Trieste

In his Letters to a Young Poet Rainer Maria Rilke wrote: “Have patience with everything that remains unsolved in your heart. Live in the question.” Rilke wrote ten Duino Elegies at the Castle of Duino, which lies in a small north Italian village with the same name. The position between Karst and Adriatic sea makes the dialectics work in all senses. As Rilke said: “Let everything happen to you. Beauty and terror. Just keep going. No feeling is final.”

View at the Castle of Duino from Rilke’s trail. | Photo via Flickr

There is a Rilke’s path, which connects Duino with Sistiana. This picturesque trail along the seaside provide a scenic view of the whole gulf of Trieste. The city of Trieste lies on the Karst region, where contrasts defines the landscape and the dwellers. Landscape of stone, underground caves beneath, the two worlds marks the identity of the region. A strong wind Bora (Burja slov, Bora Ital.) with the speed up to 160 km/h is just another condition which defines how architecture of villages and cities was built. Because of these natural conditions people of the region claim to be stubborn and strong, almost solitaire. The story of Trieste as well presents some architectural solitaires, which marks the important periods of the city’s history.

The Temple of Monte Grisa stands at the edge of Karst plateau. | Photo via Panoramio

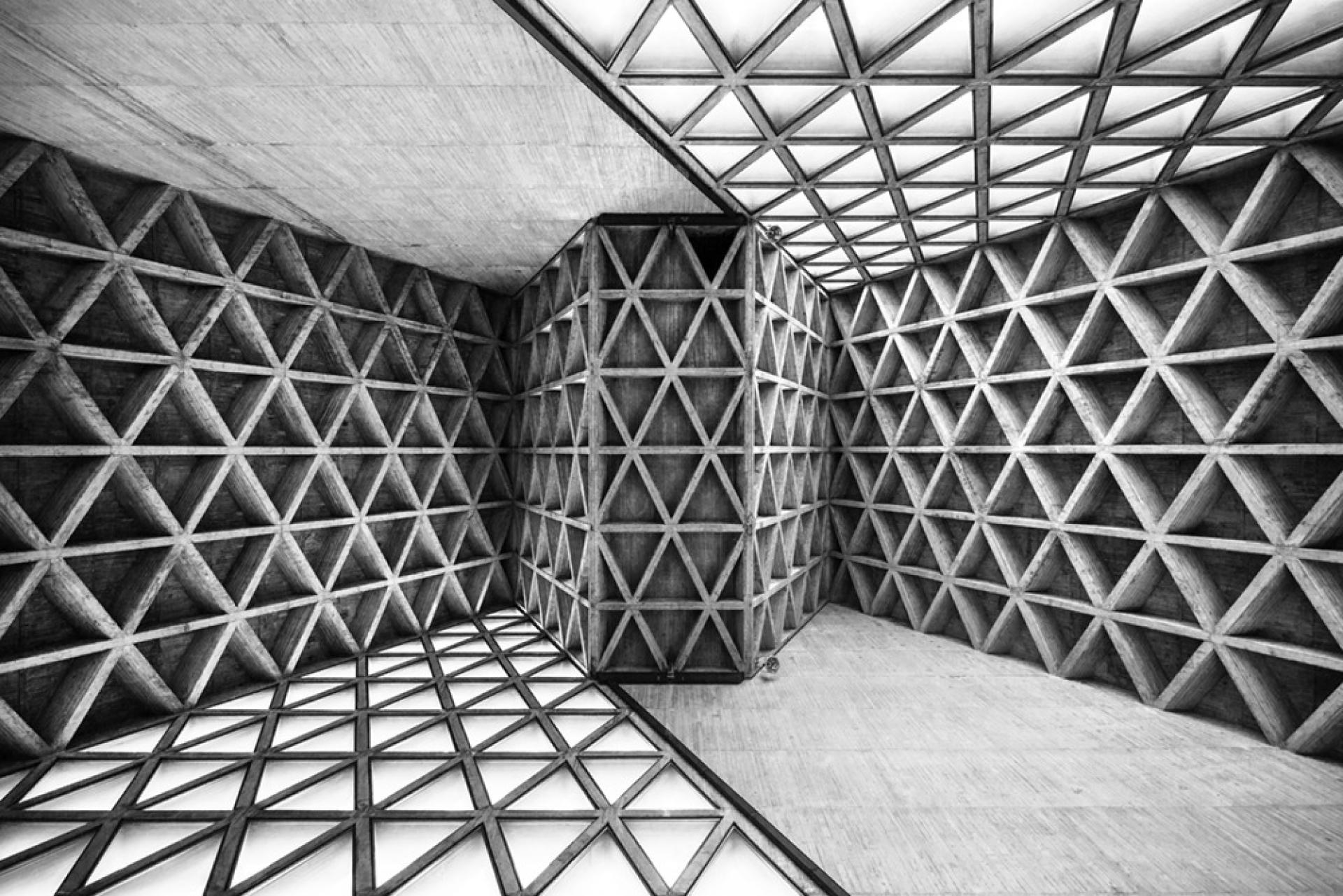

From the majestic view over Trieste, on the highest point of the plateau, stands an unusual architecture landmark, the Temple of Monte Grisa. An architectural solitaire that overlooks both the former Austro-Hungarian neo-Classical port and the Adriatic Sea. The triangular temple was designed in the 1960s by Antonio Guacci. Concrete brutal structure in its architecture composition evokes the letter M, symbol for Mary. In the landscape seems this architecture more an industrial object than a temple.

Concrete M structure of the interior of the Temple of Monte Grisa. | Photo by Roberto Conte

In the next scene we stand directly in the city centre of Trieste. There we encounter and experience the two identities, a Neoclassical Austro - Hungarian and the Rationalistic Italian. In between this two poles evokes some architecture solitaries, with a complex identity in the sense of the context and specific position. National Centre is for example one of them, a multi-purpose building from 1904 designed by Max Fabiani. As a symbol of Slovenian presence in the city has been a thorn in the Italian nationalists and fascists, who had therefore attacked, burned and destroyed it in 1920.

National Centre hosted a theatre, a printing house, two cafes and a hotel. It was burned on July 13th 1920. | Photo via Slomedia

We might find a track of the demolishment of the building in Srečko Kosovel’s poem The Ecstasy of Death, where the poet captured the moment of burning the symbol of the tolerance:

“Barely born you are already burning in the fire of the evening / All the seas are red, all the seas and lakes / full of blood, there’s no water, / no water to wash the guilt away, / for this human to wash his heart, / no water to quench this thirst / for the quiet green nature of morning.”

Slovene modernist poet Srečko Kosovel had not a bright side of the Europe’s future between two wars as dealing with nationalism, hate and fear. As a reaction of the Slovene community to the burning down the National Centre, the new Cultural Centre was built twenty years after WW II.

The foyer of Cultural Centre in Trieste. | Photo via Theatre Architecture

The multinational Trieste had the most important Austro-Hungarian port. With its strong ethnically Slovene rural hinterland, was prior to WW I the scene of increasing conflicts between the Slovene and Italian communities, both of which strove for supremacy in the city. After the Austro-Hungarian monarchy fell apart, the Italian army (Slovenes did not have an army of their own), occupied Trieste and a large section of Slovene territory.

The gulf of Trieste: left Koper, Slovenia, right Trieste Italy. | Photo via Wikimedia

With its militant policies it prevented the development of Slovene institutions in Trieste and further afield, whilst the existing institutions were systematically destroyed by Fascist groups. The expectations of Slovenes, who had fought on the side of the Allies, in connection with their role in Trieste at the end of WW II were high, but in 1954, following the London Agreement, they were not realized, Trieste was part of Italy.

Edo Mihevc was the author of the Cultural Centre in the 1960s, which is housing the Permanent Slovene Theater. | Photo via Twitter

Slovenian functionalist architect Edo Mihevc was in the forefront of Slovenian modern architecture after the World War II. He was one of Jože Plečnik’s students that separated from his method of artistic creation, thus embarking on a path of self-expression and search for harmonizing modernism, regionalism and humanist philosophy he designed a city solitaire - the Cultural Centre.

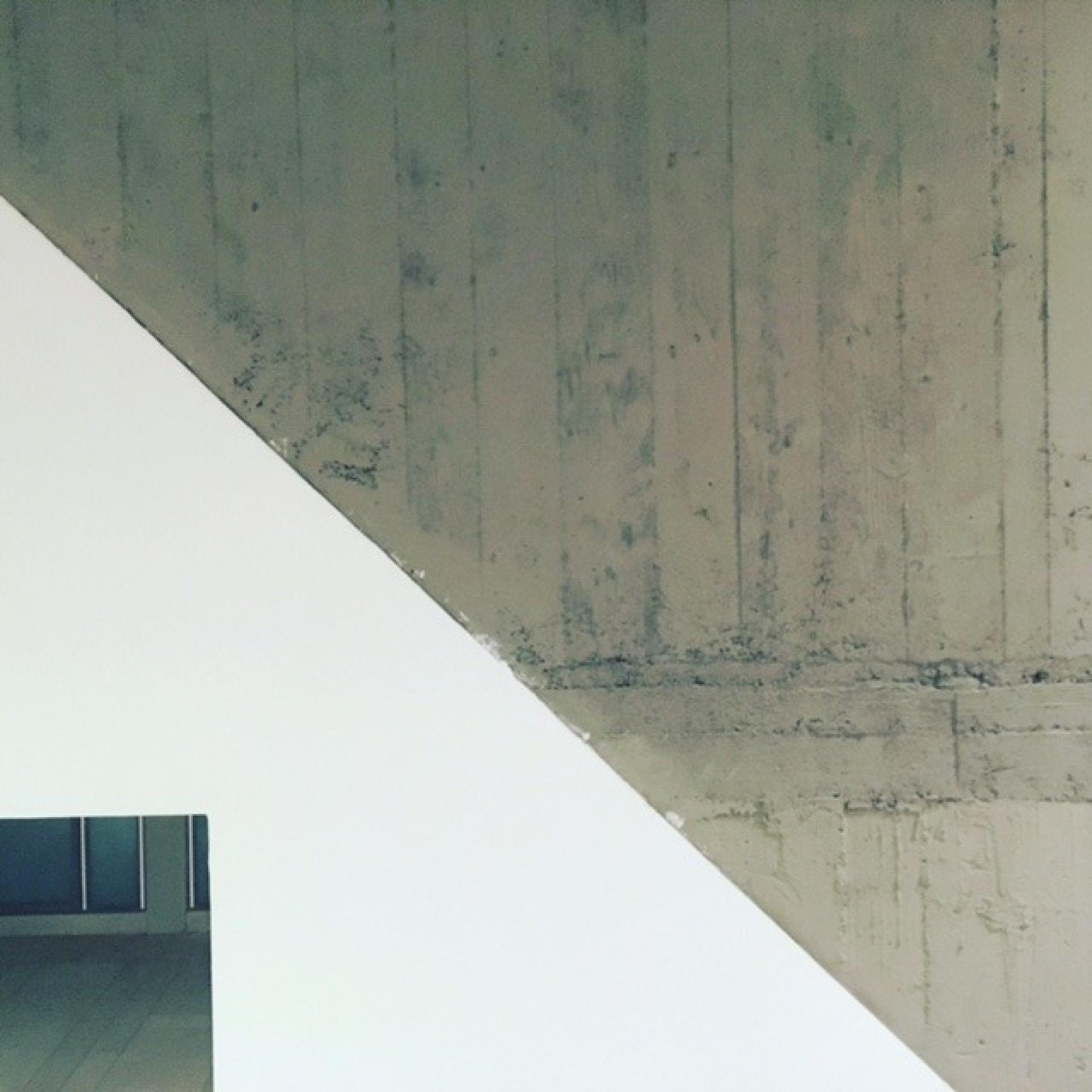

The view from Revoltella Museum rooftop was designed as the theme of the inner courtyard. | Photo via Museo Rivoltella

Focusing on buildings which are hosting culture, we definitely can’t overlook the Revoltella Museum, a modern art gallery founded in 1872 by Baron Pasquale Revoltella. The renovation of the building was committed to Carlo Scarpa. In this case he didn’t modify his design and correct it during the construction work as usual, his first concept was partly implemented by other architects. The rooftop area and the auditorium on the ground floor are the parts, which were most clearly implemented in the sense of work of Scarpa.

Play of the light in teh Revoltella Museum | Photo by Boštjan Bugarič

James Joyce was teaching at the Revoltella Business School before the Scarpa’s intervention as he emigrated with his wife from Dublin to Trieste. This was the city where he started to write his Ulysses.

Joyce lived at Ponte Rosso and attended Greek-Orthodox religious services.| Photo Via Museum of Joyce

With the complex monologues from Ulysses, which might wander above the rooftops of the city, the flow is cut by the brutalist complex of the Rozzol Melara at the hill above the city. The building landed on the hill as an UFO, which has no connection with the city. The brutalist complex creates an independent village equipped with all basic needs. In this way stands isolated from the rest of Trieste, a concrete solitaire.

Rozzol Melara follows theories of Le Corbusier. | Photo by Roberto Conte

As knowledge should be the most important value for the city it’s obvious to check how is defined the space of education, the university. The main building of the University of Trieste is symbolically positioned above the city. The rationalistic object proudly represents the medium-sized university founded in 1924. Before World War I, when Trieste was still a part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, the Italian-speaking population strongly supported the idea of building a university in the town, but Austrian authorities repeatedly rejected the proposal.

University building in Trieste. | Photo via ACCUSIM

After the war, Trieste was put under the joint control of the United Kingdom and the United States of America, in preparation for the establishment of a fully independent State, the Free Territory of Trieste, which nevertheless never came to exist. In 1954 Trieste was given back to Italy thanks to an agreement between the American and the Italian governments.

The statue of Minerva, the Roman goddess of wisdom and sponsor of arts, trade, and strategy at the wall of the university building. | Photo via pintrest

It make sense to conclude this voyage between two worlds with an unusual story from the literature; Trieste was for Marcel Proust “a delicious place in which the people were pensive, the sunset golden, the church bells melancholy.” He dedicated the streets of Trieste to Albertine, one of his seventy-eight characters from In Search of Lost Time. Proust was a master of description but actually never visited the city. The city of melancholy evoked his intuition and his emotions wrote the city. Whenever standing in between two worlds, asking what is the right answer, this doesn’t bring us the right answer. Sometimes the world doesn’t understand or is not prepared to accept the message, the knowledge and the experience of the intuition.