Emblem Of A Better Germany?

In 2014, at the 14th Venice Architecture Biennial, Alex Lehnerer and Savvas Ciriacidis placed the armoured limousine once used by then Federal Chancellor Helmut Kohl in front of the German Pavilion.

It was a black Mercedes-Benz car with its famous star that added the air of a different era, the Federal Republic of Germany before the fall of the Wall, when its capital was Bonn on the Rhine River in West Germany, and not Berlin. Placed before the steps of the monumental façade of the German pavilion, once build as the Bavarian pavilion and then decisively altered by Nazi Germany in 1938, every German visitor would read this car as a sign, an emblem of what came to be known as “Made in Germany”, high quality cars, machines, and other industrial goods that were seen as responsible for the so-called “Wirtschaftswunder” (economic miracle) after WWII, the economic rebuilding of West Germany.

On the one hand, this car is a desirable object, vintage and expensive. In my family, you knew you had made it when you could afford a Mercedes-Benz. You could tell, when my parents bought their first Mercedes-Benz, they were full of pride. And they still drive the same car and feel the same way about it, although now it’s a rather old car.

On the other hand, you could also read the continuities of 20th century German history into this juxtaposition of car and pavilion. Because what is the link between the Nazi façade and the later car? You might answer this question with the seamless integration of Nazis in German politics and business and the financial gains of many German companies (including Daimler-Benz) during the Nazi period thanks to forced labor, expropriation, and simple opportunism. The juxtaposition places you, at least as a German, between guilt and pride, haunting memories and desire.

Adjacent to the left of the big front door of the German pavilion in Venice, the visitor was greeted by an elegant section of a roof jutting out above a much smaller door. It was a hint that the interior of the pavilion was taken over by another structure, a partial replica of the former Chancellor’s residence in the former capital of the country formerly known as West Germany. A somewhat nostalgic remnant of a bygone past, a country and political system that were fundamentally altered by the fall of the Berlin Wall and the reunification of Germany. It was the Germany I was born into, with Bonn being the capital until 1999 and the Chancellor’s residence – or Kanzlerbungalow (‘Chancellor’s bungalow’) – constantly in the news. As much as it was nostalgic, Lehnerer and Ciriacidis’ pavilion had an uncanny feeling to it. Inside and outside were suddenly called into question, different times collapsed into each other, with the democratic bungalow inserted into the Nazi pavilion. Or was the story told more complex than that, as with the car parked in front of the pavilion? The story was, for sure, one about architectural representation.

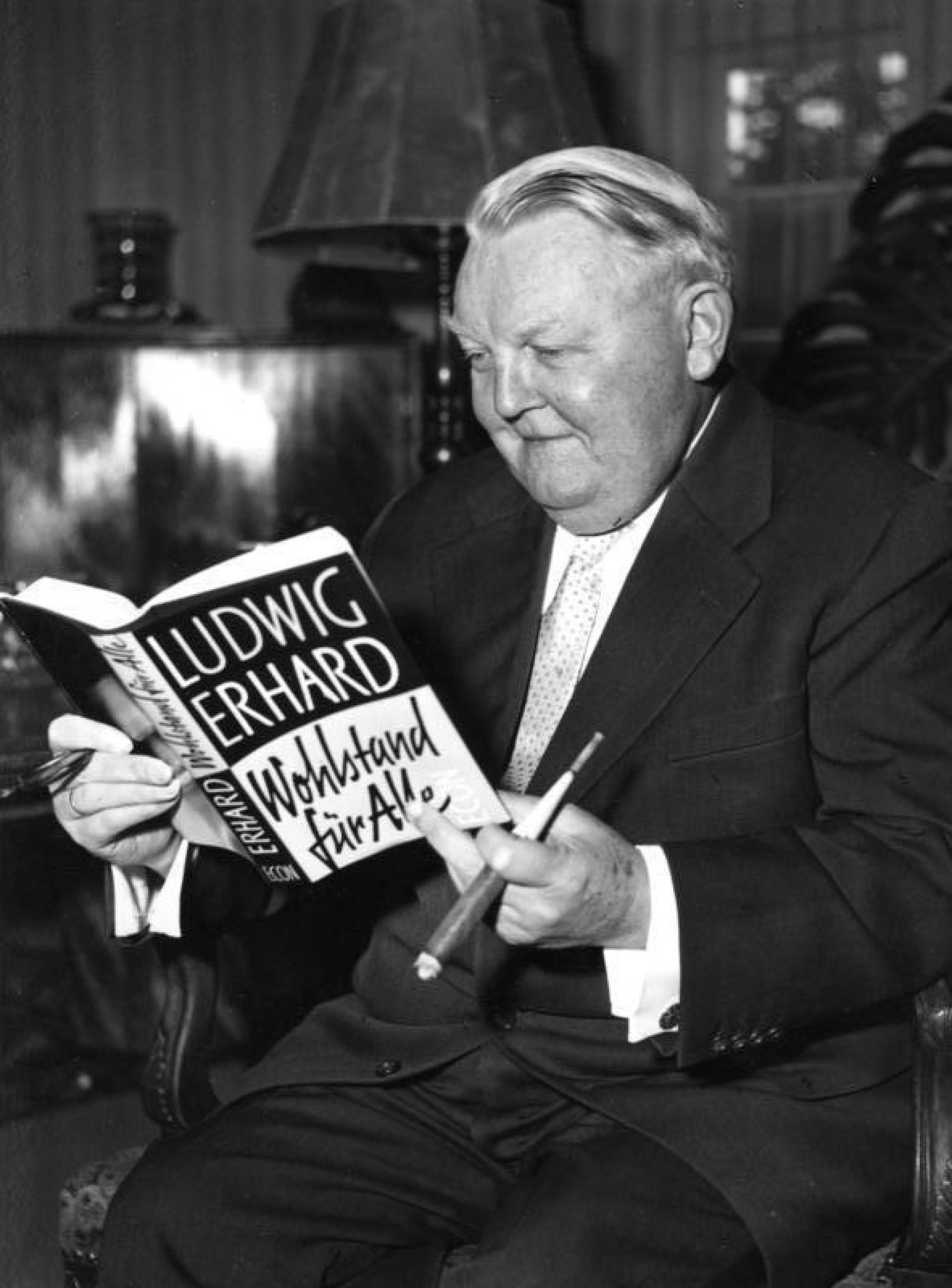

The Chancellor’s bungalow was built in 1964 by the architect Sep Ruf for Ludwig Erhard, the second Chancellor of West Germany. Erhard was the German politician who stood like no other for the ‘economic miracle’ of West Germany after WWII. As the Federal Minister of Economic Affairs under Chancellor Konrad Adenauer from 1949 until 1963, when he became Chancellor himself for three rather unlucky years, he promoted what he termed the social market economy and gained widespread popularity with this economic concept. Although Erhard worked for the German state as an economist during the war, he rejected Nazism and was in contact with members of German resistance groups. It seems fitting therefore that as Chancellor he hired the fellow Bavarian Sep Ruf to design the new Chancellors residence in Bonn. Ruf was known for his functional designs in the tradition of the Bauhaus and older modern architects, who had mostly emigrated during the 1930s, like Ludwig Mies van der Rohe. Ruf’s elegant bungalow in Bonn payed homage to designs of the Bauhaus and Mies in particular. The latter’s Barcelona Pavilion, the German Pavilion at the 1929 International Exposition in Barcelona, has often been mentioned as a reference.

Dining room of the bungalow of the Chancellor in Bonn.

By 1964, Ruf had already worked for the federal government several times. Together with another modernist architect of the postwar period, Egon Eiermann, he had for example built the German pavilion for the world fair in Brussels in 1958. He was, thus, well informed about West Germany’s representational needs. The Chancellor’s bungalow spoke not only of the Bauhaus and the better, modern Germany that was supposed to be represented by buildings in its tradition like those of Ruf, Eiermann and others, but it also established a clear link to modern architecture internationally. Looking at the bungalow, some might be reminded of the famous Case Study Houses at the West Coast of the USA. After all, it was the declared aim of West German politicians to make the Federal Republic part of the Western political sphere (‘Westbindung’, or policy of the alignment with the West). I would guess that these two aspects, the tradition of a better, modern Germany and the alignment with the West, were first and foremost represented by Ruf’s bungalow in Bonn.

The second Chancellor of Germany, Ludwig Erhard.

The third Chancellor, Kurt Georg Kiesinger, took over from Ludwig Erhard in 1966. He was a former member of the NSDAP and disliked the Chancellor’s bungalow for its functional, ‘cold’ design. He had many things altered before he moved in and brought with him antique furniture pieces in stark contrast with Ruf’s modern architecture. Most of the other Chancellor’s after him agreed with Kiesinger’s view on their official residence. They were looking for something more comfortable and cosy (gemütlich). Under Chancellor Helmut Kohl the interiors had changed so fundamentally that it was hard to still see Ruf’s designs behind thick layers of carpet and bulky sofas and chairs. Not to speak of the new 1980s glittery lighting. Although partly preserved in the original building in Bonn, these alterations, additions and layers were not present in Venice.

Prince Philip, Queen Elizabeth II and the ex-Chancellor of Germany Helmut Kohl front of the bungalow of the Chancellor in Bonn

It was a clearer picture or juxtaposition that Lehnerer and Ciriacidis drew. Only the brief blaze of fire in the Chancellor’s fireplace could have been something of a reminiscence to the other, the not-so-modern, not-so-open, cosy Germany that gathered around home-and-hearth. The Germany I grew up in. Just like the Mercedes-Benz, a fireplace was something quite desirable for the generation of my parents. You had to have one. And now, decades later, my parents even installed a new one. As if you couldn’t or wouldn’t want to live without it. Herman Miller’s Eames Collection that Erhard chose for his initial version of the bungalow at the River Rhine might have always been too expensive for most Germans, but they also represented a certain idea of Germany, like the whole bungalow an internationally oriented, better Germany – and not necessarily the real one. I wonder, does the real, and not the ideal, ever get represented? It might be an interesting task for a future German pavilion at the VAB.

The bungalow of the Chancellor in Bonn.

West Germany claimed the Bauhaus as its heritage since the 1950s, through the founding of the Bauhaus-Archiv in Darmstadt in 1960, countless exhibitions and books and buildings seemingly in its tradition (there were similar efforts in the GDR a little later). 2019, the year of the centenary of its founding, saw the Bauhaus at the height of its representational instrumentalization, it had become a major part of German cultural diplomacy. Yet, the Bauhaus has oscillated between national claims and International Style even before it was closed by the Nazis. This oscillating reception of the Bauhaus was crucial in making sure that the Bauhaus would continue to be productive until today. Looking back in 2020, the German Pavilion at the 14th VAB is also a vivid illustration of the complicated history of the Bauhaus and Germany.

Florian Strob is an author and curator in the fields of architecture, literature and contemporary art. He holds a B.Sc. in Architecture from the Technical University in Berlin and a PhD in Medieval and Modern Languages from the University of Oxford. His main research interests are modern architecture, modern poetry and experimental prose, and the connections between built spaces and text. Florian currently works at the Bauhaus Dessau Foundation, where he curated the exhibit “Bauhaus Buildings Dessau: Originals retold”. For this, Dessau’s Bauhaus buildings, facades and interiors are on exhibit. They have been given a new and coherent narrative through an exclusive series of video clips which set historical images in motion using 2.5D animation. He also organized the international conference “Collecting Bauhaus” in December 2019. He is the head and curator for the Bauhaus residency programme 2020-2022, which invites artists and writers to live, work and exhibit in the historic Masters’ Houses in Dessau. The most recent exhibition in this series, “Gropius House || Fictional. Inge Mahn and Sujata Bhatt”, is on show until 20 September 2020. Most recently, Florian published “Bauhaus Dessau Architecture” (Hirmer 2019), including new photographs by Ostkreuz photographer Thomas Meyer. He is author, editor and contributor of several other books, including “Hiatus. Architekturen für die gebrauchte Stadt” (Birkhäuser 2017) and “Schreiben und Lesen im Zeichen des Todes. Zur späten Prosa von Nelly Sachs” (Winter 2016).