Teatro del Mondo: An Odyssey

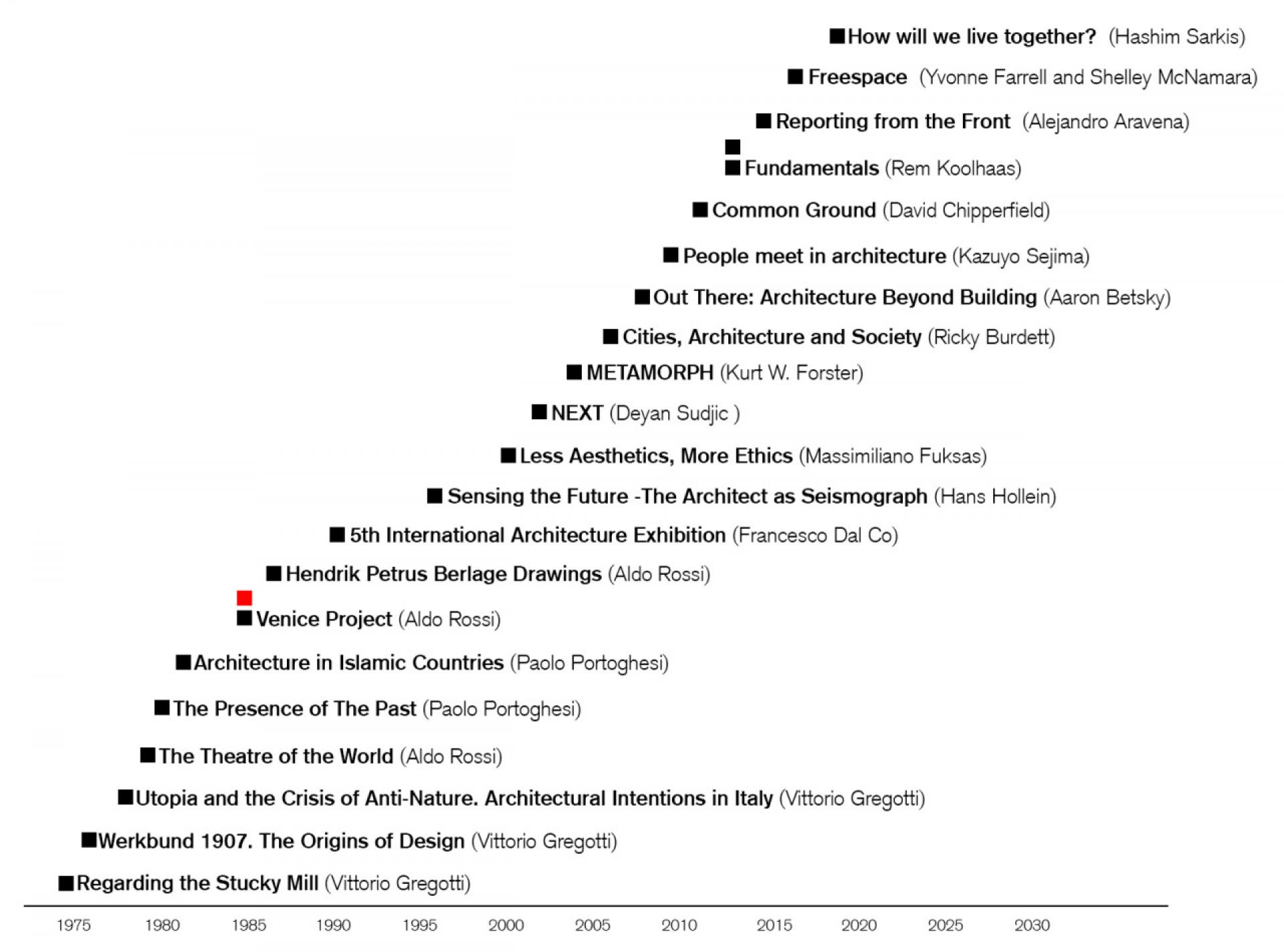

The Venice Biennale is an increasing magnet for professionals and laypersons alike, as evidenced by a stampede of hundreds of thousands of visitors quickly rolling over exhibitions in Giardini dell’Arsenale, and an exponentially growing number of various minor events during the Mostra.

Arnell, Peter and Scully, Vincent (1985): Aldo Rossi-Buildings and projects. Rizzoli International Publications, Inc. New York.

People from all over the world travel to Venice to visit the Biennale. But it happened just once that a pavilion intended for Biennale went in the opposite direction. The motives for this voyage were reported on the sidelines of an exhibition, La Biennale di Venezia 1979-1980: The Theater of the World Singular Building. Maurizio Scaparro curated the show that was held in Ca’ Giustinian in 2010.

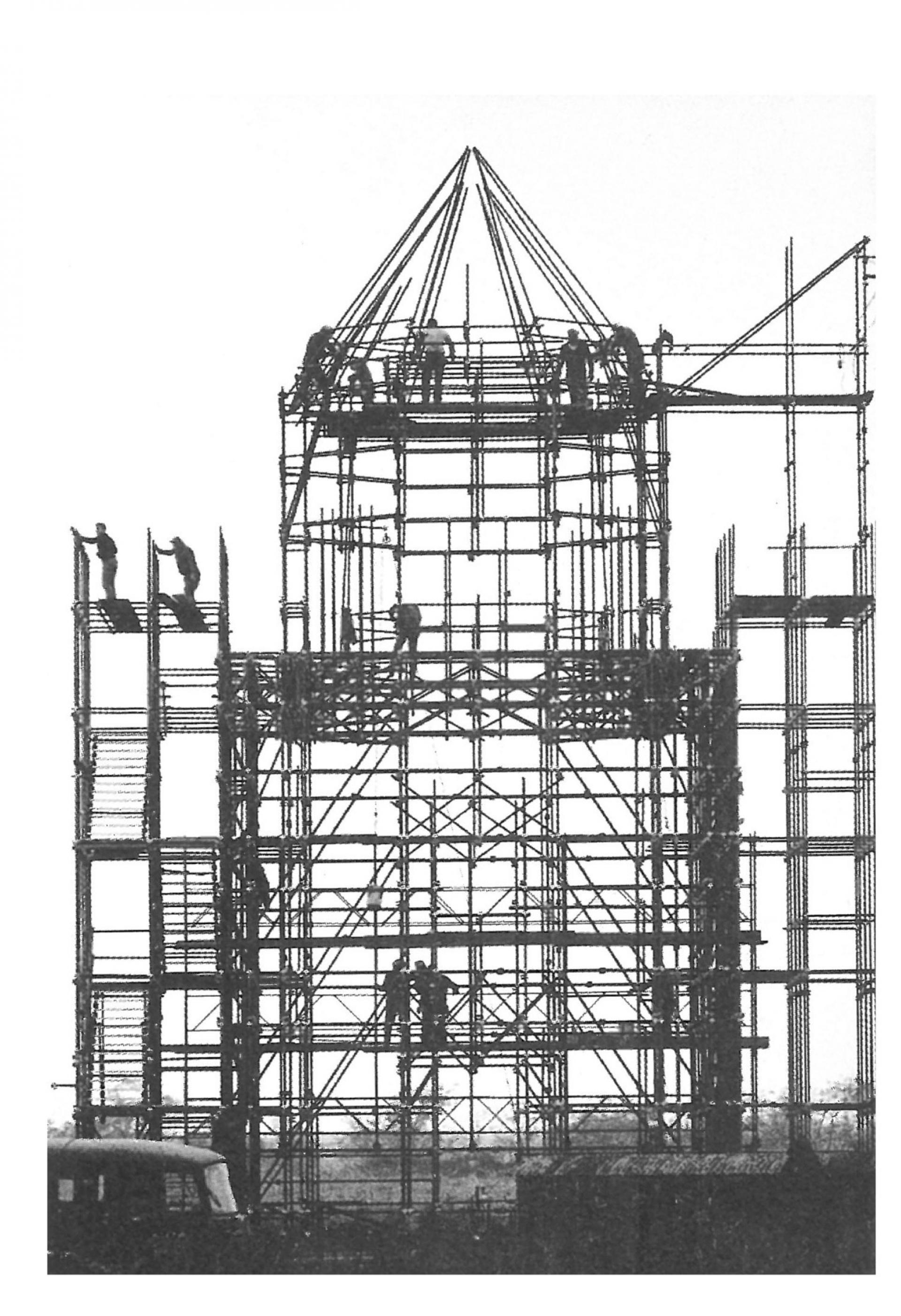

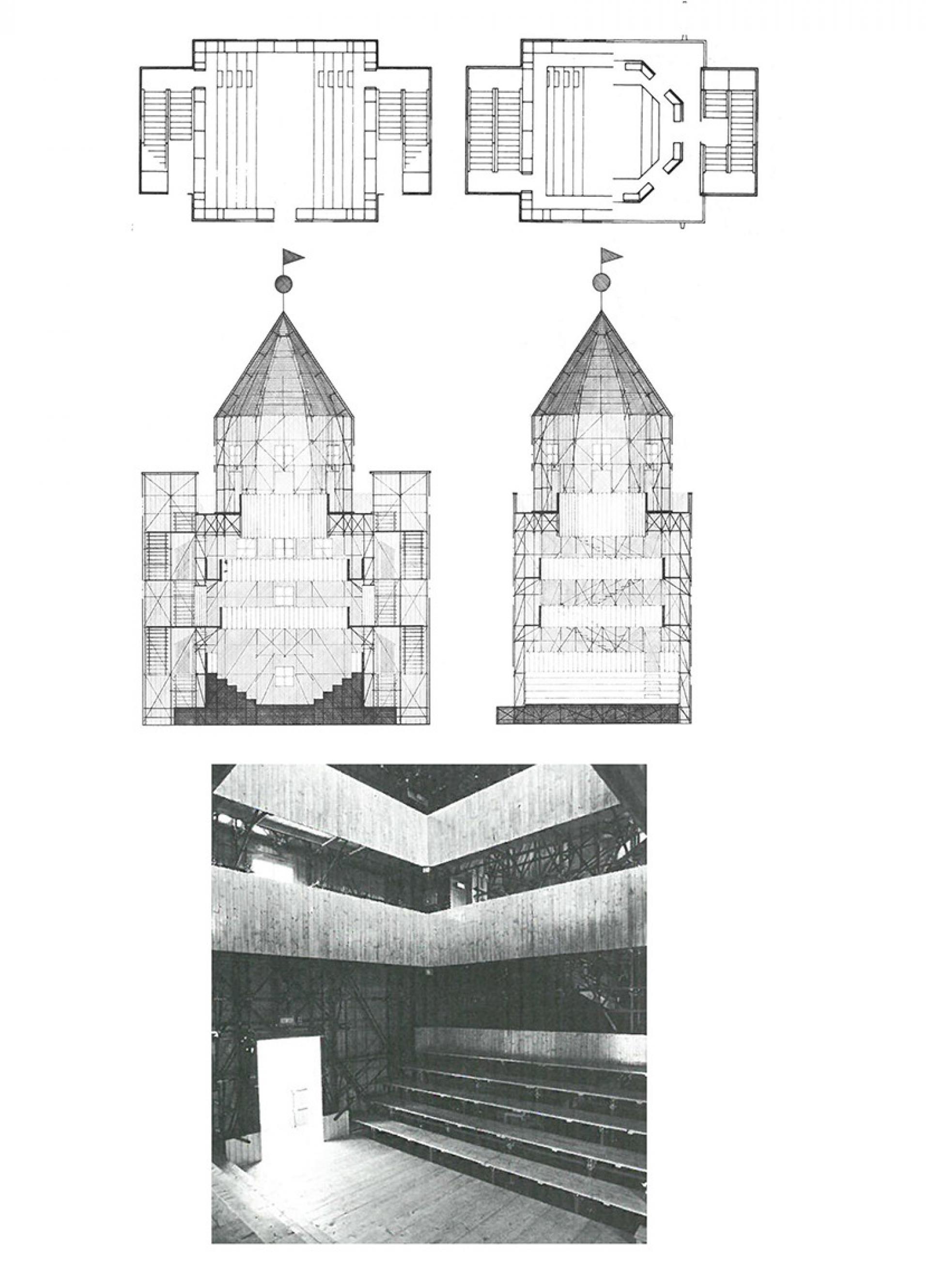

It is always difficult to judge a piece of great contemporary architecture: From the vantage point of present, we usually lack proper temporal distance. But 30 years after its implementation, Il Teatro del Mondo (The World Theater) - a floating building designed by Aldo Rossi for the architectural Biennale once anchored in front of Punta della Dogana and created in 1979 for the Venice and the Stage Space exhibition, grew to become an architectural icon.

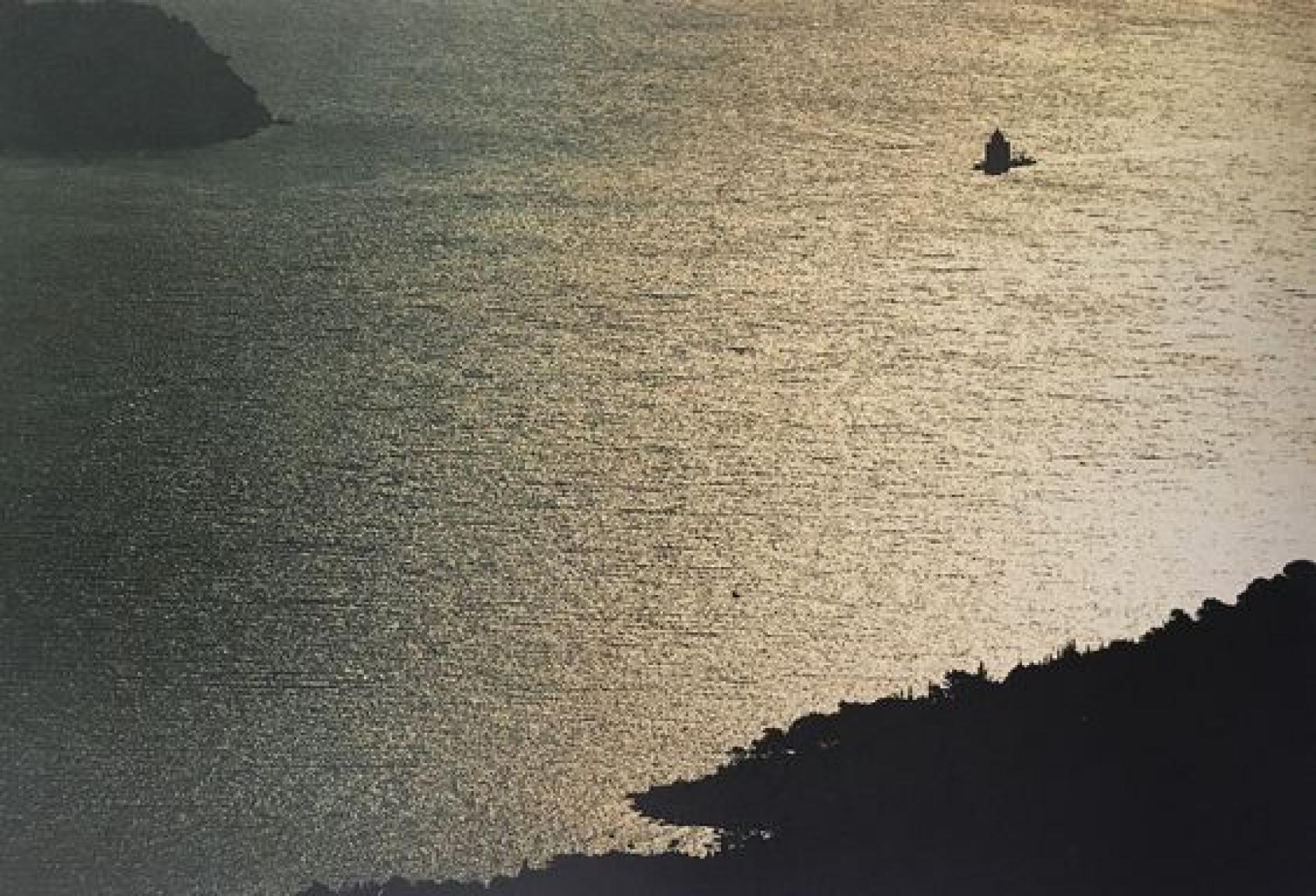

Il Teatro del Mondo by Aldo Rossi | Photo via Focusdamnit

British theatre director Edward Gordon Craig once said: “There is something so human and so poignant to me in a great city at a time of the night when there are no people about and no sounds. It is dreadfully sad until you walk till six o’clock in the morning. Then it is very exciting.”[1] In his stage designs, Craig used architectural language to design and articulate the relationships in space between movement, sound, line, light, and color, enabling actors to assume positions and spatial relationships that they could use in ordinary urban life.

A parallel to Rossi’s architectural project is unmistakable - was that a coincidence or intention?

Venice-Dubrovnik, a diary of the international theatre lab 1980 from “Giornale di Bordo”. | Photo © Daniela Sacco

In Dubrovnik | Photo © Piero Casadei

Its legendary trip to Dubrovnik, (the theater was ferried in the summer of 1980 to the local Theatre Festival) is exciting and feels like reading Homer’s Odyssey. In the best tradition of Venetian mobility, Rossi wrote: “Just the image of Venice, a synthesis of gothic and misty landscapes and oriental inserts or transpositions, fixes the capital of the city on the water. Therefore, of the possible passages, not only physical or topographical, between the two worlds. Even the Rialto bridge is a passage, a market, a theater. ”[2]

Arnell, P. and Scully, V. (1985): Aldo Rossi-Buildings and projects. Rizzoli International Publications, New York.

oday, when we think about Venice, we conjure up a small peninsula in the northern Adriatic. It is hard to imagine that Venetians were able to rule such a vast cultural space. The key was their legendary mobility. They were always on the move. The Republic built on the water developed its eclectic cultural influence through its enduring presence in the Adriatic and the Mediterranean. The city was the final destination for the most important cultural and caravan route between the Orient and the Occident. No wonder The World Theater united in itself several references: Renaissance and Elizabethan theaters, lighthouse architecture, Venetian floating architecture, and temporary structures built for the carnival. [3] As Nadine Labedade wrote "Thus, it is the typology of the city that creates the scenario. And this mobile theater-boat became a fragment of the urban history, a quasi-metaphysical image tasked with representing architecture.”

The revision of modernity - as an abstract, functionalist, and timeless architectural language - was a common denominator of the Tendenza, the group formed by Also Rossi together with Carlo Aymonino, Paolo Portoghesi and Franco Stella among others. Rossi was undoubtedly the most influential member through his book L’architettura della città (The Architecture of the City, 1966). Through descriptions of Italian cities, he described his concept of architecture. He saw his work as part of an urban structure in constant dialogue with the countless layers of history, a city in continuous change in analogy to its buildings, and adapting to new social, economic, and cultural conditions.[4] His design language is generally understandable, using simple geometries and academic elements borrowed from the past. His layouts reintroduced imagination and poetry into the presentation of architectural work: colorful collage, wooden models, the mixed scales of shapes that can be both design objects and real houses.

There were just a few performances in the floating Teatro del Mondo that Rossi built for the Venice Biennale in 1979. After the short display in the lagoon and the voyage across the Adriatic to the Croatian city of Dubrovnik, the temporary theatre was disassembled. Nevertheless, this scenography-like building shaped the Italian architecture of the second half of the 20th century like no other project. The relocation to Dubrovnik, the famous medieval Republic and archrival of Venice in the Adriatic, inspired discussion about eclectic cultural influence and the complex historical layers of Adriatic cities. Those years coincided with the beginning of the Postmodern movement in former Yugoslavia. It probably was not Rossi’s primary focus of attention, but this Trojan Horse disguised as a theater that was shipped to Dubrovnik, was the first step in a politically delicate debate and movement towards a revision of Modernism in Yugoslavia - no easy feat in the ideologically colored cultural character of a country unconditionally committed to Modernism. Theater as a revolutionary tool in urban planning? Notabene: in 1956 the city of Dubrovnik even hosted CIAM X, the congress. which saw the start of the Team 10.

Peter Brook, who directed Hamlet in Dubrovnik, said that “a theatre should be like a violin, its tone coming from its period and age”.[5] His daughter Irina took her Midsummer Night’s Dream to the Old City of Dubrovnik’s Marin Držić Theatre, one of the oldest institution of its kind in Croatia.

Arnell, P. and Scully, V. (1985): Aldo Rossi-Buildings and projects. Rizzoli International Publications, New York.

The Dubrovnik Shakespeare Festival was founded in 2009 by American-Croatian author Michael Lederer. Suddenly, Dubrovnik and its architecture are increasingly associated with the stage on which everyone plays a distinct role in his or her daily live. On an urban scale, the morphology of the Old Town itself reminds us of a stage, surrounded by the natural slopes of the adjacent hills, with the eternal blue of the Adriatic in the back. The topography places the architecture in the foreground and the architecture has taken over the nature so dramatically that the two have become indivisibly connected.

Finally, Rossi´s vision worked out: cultural and geographic lines connected the Adriatic cities together over the last decades. The voyage of the Teatro del Mondo can coincidentally be seen as a rediscovery of the medieval stage setting of Dubrovnik, which serves as shooting location for renowned TV-series and a dream destination for thousand of tourists. Rossi must have had the words of Japanese playwright Yukio Mishima in his mind when he said that life is nothing but a theater. [6]

Mladen Jadrić is teaching and practicing architecture in Vienna, Austria as the principal of JADRIC ARCHITEKTUR. He has realized a wide range of projects of different scales: architectural and urban design projects, housing, residences, art installations and Museums in Austria, USA, Finland, China and South Korea. He is teaching at the TU Wien and has gained extensive experience as a visiting professor and guest lecturer in Europe, USA, Asia, South America and Australia. His work has been awarded the Outstanding Artist Award for experimental tendencies in architecture in Austria. He is also a member of the Künstlerhaus in Vienna, and deputy Section Chair of the Federal Chamber of Architects. | Photo © Jakob Mayer

Notes:

1. E. G. Craig (1998): A Vision of Theatre, Christopher Innes, York university, Ontario, Canada.

2. 1998 OPA N.V. Published by license under the Hardwood Academic Publishers imprint, part of The Gordon and Breach Publishing Group

3. Observations on the Fantastic Nature in the Architecture of Aldo Rossi, Alessandro Dalla Caneva, Architectoni.ca 2018, Online 4

4. Rossi - Autobiografia scientifica, Milano, Nuova Pratiche Editrice, 1999

5. Eyre R. (2004): National Service: Diary of a Decade at the National Theatre

6. Mishima Y. (2018): Bekenntnisse einer Maske, Kein&Aber, Zürich