FOMA 3: From Vardar To Triglav*: Yugoslav Ruins-In-Reverse

The third edition of Forgotten Masterpieces is reading in reverse the ruins of Yugoslavia. Curated by Miloš Kosec, which will take us in the past through the territory of forgotten and unfinished masterpieces: the Royal Villa in Bled (Slovenia), unfinished Museum of Revolution in Belgrade (Serbia), Home of Revolution in Nikšić (Montenegro), the Youth Centre in Split (Croatia) and the Government Building in Skopje (Macedonia).

* »From Vardar to Triglav« was a popular song in Yugoslavia during the 1980s. An unofficial anthem of the former state with folk melody from Macedonia celebrates the unity of Yugoslavia.

Vinko Glanz built his object on Plečnik’s fragments. | Photo © Ajda Schmidt

Former Yugoslavia was a state defined by the process of construction: it was always a project in the state of becoming, never quite convincingly pretending that it had reached its self-set ideals, be it as a unitary nation of three »tribes« of the pre-WW2 Kingdom of Yugoslavia or post-war socialist ideals of Brotherhood and Unity and self-management.

This is perhaps why the built expression of state ideology gained a peculiar unfinished character as well. There are only a few urban landscapes that could identify with Robert Smithson’s designation of a construction site as »ruins in reverse« as intensely as the decaying fragments of never finished Yugoslav projects. This is true in a literal sense, as many construction projects were never finished and as such became ruins and construction sites at the same time, being caught in the strange intermediary state in between nothing and something. But it is also true in a more allegorical sense as construction and decay of one and the same entity seem to mirror the schizophrenic reality that Yugoslavia tends to take in the minds of many of its former citizens: a recent, muddy and unsuccessful experience as well as an ancient, almost archaic ideal of a state long gone. Most superfluous manifestation of such archaism is surely the recent fascination with »brutalist« abstract masses of National Liberation Struggle memorials found in all of the former republics that often resonate as archaeological remains of a civilization long gone – a telling sign of the state of modernist ideals today.

Jasenovac by Bogdan Bogdanović is a reminder of the atrocities perpetrated in the Jasenovac concentration camp. | Photo via Jasenovac Memorial Site

I will take a parallel but different route. I propose a visit to the buildings that were conceived and constructed as expression of various unifying ideologies of Yugoslavia but were never finished. I’m interested in the difference between their projected ideal and their current reality. Undoubtedly it is too much to expect a psychoanalytical confession of a whole society from a couple of buildings. But sometimes it is more fruitful to try and read architecture through what has not been done and why, as opposed to merely what has been realized.

Interest in Plečnik’s work developed in the 1980s as postmodernism led to a reconsideration of classical forms and motifs in architecture.

Founders of first Yugoslavia found themselves with the daunting task to assemble extremely diverse nations and religions into a unified state. The favorite expression of the age was to “forge” Yugoslavia as if from fire and iron of a smithy. King Alexander saw himself as the decisive institution of this process; when he proclaimed dictatorship in 1929 he formally announced the existence of a single Yugoslav nation, comprised of three constituent “tribes”: Serbs, Croats and Slovenes. But the state still lacked any visible expressions of this newly-invented policy. When on a state visit to Czechoslovakia he found himself admiring the recently reconstructed presidential residence at Prague Castle that had turned the feudal Habsburg residence into a symbol of a new, progressive and democratic nation, he was surprised to learn that the architect responsible was his own subject, Slovene Jože Plečnik.

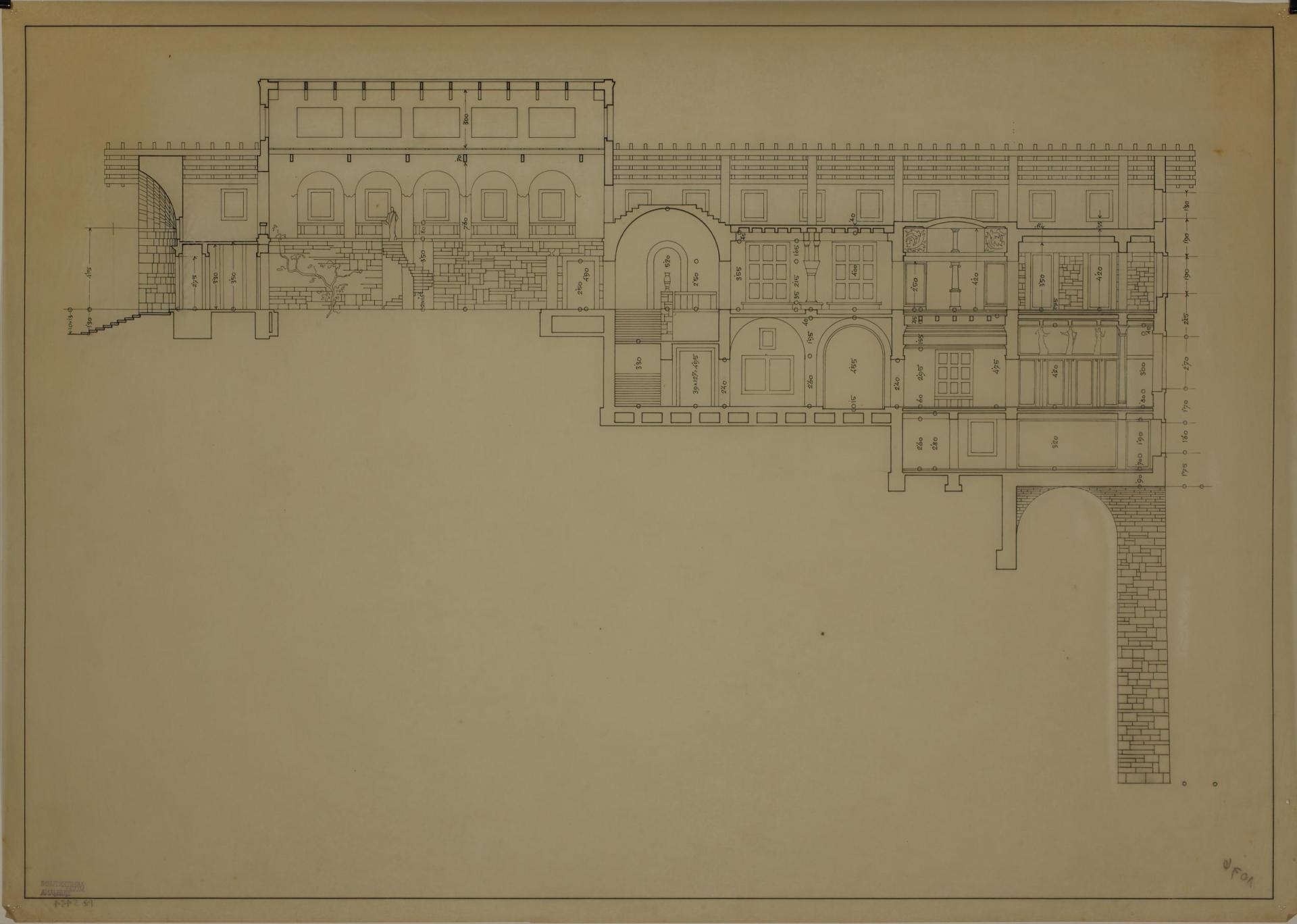

Alexander had bought a large estate by the lake of the Alpine resort town of Bled that has served as a de facto royal and governmental summer residence during the interwar years. This is where Alexander and Plečnik began to plan a tangible expression of the new Yugoslav monarchy, an ideology of stone. On the part of the steep lake shore Plečnik had constructed three mighty stone pillars that would have carried a uniform monumental mass of the New Royal Villa as if it was breaking away from the slope, floating directly above water. This would create a new picturesque element capable of competing with the venerable medieval castle on the opposite side of the lake, but it would also materialize King’s unifying new ideology: the royal structure supported by three pillars could be read as Yugoslavia supported by the three “tribes”. But in 1934 when the pillars were slowly rising from the ground Alexander was assassinated in Marseilles. The building was discontinued and the three pillars that ended up carrying nothing at all stood as an architectural allegory of the political confusion of the country.

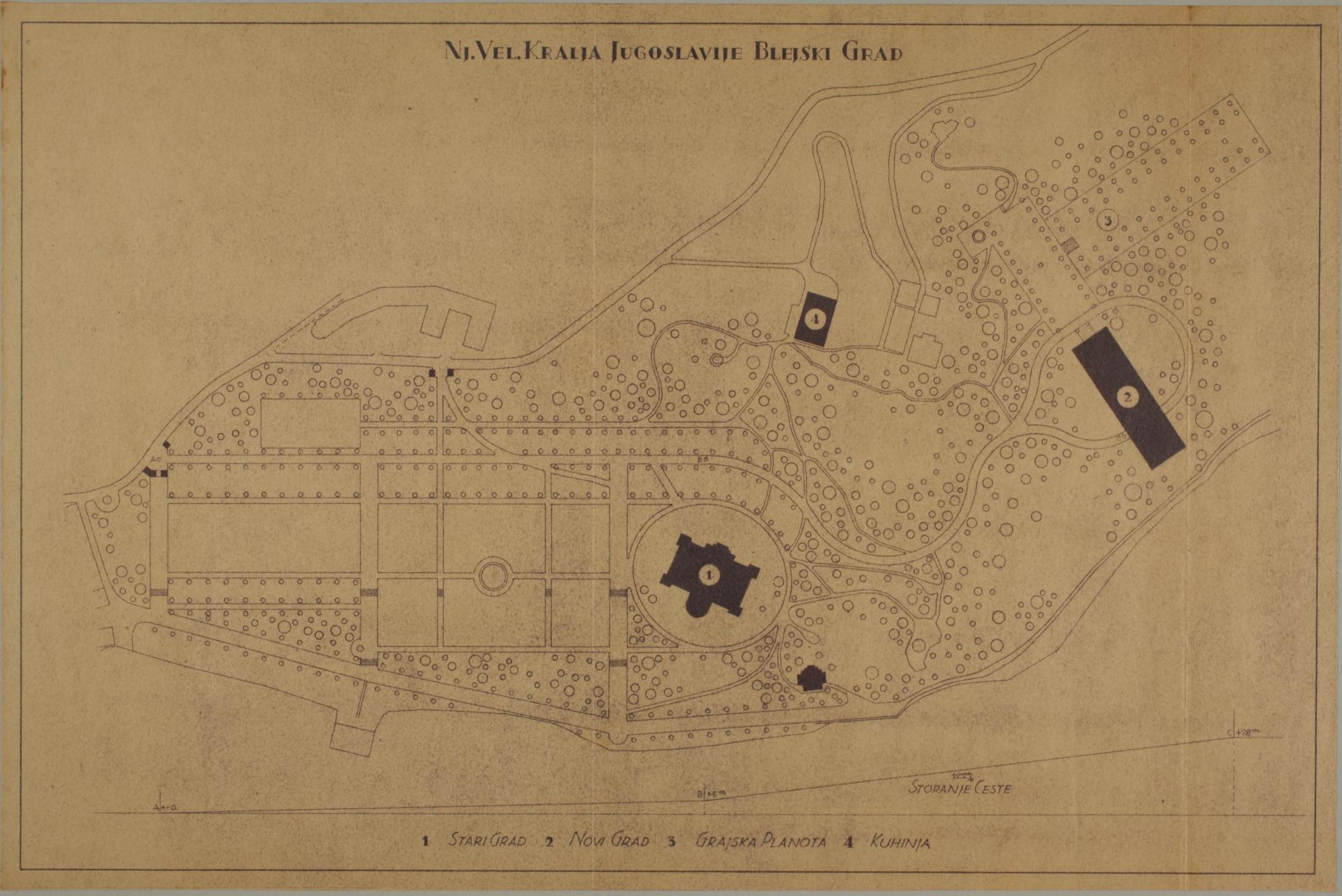

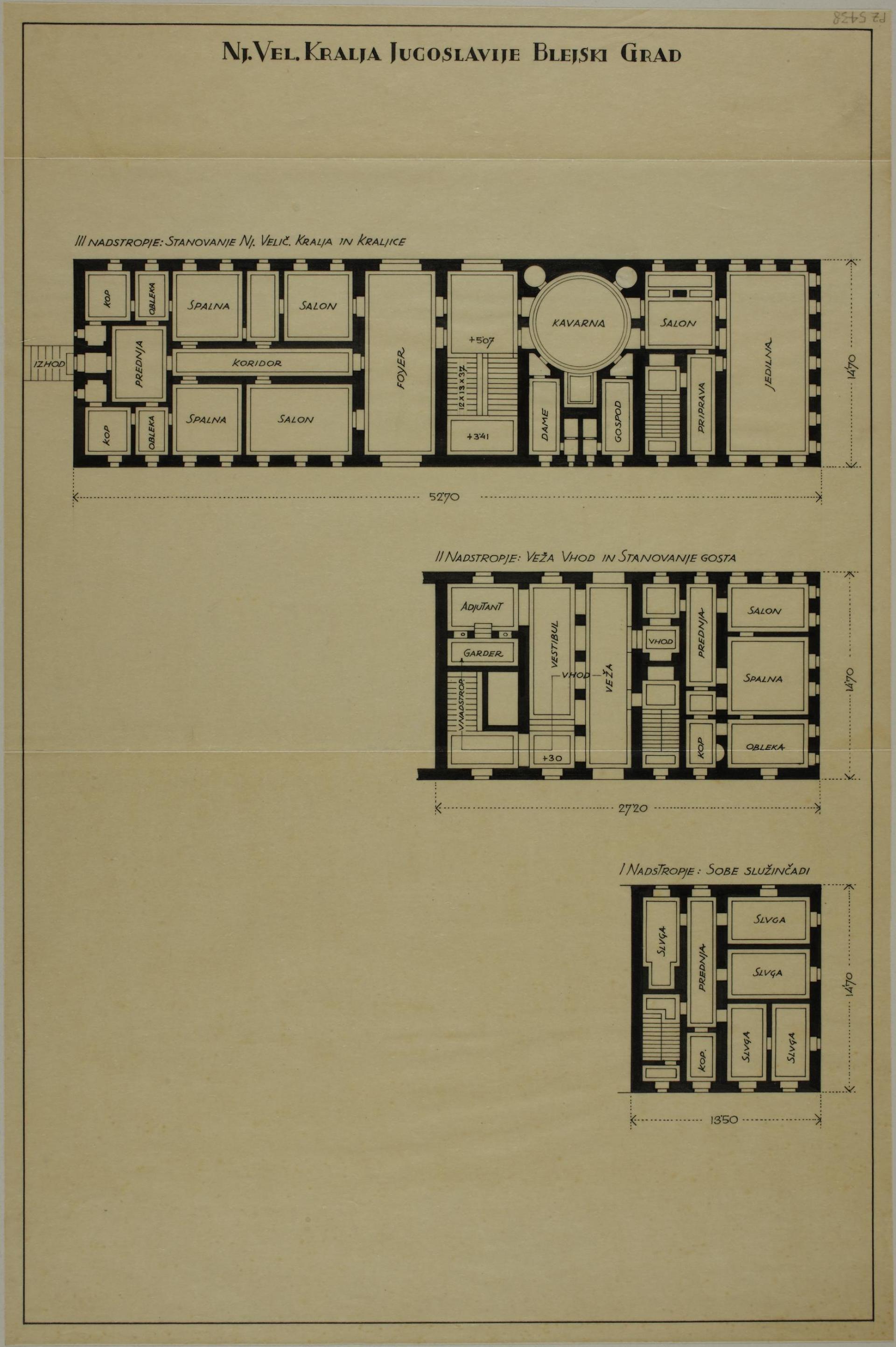

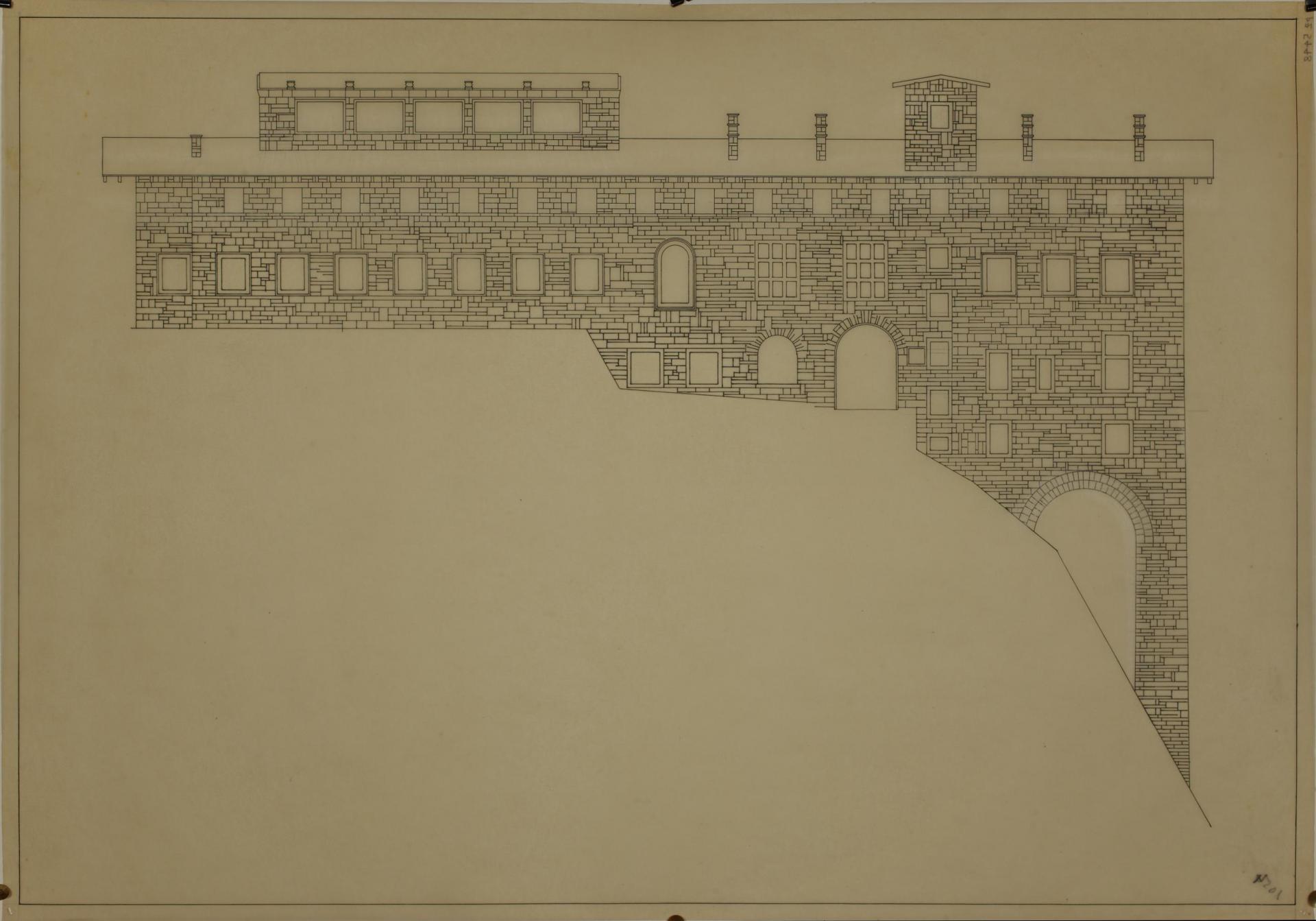

The original project plan of never constructed villa from the Plečnik Collection by Museum and Galleries of the City of Ljubljana. | Photo © MGML Documentation

One decade, one World War, one Civil War and one revolution later a new Yugoslavia was being constructed out of the rubble of the old one. Once royal Bled domain was now taken over by President Tito; the new establishment wasn’t keen on completing the King’s project but did reinterpret it in its own way. Plečnik’s pupil Vinko Glanz used his teacher’s monumental base for an almost diminutively small presidential teahouse, creating a perpetual takeover of the royal non-finito; an architectural as much as political stance on (dis)continuity with the past.

The Tea House with the view by Vinko Glanz. | Photo © Ajda Schmidt

The new state preferred tabula rasa to continuity; this is why the new federal government district wasn’t planned in the old capital of Belgrade but on reclaimed marshlands on the other side of the Sava River. In 1960s the construction of the Museum of Revolution, a sort of official ideological vestry of the socialist state, was begun. The celebrated Croatian architect Vjenčeslav Richter conceived a daring modernist design on eight concrete columns (if we were to push our allegorical reading of the architectural form a bit too far we could link them to six constituent republics and two autonomous regions of the new federal state).

The somewhat static core of the structure, floating among the New Belgrade greenery, was to be crowned by a dynamic tent-like roof. When ideological fervor and money ran out in the 1980s only the base of the structure was completed. Out of it the eight rusting steel armatures still reach to their original height, almost as ghosts of the eight missing columns. But this construction site that became a ruin is nevertheless inhabited: a group of Roma living in the cave-like and crumbling base confers an almost uncanny quality to this post-apocalyptic site. Observing drying laundry fixed on concrete ideals, a new archaism meets the modern past.

Remains of the Museum of Revolution in New Belgrade | Photo © Miloš Kosec

The 1980s were the years of financial and political crisis, but somewhat paradoxically, also the years of some of the grandest ideological architectural manifestations. Maybe as a kind of architectural overcompensation? Revolutionary traditions (an oxymoron in itself) were poured into concrete at the time when they were losing their battle against conflicting nationalisms and market economy that were slowly creeping in. What was a conceptually impossible task also became a tragic one both because of ambitions of the plans as well as inability to complete them. Perhaps there is no single better example of this decadent phase of monumentalism than the Home of Revolution in Nikšić, Montenegro. The grey masses of an over dimensioned post-modern cultural home extending from the deep cellars to the authoritative tower that holds sway over the small mining town were designed in the 1970s by the young and emerging Slovene architect Marko Mušič.

Home of Revolution was presented in the context of Montenegro Unfinished - Treasures in Disguise | Photo © Luka Bošković

In the late 1980s the construction was called to a halt as the revolution that was to be housed in the building disappeared from speeches and budgets of the politicians. The fenced-off “ruin in reverse” in the centre of the town remains caught in between past and future – a dangerous state full of symbolic and real abysses that have in the past 30 years claimed 16 lives. Recent architectural competition that was won by the international group of HHF and Sadar + Vuga architects gives hope that the future does not lie necessarily in choosing either to complete or demolish the strange thing. Battling with one’s symptoms sometimes means to live with (in) them.

The Youth Centre in Split was presented at the Croatian Pavillion of the XV. Venice Biennial. | Photo via we need it – we do it

A similar sentence of a being caught in-between has been fated to another building from the same period: the Youth Centre in Croatian coastal city of Split. After ambitious plans by the architect Frane Grgurević were discontinued the half-completed building became another allegory as well as a very real security and financial burden to the city. But Split has a long tradition of architectural reinvention and reincarnation. The famous Diocletian’s Palace built by the Roman emperor as his private residence was in the middle ages reinvented as a walled city, proving the durability of materiality over ideology. In the post-Yugoslav transitional reality a somewhat similar process of reinvention took place with Youth Centre, controlled by the Coalition of Youth Associations. What the hermit crabs that are using discarded shells as their portable houses knew all along and what medieval population of Split realized through the re-use of ancient Emperor’s Palace was proven yet again: the persistence in using a half built, half ruined building is not only pragmatic, but also highly creative. But in a region that has accumulated an excess of historical breaks and fractures this became a powerful statement of reconciliation with the past as well.

Original building designed by Peter Mulichkoski. | Photo via Yomadic

But precisely the renovation that was conceived as a part of the ambitious and controversial project “Skopje 2014” grants it its place in this small cabinet of post-apocalyptic curiosities. Perhaps as defining for the architectural history of Skopje as the famous 1963 earthquake, the ruling party’s plans reinvented the brutalist fabric of the city into a newly-antiquated capital of “Ancient Macedonia”, proliferated with third-rate sculptures and post-neo-classicist plaster facades on public buildings.

The three break points from Macedonia Unfinished defines the architectural situation in Skopje. | Photo © Siniša Jakov Marušić

A decent if not exceptional modernist architecture was therefore forced to take on the clothes of new barbarism. A retrograde transformation of the finished building into an allegorical if not literal plaster ruin-in-reverse seems like a suitable terminal stop. This is where a fleeting elegy perhaps sensed in the unfinished royal villa at Bled erupts in a banal, turbo-folk inspired crescendo.

Miloš Kosec is an architect, editor and publicist living and working in London and Ljubljana. He graduated from Faculty of Architecture of University of Ljubljana in 2013 with the Master's thesis Ruin as an Architectural Object, for which he received Plečnik and Prešeren award. He has started his PhD research project on passivity of contemporary architects at Birkbeck College, University of London in 2016. He is also a practicing architect and landscape designer, member of the Kabinet architecture group. He is a member of the editorial boards of Praznine, Journal for Architecture, Art and Spatial Culture and Outsider Magazine. He had been nominated as one of the jurors in the international competition for the reuse of the ruin of the Home of Revolution in Nikšić, Montenegro in 2016. | Photo © Stine Alling Jacobsen