Skopje 2020

Skopje, the North Macedonia capital, has changed regimes and countries. From the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes to Yugoslavia or FYROM. Besides the demolishment of almost 80% of the city during the earthquake in 1963, has the most brutal demolishment occurred in last ten years, after its project Skopje 2014 was executed.

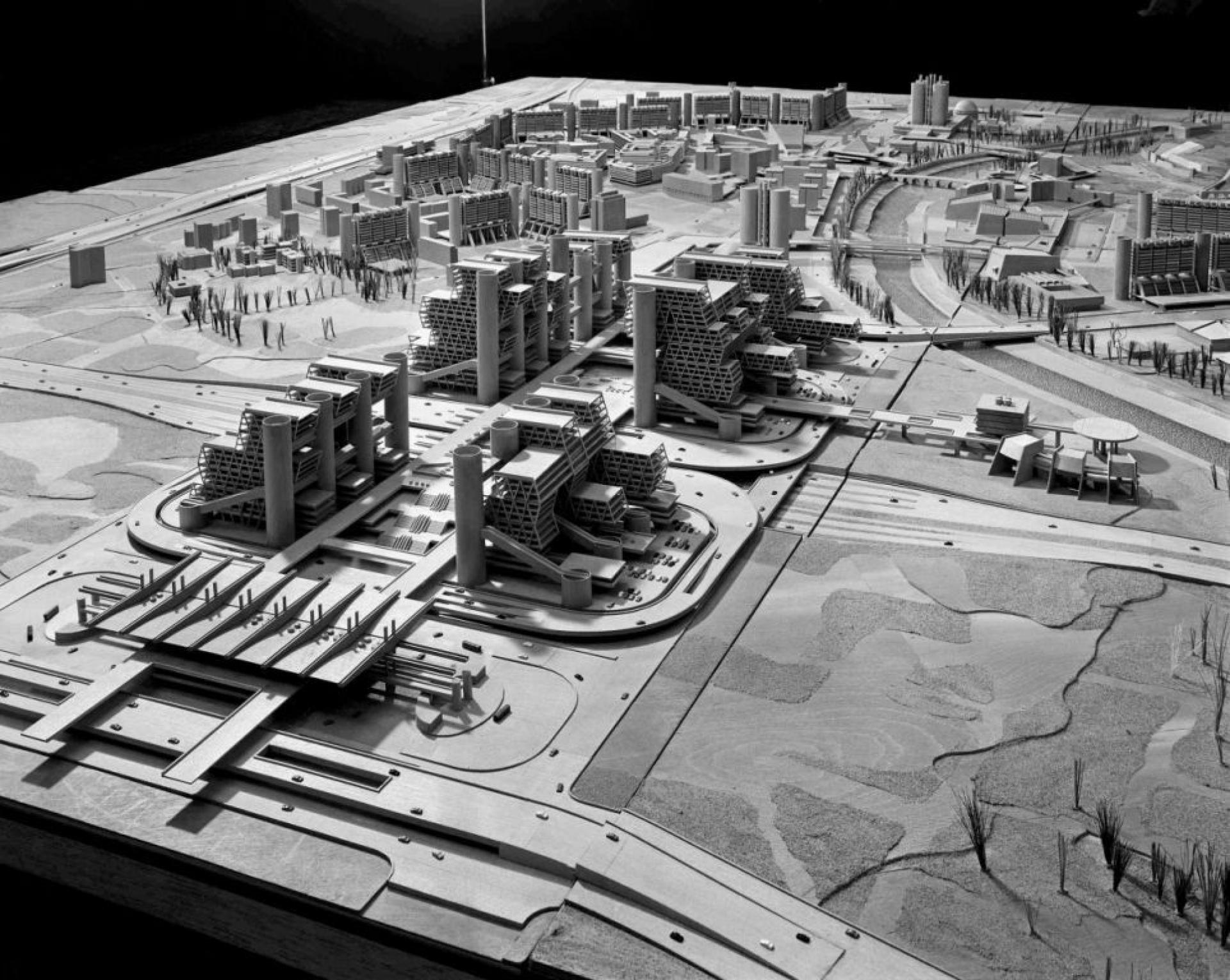

Kenzo Tange’s model for the central area of Skopje. | Photo via Bakalchev

Architcetuul already revealed Skopje’s story several times; from Macedonia Unfinished: The Tree Break Points (2014) to the Skopje Unfinished 2014-2018 from the Venice Biennial (2018). This time we talked about Skopje with the curatorial advisory board Ana Ivanovska Deskova, Vladimir Deskov and Jovan Ivanovski from the MoMA exhibition Toward a Concrete Utopia: Architecture in Yugoslavia, 1948-1980.

Poster for the retrospective exhibition of the architect Janko Konstantinov (1984). | Personal archive of Jovan Ivanovski

What happened in Skopje in 1963?

VD: Skopje was struck by an earthquake of catastrophic proportions in July 1963. There were over 1.000 casualties, more than 3.000 people were injured, while 75% to 80% of the urban tissue was either demolished or damaged beyond repair. What followed after this unfortunate event, was actually a case of unprecedented international solidarity. More than 80 countries gave their donations in many different forms, from the most needed immediate supplies, financial aid, different kinds of intellectual help and expertise, all the way to art pieces or architectural designs. Help started to come immediately after the earthquake and continued for a decade.

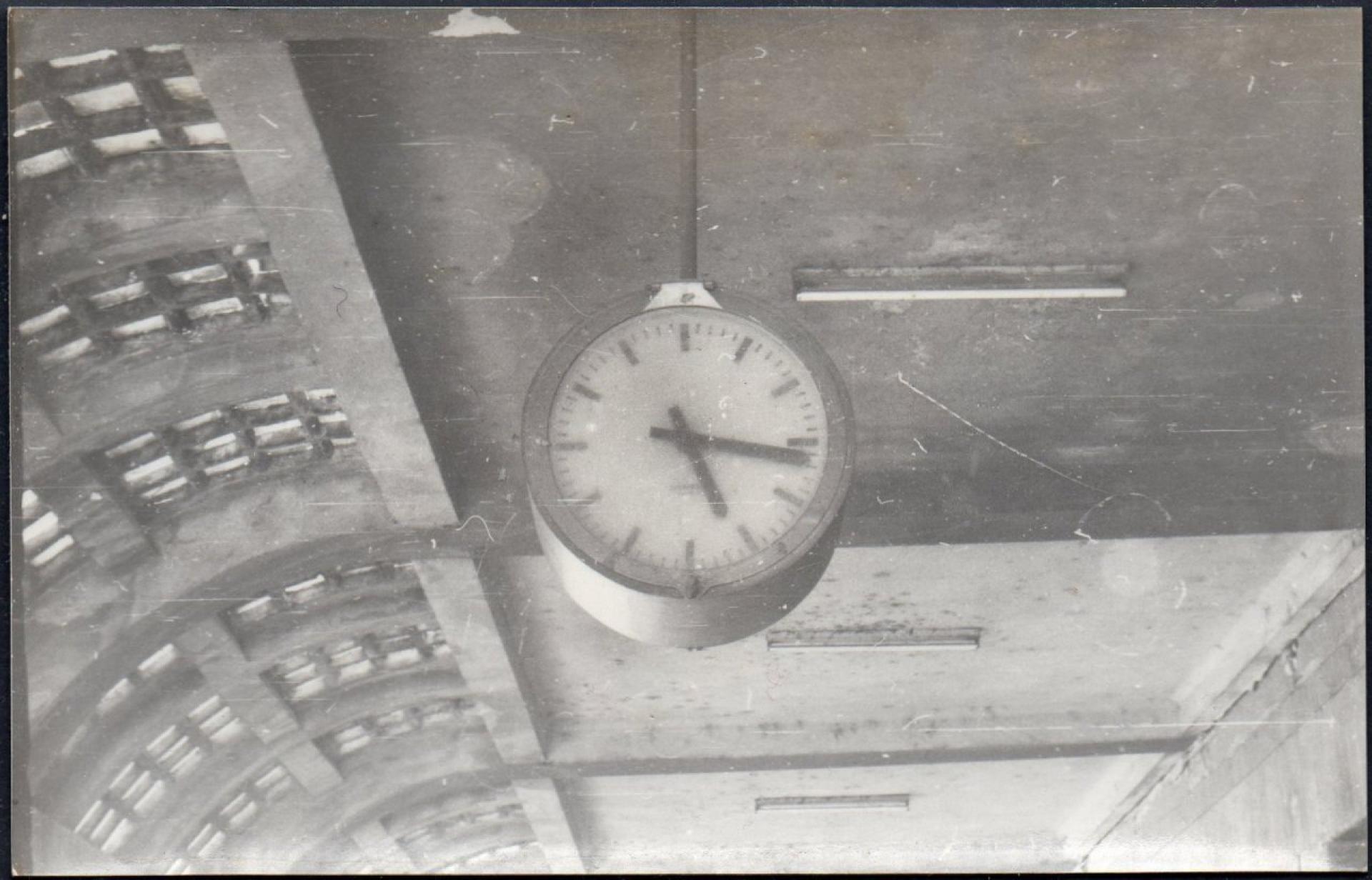

The clock at Skopje railway station stopped at 5:17am, when the first wave of the earthquake hit the city of Skopje in 1963. | Photo via Paperheritage

After the first shock, the natural disaster became a trigger for radical transformation of the city. Previous peripheral, local and unknown Skopje, suddenly became a spot where famous architects and planners worked together with architects both from Macedonia and other parts of former Yugoslavia. The whole reconstruction process was guided by the UN. Ernest Weissman, the former CIAM member was appointed as a Chair of the International team, Adolf Ciborowski from Poland was project manager of the Master plan, Doxiadis Associates from Athens were involved, as well as many other international experts.

Kenzo Tange team in front of their model of the eastern area of the city centre of Skopje. | Photo via Templates of consumption

In 1965 as a joint effort of the UN and the Yugoslav government, a very interesting invited competition was launched for the Skopje city center for an area of 2x2 km. In the reconstruction plan for Skopje four Yugoslav and four international teams participated. The prize was divided; 60% went to the Japanese architect Kenzo Tange and his team, whereas 40% were awarded to the Croatian architect Miščeviċ and Venzler.

The urgency of the post-earthquake condition in Skopje and the specific phenomenon of rapid construction could be compared to the post-World War II situation in many European cities; the need for rational solutions, the use of industrially produced elements and economical construction methods. As a consequence and result, the relatively short but high in intensity period of 15 years brought the undoubtedly most powerful architectural segment within Skopje’s recent architectural history.

What happened in Skopje in 2014?

JI: If you refer to the Skopje 2014 project, it started several years earlier, in 2009, a short video was launched on the national television showing the development and transformation of Skopje into a new national capital. No one could believe his eyes at the time. In the years to come, it turned out to be our unavoidable reality.

Neo-baroque facades over the River Vardar. | Photo © Maja Janevska Ilieva

Skopje 2014 was a decadent project, highly political in nature, that damaged the city tissue to a great extent, probably the biggest disaster the city had after the earthquake. Once again, the project saw the architecture as a tool for representation. The unwanted modernist (socialist) heritage was supposed to be erased and replaced with strange eclectic (supposedly neo-classical and neo-baroque) structures. The size of the project is huge; new buildings were erected; existing buildings were changed (new facades have been made), some of them real masterpieces of the post-war or post-earthquake architecture; numerous sculptures have been placed all around the city center, together with ridiculous structures in the riverbank of Vardar, such as ships and panoramic wheel.

What is color revolution?

AID: In April 2016 there were mass protests against the government. Thousends of people were walking and demontrating in front of the Parlament and the Government building. At certain point some of the protesters started throwing paint on the governmental buildings as well as on the buildings and sculptures of the project Skopje 2014.

Colorful Revolution. | Photo © Maja Janevska Ilieva

Skopje 2014 was the major project of the previous government and the former Ministry of Culture. Therefore targeting its results and staining them with color bombs was a symbolical and powerful yet peaceful way of showing dissatisfaction and revolt. Many buildings were target; the Ministry of Culture, the Government (previous modernist building re-clad in eclectic mixture of styles), the new Archaeological Museum, the Triumphal Arch. The media’s described it as a colorful revolution and it became a symbol of the protests.

What happed to the city of Skopje in last few years?

VD: There is an intense construction activity going on, mainly housing. The city is densifying, practically every single gap has been filled in. In many settlements, the existing building plots have been enlarged and extruded to height, which the city can not sustain. Therefore one could not find much quality in it. Regarding the city center, the previous activities with Skopje 2014, has been stopped. At least nothing new has emerged; however nothing has been knocked down or disassembled as well.

How do you encounter values of the modernist legacy?

AID: In the past 10 years we have conducted an extensive research on the architecture of the 20th century in Skopje, especially the post-war architecture. It was based upon our individual interest in this segment of the architectural history about the city of Skopje, which is an interesting architectural and urban case per se. This interest coincided with the increasing global interest for the post-war and late-modern architecture.

The first major international presentation of the modernist legacy in Skopje was the project Findings on the 2014 Venice Biennale, which was created by a wider group of architects, mainly colleagues from the Faculty of Architecture in Skopje. Later, the three of us conducted several other research projects: Biography of an Architectural work: The Telecommunications center Skopje – architect Janko Konstantinov (2016), Skopje Verticals (2017) and Endangered Species (2018). We collected abundance of material, original drawings, scans, digitized and redrawn material, archival photos, photos of the current condition of the buildings. For many buildings we made models in different sizes and material. We tried to discipline ourselves and finalize each research with a public presentation, an exhibition and a publication. Thanks to the fruitful collaboration we had over the years, most of the exhibitions took place in the premises of the Museum of the City of Skopje. We developed our own methodology, always with the idea to speak about the material, to open the question, to show the results and to raise the awareness of the public about the buildings that are our recent heritage.

Skopje Verticals, Museum of the City of Skopje (2018). | Photo © Vase Amanito

The Future as a Project: Doxiadis in Skopje, Benaki Museum, Athens (2018). | Photo © Vase Amanito

Endangered Species, Museum of Natural History (2018). | Photo © Vase Amanito

It might be interesting to point out that during the process we collaborated with many, either students of architecture in their final years of studies or just graduated young architects. These are people with great knowledge and skills, fully dedicated to the project and with great capacity for professional collaboration. Their work was completely outside the school curricula, based solely on enthusiasm and deep faith in the projects we were doing together.

How did you contributed to the exhibition “Toward a Concrete Utopia: Architecture in Yugoslavia, 1948– 1980″ in MoMA in New York?

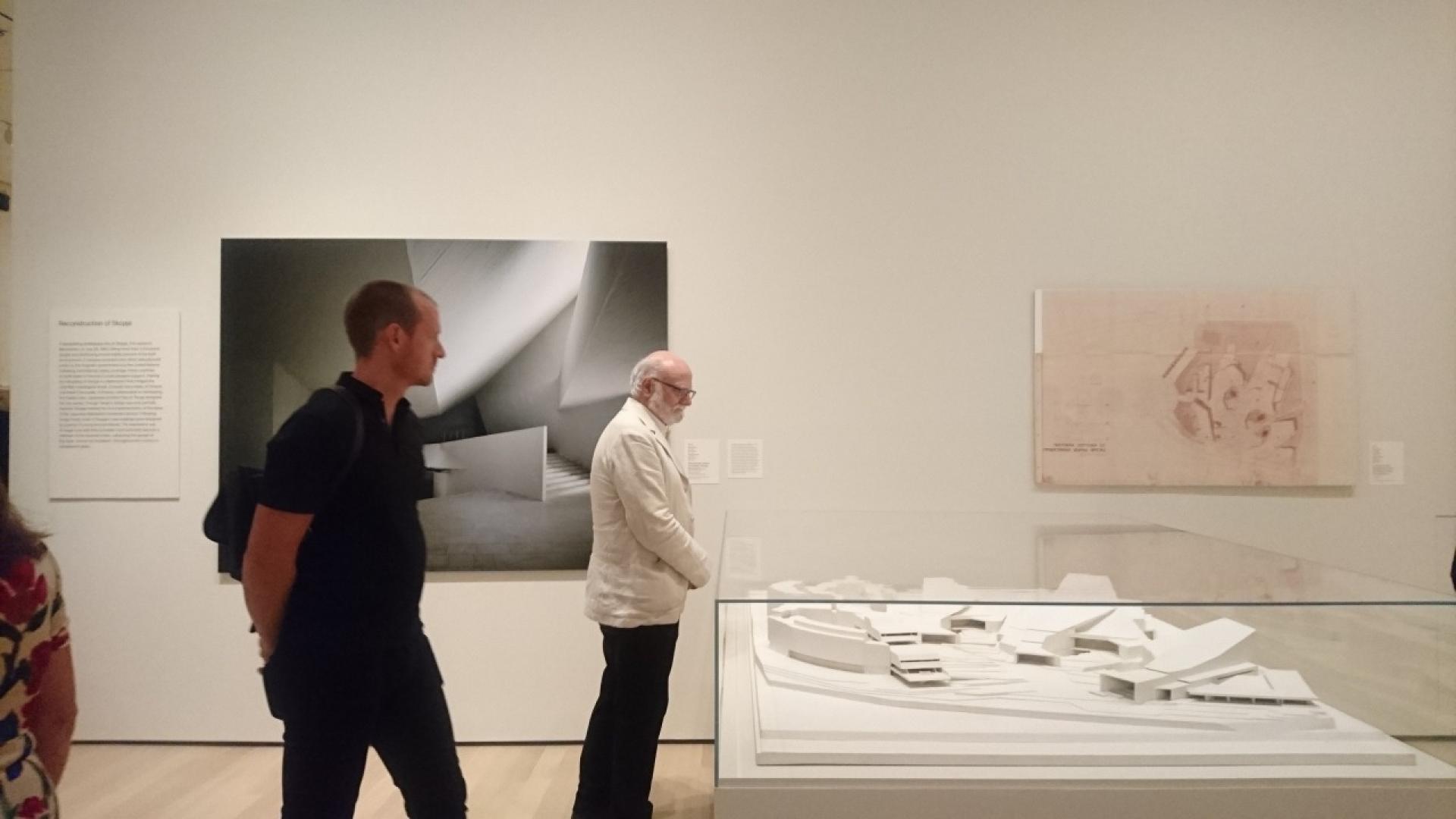

JI: For the MoMA exhibition we were invited to be part of the curatorial advisory board. At the end of 2015, the whole group met in Skopje for the first time. At that moment, it was still a bit uncertain whether the exhibition would take place. As part of the curatorial advisory board we proposed the research topic, suggested material (abundance of material that underwent several phases of selection), contacted institutions, archives, authors and their families in order to provide original material for the exhibition, contributed within the exhibition catalogue.

Toward a Concrete Utopia: Architecture in Yugoslavia, 1948–1980 at MoMA (2018). | Photo © Vladimir Deskov, Ana Ivanovska Deskova, Jovan Ivanovski

Having in mind the fact that in Macedonia 20th century architecture is still not considered a heritage, that we lack an institution dealing specifically with architecture (such as MAO in Ljubljana for example), it was quite an effort to find it and obtain permission to lend it.

What are your future plans and perspectives?

VD: As we already said, we have been researching Skopje and its modernist legacy for a decade now, presenting it in various forms (local, international exhibitions, Venice biennale) to raise local awareness and international interests about this architecture. We have collected a certain archive, created more than 30 models. Much of the work has been done almost without resources, based on our enthusiasm and the huge enthusiasm of our co-workers, former students.

City Walls | Photo © Vladimir Deskov, Ana Ivanovska Deskova, Jovan Ivanovski

The 2018 was really an overwhelming year. In May we had the finale of the project Skopje Verticals, presented in the Museum of City of Skopje, in July we traveled to New York for the opening of the exhibition we all eagerly waited for Toward a Concrete Utopia: Architecture in Yugoslavia, 1948-1980. Then in December we had the opening of Endangered Species in the Museum of Natural History in Skopje and The Future as a Project: Doxiadis in Skopje, a huge collaborative effort with our colleagues from Athens, held in Benaki Museum in Athens. One might expect that there was a loud resonance after the exhibition in MoMA; strangely so, Skopje did not give much publicity to the event. I don’t think we comprehended to the full extent the meaning of the event, that Macedonian architects and architecture were presented there; that drawings of Georgi Konstantinovski and Janko Konstantinov (for example) are now kept in the archives of MoMA.

However, we will continue working with the modernist legacy of Skopje and possibly of the wider territory of Macedonia, since we still see a huge potential for research there. There are still piles of material to be collected. We hope to get some funds that would enable us sustain with the idea.

The City Trade Center by Živko Popovski. | Photo © Damjan Momirovski

Which is your favorite part of the Skopje’s Tange plan and specific building in Skopje?

AID: Difficult question. As for Tange, probably the City Wall, as this segment of the city is functioning well even today. It introduced a large number of residents in the city center and is very active and alive; buildings themselves are creating a vast public space in between. The post-earthquake segment of Skopje is a very extraordinary collection of buildings, kind of a museum-like collection.

The Macedonian Opera and Ballet by Biro 71. | Photo © Damjan Momirovski

Inside Macedonian Opera and Ballet. | Photo © Adolph Stiller

Ana said that If she have to choose, the choice will of course be partly subjective, connecting with her memories, so it will be the National opera and ballet building, the City Trade Center and a less known but marvelous building, the High School Nikola Karev by Janko Konstantinov. As Vladimir live and grew up nearby City Trade Center, this is his favorite one.

Jovan Ivanovski (1976), Vladimir Deskov (1977) and Ana Ivanovska Deskova (1978) are architects who have been collaborating on various architectural and research projects for more than a decade. As a co-founders and members of the informal architectural group SCArS (Studio for Contemporary Architecture Skopje) participated in and won a number of awards at international and local architectural competitions. In 2014 were curators and part of the team of authors of the project Findings for the Macedonian Pavilion at the 14th Venice Biennale. They are authors of numerous research projects: “Invisible Skopje” (MGS, 2013), “Biography of an architectural work: Telecommunication Center – Skopje” (MGS 2016), “Skopje Verticals” (MGS, 2018), “Endangered Species” (Museum of Natural Sciences, 2018) and Constructing a Modernist Utopia: The Architecture of The Post-Earthquake Renewal of Skopje, 1963-1981 (Gallery MC New York, each followed by an exhibition and publication. They have presented their research on Skopje’s Modern Architecture outside the borders of Macedonia with the exhibitions “Skopje, Macedonian architecture in context” (Ringturm Gallery, Vienna, 2017), “The future as a project: Doxiadis in Skopje” (Benaki Museum, Athens, 2018) and within the wider research team at the exhibition “Toward a Concrete Utopia: Architecture in Yugoslavia 1948-1980” (MoMA, New York, 2018).