Human Architecture Needs A Dissident Instinct

Ljubica Slavković and Iva Čukić planned this interview questioning the meaning of the exhibition Toward a Concrete Utopia: Architecture in Yugoslavia, 1948–1980 in MoMA. The talk with Dragoljub Bakić presents a story of love, devotion and architecture of the inseparable Yugoslav architectural tandem Dragoljub and Ljiljana Bakić.

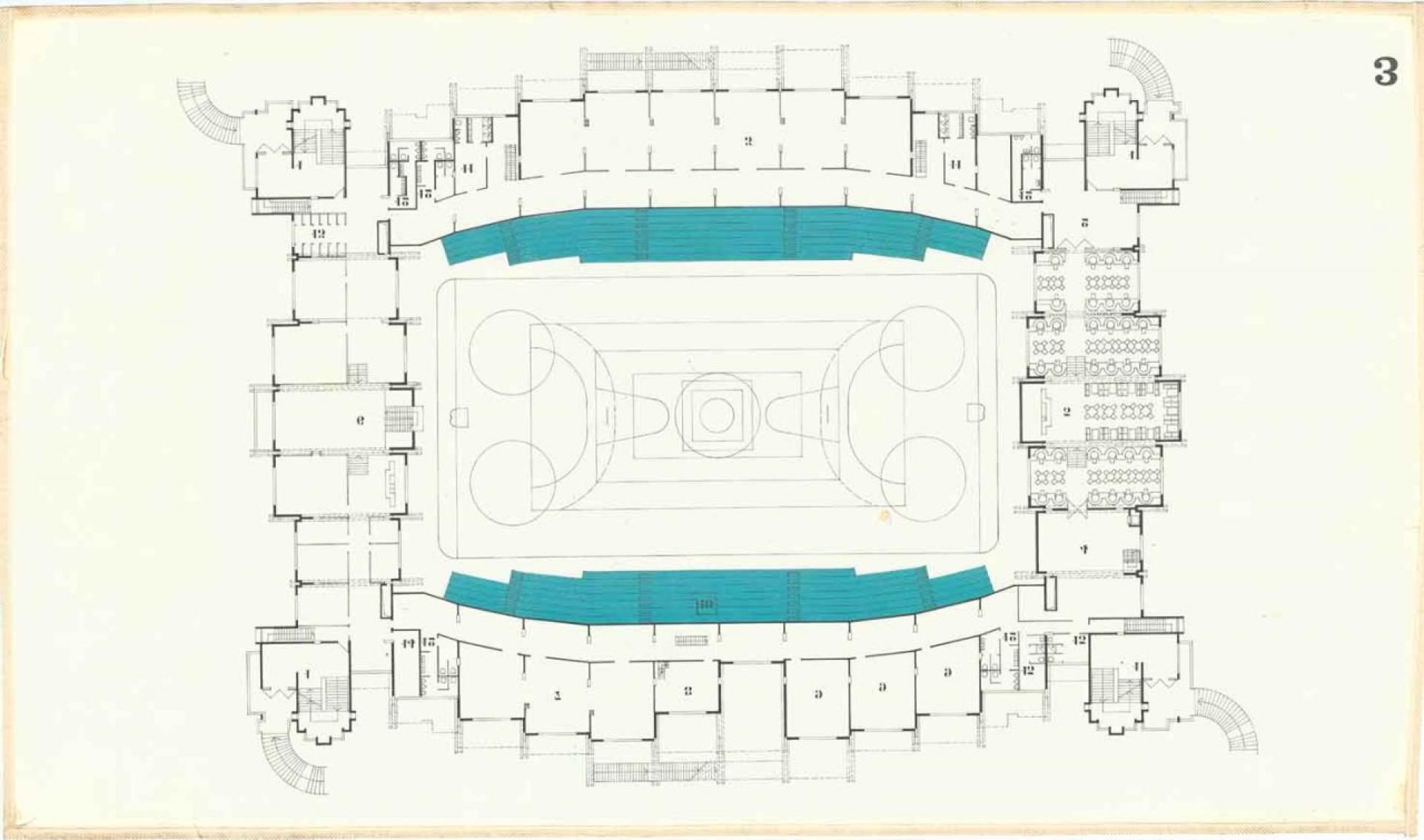

Pionir Sports Hall in Belgrade. | Courtesy of Dragoljub Bakić

HOUSING SETTLEMENTS

Before meeting Dragoljub we have passed through the settlement that the couple designed. After reaching the beautiful house in a row with a garden and a view over the Danube river, we were completely blinded of all this beauty.

DB: It is interesting how there is now a curiosity in what we did in the era of socialism. This discovery started with Rem Koolhaas, who saw what Energoprojekt built in Lagos, Nigeria. During the time of socialist Yugoslavia, we did not have an Iron Curtain like the other Eastern European countries. What is obvious is that we had other types of restrictions that did not allow to be discovered what was happening here. We were signed off as an eastern block, at least as far as the West was concerned.

Dragoljub Bakić, Ljubica Slavković and Iva Čukić in a garden in the Višnjička Banja neighborhood in Belgrade.

Our architecture developed through cooperation with each other and also under the Balkan Association of Architects. Good architecture was made here. I think that we developed a great part of the Modern and Post-Modern architecture.

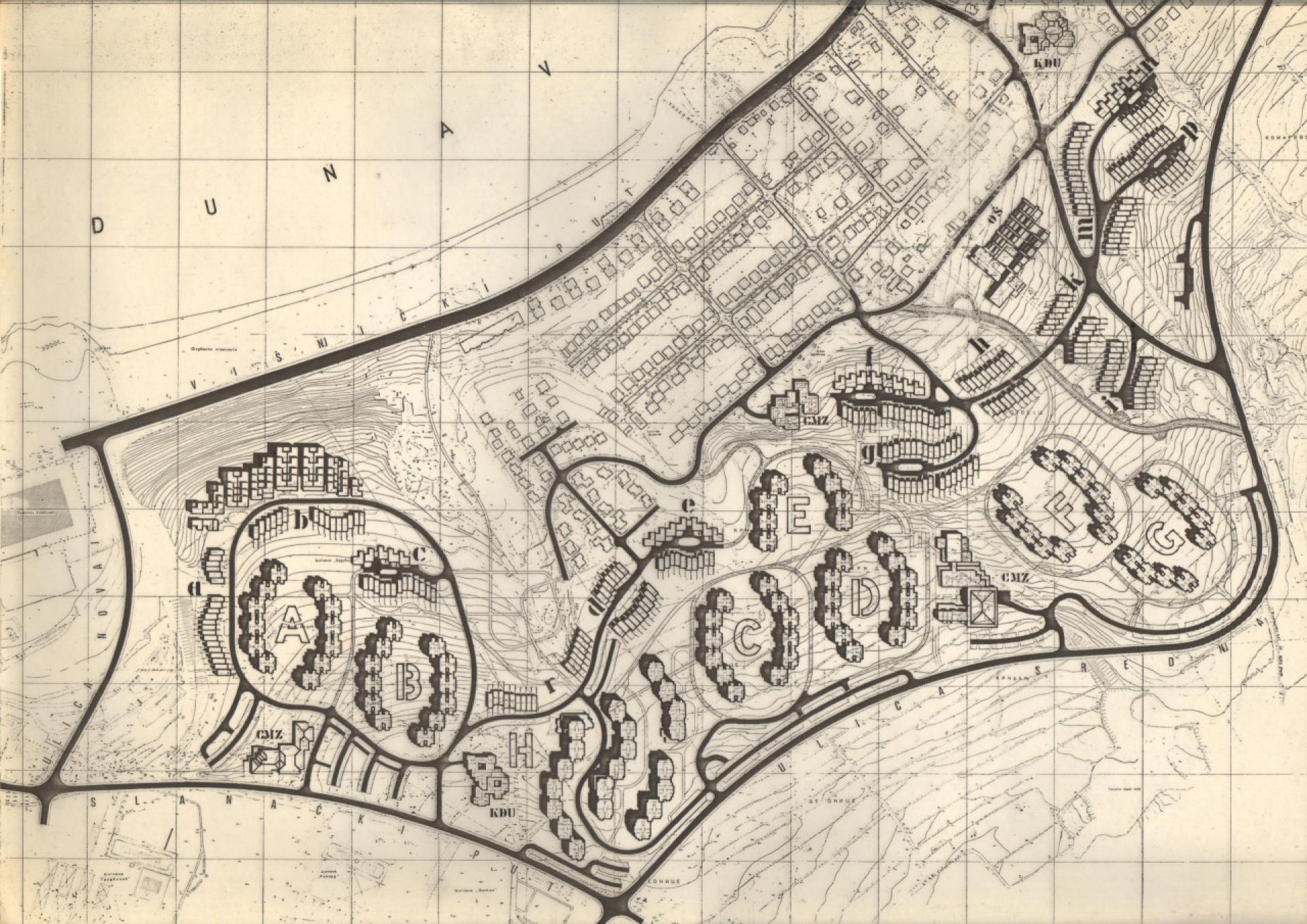

Plan for the residential area Višnjička Banja. | Courtesy of Dragoljub Bakić

During the period of Yugoslavia, a lot of apartments were built; housing construction was higher than it was in the West. Especially, because we had a political project with the idea of the right to an apartment. It was under a certain level of control with specific criteria and sizes of flats. In the socialist system the needs of people were somehow equalized. Both a faculty professor and a worker received the same square footage, although the first one needed a library and the other a big kitchen, but it was all averaged.

Višnjička Banja housing in the 1980s. | Courtesy of Dragoljub Bakić

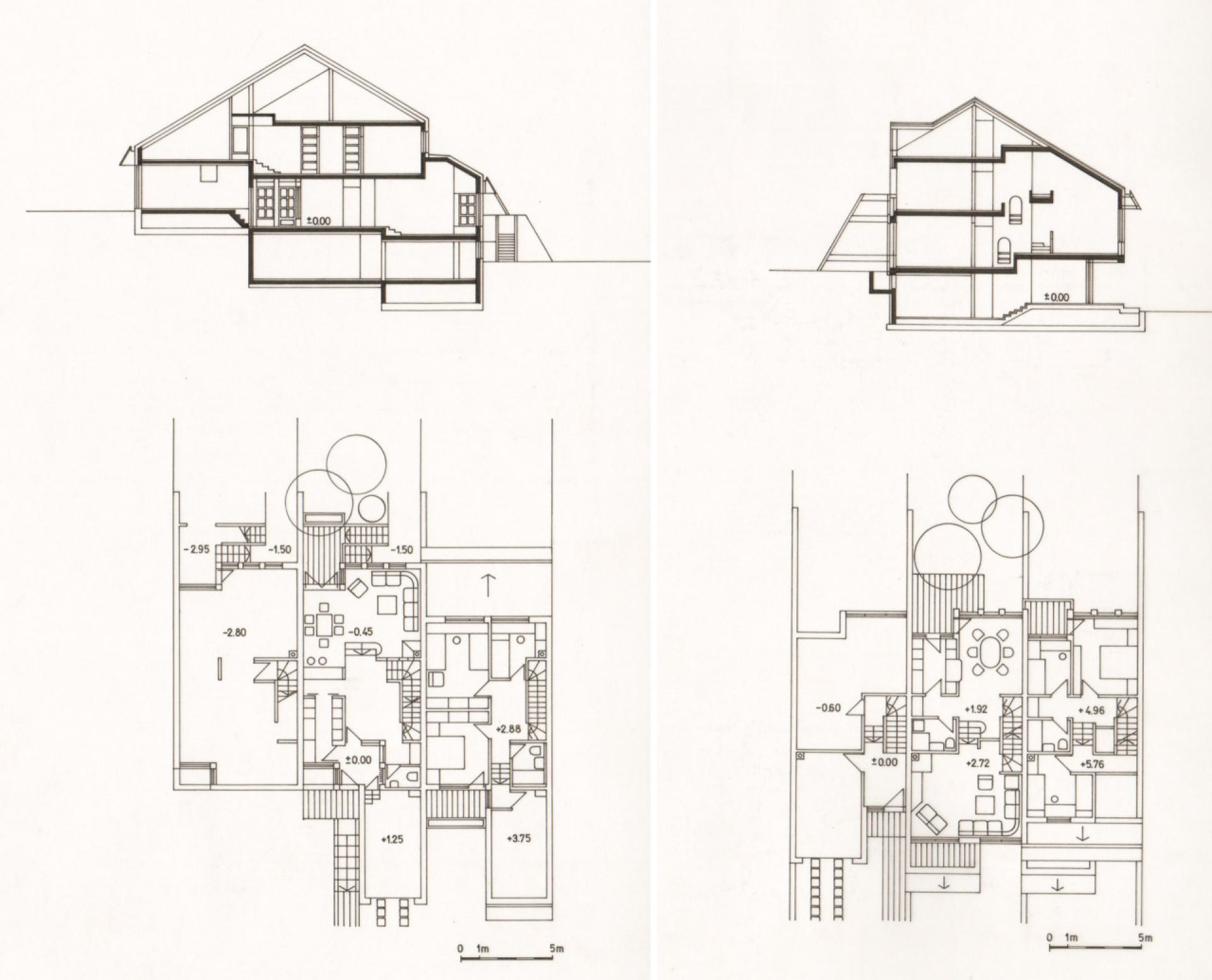

When the time for designing Višnjička Banja came, the residential area where we have lived for the past 35 years, we had very strict conditions. However, we were protected by the General Plan of Belgrade (GUP) from 1972. Urban laws were well respected in the time of socialism and could not be changed as today how any one likes. Nobody respects anything today. Višnjička Banja was supposed to be another Dedinje, a fine living area where Belgrade will give vent to large conglomerates such as New Belgrade. The predicted density was 90 inhabitants per hectare. Such density created a garden settlement and the plan foresaw individual houses and villas in set in greenery.

Housing in greenery at Višnjička Banja. | Courtesy of Dragoljub Bakić

But still, besides the individual houses, the settlement has also multi-dwelling units?

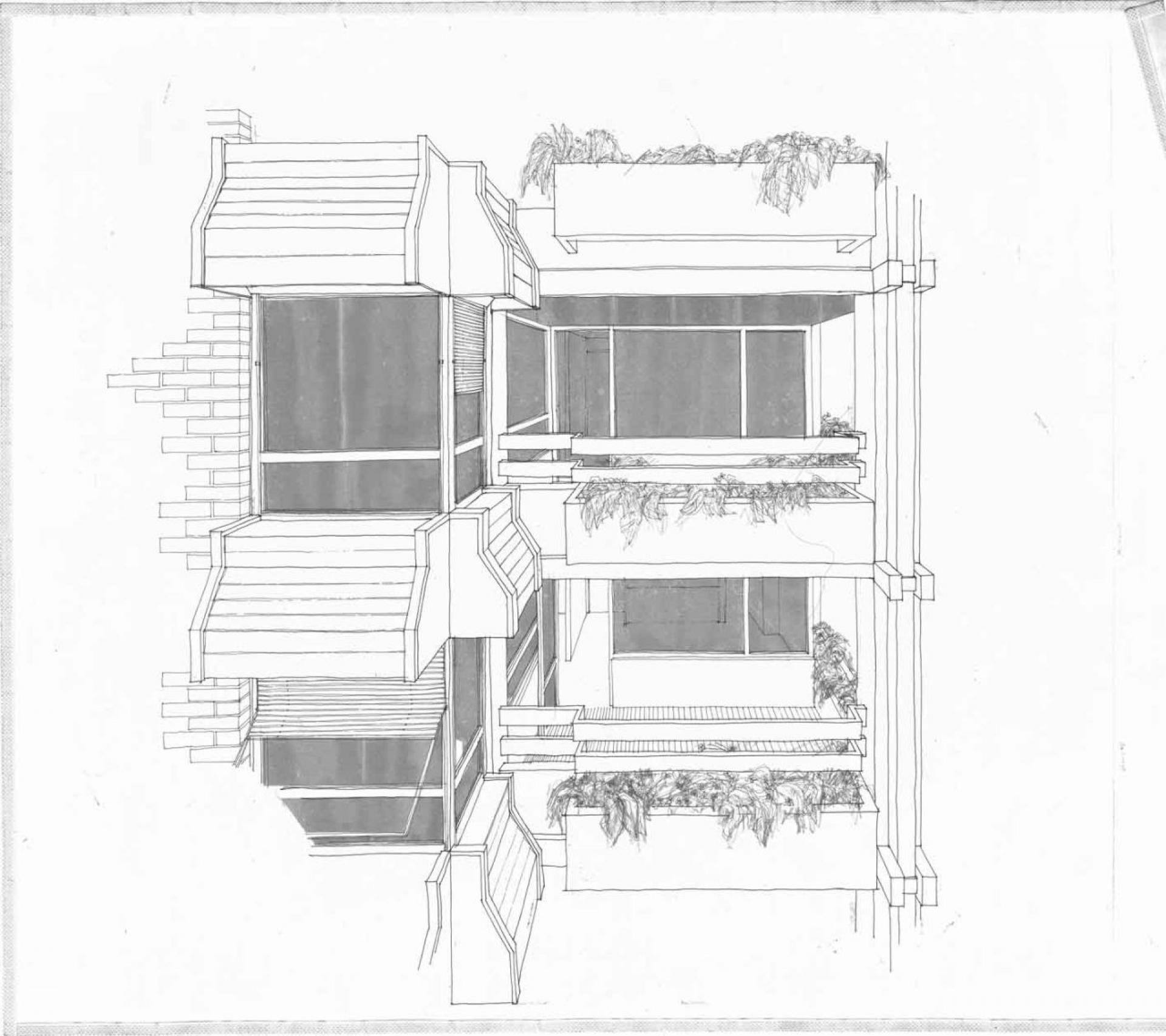

DB: The changes that followed and the transition to socially oriented housing construction led to designing for the housing needs of the workers from different companies in the municipality. We proposed a system of low-rise houses to preserve the natural environment and take advantage of the space. Instead of making a multistory building we laid the building down. We argued for more square meters than planned, because it only made sense with the proposed density, and we designed the apartments with the impression of individual houses. They all have terraces with a view of the Danube and open spaces next to the kitchen. We were thrilled when we first came here as everything was completely bare; nobody wanted to build because of the exposition to the Košava wind. Today the location is completely different as pine and cedar trees planted by residents thrive well. I planted the pine tree next to you 35 years ago and there was another one, which I had to cut because it was too close to the house. These pines and cedar trees have completely changed the microclimate, and Košava now skips the site.

The whole settlement of Višnjička Banja looks out to the Danube, instead of facing the sun and south creating transversal cross ventilation and visions in all apartments. | Courtesy of Dragoljub Bakić

You have lived here since the construction period and the moving into the settlement. How have things changed here over the past 35 years?

DB: The settlement consists of buildings in a row, high buildings with apartments for workers of the company, and houses in rows that were on the market through one of the then five large-scale housing cooperatives. A very interesting social layer has moved in here - at least 15 architects from Energoprojekt, directors, actors, writers, chess players. We hung out together back then as we still do today. We gather almost every week, for a hot brandy at my place, or we meet at his house, her yard, we live together in the settlement. We believe that this way of living has contributed to bringing people closer. The neighborhood relations were developed because of the low density of the urbanism. We consciously designed them in the form of a horseshoe, so each building has its own yard, a sloping terrain with children’s playgrounds or benches. Where neighbors can meet, now I can see that someone has planted some flowers.

In Višnjička Banja’s neighborhood a Scandinavian architectural atmosphere was implemented. | Courtesy of Dragoljub Bakić

The neighborhood spirit has been developed. The measure of success for an architect is the measure of client and investor satisfaction, and in general, that is the essence of our call. In these 35 years 50% of the population structure has changed, many have died; a lot of families sold their houses and left because of the war at the beginning of the 1990s. Initially, there were no fences here but people began to encircle their houses because of pets. The new tenants are not interested in socializing, or even greeting. Our new neighbor has put up a metal fence and grids on all his windows. You’ll see this on many homes. An interesting sociological phenomenon is going on and it also speaks about the sociological structure of society; what we have become, who we are, and against whom we fight.

Architects have social coordinates, and the society and its development determine the coordinates in which you create as an architect. But also, as an architect, you create a society. And that is not easy. You said that at the time of designing Višnjička Banja, you were protected by the GUP, but the execution and settling in the early 80’s were significantly hampered. Why?

DB: What we went through with the Višnjička Banja project. We moved into the house in 1983-84. When those in positions of power realized what was built here, they accused us of destroying the socialist morality. All audits passed here, we got all the permits, but as architects, we were branded. It turned out that Višnjička Banja became a new Dedinje, a fancy living area, but there were no people in position here. Only us citizens. And our keys were confiscated, it was a big affair. When the settlement was built and we moved in, we become victims of a great affair, to the extent that we were expelled from Energoprojekt.

The project of Višnjička Banja was accepted by the city and municipal authorities and was known as quality living made with cheap but quality brick and tiles produced by Energorpojekt. | Courtesy of Dragoljub Bakić

At the beginning of the 1980s, Energoprojekt pulled all its forces towards a huge project in Iraq. Only the guards were left here, and construction completely stopped even though people had already paid their homes in advance. Years passed, things changed, the dollar and dinars ratio changed, the money was gone, but the houses were unfinished. At that time, we were working on a project in Harare. When we finished our project in Harare, we were invited to return to Belgrade. The contractors asked us then to increase the square footage in the whole settlement so the people who had already paid for their houses would have to pay more. Of course, breaking the architectural ethics was not an option; we refused to do such a thing. All of a sudden, they declared us enemies to Energoprojekt. What we passed through was recorded by a bunch of newspaper articles. Fortunately, there were also honest people, both among the judges and colleagues, so in October 1984 we returned back to the company.

But what happened with the tenants of Višnjička Banja and the demands to pay more money for the houses? How did people move in here?

DB: By June 1983, after Energoprojekt confiscated the keys and asked for large surcharges, the tenants made a decision. The first 110 of them made a line with their cars on the Slanački road in the early morning at 6am. They all burst into the village, broke doors, changed locks, and moved into their homes. They saved us our key, as we were in Harare at the time, and when we came, they gave it to us. Our door was the only one, which was not ruined. That’s how people moved in here.

And this is how the community spirit emerged even before settling in the area. I believe that is because all of your work is done with a strong sense of building a more humane society through, or with architecture.

AGAINST CLICHES

All your creativity is permeated with a strong awareness of the ultimate user and the impact of architecture on the lives of people, as well as a struggle through architecture for a more humane society. That is what Mrs. Bakić perfectly illustrated in her book, “Anatomy of B & B Architecture”, while presenting your design principles.

DB: We always had a dissident instinct against every kind of dictatorship and ruling clichés and we were constantly struggling. In the Nova Galenika settlement, which we designed in 1976, we were first to introduce slanted roofing. We had big clashes, for example with the president of the Zemun municipality. We had to reiterate that this roof is cheaper than a flat slab, which at the time had to have 17 layers in order to not leak. And would always later crack and leak water. But we manage to do it even so that after Nova Galenika, a new regulation was made that flat roof terraces had to have slanted roofs.

Drawing for the Nova Galenika settlement (1976). | Courtesy of Dragoljub Bakić

The basis of Nova Galenika was the natural asymmetric scattering of the solitaire in the vertical sense, connecting the solitaires with their horizontal openness into organic groups. | Courtesy of Dragoljub Bakić

Your design principles and creative expression are highly inspired by the architecture of Scandinavia, by the relationship with nature, local materials and the quality of space. We see that in the settlement of Višnjička Banja, and in Galenika, but also through your entire relationship to space and materials.

DB: A great impact was the year 1970, which we spent in Finland, in Alvar Aalto’s Bureau. This was possible because of Energoprojekt. And it was a beautiful bureau in Helsinki. We showed them what we had done in Kuwait and they loved the slides and were interested in cooperation.

Collective Housing in Kuwait (1966) by Ljiljana Bakić and the office Said Breik & Marwan Kalo. | Courtesy of Dragoljub Bakić

There, they lived in row houses, and we were so enthralled by this spirit that we disregarded the latitude and longitude, we wanted to pass something of this spirit in architecture to Belgrade. We were deeply convinced, almost obsessed, that the projected environment could raise the level of living awareness and change people’s habits. But it turned out that in addition to geography, a little spirit on this subject was also needed. Višnjička Banja has shown that it was the correct way of living, very human with the socialization of neighbors, but afterwards it did not cast roots. In a whole series that could have followed this, people began building huge weekend houses.

Why Aalto, how did you even reach Finland in the 60s of the last century from Belgrade?

DB: Because we had a great professor, the architect Nikola Dobrović. He used to put on a bow tie and a black suit when he was teaching about Wright. A great influence on us had also the Hansaviertel in Berlin, where the ruins after the bombing were cleaned and where Oscar Niemeyer, Alvar Aalto, top leading architects of that period were engaged. We studied this cases because we could learn from their housing construction.

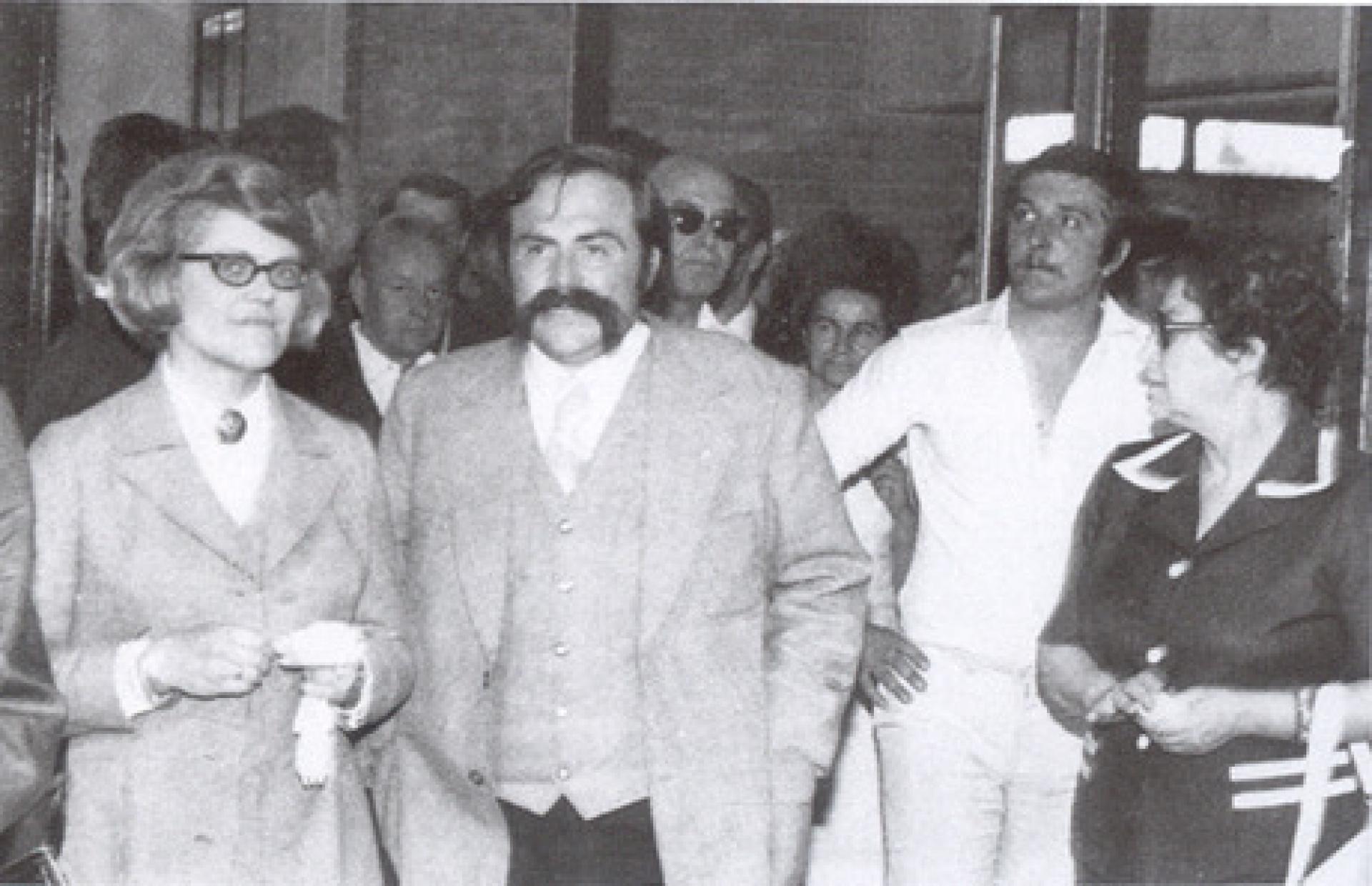

Ljiljana and Dragoljub Bakić at the opening of the Pionir Sports Hall in Belgrade, 1973. | Photo via CAB

In Yugoslavia we stepped out of many frames, which was possible because of the Non-aligned Movement. In the world we were recognized and evaluated in such a way. At one point Energoprojekt worked in 45 countries and it was at the very top of the construction companies in the world. The West knew about Tito and knew us through Tito, but they did not know us through architecture.

One of your cult projects and facilities, at least in Belgrade’s life, is the Pionir Sports Hall.

DB: The design and performance of the Pionir Sports Hall was very interesting. The mayor Branko Pešić was a boxer and he wanted to organize the European Boxing Championship of ‘73 in Belgrade. As Belgrade didn’t have a sports hall at that time the building began in that year. The 25 May Sports Center by Ivo Antić was built. While Antić’s parallel piped roof was constructed we designed and built the entire Pionir. In nine and a half months we did both the project and the construction, and we could not do it differently than to make it prefabricated. We had a group of genius construction engineers in Energoprojekt.

For the Pionir building 90% of the structure was done on the ground and then raised. | Courtesy of Dragoljub Bakić

A year before the championship, seven large construction companies were invited to present their conceptual design and construction cost. We had about seven days to come up with the project, cost and time of construction. But then, we were also 32 years old, youth-crazy and as we say, could do anything. Energoprojekt got the job, and we got going. It was done so quickly, and the hall became a cult place for Belgrade sports.

Floor plan for the Pionir Hall. | Courtesy of Dragoljub Bakić

The task was that the hall should also serve for hockey, which means a fence that in turn led to steeper seating. Much later, a separate Ice Hall was created, which we consider to be our best project. But Pionir’s stands remained unusually steep, which made it a true home for fans. All of our clubs like to play there, the viewers, supporters, inspire them. They are their sixth player, with steep seating like that; they are almost with the players in the field! And those construction beams are five centimeters thick. The Energoprojekt’s construction engineer Vlada Vračarić was a total genius.

The Ice Hall. | Courtesy of Dragoljub Bakić

Why do you consider the Ice Hall as your best project?

DB: First of all, we consider it to be best fitted in its surroundings. We took off one side of the seating stands because we came to the very street. We did not have room for a two-sided auditorium, and this one-sidedness gave it character. But that roof, that used to be blue, and the way it fit in the environment, that is our cult image.

The cult image of the Ice Hall. | Courtesy of Dragoljub Bakić

TEAM WORK, HOME AND ABROAD

The Pionir Hall is Ljiljana’s and your first jointly done building, and many more followed.

DB: We have been working as a team for 40 years. We saw that in Finland - many teams had two or three members, and often there were teams of architects that were spouses. We met a lot of them, great Finland architects that were spouses who worked as teams. With time and experience, you start to think similarly, you begin to synchronize. Of course, you do not argue a lot. Well, we argued a lot, but I always gave in. We were lucky to work a lot abroad. There were a lot of projects that were not constructed, and that’s a shame.

Spouse’s sensitivity established over the years creates understanding of each other’s work. | Photo by Rade Kovač

If you seriously treat the importance of given conditions and conditionality, if you establish a certain level of ethics, of your calling, if you treat with equal importance both the outside and inside, and the facade is not the only importance to you, it was always important to us and what is inside and the relationship towards the surroundings, then it all becomes very natural. Some things you do not have to always start over, they are known. Ljiljana was a well-known mathematician at school, she easily drafted and did everything else, and so was I. But I think that the first violin was always Ljiljana.

We do have our own individual projects, we didn’t always work together. Then came the time when I had to deal more with organization, management, especially in Harare. Ljiljana was more burdened with designing, and me chasing after clients, getting payments, getting work.

You’ve done a lot of projects, but there are a lot of those who just stayed on paper. Which one do you particularly regret not being made?

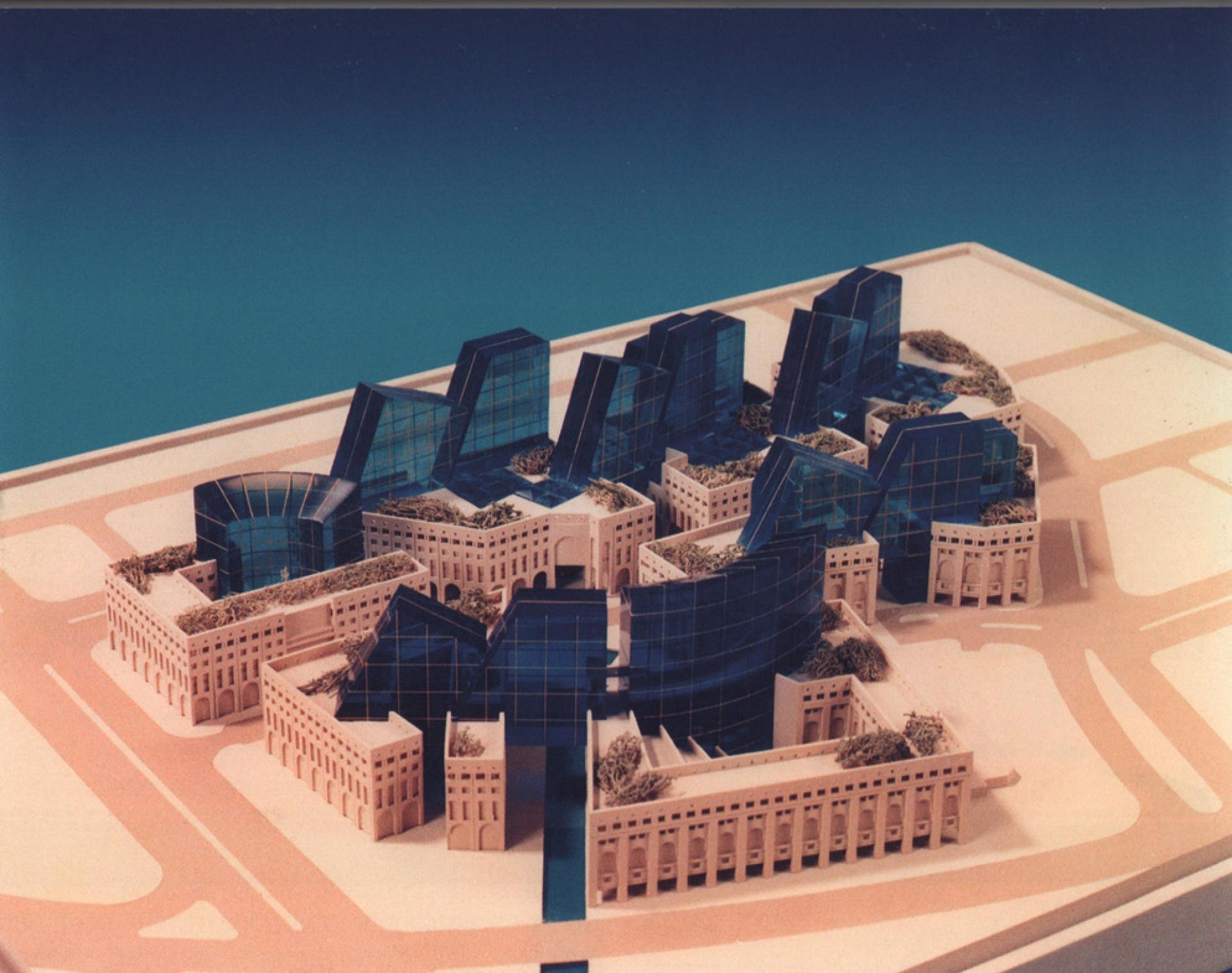

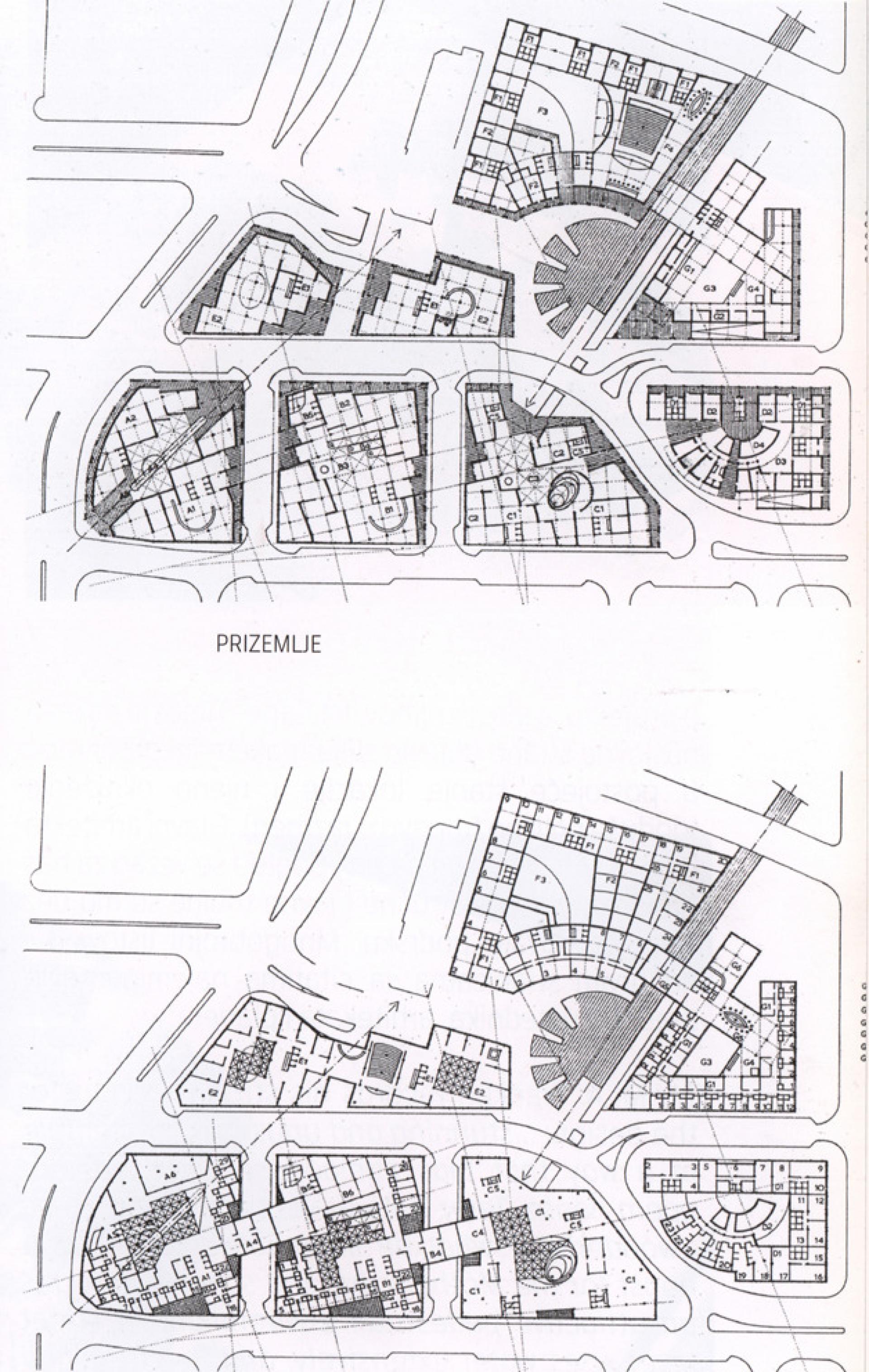

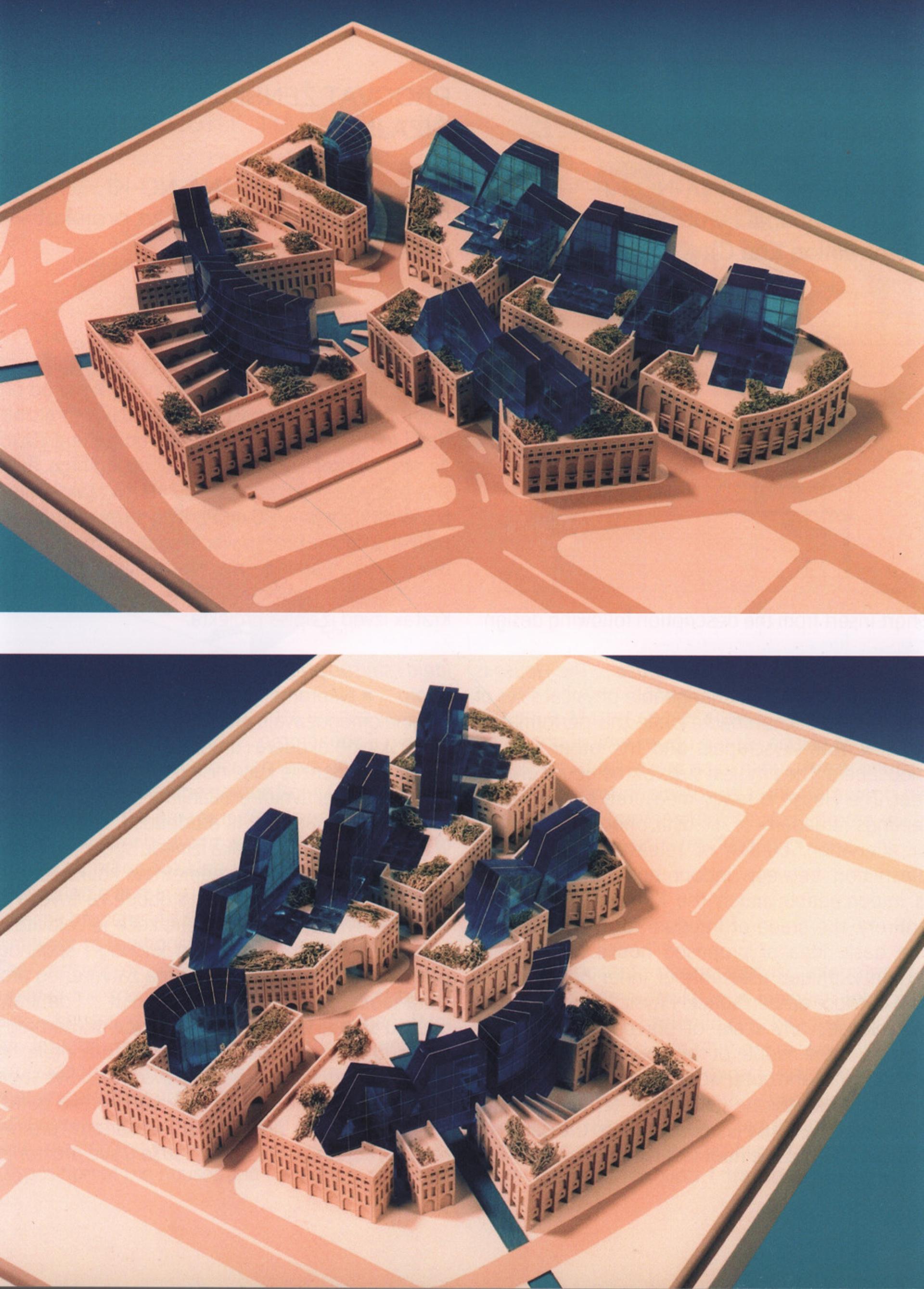

DB: It would be a project in South Africa, for the central eight blocks in Cape Town. We consider it the most interesting of our projects. Of course, our best projects are our two daughters, but we are now talking within the framework of Energoprojekt. Cape Town is best known for its diamonds, so we designed eight huge city blocks symbolically as diamonds. It was a very interesting project, but in the end it all depends on who you have as an investor.

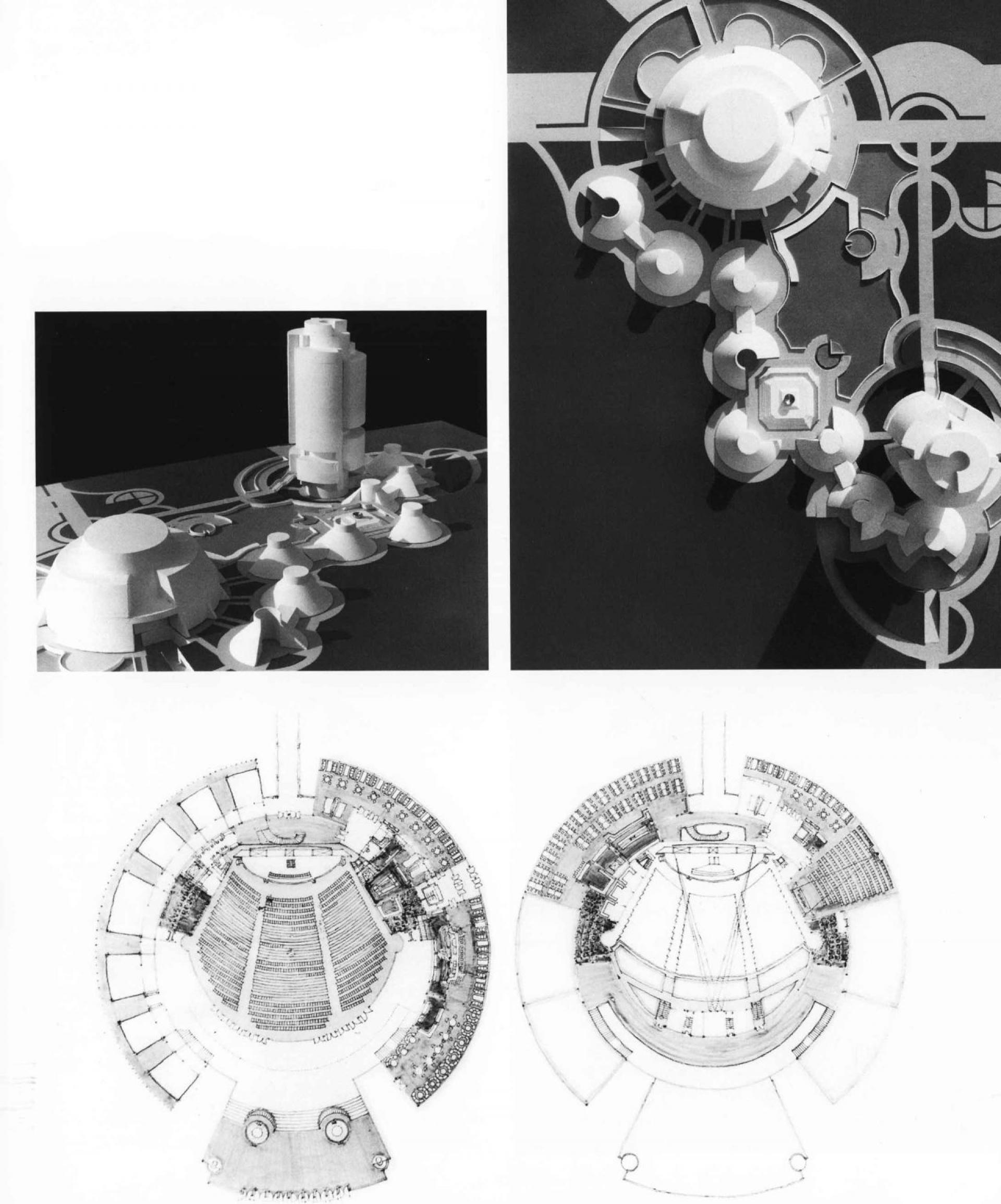

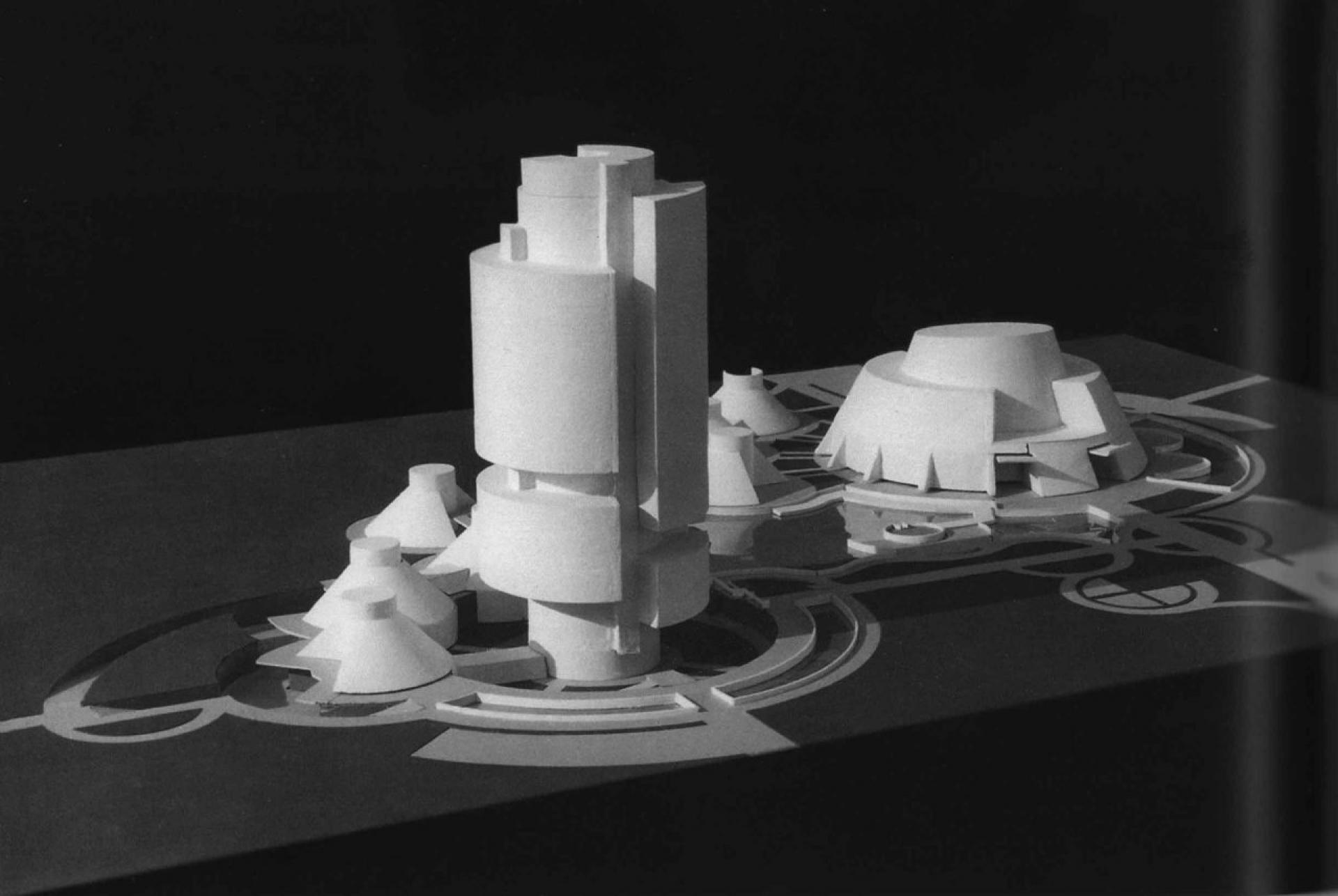

The model for the Cape Town project. | Courtesy of Dragoljub Bakić

It happened suddenly, a person from Cape Town appeared at Energoprojekt with a question: “I have a program, can you do a project?” The general director of Energoprojekt noticed his tattered sweater and repaired shoe, therefore he said that this guy might not be serious. I replied that we shall work on such an interesting program. It turned out that the director was right. Both project we created with Ljiljana were well accepted by the city administration and also presented via articles in the newspapers as a symbol of Cape Town, such as the Opera in Sydney.

Plans for the Cape Town project. | Courtesy of Dragoljub Bakić

However, in the early 1990s a change in power occurred in the South African Republic. It turned out that the person offering us work was a former mercenary who was killing black people. The project was stopped. However, I had hope that with Cape Town’s local administration we could continue the project in a different way but in the meantime we moved with Ljiljana to Zimbabwe to run the Energoprojekt burro there.

Never constructed eight city blocks in Cape Town, The Republic of South Africa (1993). | Courtesy of Dragoljub Bakić

The former mercenary somehow found us in Zimbabwe as he found out that I have a connection with the main architect of the Cape Town municipality. He admitted to me that he killed people and that if I will make another trip to Cape Town for this project he would do the same to me. Ljiljana would not hear of us stopping to do it, she was so in love with this project, she accused me being a coward. In the end, we dropped that project and that left us with regret. Afterwards Cape Town started to develop as any other city. We consider this to be our biggest project that was not constructed.

ENERGOPROJEKT

You have spent your lifetime in Energoprojekt, in Belgrade and around the world. How did it all begin?

DB: Energoprojekt took college students. Professor Boža Petrović suggested to Energoprojekt to hire me and Ljiljana. The famous Milica Šterić immediately accepted me as a man, but she did not want to hire women architects at all. It was in 1963 and I was 24 years old. I got then into Energoprojekt and stayed there until my retirement. A few years later, when we were supposed to work on a competition for a spa in Igalo, I proposed to Milica that Ljiljana join us. When she saw how Ljiljana thinks and works, she made an exception and employed a female architect.

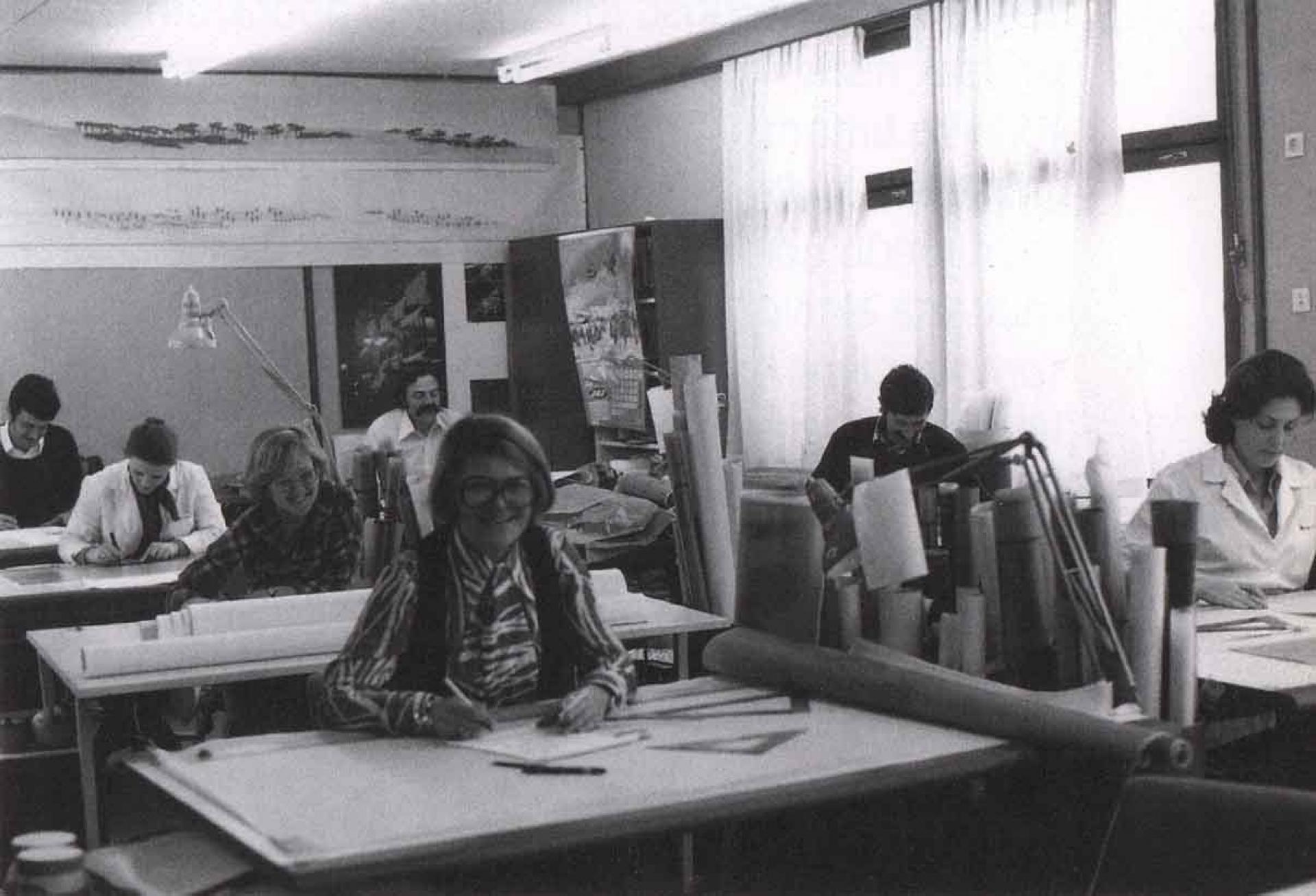

Ljiljana Bakić at TIM 10 architecture and urbanism Energoprojekt. | Courtesy of Dragoljub Bakić

Milica Šterić was extremely important for our architectural environment, as the director of Energoprojekt, as an architect, as an author. And she was progressive with her ideas. How come such attitude towards women?

DB: I don’t know why she only worked with men. She was a miracle of a woman, but something of that composition that was then in Energoprojekt irritated her, and she decided that she would no longer accept women. She changed her decision when she met Ljiljana, but she remained an exception. Though we had very many women technicians, who were very important to us in our work. We had top-notch technicians who you really only lead through the main idea, and they solve the rest. And back then, we drew every detail, gutters, and canopies.

Milica Šterić with her team at Energoprojekt. | Photo via Žene u arhitekturi

On the other hand, we can also say that Šterić played an enormous role in the development of our architectural profession, that is, the development of the author’s creativity and the quality that has arisen from it?

DB: Yes. At one point, Milica Šterić decided to withdraw from Energoprojekt, which was concerned more with energy, hydro power plants, dams, industries, heating plants, etc. When Milica formed a team with Zoran Bojović, Ljiljana and me in the early seventies, she decided to separate from Energoprojekt. We created a special design office, subdivided it into bureaus. Ljiljana and I were running a bureau of 7 in total, and we were called Atelier 5. Everyone had their own investors and salaries. We were particularly chasing business, acquiring investors, and it remained so till the end.

We are talking about the time of socialism, and you are talking about a market game and individuality. How’s that now?

DB: It was not customary for such a large social enterprise to individualize itself to that extent. Energoprojekt was special, it had 5,500 engineers and a workers’ council. Neither I nor Ljiljana were ever members of the party, and our whole life we did what we wanted, so nobody interfered with us. That is something that is not possible here today.

All this was largely due to Milica Šterić. The freedom that we had, the great confidence that she had in us young people. She developed herself by spending a good period of time working with Jaap Bakema in the Netherlands. In our country, she was the first to make a bearing glass facade, which is no longer present, and it was done with the most common ethermitte in the parapet. Very simple and cheap. She received the 7th of July Award for that house. She was an extraordinary personality, infinitely unselfish, in love with architecture at the cost of her private life. And also a great partisan. She kept our backs, of course, but the party did not meddle in what should be professional - unlike today.

Milica Šterić (1984). | Photo from the SAS catalogue “Nagrada arhitekture Srbije”

Yes, Milica played a big part. But there was also a system; our possibilities were unbelievable in relation to yours. We lived completely in a different time, with other conditions, opportunities, and career developments. What is happening today is horrible.

It is very interesting that thanks to Milica within a huge social enterprise we could sign as authors. It could not happen everywhere. Energoprojekt nurtured it; we struggled to be able to sign as authors. In smaller offices the directors were always the signatories of the projects. It was only in Energoprojekt that the architects themselves were signed as authors and this was a great achievement that we had won.

Your careers started in Kuwait and ended in Zimbabwe?

DB: We were very young when we went to Kuwait. With 25 years old this was a good period in our lives. This was the only time when Ljiljana and I work separately; me in Energoprojekt’s office and Ljiljana in the private office of construction engineers Sait Breik and Marwan Kalo. In order to get employed there she needed a special permit from Energoprojekt because it was a competition firm. At that time Yugoslavia was an exemplary ordered country. Especially in Kuwait, Ljiljana did a lot of projects because their office was then one of the busiest.

They begged us to stay there, but loyalty to Energoprojekt and our professor who employed us there were greater. We returned in 1966, and on that occasion we visited in detail almost all the Arab countries. In my opinion, study tours for architects have greater value than the study of architecture itself.

Headquarters of the Government of Zambia and the UNI Party1, Lusaka, Zambia, 1968-69. | Courtesy of Dragoljub Bakić

Our daughter Olga was born in 1967 and Biljana one year later. For Ljiljana and me our family was a sanctuary above everything else, therefore Ljiljana cut her career and spent the next four years devoting her attention to the education of our children. This proved to be very good because they have become more successful than their parents. We are proud of them as well as of our wonderful and serious sons in laws, Radovan and David. Our five grandchildren - Katarina (16), Julia (13), Jan Gabriel (12), Luk Daniel (10) and Klara Rose (8) are a real miracle. They live in New York and Warsaw, and they are growing so far away from us that with the years passing, it’s getting harder to meet them.

You were going back and forth, Yugoslavia, Middle East, Africa?

DB: We lived in Zimbabwe on two occasions in 1982/83 and in 1994/2001. During our first stay, we worked on the Congress Center with the Sheraton Hotel, which we received through an international competition. The project was published in detail in Anthony Krafft’s edition “The Contemporary Architecture of the World - 1987/88” in Lausanne, Switzerland.

Sheraton Harare Hotel is located next to the International Conference Centre in the capital city of Zimbabwe. | Courtesy of Dragoljub Bakić

During the second stay in Harare, we managed two Energoprojekt design offices Desicon and Bakić Architects. The second one was registered in our names because we had to get a RIBA license, but in practice we gave it to Energoprojekt. Bakić Architects has done and implemented dozens of projects mainly working for various ministries of the Government of Zimbabwe, and has received high recognition from the United Nations, which included it in its special list of 20 designer boutiques firms (up to 50 employees) around the world.

Headquarters of the Government of Zambia (model). | Courtesy of Dragoljub Bakić

Out of our 40 years of intense architectural practice, we worked more than 10 years abroad. We worked very hard as very often we brought our work home from the office and continued solving the architecture. We’ve been in such a way for nearly 60 years.

THE ANATOMY OF LIFE

You participated in many World Congresses of the International Architects Union - UIA, which has its headquarters in Paris. Which one do you particularly emphasize?

DB: Those encounters with numerous architects from all over the world meant a lot to us. UIA congresses became very popular and gathered thousands of architects. The ones in Madrid in 1975 and in Montreal in 1990 were special. Particularly important for us was the one held in Chicago in 1993, where Ljiljana had her report especially praised by the President of the UIA - Greek architect Vasilis Zgutas, as well as the one held in Barcelona in 1996, when our Olga had her report immediately after the completed master’s study at Cornell University in America.

Dragoljub and Ljiljana with their daughters Biljana and Olga. | Courtesy of Dragoljub Bakić

In Chicago, we officially represented our country’s delegation to the Congress, and it was only Ljiljana, because they did not allow me to enter the United States because of the international sanctions. However, I had a decent substitute, because our younger daughter Biljana accompanied her. She had already settled in America that year and started her trip towards a triple magistrate and graduation at Harvard.

In Barcelona, we were again official representatives as the delegation of Zimbabwe and as Vasilis Zgutas commented - that we are indestructible - we lose one country and we quickly find another one. Barcelona was and is now a soft spot for architects. It is one of the most successfully urbanized cities of the world, especially architecturally enriched after 1992 when the Olympic Games were held there.

What else did you do besides the architectural practice and design?

DB: Our profession has a lot of charms. It is welcome in many human activities in the field of culture, but also in real life as well. It directly affects the lives of people and makes them richer and more beautiful, and people are often are not aware of it. The greater the awareness about architecture itself, the more the business is respected in society. And vice versa.

Unfortunately in the last 30 years, all human values have been turned upside down here, and our profession, like many others, passes heavy days at the very margin of society. We remember something different and we are happy to remember that.

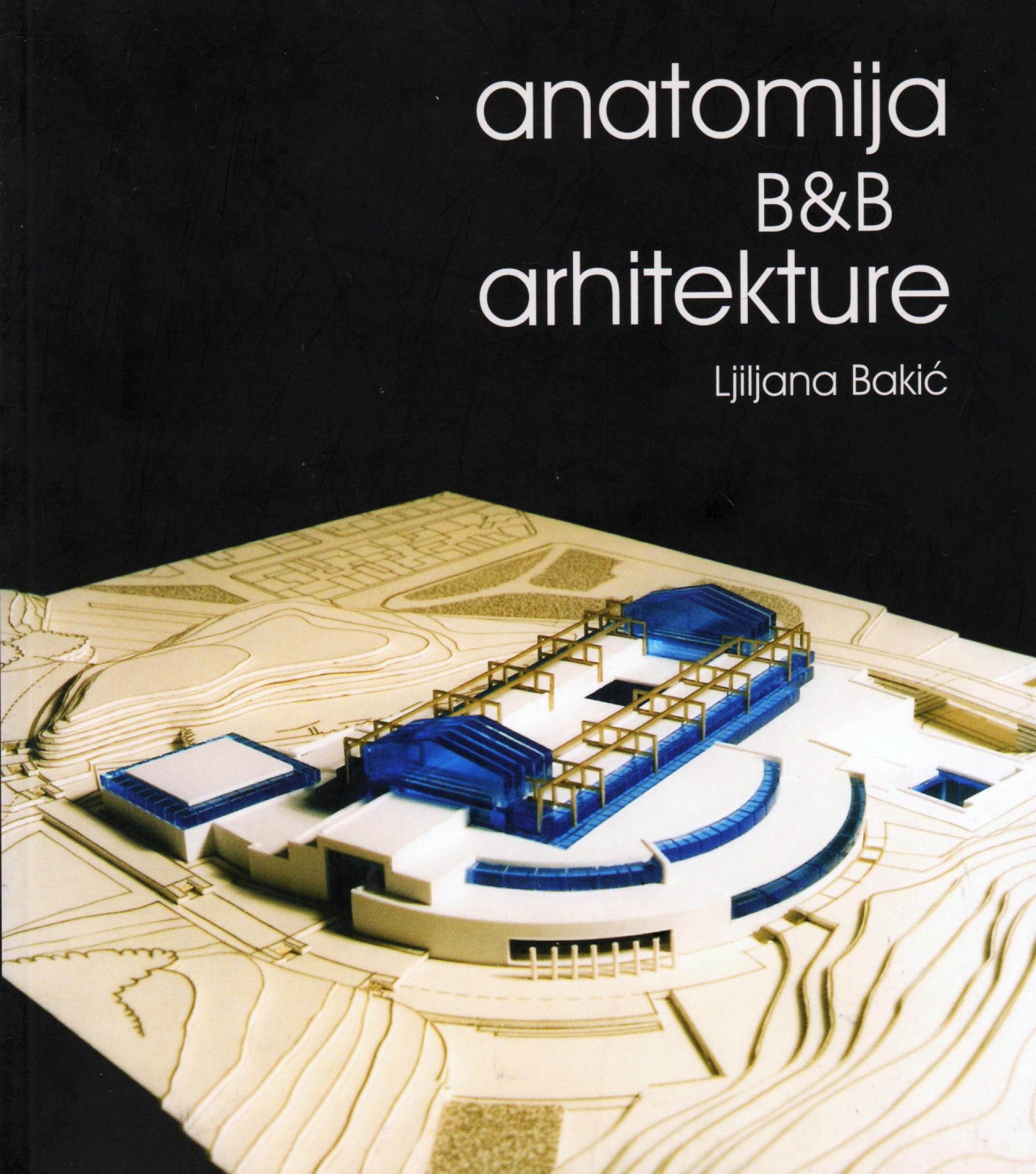

Ljiljana’s book “Anatomy of B & B Architecture” was awarded Ranko Radović Award (2012) in Serbia for the critical theoretical texts on architecture.

Ljiljana was the one who always wrote well, so she continued writing alongside her architectural practice, which is not often the case with architects. She seriously dealt with the philosophy of architecture, the theory of architecture and architectural criticism, and was very appreciated especially by the professional public. She has written dozens of texts, not just about architecture and urbanism, but also about the socio-political, sociological, and cultural environment in which we lived and worked. Many are represented in the book published in 2012 Anatomy of B & B Architecture.

Together we were also very active when it came to exhibitions of architecture and design. I was more active in the Association of the architects of Yugoslavia and Serbia, where I was the president of the Court of Honor for 20 years. We were very much concerned with the profession and it would happen that we deny membership in our Association to those who break the Moral Code of our architectural practice.

What the city administrations has in the meantime made of Belgrade, especially with the wild construction and investor urbanism, it would be difficult to qualify it today even for some Rural Sports Games.

You have received a lot of professional acknowledgments and rewards during your working life. Which ones are especially important for you?

DB: What I consider to be the biggest prize is the acknowledgment Ljiljana received in 2016, when selected to be among the 100 best and most important architects and designers of Europe for the period from 1918 to 2018. The MoMoWo- Modern Movement Women project is dedicated to the accomplishments of architects and designers throughout Europe and the year 1973 was dedicated to Ljiljana for the project of the Pionir Sports Hall.

What are you doing today?

DB: Both Ljiljana and I have entered our 80th year of life. Ljiljana continues to extensively write, this time her second book based on extensive journals that she diligently led during all of our turbulent and transitional years. We, who were born in the Kingdom of Yugoslavia, have changed five countries. From a large, populous and coastal country we learned to love, we now have a small continental one that continues to dwindle with both territory and population and for which we still do not know the boundaries and which we still cannot manage to make it resemble a real and normal state.

Again, according to the principle I have been holding on to for a long time - Carpe diem - I am trying to make, in a creative way, various things and entertainment in our yard for the short time during the summer when our grandchildren visit us. I work a lot in the garden, which I find inspiring and on a hill, from which the view of the Danube is beautiful. We are only five kilometers from the city center and yet we live in complete nature with a multitude of birds and animals.

Ljiljana and Dragoljub Bakič at the MoMoWo exhibition in Belgrade (2018). | Photo by Rade Kovač

As Ljiljana continues to deal only with her writing, I had to take over the kitchen and in the everyday cooking I discover great creative possibilities and in time it has also become a hobby.

You are still very strong and active in the public sphere, and persistent in fighting for the future of Belgrade, and not only in terms of architecture.

DB: I am engaged with a bit of professional and civic activism, because I think that citizens should not hide their heads in the sand, but if they are educated then it is their duty to express their views when needed. I am trying to give my contribution to the fight against the uncaring and the unqualified city government that demonstrates its power by deploying real Urbicid in the systematic and daily destruction of the country’s Capitol. Unfortunately, they are successful because our profession, preoccupied by bare survival, absolutely provides no resistance.

Do you think that there is something that should be explicitly explained which might then be the conclusion for this story?

DB: It bothers me that as the prevailing impression remains that thousands of flowers flourished in all those past times. And that was not the case at all. This, our very own Orwell, which we experienced in 1984, was made by powerful local politicians within one of the only existing political parties, to hide and draw away public attention from the just discovered malpractices’ of private purchases of apartments in downtown. In this, they were ardently supported by a group of our colleagues from Energoprojekt, a group of unappreciated architects, who were blinded by great envy. They could not forgive me and Ljiljana for the huge success we achieved with the project of the Congress Center in Zimbabwe and the very fact that we personally brought this business to Energoprojekt.

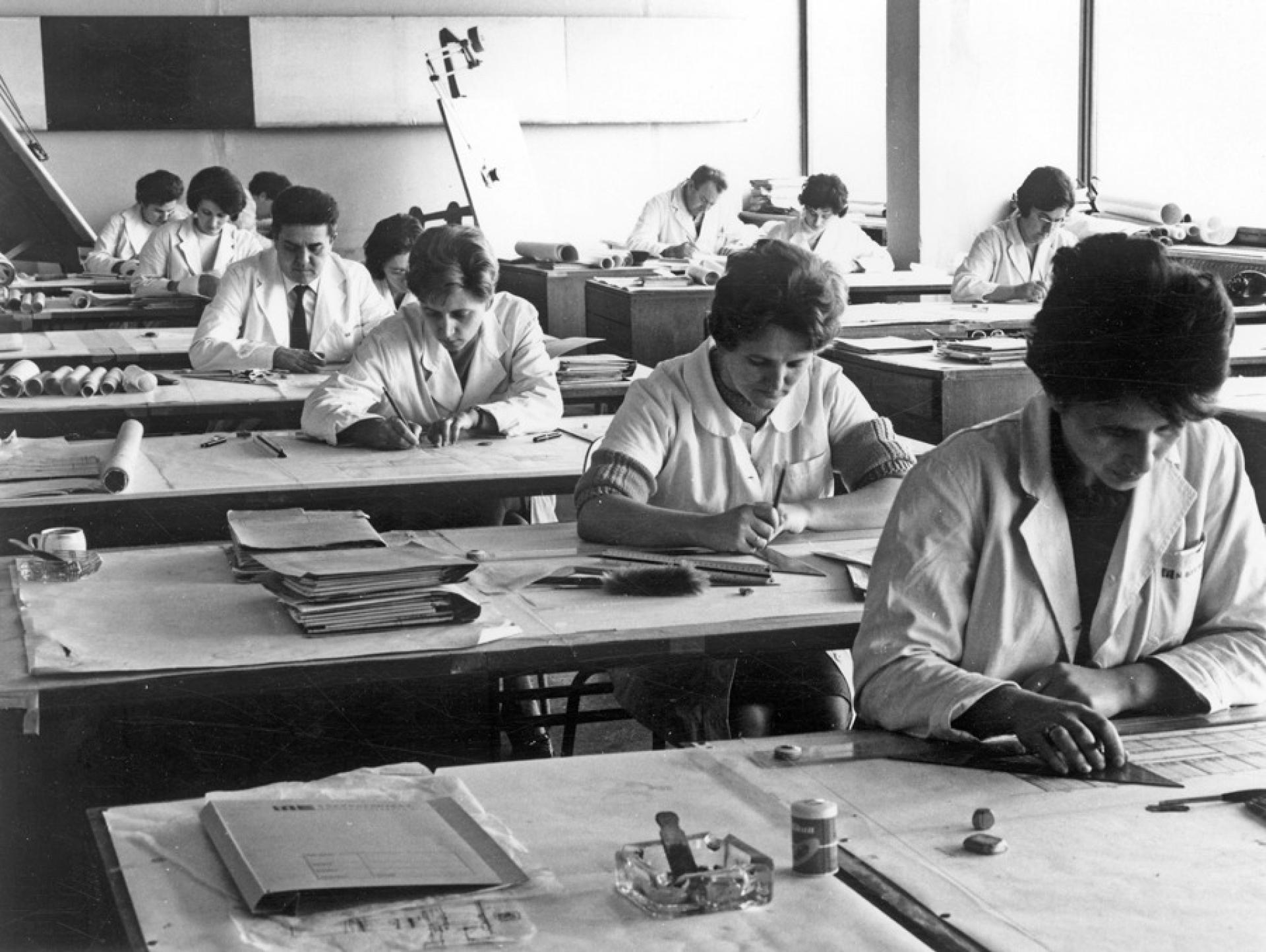

Male and female architects at work in the Department of Architecture and Urbanism at the headquarters of a major construction firm Energoprojekt in Belgrade. | Photo Courtesy Energoprojekt Archive

The whole world was opening for us. Suddenly, we stood out. We had to be cut. And that’s what happened. We were stopped in our 45th years of life, at the very peak of our careers when we were able to give the most.

All this happened in the second half of the 1980s, in the era of social ownership and the rule of a political party. Today there is private property, bared liberal capitalism and again the rule of one political party. Everything could be reasoned with if there were real institutions and the rule of law. In our 80 years of life, we have not managed to experience this wonder which is called the Rule of Law.

In those 80 years a lot has changed, but even with Yugoslavia – we cannot speak of it as a uniform entity, neither in time nor in space.

DB: Of course, in the era of socialism there were great differences, compare let’s say Serbia and Slovenia. For example, we could not even dream of having private offices, nor did any architect dream of having a private house. It would be normal for you as an architect to first try your experience on your own home - why not buy it and do it. I would say that as a condition: first you have to make a project for your house, and then for others. This was massive in Slovenia, for us, all that time they were the complete West. Slovenian architects really started with their homes, there was no architect there who did not designed his own house.

But then, in the end, you live in the house you have designed!

DB: Of course, that was one of our tricks.

Dragoljub Bakić at his home. | Courtesy of Dragoljub Bakić

—

With Dragoljub Bakić were talking Ljubica Slavković and Iva Čukić