FOMA 11: The Luxury Of Sharing

The eleventh FOMA is discovering the 1980′s Santiago de Chile with José Tomás Pérez Valle. We will learn how Fernando Castillo Velasco’s studio production focused on the housing problem with a counterintuitive model where sharing was not necessary a duty but a luxury.

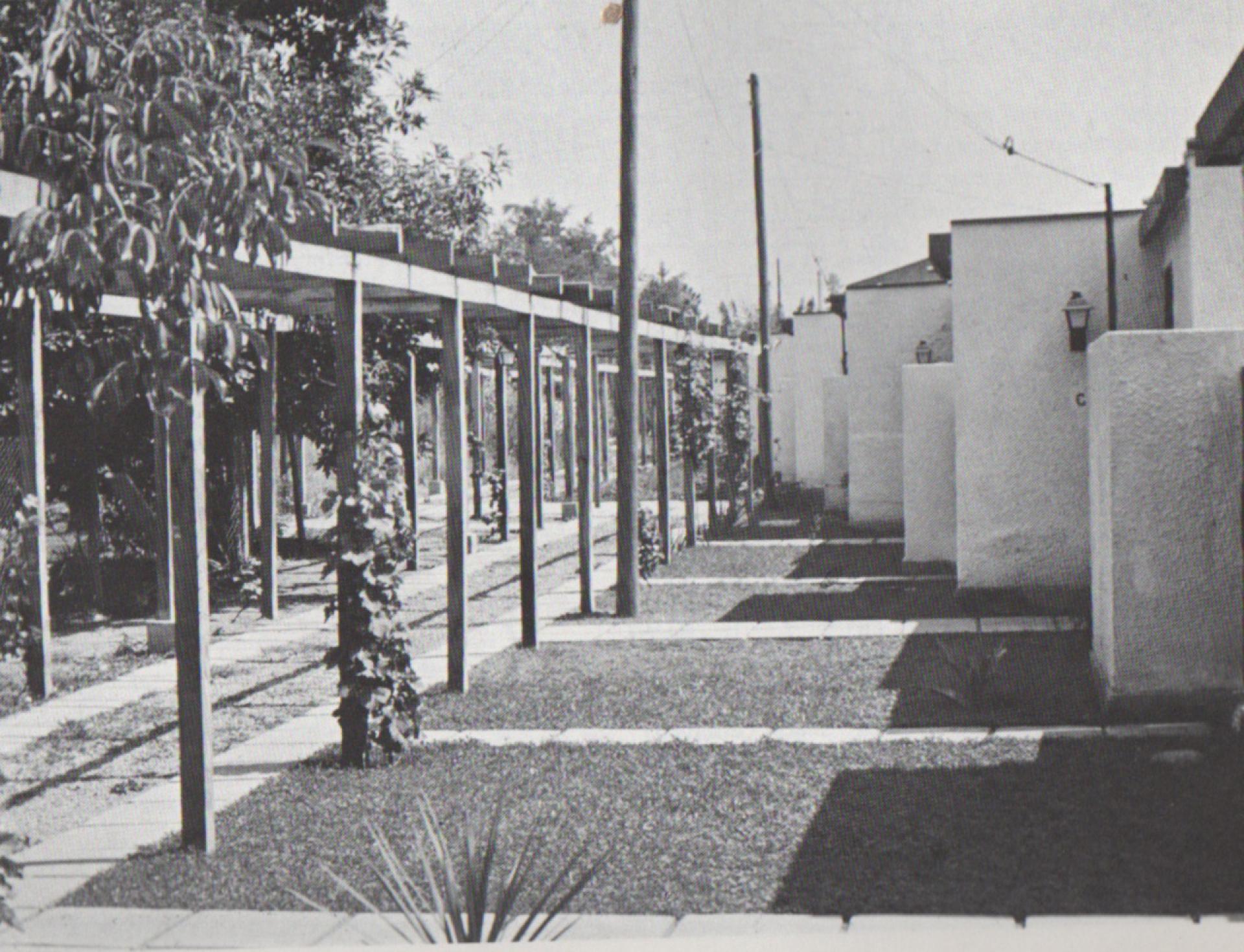

Quinta Michita was with a group of 25 one floor dwellings the first primitive model for the communities during the 80’s. | Photo by Humberto Eliash

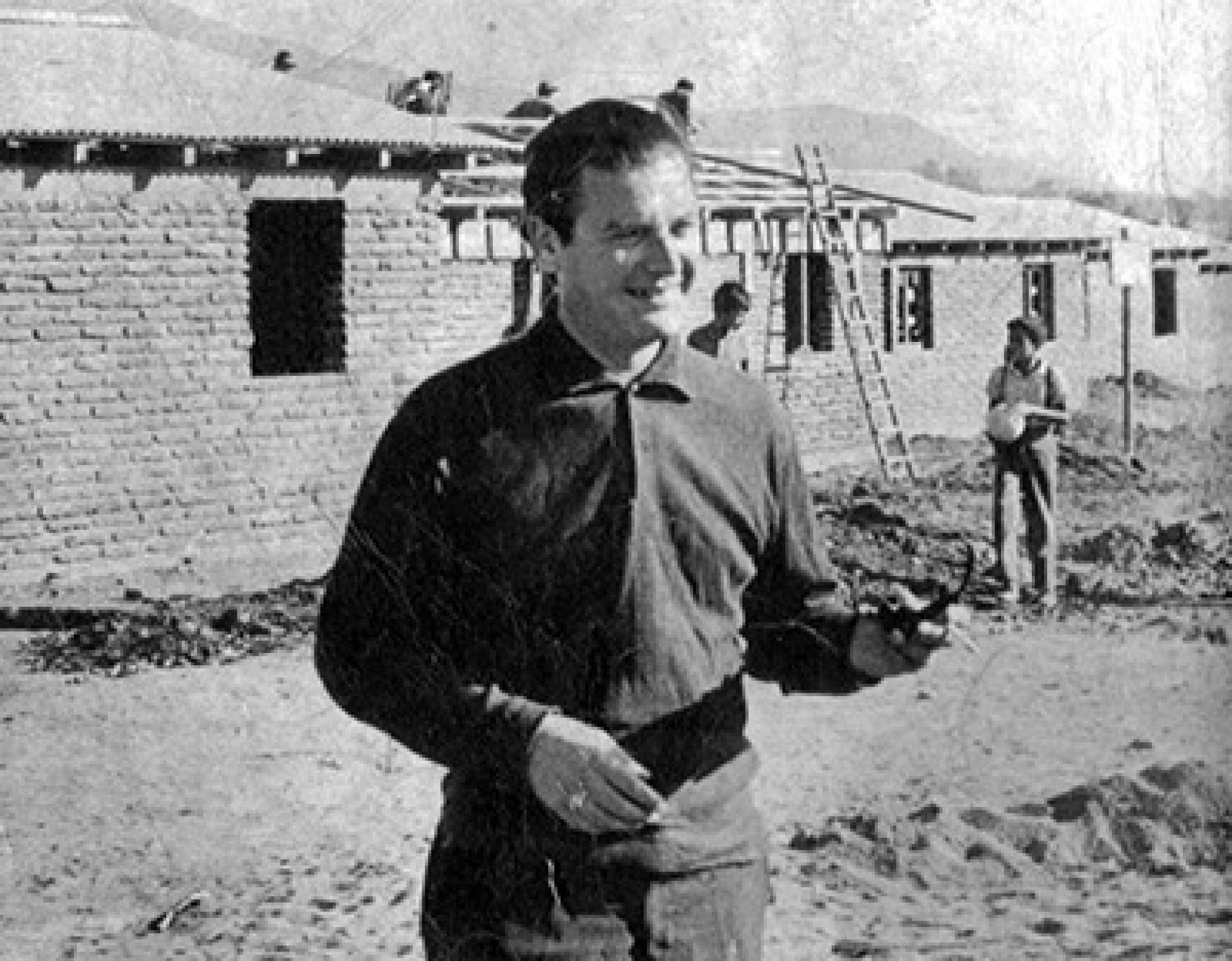

Castillo Velasco came back from exile with a prohibition by the dictatorship to be part of any political activity - centres the attention of his professional studio on alternative ways of ownership. In contrast to the neoliberal housing policies implemented in Chile [1].

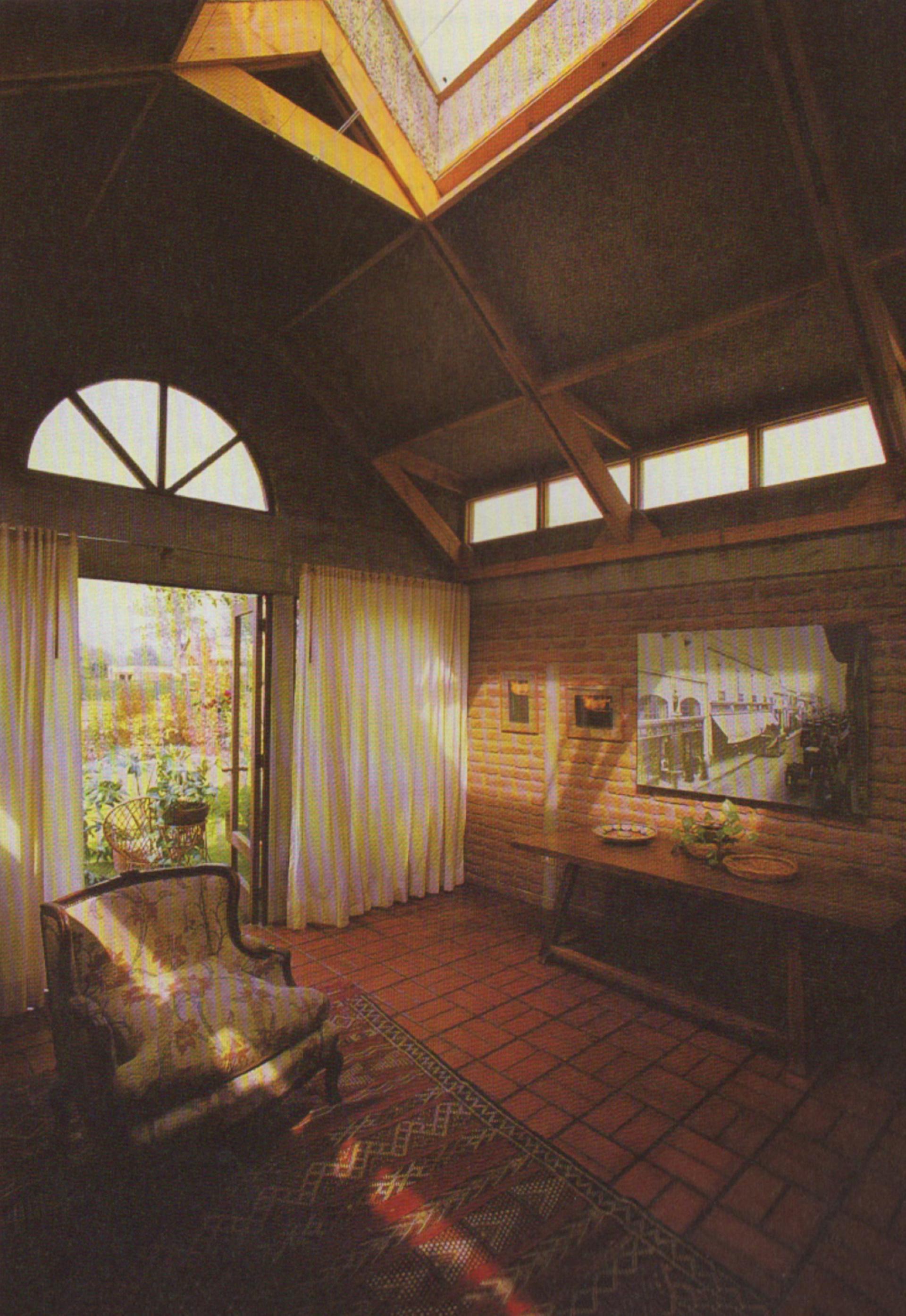

Quinta Michita interior emphasis was placed on the overall impression of the complex, rather than the individuality of each dwelling, and this effect has increased over time with the growth of vegetation. | Photo by Luis Poirot

Las Comunidades are a group of few dozens housing complex, with groups of 4 to 30 houses, built between 1981 and 1992, and located mainly in La Reina; an almost rural upper middle-class suburb on east Santiago in Chile. A distinct condition of these houses is not necessary the appearances as a physical object but the exceptional guidelines that oriented the architectural decisions. These strategies are “the collective organization of a piece of land, the minimization of private space consequently the maximization of collective spaces and the respect of the environment.” [2]

Common areas of Las Alamedas (1984). | Photo by Humberto Eliash

From the outside, the houses are unmarkable, almost hidden between nature. These complexes contemplates an austere exterior: brutalist structures that use reinforced concrete and artisanal open-faced bricks. Also, the architects considered the use of demolition materials and even the appropriation of some existing structures. This frugality on the material decision was an open critic against the technological extravagances [3] of the 80’s buildings of the so-called Chilean Economic Miracle.

Interior at Comunidad Las Alamedas (1984). | Photo by Luis Poirot

The distribution plan always shows the tension between the possibilities of common spaces and the minimization of the private. The selection of attached-houses distribution provides a barrier to separate common areas from the parking lot or the streets. In most cases, these flexible use of the site, allows the architects to preserve part of the previous natural attributes and reduce the parking lots presence. In the architect’s words “The creation of an oasis in the desert of the modern city”. [4]

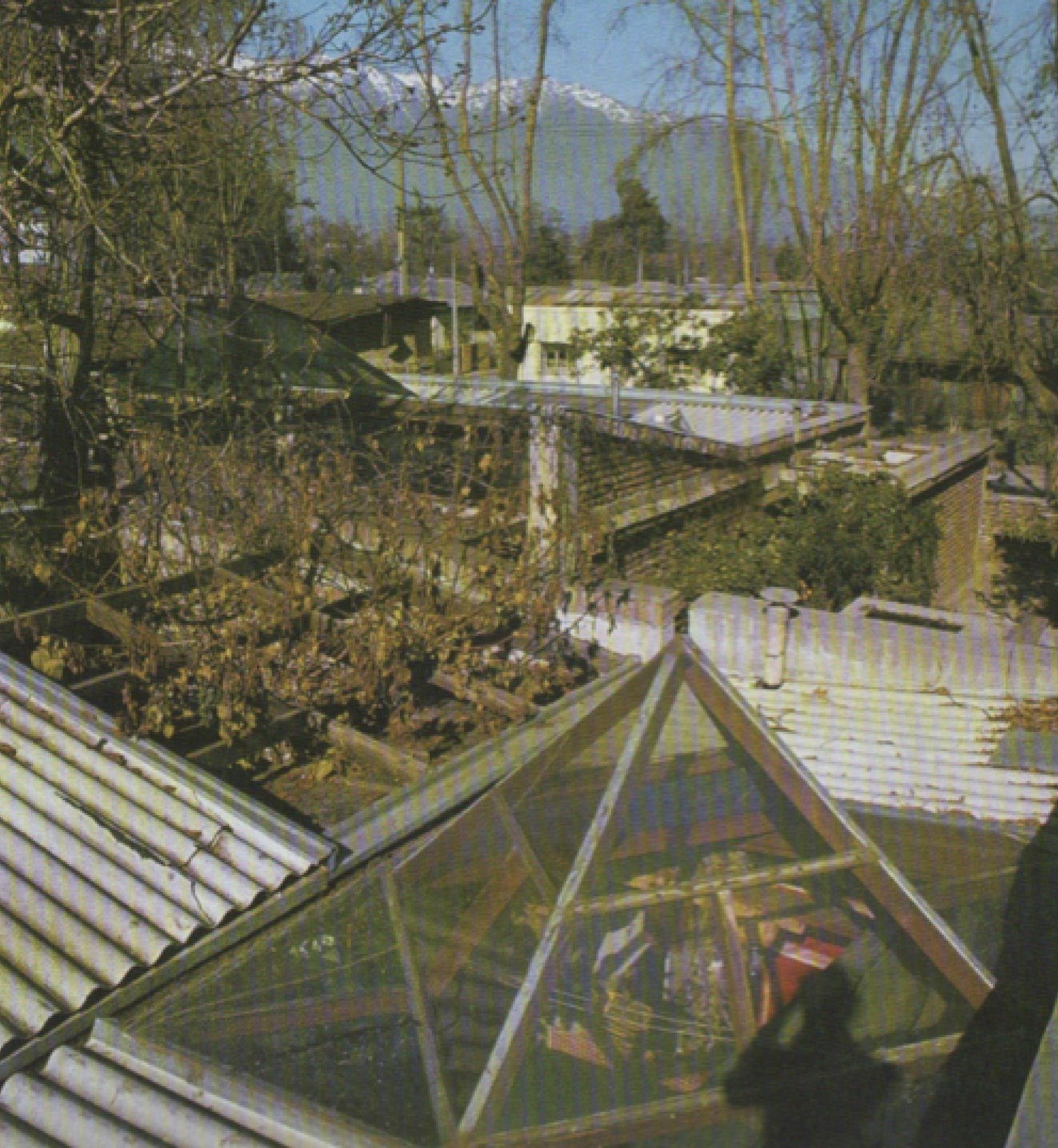

Much has been said about the work of the skylight and lucarnas, however, something almost is forgotten: the introduction of a central enclosed space without a roof: a garden room. As a consequence of the distribution, this room allows to bring sun-lights to the interior but also introduces the idea of a core: a privileged place where not only the light is shared but a place where the different user’s daily paths encounter each other.

Central enclosed space at Comunidad El Canelo (1986). | Photo by José Pérez

The financial scheme was very rare at that time. As an attempt to bypass the big Real-Estates inversion clusters the chosen strategy was a joint purchased agreement, similar to a crowdfunding. This allows a better separation of architectural decision from the market rules. Also, it makes possible the reduction of some speculation between production cost and selling price. Making long story short, the users constitute a society that makes the purchase, they pay directly; the land price, the construction and management cost. Commenting on the financial strategy, architect Fernando Castillo Velasco described “It was not difficult to find 15 families who were ready to share in the task of buying a plot of land, to agree on its objectives and mutually resolve the difficulties which arose. These community works are the counterpart of the frenetic race for building more and more without any other reason that of the financial speculation”.[5]

Fernando Castillo Velasco during housing construction. | Photo via Wikimedia

In fact, the initial price of these houses was less expensive than other market alternatives. Paradoxically more than 20 years later, these relax attitude against the housing market derives on an opposite result: houses have had a sustained progression at prices better than the other average market options, indeed, a 20 or 30 % higher than housing complex developed by conventional Real-Estate initiatives at that time. Without an explicit intention, and similarly to punk or rap, this intuitive decision to use certain material attitude challenging the establishment in long terms became fashionable.

Exterior view at Comunidad Vicente Pérez Rosales (1981). | Photo by José Pérez

The dictatorship was over, the dismissal of this housing model has a lot to do with the impossibility to be fast enough to compete against conventional Real-Estate initiatives. Also, it’s true that this project was never massive, it operated as an exception oriented towards a particular cultural milieu. However, these houses were a significant possibility to reframe new ways of sharing in a Chilean society where the notion of community was perceived with suspicion.

Entre Medianeros housing, La Reina in 1978. | Photo by Eliash Humberto

Today, hidden between nature and surrounded by construction sites, new supermarkets and strip malls with Starbucks, these plots and houses constitute an archipelago of enclaves: exceptional spaces of resistance against the Sprawl of Santiago. Even if the future is not bright, these dwellings are still there challenging the contemporary urbanization: keeping on the initial idea of Castillo to explore a counter-narrative that resists not only trough time but also creates a defiant oasis inside the neoliberal city. [6]

Real-Estate housing in La Reina, Santiago today. | Photo via Portalinmobiliario

Notes

[1] Contemporary to the Thatcher housing policies; as “Right to Buy”, Pinochet administration introduces a scheme for removal of informal collective land occupancies in wealthy areas of Santiago to relocated them towards the peripheries, with the promise to own-your-house: a titled of a dominion of a tiny houses or apartment. Not officially and almost ironically known as El sueño de la casa propia (The dream to own a house). These policies over the years amplified one of the biggest burdens of the Chilean’s cities: the inequality of access and segregation.

[2] see Eliash Humberto, “De lo Moderno a lo Real” (Colecciones SomosSur, Bogotá, Colombia, 1990) pg. 105.

[3] ibid.

[4] see Fernando Castillo Velasco, Part of the Master Class: National Prize for Architecture. Chile 1983. In Eliash Humberto, “De lo Moderno a lo Real” (Colecciones SomosSur, Bogotá, Colombia, 1990), pg. 227.

[5] ibid.

[6] see Fernando Castillo Velasco, Part of the Master Class: National Prize for Architecture. Chile 1983. In Eliash Humberto, “De lo Moderno a lo Real” (Colecciones SomosSur, Bogotá, Colombia,1990), pg. 227.

José Tomás Pérez Valle (1990) is an architect born in Santiago de Chile. Through his design practice and theoretical research, he operates at the intersection between form firmly rooted in architectural theory and socio-economic power relationship in space. José’s written and un-built work has been published in Revista ARQ and Archifutures, and has been exhibited at the Haus der Architektur in Graz, Museum of Architecture and Design in Ljubljana, China Academy of Fine Arts in Beijing. He is a co-founder of Radio Arcada, a video/ editorial initiative, supported by Extensión Escuela de Arquitectura Universidad Católica. José holds a professional degree of Architecture from the Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile (2016) also undergraduate studies at The Oslo School of Architecture and Design in Norway (2014).