From Plečnik To Corb

What did Jože Plečnik, the architect of modern Ljubljana with a critical view on Modernism and Le Corbusier agree on? An exhhibiton at the Museum of Architecture and Design (MAO) is deliberating the question: Plečnik’s students and other Yugoslav architects in Le Corbusier’s atelier is curated by Bogo Zupančič. And here is a hint, the answer lies in Plečnik’s teaching.

Le Corbusier’s atelier in Paris. | Source © MAO Collection

Miroslav Oražem, Milan Sever, Hrvoje Brnčić, Marjan Tepina, Jovan Krunić, Edvard Ravnikar and Marko Župančič were seven of Plečnik’s students who worked at the atelier of Le Corbusier and Pierre Jeanneret in 35 Rue de Sevrès in Paris. During the pre-war period students from Slovenia flocked to Corbusier’s atelier. They were almost as numerous as architects from France, Switzerland and the USA. Other architects from Yugoslavia who worked for Corb included Zvonimir Kavurić, Ernest Weissmann, Juraj Neidhardt, Ksenija Grisogono and Krsto Filipović from Croatia and Milorad Pantović and Branko Petričić from Serbia. The Croatian architects were the first to join Le Corbusier’s studio in 1927.

Marjan Tepina and Le Corbusier in the Paris atelier (1939). | Source © MAO Collection

In Ljubljana’s Faculty of Architecture in the 1920s students expected their professor Jože Plečnik to teach them contemporary trends . It was after all the period of Functionalism, Bauhaus and the CIAM congresses, but they were wrong. Despite the fact that Plečnik was seen as a pioneer of Modernism, due to his early projects in Vienna and Prague, the Church of the Holy Spirit and Zacherl House, he rejected functionalist architecture, deeming it too rational and cold. After a visit to the Acropolis in Athens (1927) he began to pass on his views of classical elements and principles in architecture to his students. “What Corbusier knows I know as well, but what I know Corbusier doesn’t!”, he is famously quoted. He rejected the industrialisation of construction and was more at ease with the crafts and traditional materials. To his students he introduced solutions with practical outcomes through hard work. This might be a reason why up to 15 % of Plečnik’s students left and went to work for Le Corbusier. They had the desire to step away from Plečnik’s traditional views, unable to satisfy their curiosity for what they deemed to be more contemporary currents in architecture.

Milan Sever (first from left) and Junzo Sakakura (in the middle with glasses) at the Paris party in 1933/34. | Source from private archive

This interest started to grow in 1925 when Plečnik’s students visited the International Exhibition of Modern Decorative and Industrial Arts held in Paris . Le Corbusier’s Pavillion L'Esprit Nouveau encouraged them to start enquiring soon after graduating about scholarships offered by the French government and travel to Paris. All scholarship recommendation letters were written by Plečnik, demonstrating his openness and broadness. Already in the autumn of 1925, Dušan Grabrijan had left for Paris. He did however not got to Le Corbusier’s studio but attended the advanced study courses offered by the École des Beaux-Arts. The first Slovene in Le Corbusier’s atelier was Miroslav Oražem who arrived in April 1929 and stayed there during the academic year 1930/31.

Marjan Mušič, France Ivanšek (ed.), Anthology of the Department of Architecture of Ljubljana University 1946-1947. | Published by DZS Ljubljana, 1948

The friendship between Dušan Grabrijan and Juraj Neidhardt, who collaborated with Le Corbusier on his most resonant projects from 1933 to 1935, made it possible for Milan Sever to join the studio in 1933/34 thanks to Neidhardt’s intervention. The good impression made by the work of Plečnik’s first two students in the studio acted like an admission pass for the other Slovenes. A three-year break was followed by a Slovenian "invasion” of the atelier, or the beginning of L'epoque Slovène as Le Corbusier himself called it. From the end of 1937 to June 1939 Tavčar, Bleiweis, Novak, Brnčić, Tepina, Krunić and Ravnikar worked with Corb. With the war underway in December 1939, Jovan Krunić and Marko Župančič joined the studio to draw up plans for military facilities following the system of Jean Prouvé. At the same time three of Plečnik’s students who had already worked with Le Corbusier, Sever, Tepina and Ravnikar, attracted attention with their works presented at urban planning and architectural design competitions. Two held in 1940 are worth mentioning, the architectural competition for a residential care home for the elderly at Bokalce, where Tepina was awarded the first prize, and the competition for developing and regulating the Medlog settlement near Celje, in which Ravnikar was the winner and Tepina was second. As a result of the competition for the regulation plan of Ljubljana in 1941 the projects by the three above mentioned architects were taken on.

Poster “Architecture in FPR Yugoslavia” by Branka Tancig from E. Ravnikar seminar (1951), letterpress printing, Ljudska pravica Ljubljana, 510 mm x 380 mm. | Source from private archive

After the end of the second World War times of reconstruction on the basis of modernist concept prevailed. Le Corbusier’s ideas played an important role in modernizing the society. Plečnik’s and other Yugoslav students who had worked with Le Corbusier were appointed to important posts in the administration, state offices and at the universities. Their committed professional, pedagogical and public activity marked the late 1940s and 1950s.

After Edvard Ravnikar took up his position at the Department of Architecture of the Technical Faculty of the University of Ljubljana, thereby becoming one of the key figures in architecture also across all of Yugoslavia, Plečnik took the back stage and sank into oblivion. Modernism or the International Style became the dominant style. Ravnikar and his collaborators conceived several architectural projects from renovations of villages to designs of new cities like Nova Gorica and Novi Beograd, from residential to prestigious public buildings with traces of Le Corbusier’s influence to be found in all of them. The list of works is extensive, yet many valuable designs have been lost.

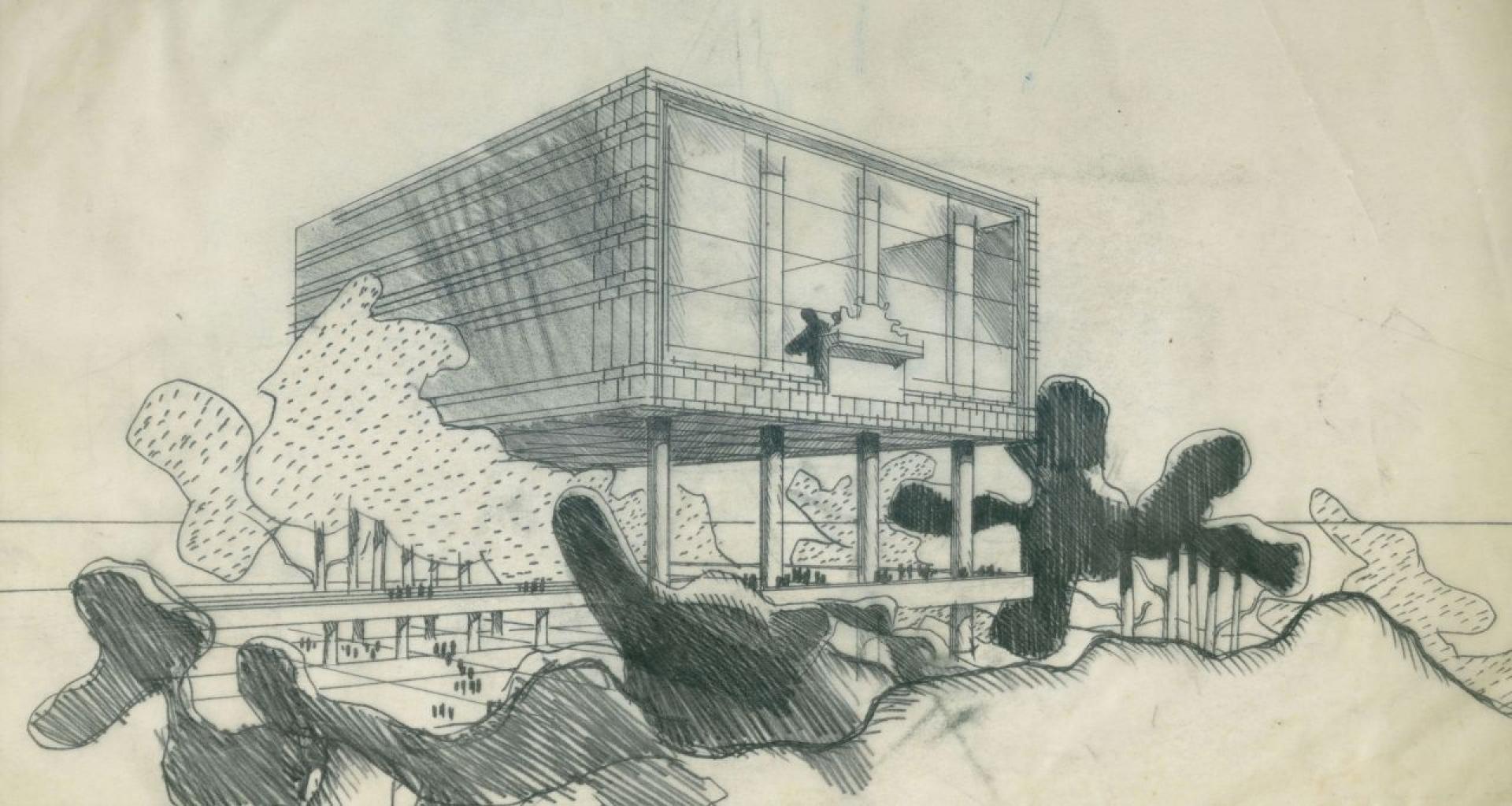

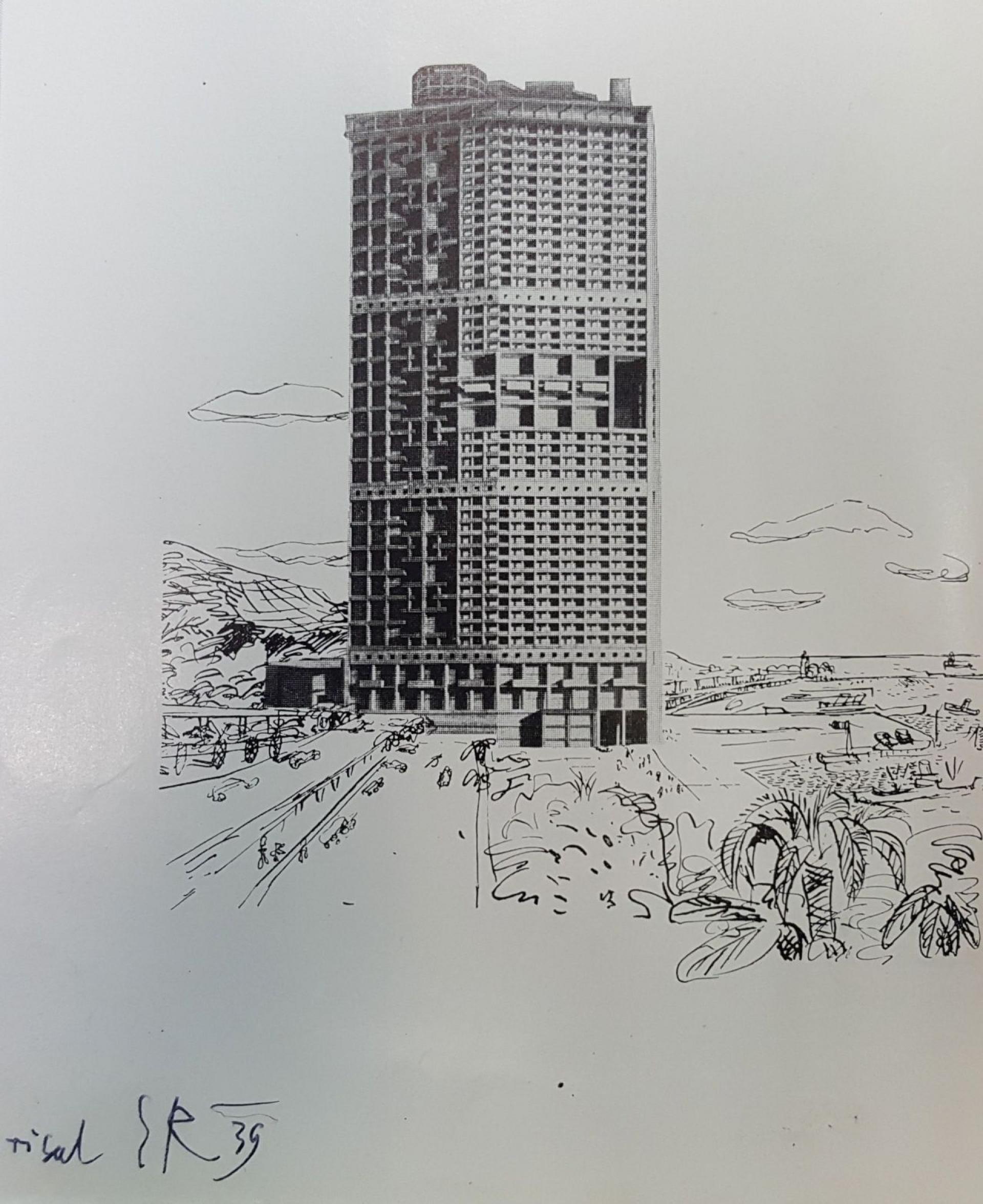

Copy of drawing in perspective of a representative building, no signature, no date, 240 mm x 310 mm by Edvard Ravnikar. | Source © MAO Collection

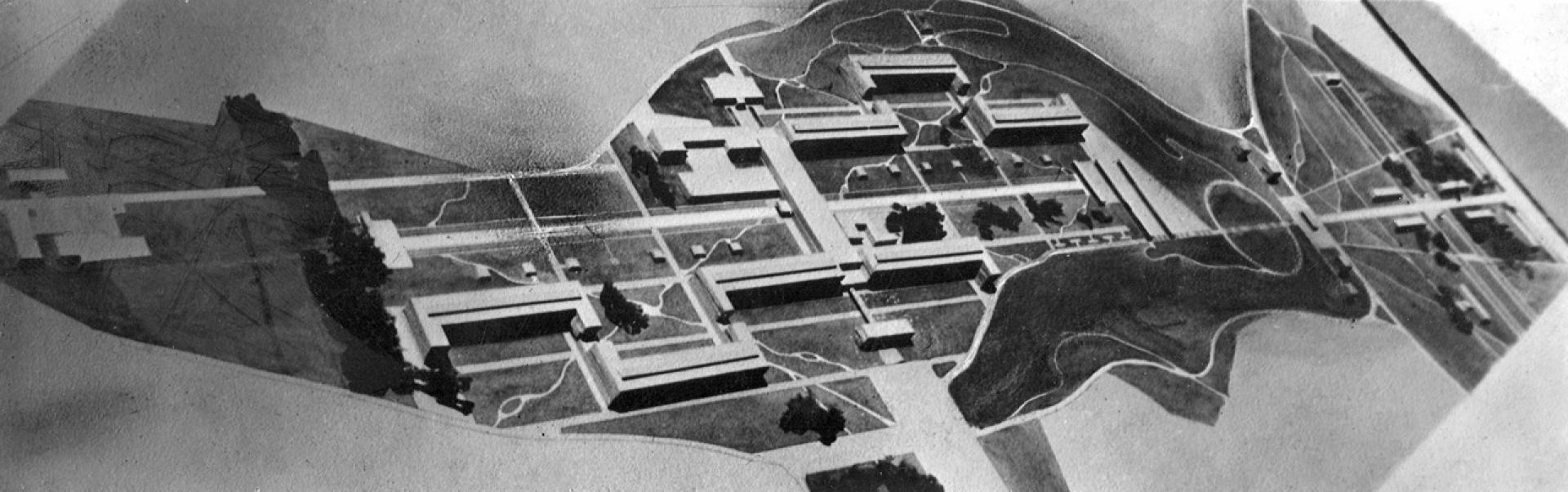

Model for the architectural competition for a residential care home for the elderly at Bokalce in Ljubljana by Edvard Ravnikar (1941). | Source © MAO Collection

Although Plečnik’s students were enticed by Le Corbusier’s ideas as early as the 1920s, they became with the time more critical of them and had, by the mid-1950s, turned away from them. Slovenian architects did not blindly replicate the examples found in Le Corbusier’s atelier, they thoughtfully and independently interpreted them, which is why Le Corbusier’s influence is often concealed and also undefinable. Thus, as an example, Ravnikar’s refined works are known for their hefty constructions which no doubt demonstrate Le Corbusier’s influence, yet the facades are designed in his very own way within the historical and spatial context. This is how these former Plečnik students differed from numerous other Slovenian and Yugoslav architects who grew old with the ideas of Modernism. The Slovenian architects’ connections with their peers such as, for example, Ernest Weissmann, Juraj Neidhardt, Gyorgy Kepes, Charlotte Perriand, Willy Valeke, Alfred Roth, Josep Lluis Sert, Kunio Maekawa, Junzo Sakakura, Max Bill, Ejnar Borg, Tage Nielson, Jean Prouvé and others whom they had (in)directly met in Le Corbusier’s atelier, were however valuable when it came to developing their careers and widening their horizons.

Edvard Ravnikar and Le Corbusier, copy of drawing of Algiers skyscraper with a note: "drawn by ER 39”, from the book Le Corbusier Oeuvre complete 1938-1946. | Source CTK (Central Technical Library), Ljubljana

The value of Plečnik’s works and his approach to architecture was again reassessed in the international professional arena with the decline of the International Style and the start of Postmodernism towards the end of the 1970s. The exhibition at the Georges Pompidou Centre in Paris in 1986 holds a significant merit for this development. The interest in Ravnikar and other representatives of his generation was not as strong as the interest shown in Plečnik, but today the interest in Ravnikar and his peers is resurging.

Although the positions taken for or against Modernism have marked the architectural debate for quite some time, the force and energy of Plecnik’s teaching approach led to the recognition of his pupils’ works by Le Corbusier who highly valued their craftmanship. Eventually this became a contributing factor when the lines started to blur.

Exhibition in Museum of Architceture and Design (MAO). | Photo © Bogo Zupančič

—

Dr. Bogo Zupančič is the curator for the architecture at the Museum of Architecture and Design (MAO) in Ljubljana and author of seven books on the history of Slovenian architecture Nebotičnik - the skyscraper of Ljubljana : Money and Architecture, Architect Josip Costaperaria and Ljubljana’s bourgeoisie, Chamber of Engineers of Ljubljana 1919-44 and a collection of four books The Stories of Ljubljana Buildings and People. In 2006 he received Plečnik’s Medal for his publicist opus. He is co-author of the exhibition of The Neighborhood And The Streets, which was opened in the MAO in memory of the times when the residential neighborhoods were built with the thought of their users.