The Introverted Seismograph

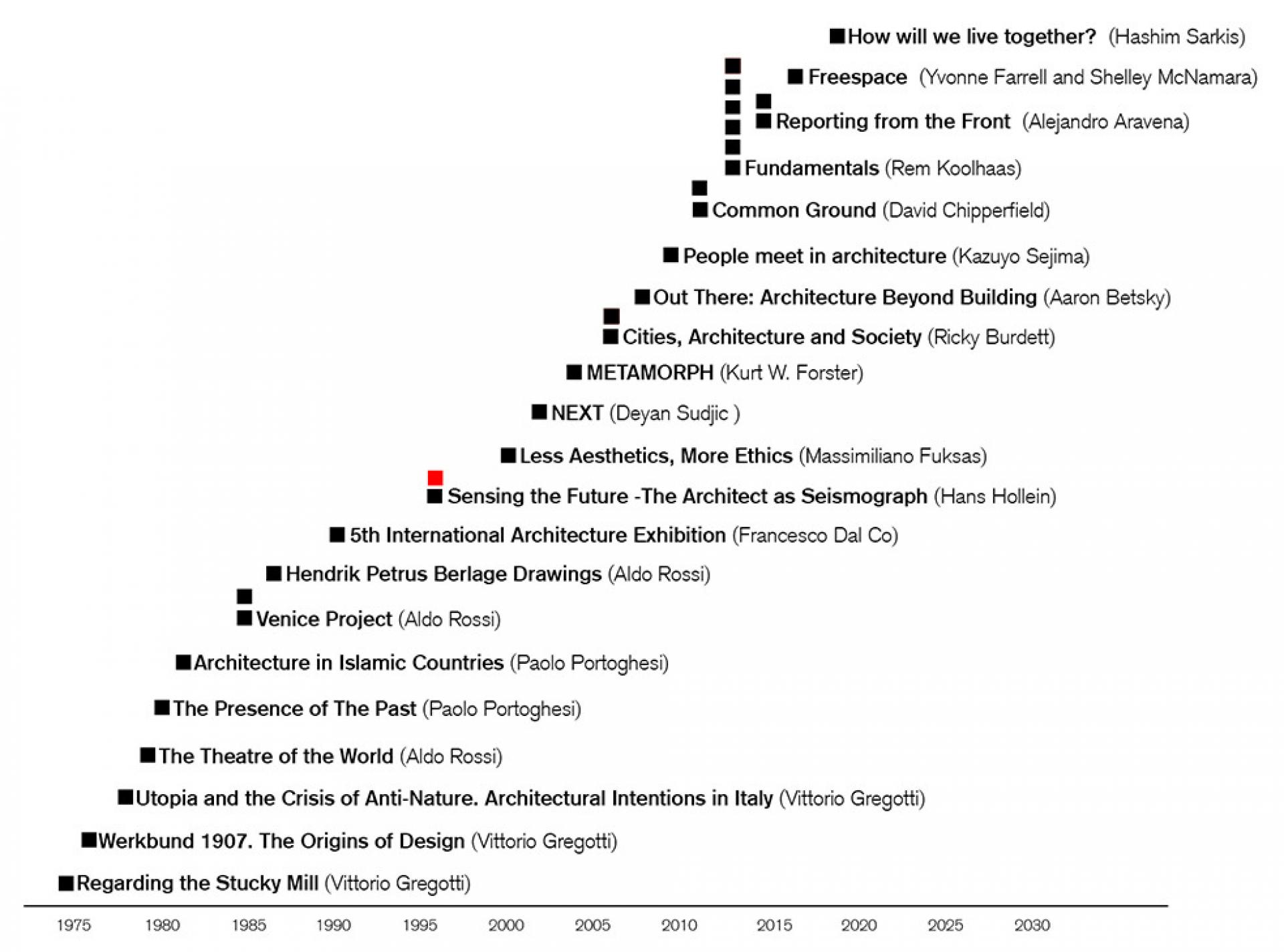

How can an architect sense underground vibes of the present time and translate them into the future? This was the question that Hans Hollein posed at the 6th Architecture Biennale in Venice in 1996: "Sensori del futuro". "L’architetto come sismografo" [Sensing the Future - The Architect as Seismograph]. The title contained a faint echo of Porthoghesi’s Biennale "The Presence of the Past", dealing between past and future memories, laying the ground for the Next Biennale in 2002. Hollein was the first non-Italian curator following the Unnamed Biennale in 1991 when Dal Co invited foreign countries, introducing national pavilions and opened the prestigious Arsenale with an exhibition of 43 architectural schools from all over the world.

Kyriakos Krokos | Photo © S. Staveris

Hollein portrayed several international star architects-including himself-via their hands, comparing them to a super powerful apparatus that can make predictions. Most of them are sketching, others are playing the piano, working at the computer or just explaining something. Some of them are dealing with the memories of utopias like Arata Isozaki, Massimo Scolari and Peter Cook whose captivating drawings revived past memories from previous Biennales. And some others are dealing with their own personal memories, looking into their past experiences, recalling colours, textures and materials and managing to display all these fragments of memory in such a way that when they are seen together, through analogies, they can convey deeper meanings and create dialogues. Kyriakos Krokos was one of them.

Greek pavilion at Venice Biennale in 1996: Kyriakos Krokos, curator Andreas Giacumatos | Photo © A. Giakoumakatos

Among all these powerful seismographs Kyriakos Krokos (1941-1998) made his appearance through his work in the Greek pavilion. An architect who dealt with his memories with the same passion and even more dedication than Pikionis (one of the few Greek architects who received international recognition and his work was showcased in the first Greek pavilion in 1991).

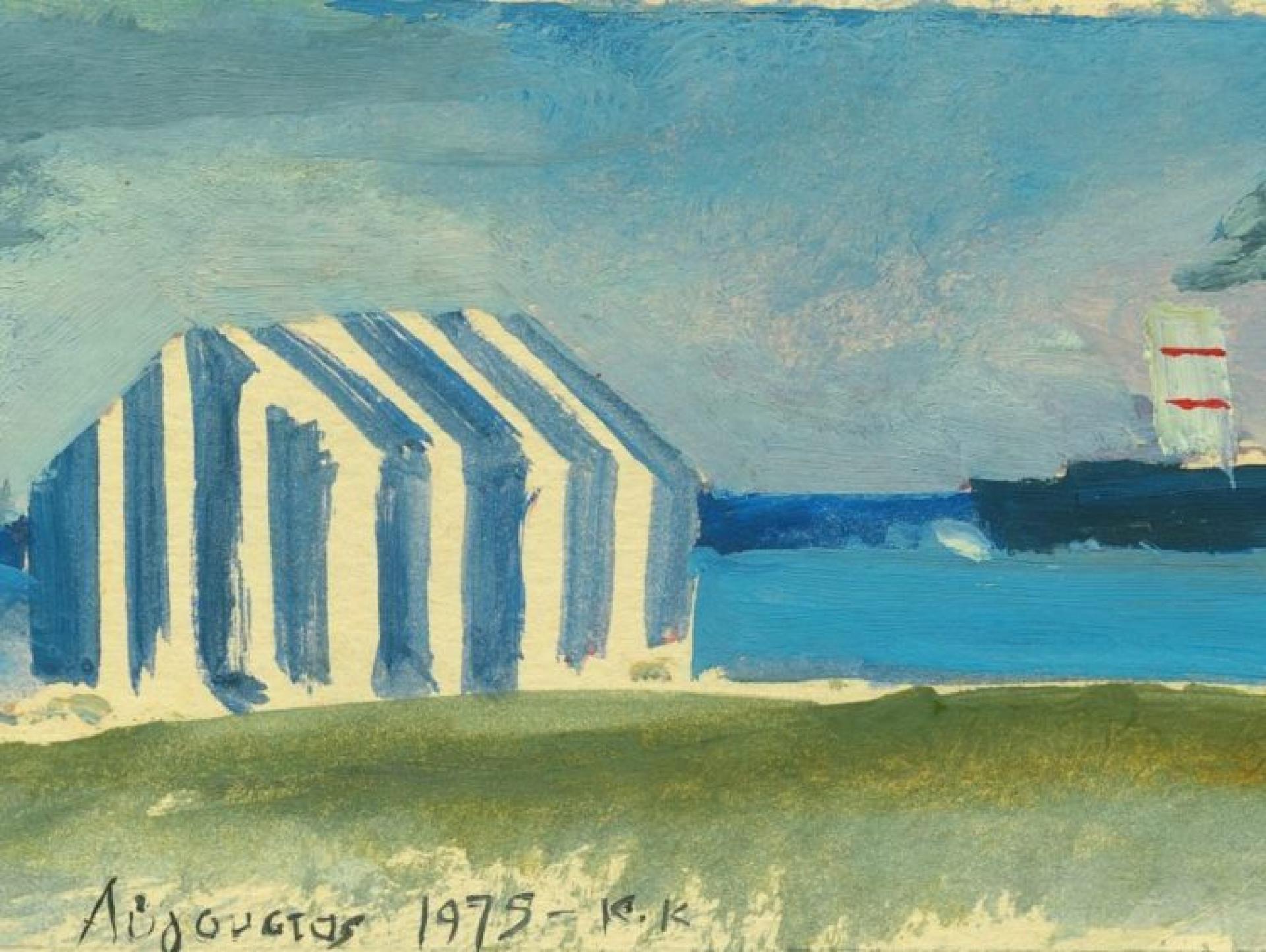

August of 1975 | Drawing © K. Krokos

“I wanted to get closer to my childhood senses. (…) Memory for me was a tool of liberation from the bonds the architecture school created” said Krokos and maybe that’s why he never wanted to be part of the architecture academic community. Back in the 1960s, he was struggling with the modern fashion as he referred to his studies at National Technical University of Athens where the influence of the modern movement is still present. How current remains this discussion even today when architecture schools create limitations and produce architects with restrictions following contemporary movements or star-architect clones. For Krokos, the only way for someone to be free of these bonds is to look inside oneself and try to see the world with the eyes of a child “..when everything was enchanting us (…) I felt the art as a substitute for innocence, that everything was trying to drown, and the great works to show the way back”.

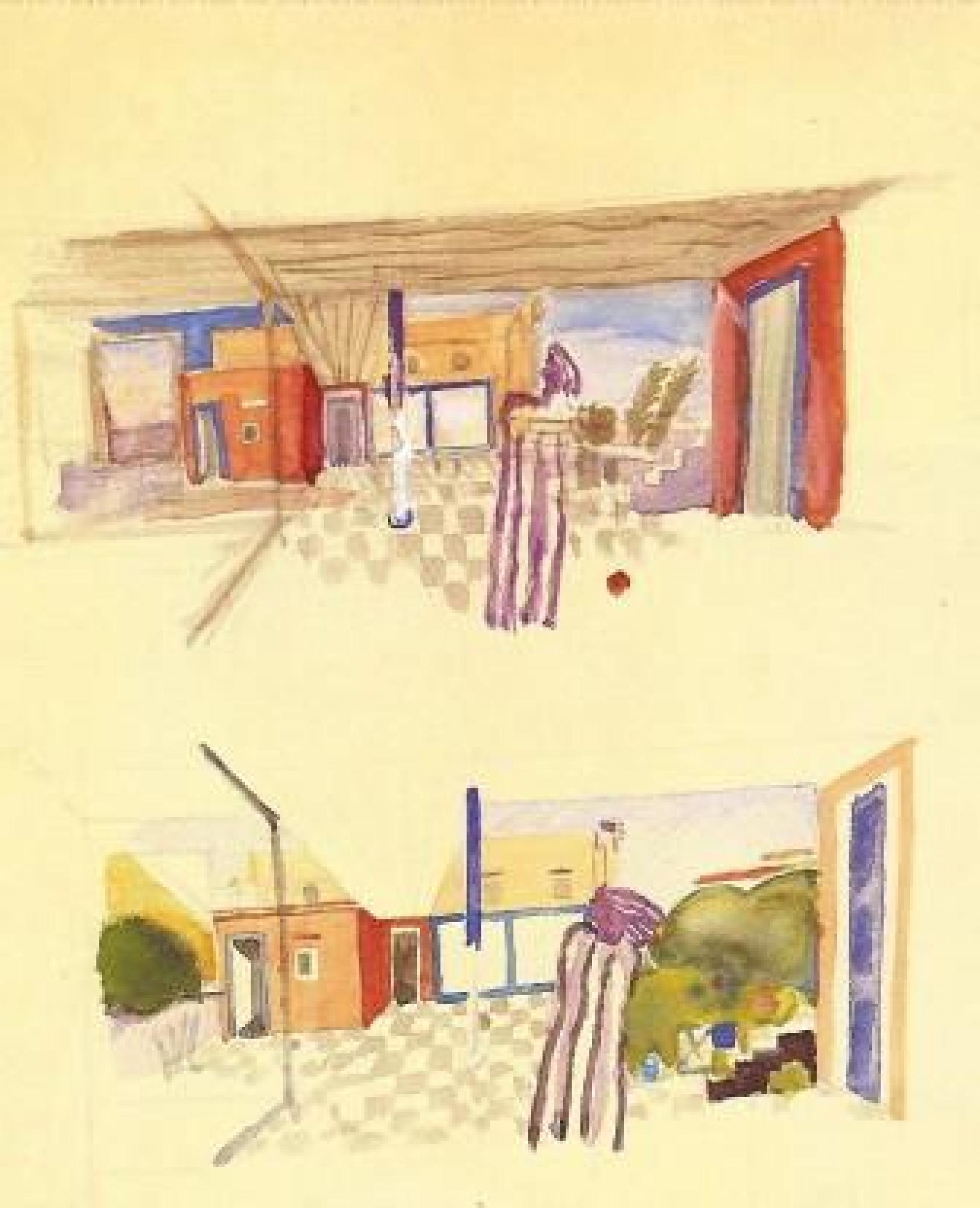

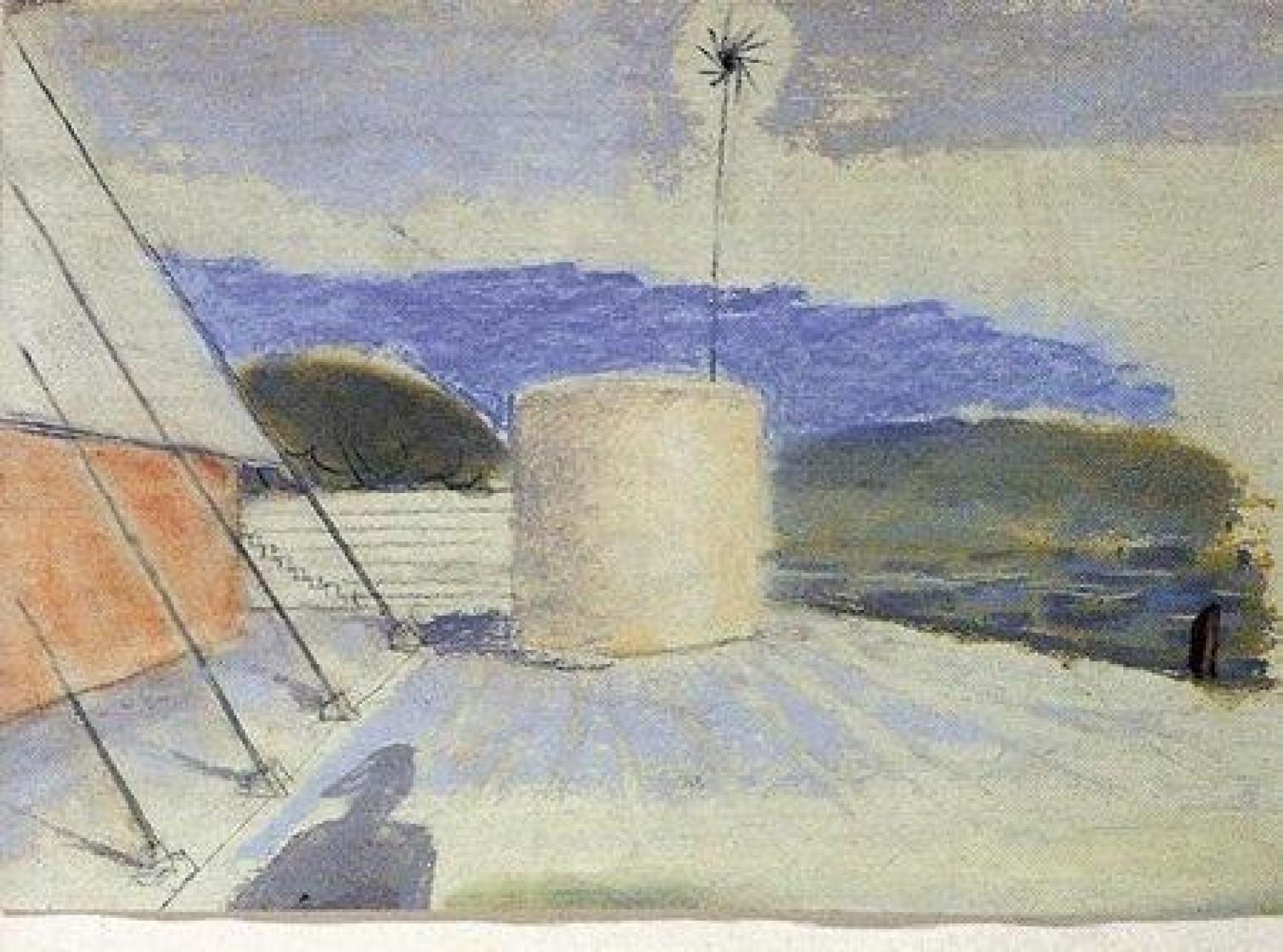

Krokos’ drawings © K. Krokos

He stood away from the avant grade of his era, showcasing in Venice Biennale local construction materials and fragments of his memories growing up in the agrarian island of Samos. Thus he managed to recall not only his own personal experiences and his path of becoming an architect but also pieces of collective memories from the people who lived and worked in the same region.

Museum of Byzantine Culture Thessaloniki | Photo © A. Giakoumakatos

For Krokos, architecture exists in time before and after its completion and he sought to attribute an active role of participation of every agent related to the construction. This practice implies an ethos, an attitude of life; to live according to who you are, to think and build as you live. Krokos saw the architect as craftsman, being actively engaged in the construction, introducing participatory methods, formulating a collective vocabulary, (thus very specific for each project) combing memories, materials, local techniques, colors, light and shadow in a section. “There are no right materials, there is the right relationship of materials” said in one of his few interviews, talking about principles which relate to bioclimatic factors, about sustainability and passive building systems. “The beginnings of the new fashion with concrete as the dominant material - this is not to blame, of course - confused us. The engineer now had to say how the house would be done. People no longer say I will build but I will pour a slab.” The 6th Venice Biennale was for Krokos his last work, redefining the question of making architecture, characterised by humanistic power with respect to both living bodies and the environment.

Fasianos house/museum by Krokos | Photo © A. Giakoumakatos

Is Krokos relevant today? Maybe his architecture wasn’t contemporary in his era either. His projects stand timeless, allowing us to look back when we feel the need. To look our own experiences, memories and traces of our bodies. To understand the environment we inhabit and coexist, comprehend our inter-connections, try to find associations between diverse places and the particularities of physical and non-physical elements. In an era that the architect as an autonomous persona has ceased long ago, maybe it is interesting to look into architecture through collective memories, as negotiation between rural and urban, individual and collective, text and context, political and planned, local tradition and digital technologies, moving away from fixed dichotomies.

Carl Jung in one of his letters to Freud explain the concept of analogy and analogical thought: Logical thought is what expressed in words directed to the outside world in the form of discourse. While, Analogical thought is sensed yet unreal, imagined yet silent; it is not a discourse but rather a meditation on themes of the past, an interior monologue.

The medium of analogical thought is memory, where the medium of logical thought is the language.

Christina Serifi is an architect, researcher and urbanist, co-founder of TiriLab (Future Architecture Platform Fellow) an initiative which explores multi cultural heritage related to techniques, technologies and culture specifics from communities in northern Greece. Christina is associate researcher in Terreform, where she has coordinated various publications regrading indigenous knowledge, alternative educational models and self sufficiency. Her work investigates forms, collective memories, typologies and local practices, focusing on urban fragments, in-between spaces, as well as osculation of architectural and social space, Christina has been awarded with the Fulbright fellowship and Urban Design Award ’14 from CCNY. | Photo © Norman Posselt