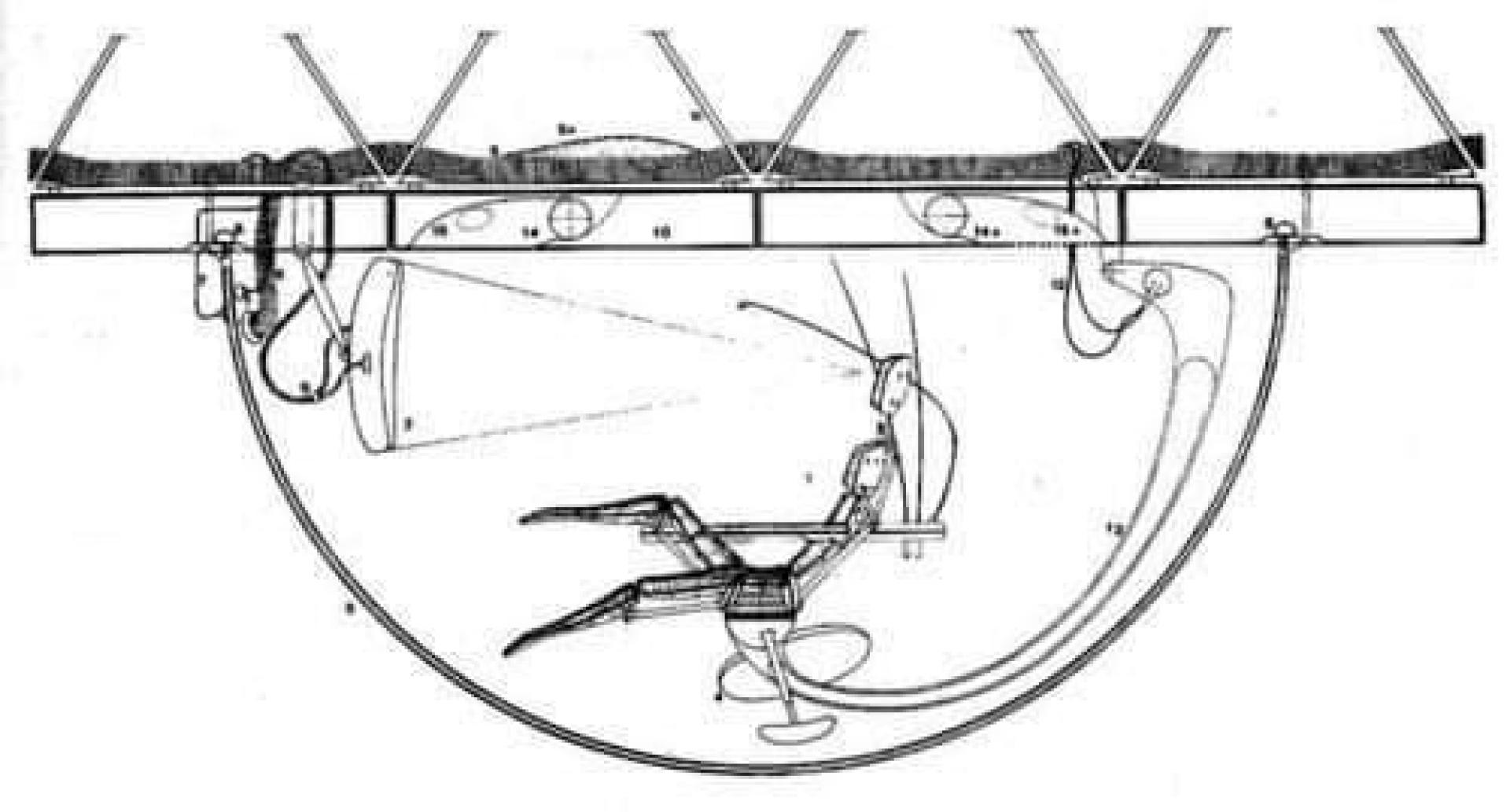

In 1962, Zenetos presented his theoretical concept of Electronic Urbanism founded upon his understanding that science and technology will revolutionize human living. He imagined the new social interaction and communication protocols of the future world; his ideas describe, in principle, what we know today as email, video calling and cloud sharing. His faith in the catalytic influence these would have in our daily lives was well ahead of its time, and informed his architectural designs. His “Furniture 2000”, a multimedia lounge chair for controlling the connected household of the future won a honorable mention in at the Interdesign 2000 competition in 1967.

Furniture 2000 | Photo via Tomorrows project

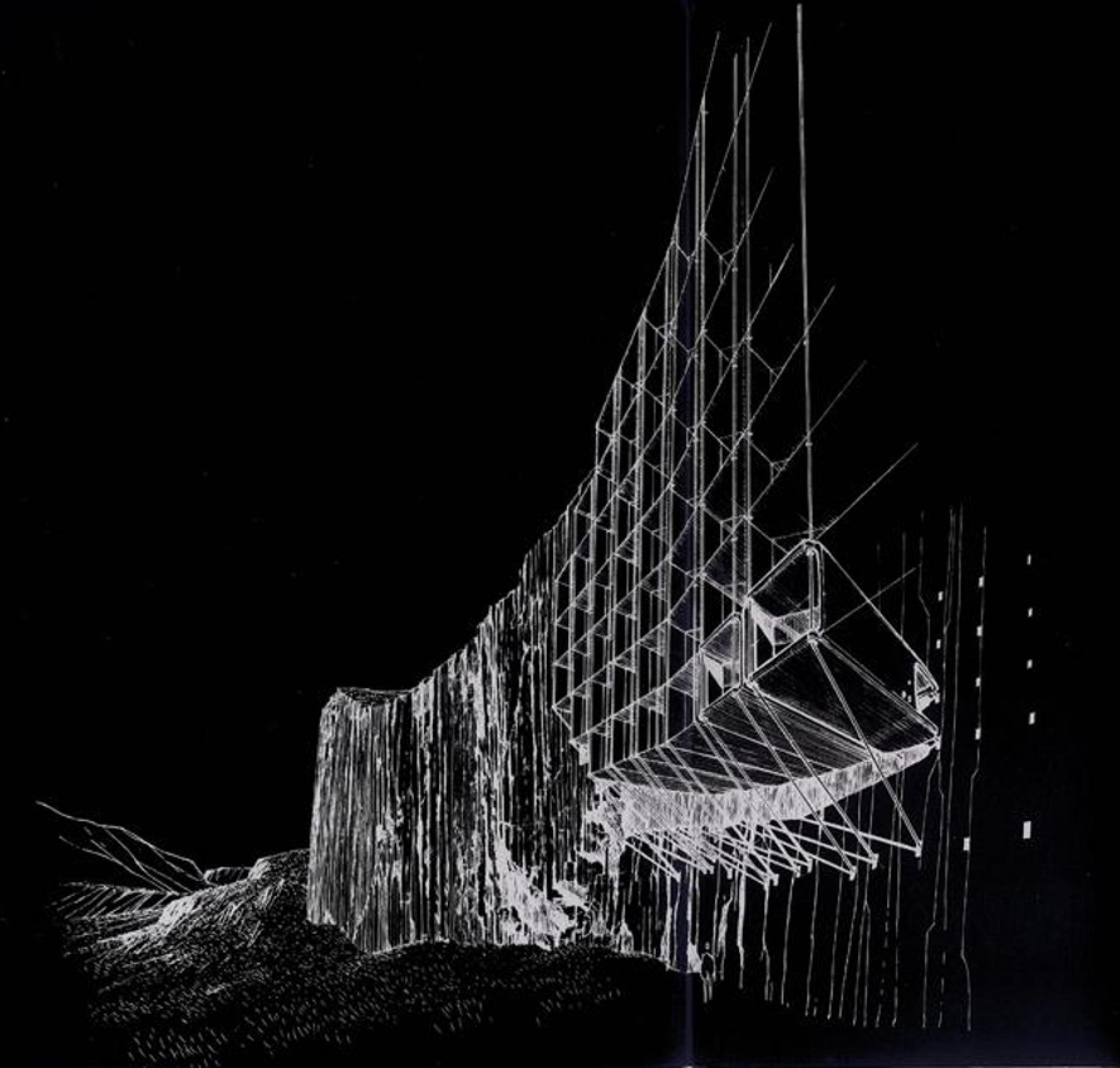

Zenetos envisaged futuristic networked cities, evolving around frameworks of massive, flexible cables. These web-like networks would solve the problem of urban regeneration once and for all, allowing the constituent components of the urban landscape - such as buildings, services, or amenities - to attach and detach, becoming replaceable parts of a whole that would easily adapt to the flow of an evolution driven by technology. At the same time, the natural environment would remain at ground level, unaffected. It would have been a landscape pure from infrastructure, with high-tech cities literally hanging from the skies.

Takis Zenetos The Hanging Hotel (1967). | Photo via Mascontext

We can take a glimpse at this unconventional approach, the capacity to innovate, his desire to disrupt the grim post-war urban architecture of Athens at the Round School of Agios Dimitrios. The Modernist rotunda is perhaps his most ambitious surviving work, and the one that still remains closest to his vision – since many of the private residences and factories he designed have either been demolished by municipal authorities on a whim and without consultation, or significantly altered. The reason the school survives mostly unaltered can be credited to the way Zenetos infused the built structure with his vision.

But there’s also a visual message. A new language emerges in the refined way the Round School’s Modernist curves disrupt the sea of high-rise blocks that surround it. This is an empowering environment of uniqueness and self-determination, and an anti-hierarchical symbolism designed to unclutter the young minds from the institutional architectural cues they are confronted by in educational spaces. It’s a bastion against the inner-city uniformity of Agios Dimitrios, of any Greek town. By raising the bar well above the Ministry of Education’s typology of schoolhouse ergonomics, Zenetos created an outstanding building that facilitates communication with its occupants, and a space that attunes them to the concept of individuality. His message hasn’t been lost to many generations of students, many of whom still reminisce of their journey in learning at the Round School with feelings of immense pride and appreciation.

The Round School is a personal statement, a defiant stand against an overwhelming standard of mediocrity. | Photo © Thano Baf

There’s no other Greek school like it, either before, or after this veritable piece de resistance. It is different, inspiring, a beautiful affront to an entire country’s post-war urban architecture manual. It is the product of a vision lost, but not entirely forgotten. Zenetos grew increasingly alienated by the lack of appreciation for his futuristic vision by the establishment. Frustrated by his inability to influence the change he believed in with all his heart, he took his own life in 1977.

Evan Panagopoulos is the urban storyteller behind alternative site Explorabilia. He’s an avid fan of Brutalist and Mid-century architecture, likes engaging with abandoned spaces and obscure history, and expresses what he’s passionate about through writing and photography. His Forgotten Greece tour is available to book on Airbnb and Atlas Obscura.