Pioneer Architects X

Marianne Várnay’s words for the newsmagazine Ujsag on 20 October 1929 after she visited Corbusier in Paris: „the famed architect turned me away on my visit with an irrefutable, lovely, truly French compliment: if I want to make money despite being a woman, why not looking for a female job, and insisting on a male one? Good old French gallants! I just laughed and kept on going.”

Várnay’s Anna spring house in Szeged around 1935. | Photo from Kovac Archive

Várnay was the first female architect to graduate on the Budapest University of Technology in 1924, and had therefore a rough but surprisingly fast route to success. She had not only graduated, but also been accepted as a member of the Association of Hungarian Engineers and Architects and visited Le Corbusier in Paris. She had worked in offices of Josef Gočár and Kamil Roškot in Prague and at the same time won a competition in Wiener Neustadt under a friend’s name and changed her family name from Sternberg to Várnay as a sign of respect towards her mother, Ilona.

Marianne Várnay, 1938 | Photo published in Az Est

It is a certain fact though, that year 1929 brought Várnay her first success in Hungary. She got an award on the master plan competition of Győr. It took almost another decade to actually build something. Only after another won competition in 1937 Várnay finished her first edifice, an art deco corner building in her home town of Szeged, built for the State Social Security Institute, known by its abbreviation OTI. An article in the 16 February 1938 editition of the daily Az Est mentions another first prize she won in 1938, and was about to design a new concert hall in Szeged. Being born into a Jewish family, she soon lost her hard-earned license to practice as an architect and she disappears.

Várnay’s OTI building in Szeged. | Photo via atomboy, Wikimedia Commons

While Várnay was the first woman with an architecture degree in Budapest, she was certainly not the first one to design and construct a building in Hungary. During the early 20th Century, when architecture profession and building construction practice was not strictly separated, there were several women who managed to build up a reputation. They appeared in newspaper articles as strange curiosities like for example Erika Paulas, Szerén Erdélyi, Ilona Préda.

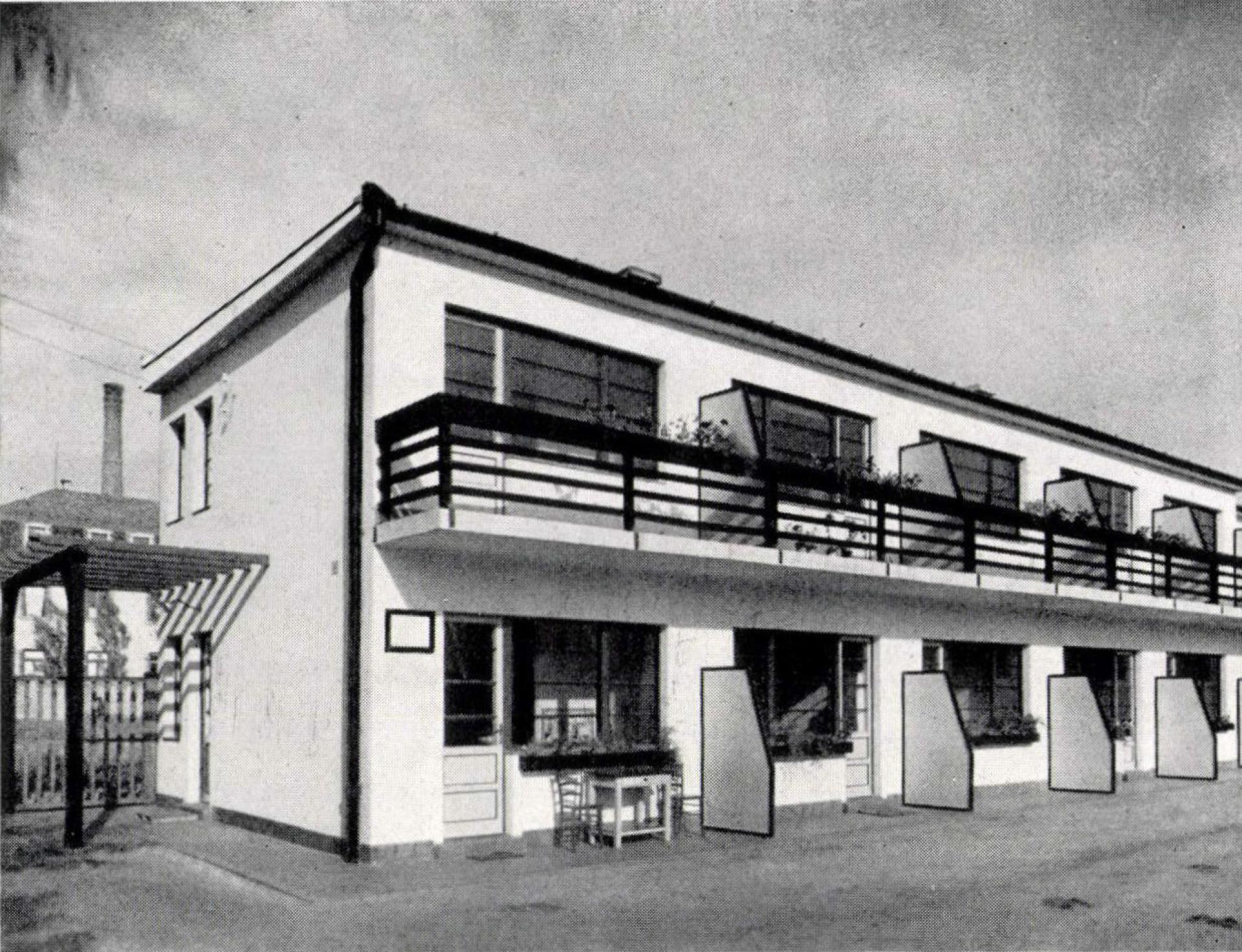

Old worker’s home in Újpest; the original state. | Photo unknown author, 1936

Franciska Bettelheim’s first work was constructed a year before Várnay’s achievement. While Bettelheim, daughter of a well-to-do factory owner from Újpest, graduated a decade after Várnay. With the help of her family’s position and money she managed to realize her first building in 1936. Her modernist block in Újpest was designed for retired workers of the family’s factory. During the past 80 years the house had lost some of its charm, but it maintained the overall structure and even some of the original details.

Old worker’s home current state. | Photo by Dániel Kovács

Her vision of a responsible society was in line with progressive architecture thinking of the time, what is documented in the building’s presentation in Hungary’s foremost modernist architecture magazine Tér és Forma. Also her next commission, the Bettelheim family villa from 1938 got the same attention. In 1935 she moved to Switzerland with her husband, university professor László Lédermann, and her homeland carrier ended.

The shortness of women’s carriers in architecture are very common in the strict right-wing climate of the interwar years’ kingless Hungarian Kingdom, where was not easy for a woman to excel in professions usually occupied by man. The war, and more precisely the forthcoming years of Communist dictatorship, brought a surprising change in this aspect.

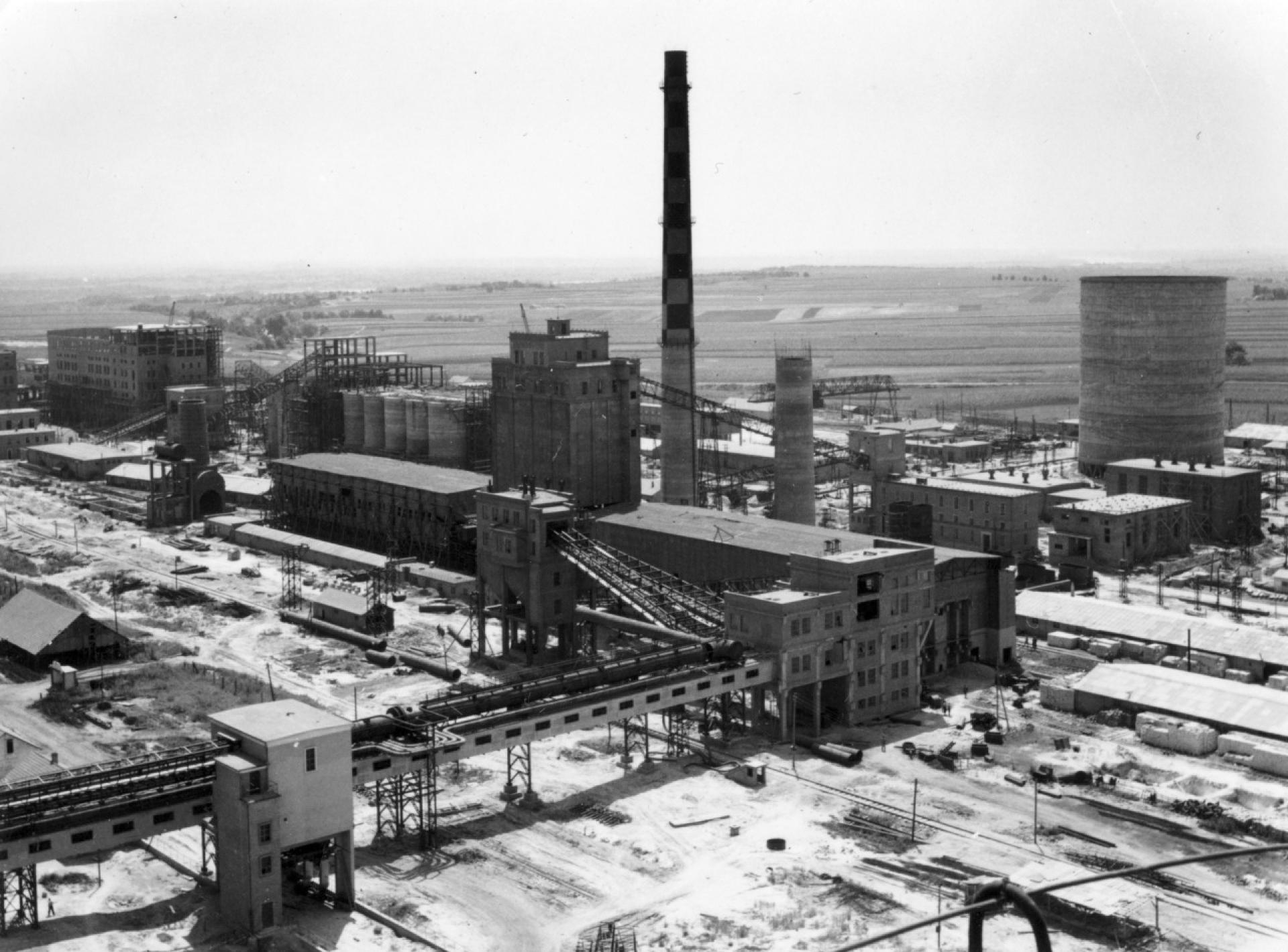

Sztálinváros Iron Works. | Photo via Fortepan, orig. Gallai Sándor

Johanna Wolf, who was reportedly ostracized by her university classmates in the 1920s for her Jewish origins, became a poster woman for the new society from the 1950s. This happened because of her early decision not to pursue a carrier as an independent architect, but to join a group specialized on pre-cast concrete construction in the late 1930s.

During the forced industrialization of the early 1950s, most professionals of the group received high positions and Wolf herself became the chief engineer at the Sztálinváros Iron Works building site. Being a female and responsible for the country’s biggest industrial project in a newly founded city named after the ultimate Communist leader, meant big responsibility and visibility. She frequently appeared in newspapers saying “The boom of our construction industry secures new tasks, but also new honors to the polytechnic academics.” Wolf managed to keep her newly found popularity well after the political changes brought by Stalin’s death and the 1956 revolution. She retired as chief engineer of the State Construction Company of Chemical Plants. Unlike her former male engineer colleagues like Gyula Mátray or László Mokk, she never received the most important state honors such as the Kossuth Prize or the Ybl Miklós Prize.

Mináry’s apartment building from 1957. | Photo by Dániel Kovács

The first woman to get the state architecture award Miklós Ybl in 1964 was Olga Mináry. That was 11 years after its foundation. Mináry’s award can be seen as highly symbolic, as a 1951 graduate, she didn’t have any undesirable pre-war associations, and she was also among the first to turn her back to Socialist Realism and swing around to modernist ideals after 1956. Her apartment building in Frankel Leó utca, co-designed with István Janáky Sr. and Dénes Perczel, is one of the first modernist buildings in Budapest. In 1958 she won the National apartment building competition and her work was realized as part of the experimental housing project in Óbuda (Budapest III).

Mináry’s Alutröszt Headquarters in its original form. | Photo via Fortepan, orig. Angyalföldi Helytörténeti Gyűjtemény

The project, a fresh initiative to resolve the country’s housing shortage (later, sadly, settled with thousands of prefabricated industrial blocks), shortlisted Hungary’s most progressive minds and brought great success to most. It was actually Mináry’s plan and her Model Building No. 527 that got her the Ybl Prize in 1964. Two years later she realized her biggest project the new headquarters for the State Aluminum Trust. The shiny aluminium-covered office block is standing on a picturesque riverside location and belongs to the foremost examples of late modern architecture in Hungary.

Wounds and offences suffered in a male-dominated profession embittered and dispirited Mináry to her last years. But she has been an important fighter of female emancipation, and without her, we probably couldn’t mention Margit Pázmándi’s as the only Hungarian woman to receive the Ybl Prize twice.

Margit Pázmándi. | Photo via epiteszforum.hu

While being a widely respected and influential figure of her times, Pázmándi’s eminent role was at least in part thanks to her marriage to a similarly vigorous and pioneering architect Csaba Virág. Especially in the 1960s and 1970s, Pázmándi and Virág participated and won several competitions, the reconstruction of the Renaissance palace of King Matthias in Visegrád, or the new headquarters of the Hungarian National Television.

Central Command of the Workers’ Militia, 1985. | Photo by Dániel Kovács

Despite their personal and professional relationship, she managed to build up an independent carrier with numerous private and public commissions. She received her first award for a hotel in Balatonfüred, erected in the fever of mass tourism developments of the 60s. In 1986 she got the award for her lifetime achievements, just after finishing her last and probably biggest project, the new headquarters for the Worker’s Militia in Buda. Pázmándi was not known to say no. “I don’t believe woman could not do any kind of work, in proper context and environs,”she said after taking over the second Ybl Prize. “I have been lucky in this regard. (…) I never felt any drawback of being a woman in this profession, because I managed to fight respect out. I was though and stubborn enough, if I needed to.”

—

by Dániel Kovács