Not So Gray As It Seems

The exhibition Toward a Concrete Utopia: Architecture in Yugoslavia, 1948-1980 introduces the story how particularity and unity produced a great diversity of architectural language and expressions. The topic is presented for the very first time in the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York.

Monument to the Battle of the Sutjeska by Miodrag Živković (1965–71), Tjentište, Bosnia and Herzegovina. | Photo by © Valentin Jeck, commissioned by The Museum of Modern Art, 2016

In a conversation with one of the curators Vladimir Kulić we discover that “Yugoslavia is a kind of a reminder that architecture had wider social responsibility in transforming society and working for people beyond the wealthiest.”

Installation view of the room dedicated to Edvard Ravnikar. | Photo by © Martin Seck, commissioned by The Museum of Modern Art, 2016

Avala TV Tower by Uglješa Bogunović, Slobodan Janjić, and Milan Krstić (1960–65 (destroyed in 1999; rebuilt in 2010). Mount Avala, Belgrade, Serbia. | Photo by © Valentin Jeck, commissioned by The Museum of Modern Art, 2016

Mr. Kulić, you divided the exhibition in four parts, modernization, global networks, everyday life and identities; Can you explain why such a structure?

With this structure we tried to capture some of the defining conditions under which architecture in Yugoslavia developed. The first condition was the project of reconstruction and modernization after WWII. The transformation of cities, technologies and society was the defining framework under which entire construction of Yugoslav architecture occurred. The second condition was very specific and rather unusual geo-political situation of the county, widely connected with the rest of the world. Skopje is a great example, where a city became an architecture meeting ground for the entire world. In addition, architects from the region previously had never built anywhere outside of the region; that changed after the war as well.

Exhibition poster for the retrospective of architect Janko Konstantinov (1984). | Collage diazotype and tracing paper; Personal archive of Jovan Ivanovski

Cover of Architecture of Bosnia and the Way to Modernity by Dušan Grabrijan and Juraj Neidhardt (1957). | Collage, 14 x 14 9/16″ (36 x 37 cm). Private archive of Juraj Neidhardt

Another defining condition was a very specific texture of everyday life. Mass housing in Yugoslavia was in some ways quite unique due to a great deal of experimentation with housing typologies. The emergence of modern design and the related consumer culture added to this specific texture of everyday life, architects were fundamentally instrumental in it, because it was through them that modern design came into existence in Yugoslavia. Finally, multiculturalism of Yugoslavia was yet another defining feature. Multiple architectural cultures were developed in different parts of the country, and yet they interacted with each other and they worked under the same conditions. This kind of dynamic between particularity and unity is something that produced a great deal of diversity in terms of architectural language and expressions. Interaction between different cultures is a big issue of our current moment, so Yugoslavia is interesting case study in that respect.

National and University Library of Kosovo by Andrija Mutnjaković (1971–82); Prishtina, Kosovo. | Photo by © Valentin Jeck, commissioned by The Museum of Modern Art, 2016

Why should a US citizen really care about an exhibition about building in Yugoslavia?

I think they are two reasons. One is that this exhibition breaks a new ground for American audience as well for the audience anywhere in the West in the sense that it shows that modern architecture also flourished outside of the canonical region where we normally assume it was accepted. When you read histories of modern architecture, the geographical areas that are covered are mostly Western Europe and United States. This exhibition is a case study that demonstrates that innovative, interesting architecture was built outside of this canonical area. In particular it shows that inspired architecture existed also in what used to be the former socialist world. Yugoslavia is a great example that tells that the story is much more complicated.

Urban Planning Institute of Belgrade. Belgrade Master Plan (1949–50); Belgrade, Serbia. | Plan 1:10000. 1951. Ink and tempera on diazotype, 64 9/16 x 9 3/4″ (164 x 233 cm). Urban Planning Institute of Belgrade

Šerafudin White Mosque by Zlatko Ugljen (1969–79); Visoko, Bosnia and Herzegovina. | Photo by © Valentin Jeck, commissioned by The Museum of Modern Art, 2016

And for another?

Second reason why I think it is interesting to the American audience is the current political moment. After four decades of neoliberalism we are finally starting to see a renewed appreciation for the architecture’s role in the construction of the civic and public realm, for the communal rather than private. In the US in particular architecture has been largely reduced to kind of window dressing for the super wealthy. The amount of architectural thinking that used to be at one point distributed among the population much more widely is now concentrated in hand of the one percent. Yugoslavia in that sense is a kind of a reminder that architecture had wider social responsibility in transforming society and working for people beyond the wealthiest, beyond the one percent.

Revolution Square (today Republic Square) by Edvard Ravnikar (1960–74); Ljubljana, Slovenia. | Photo by © Valentin Jeck, commissioned by The Museum of Modern Art, 2016

Why did you choose the time frame between 1948 and 1980?

The dates are chosen both on architectural and historical criteria. We had to narrow down the topic and one of the greatest challenges was selecting and cutting down the amount of material to make the exhibition manageable. The two dates refer to two historical turning points. One is Yugoslavia’s break with Soviet Union in 1948, the other is Tito’s death in 1980. However these are also architectural turning points. After 1948 the attempted imposition of socialist realism very quickly dies off, and after 1980 we are entering in an architecture period of postmodernism.

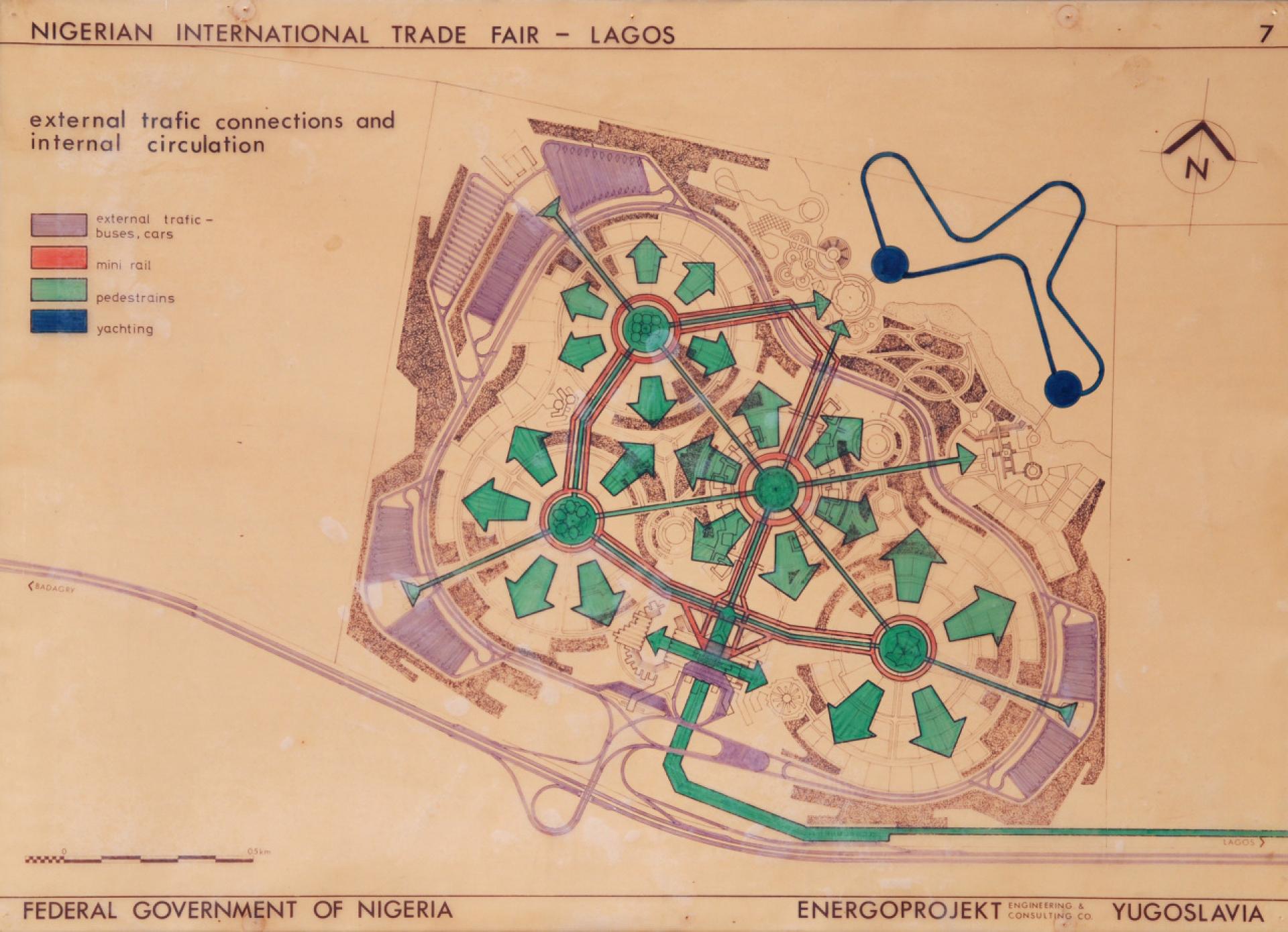

Zoran Bojović for Energoprojekt. International Trade Fair. 1973–77, Lagos, Nigeria. | Plan of external traffic connections and internal circulation, 1973. Felt tip pen on tracing paper mounted on cardboard, 27 9/16 x 39 3/8″ (70 x 100 cm). Personal archive of Zoran Bojović

The exhibition claims: Yugoslavia was an experiment?

Yugoslavia was no doubt an experiment. It went through a constant evolution. In that sense the title “Toward a concrete utopia”is appropriate. Not just in the most obvious sense, that we are talking about concrete architecture, but also in reference to Ernest Bloch’s concept of concrete utopia, which emphasizes the idea of a society in perpetual becoming, utopia as a process in constant transformation. Yugoslavia was in that sense indeed a utopia because it was in constant search of improvement. The exhibition argues that much of the architecture produced in Yugoslavia was quite experimental. The question is whether the experiment failed.

And?

In the most developed capitalist countries the modernization and urbanization occurred through extreme sacrifices from the working class. We could speculate that the price of modernization in Yugoslavia was more justly distributed. Yugoslavia’s failure was ultimately to reproduce its own system, which something that capitalism achieves successfully, despite the constant cycles of crises.

S2 Office Tower by Milan Mihelič (1972–78); Ljubljana, Slovenia. | Photo by © Valentin Jeck, commissioned by The Museum of Modern Art, 2016

Besides modernism and brutalism, structuralism, metabolism and postmodernism were also dominant in Yugoslavia. How does the exhibition convey this very elaborate architectural vocabulary?

One of the ways in which we tried to convey this diversity is through four monographic rooms dedicated to individual architects, who were among the most prominent professional figures. They are Vjenceslav Richter, Edvard Ravnikar, Juraj Neidhardt and Bogdan Bogdanović. Their wildly divergent personal oeuvres illustrate the extreme diversity of architectural approaches, methods, expressions and languages cultivated in Yugoslavia. Richter was at the core of the neoavant-garde movement of the 1950s and 1960s. Bogdanović was the product of the surrealist movement dating back to the 1920s and 1930s. Neidhart was perhaps the most interesting figure of critical regionalism, whereas Ravnikar, was a great synthesizer of architectural ideas, from Plečnik, to Le Corbusier and Aalto. Despite their differences, all four of these architects contributed to the construction of the most politically significant structures in the country, from parliament buildings and exhibition pavilions, to World War II monuments. That kind of diversity of representational languages was rare elsewhere.

Yugoslav Pavilion at Expo 58 by Vjenceslav Richter (1958); Brussels, Belgium. | Photo by Archive of Yugoslavia

All four are men…

One of my favorite exhibits in the show is the photo of Milica Šterić sitting in an office in Energoprojekt headquarters in Belgrade with clients from Africa. Surrounded by standing white men who listen to them. This image tells about this subversion of traditional race and gender hierarchies, demonstrating the truly utopian dimension of Yugoslavia, which attempted to liberate and empower all kinds of groups that were disfranchised throughout history, including women.

Milica Šterić at the meeting in Energoprojekt. | Photo via ZUA

Just like Milica Šterić?

Milica Šterić was significant as an architect but even more importantly as an architectural manager, who was able to successfully negotiate contracts throughout Africa and the Middle East. Another well-connected woman was Svetlana Radević, who was awarded the national prize for architecture in the 1960s. After that she studied with Louis Kahn, worked with Kisho Kurokawa, spend time in Switzerland and Japan and was able to produce a great deal of interesting advanced architecture. I don’t want to say that Yugoslavia was some kind of feminist paradise because women were still the minority in the architectural and they had a hard time breaking the glass ceiling, but deliberate efforts at their inclusion where nevertheless made.

How was housing developed in Yugoslavia comparing to other Eastern European countries?

A short answer would be mass housing in Yugoslavia was also rather diverse. After WWII, not just in Eastern Europe but in Western Europe as well, standardization, typification and industrialization of housing were the orders of the day because huge numbers of people were left homeless. In some East European countries like the GDR and Czechoslovakia standardization and typification were extremely successful. The Soviet Union produced what we could be termed the largest architectural modernization project in the world with 30 million apartments, again based on standardized designs.

And in Yugoslavia?

In Yugoslavia that never happened, in part due to the early decentralization. In some ways, it was a failure of the postwar ideal of mass industrial construction, but the side effect was the avoidance of the kind of urban monotony known in some other parts of Europe.

Braće Borozan building block in Split 3 by Dinko Kovačić and Mihajlo Zorić (1970–79); Split, Croatia. | Photo by © Valentin Jeck, commissioned by The Museum of Modern Art, 2016

Apartment Building on Laginjina Street by Ivan Vitić (1957–62); Zagreb, Croatia. | Perspective drawing, 1960. Tempera, pencil, and ink on paper, 27 15/16 × 39 3/8″ (71 × 100 cm). Ivan Vitić Archive, Croatian Academy of Sciences and Arts

Is it possible to distinguish housing from tourism architecture, which at the same time hat great success?

Tourism architecture was one of the success stories in Yugoslavia. By the time mass tourism started exploding on the Adriatic in the early 1960s there were already some experiences with the development of the mass tourism elsewhere on the Mediterranean, which raised an awareness of the danger of uncoordinated, chaotic development. This awareness was built into the DNA of tourism architecture. There were great efforts to accommodate hundreds of thousands of tourist that were coming to the Adriatic and the same time preserve the quality of the natural environment and the historical cities. Architects developed numerous strategies for preserving the environment, carefully incorporating new architecture into the natural landscape. The body of architecture inherited from 1960s and 1970s is still instructive, carrying with itself a great deal of cultural capital that survives to this day.

Installation view of Toward a Concrete Utopia: Architecture in Yugoslavia, 1948–1980, The Museum of Modern Art, New York, July 15, 2018–January 13, 2019. | Photo by © Martin Beck, The Museum of Modern Art, 2018

Monument to the Ilinden Uprising by Jordan and Iskra Grabul (1970–73); Kruševo, Macedonia. | Photo by © Valentin Jeck, commissioned by The Museum of Modern Art, 2016

What role play monuments as part of this architectural exhibition?

The monuments conclude the exhibition. They speak of an important architectural typology produced in postwar Yugoslavia, but in a way, they commemorate Yugoslavia itself. Some of the most important ones are badly damage, and their current shape serves as a reminder of the destruction of Yugoslavia. At the exit from the gallery a mural by David Maljković poses an important question: What do these derelict antifascist monuments mean for us today? It is a very important question in this current political climate. The exhibition ends with a question and a warning.

Monument to the Uprising of the People of Kordun and Banija by Berislav Šerbetić and Vojin Bakić (1979–81); Petrova Gora, Croatia. | Photo by © Valentin Jeck, commissioned by The Museum of Modern Art, 2016

Vladimir Kulić is an architectural historian, curator, and critic specializing in modern and contemporary architecture. He is Associate Professor at Florida Atlantic University, where he teaches courses in architectural history, theory, and design. Kulić has written extensively about architecture in the former Yugoslavia. His first book, Modernism In-Between: The Mediatory Architectures of Socialist Yugoslavia (with Maroje Mrduljaš, photos by Wolfgang Thaler, 2012), surveyed the remarkable body of architecture produced in that country after World War II. He has received numerous fellowships, grants, and awards, including those from the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, the American Academy in Berlin, the Graham Foundation, the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC, the American Council of Learned Societies, and the Fondazione Bruno Zevi in Rome. | Photo by © Annette Hornischer