Everything Could Always Be Different: Women of IBA 1984/87

The International Building Exhibition 1984/87 was an architectural exhibition and an urban planning concept adopted by the Senate of Berlin in 1979, to rebuild and redevelop the residential blocks of West Berlin city center. It consisted of two parts: new urban construction – IBA Neubau, led by Josef Paul Kleihues, and urban renewal – IBA Altbau, led by Hardt-Waltherr Hämer. The exhibition aimed to solve the specific urban problems of the inner-city blocks through a careful, cooperative and participatory approach that should engage all social groups. Women were sidelined in this process, as architects and planners and as members of target communities. However, they demanded a seat at the IBA table – and made a lasting difference.

A Female reportage photographer surveys Berlin (c. 1910) | Photo via German History in Documents and Images

The issue of women’s participation in IBA arose at the beginning of the 1980s. Numerous experts were invited by IBA to a public hearing, where they shared their opinion on various social issues relevant to designing the urban renewal process. None of these experts were women. Women from a feminist group Frau-Steine-Erde – architects, engineers, scientists – did, however, attend the hearing, and interrupted it to voice their concern over the exclusion of women from the planning and construction process. They made seven unannounced speeches at the hearing, in which they criticized IBA not only for not engaging female experts and commissioning only male architects but also for not taking into account the way in which the renewal project will affect female residents, who usually bear the burden of the big changes in their communities. They insisted on women’s participation in all stages of the planning process, with consideration for the living conditions of women during the renewals. They also requested for female architects and planners to be hired by IBA. This intervention resulted in certain concessions, which led to more opportunities for female designers and architects to get involved in the program – albeit with delay. It also resulted in the creation of FOPA/ Feminist Organization of Planners and Architects. The first meeting of FOPA was held on December 20, 1981 in Berlin and regional groups were later formed in other German cities. The organization is still active and still working to promote feminist positions in architecture, planning, environmental and building policy.

Feminist Organization of Planners and Architects: Board of Directors | Photo via FOPA

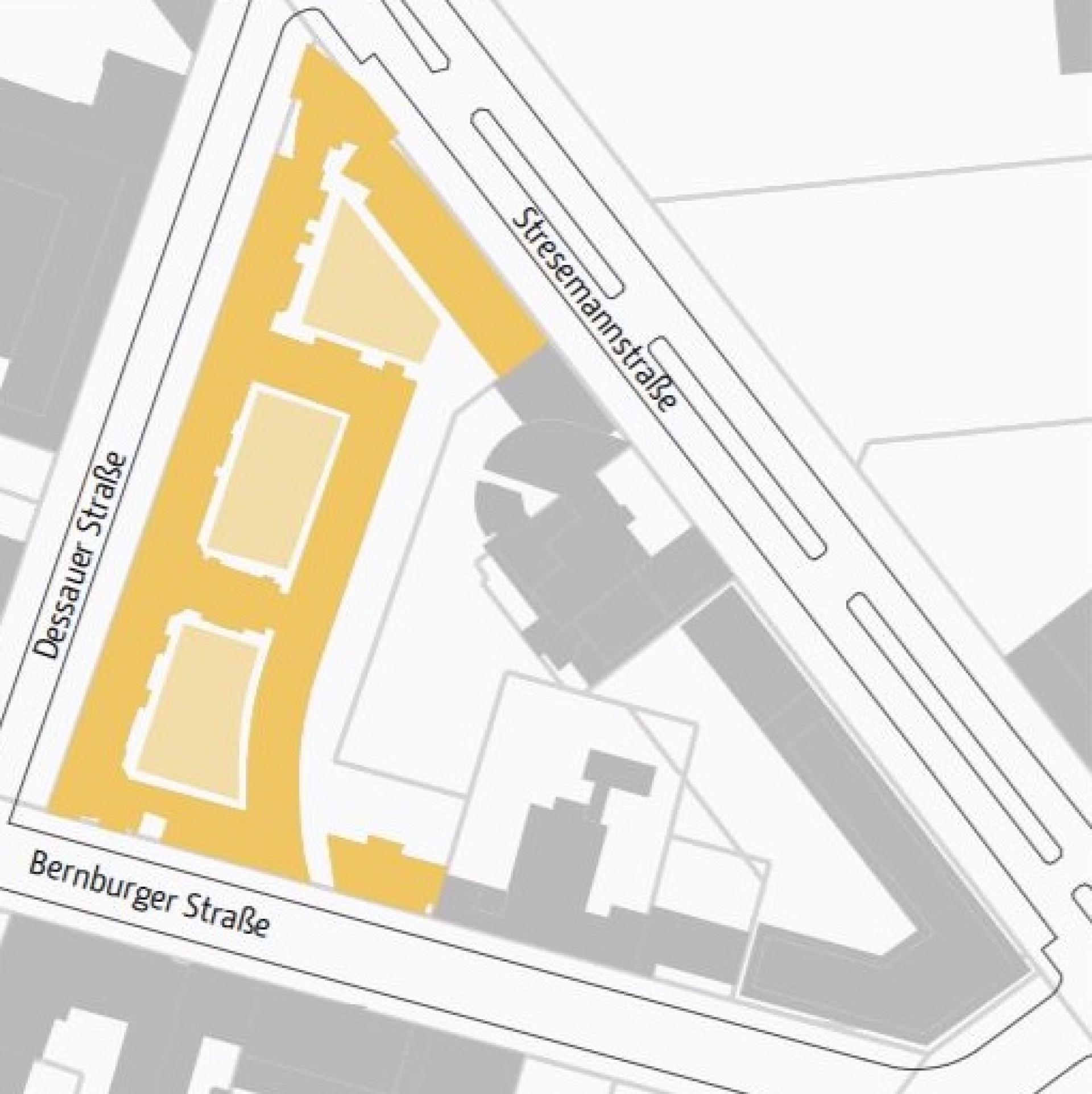

The initiative to involve women as authors has ultimately led to a decision to invite several female architects, local and international, to participate in the reconstruction of Block 2 where a project for an emancipatory living was to be developed. Situated between Stresemannstrasse, Dessauerstrasse and Bernburger Strasse, at the time of planning this block was a stone’s throw away from the Berlin Wall. It was divided into six lots, three of which – lots 1, 2 and 3 – were designated for women’s architectural projects, which were supposed to respond to specific demands of women living in the city. IBA hired Zaha Hadid (Baghdad / London), Myra Warhaftig, (Tel Aviv / Berlin) and Christine Jachmann (Berlin), who was also in charge of coordinating the planning process for the entire block.

IBA Block 2: Situation | Illustration via Marianna Poppitz

The project was challenging, and challenged on several points, such as the mere definition of emancipatory living and the constraints imposed by the idea of what social housing is and could be. Young Zaha Hadid found the theme of women building for women limiting and responded with an expressively designed tower, seeking freedom through the form in the walled-off city. She left the project before the completion, but her Degewo Residential Building was finished – it still excites architecture students and connoisseurs as a lesser-known Berlin work of the famous architect.

Degewo Residential Building by Zaha Hadid | Photo via ReVision - IBA 1987 exhibition catalog

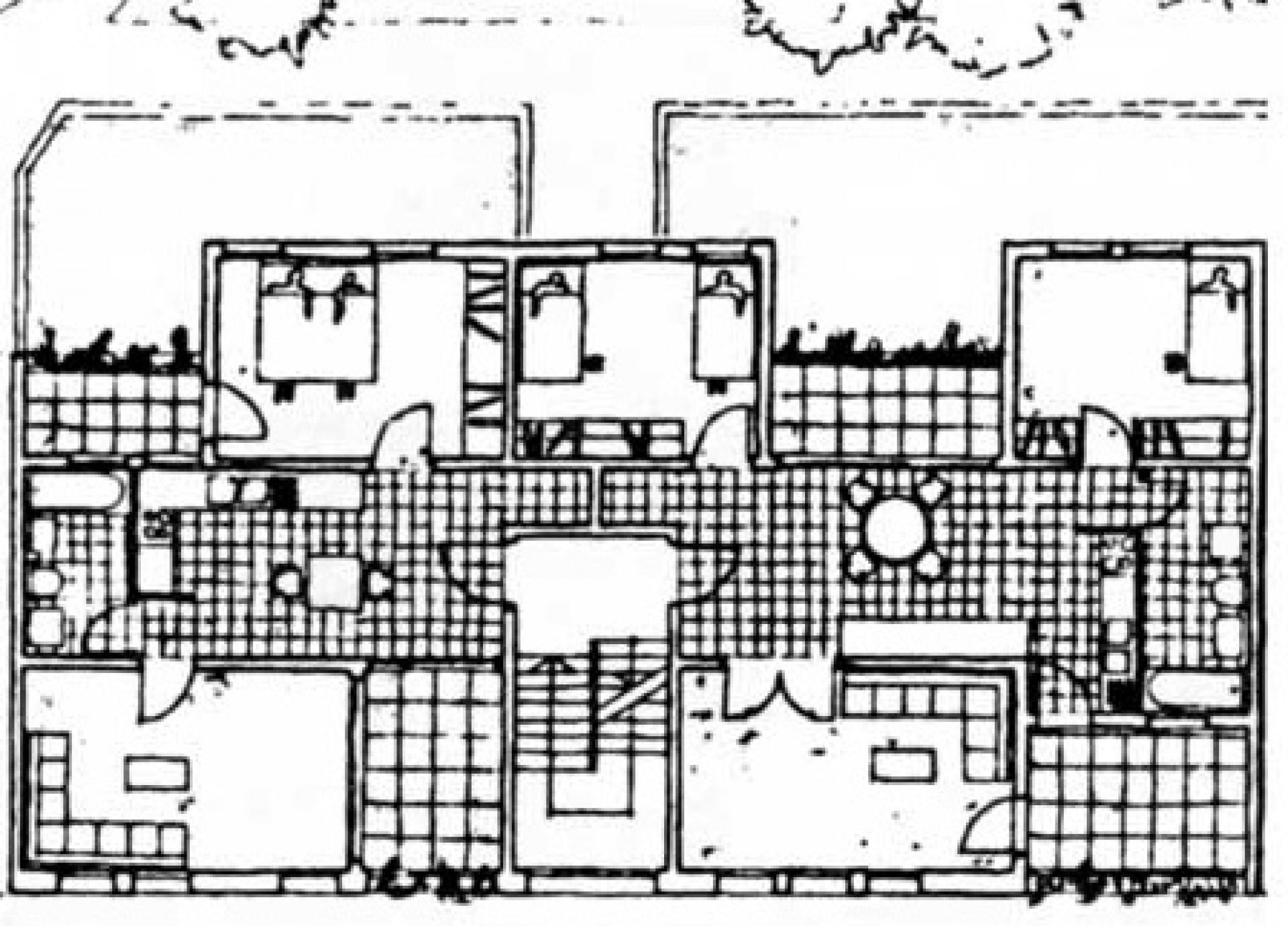

Myra Warhaftig used this opportunity to put some of her ideas about the connection between housing and women’s emancipation into practice. In 1978, she did a thesis on how the contemporary forms of dwelling contribute to confining women to solitary spaces and duties of homemaking. In Block 2 she built a house of 24 units, each of them equipped with big, central communication spaces where the activities traditionally perceived as women’s work – cooking, childcare – could be combined and shared with other household members. Once the house was built, Warhaftig moved into one of the apartments with her two children. She wanted to personally experience how this space, which she created with the emancipation of women in mind, fits woman’s needs. She lived there for the rest of her life. In 2011, a memorial plaque in her honor was unveiled. It reads: “Here, from 1993 to 2008, lived Myra Warhaftig (11.3.1930 - 4.3.2008), architect and architecture historian. This house was designed by her as part of the International Building Exhibition (IBA 1987), as a contribution to the realization of emancipatory living arrangements. With her work, Myra Warhaftig contributed to the memory of Jewish architects who were persecuted, deported and murdered after 1933.”

A kitchen as a central element of Myra Warhaftig’s apartments | Photo via frauenwohnprojekte

Christine Jachmann’s focus in this project – resulting in a building of 120 units in lot 3 of Block 2 – was on designing comfortable apartments with rooms that could be used for different purposes, based on individual needs; apartments full of light, with additional household workspaces, open-air areas, and spaces for play in the courtyard. In her reflections on the project, Jachmann notes that communication is an essential factor: “I understand my work in such a way that I listen to and take up the views, demands, and provisions that have been put forward, and the implementation of these within an overall concept falls within my area of responsibility.” She sees the emancipatory living as independent living, as prejudice-free functions and uses of space, and insists on finding new ways to interpret the demands of publicly funded housing construction. The ways of living have changed, she writes, adding: “The needs of people, which are also part of the architecture, are not constant. Everything could always be very different!”

Courtyard view of Christine Jachmann’s building | Photo by Sonja Dragovic

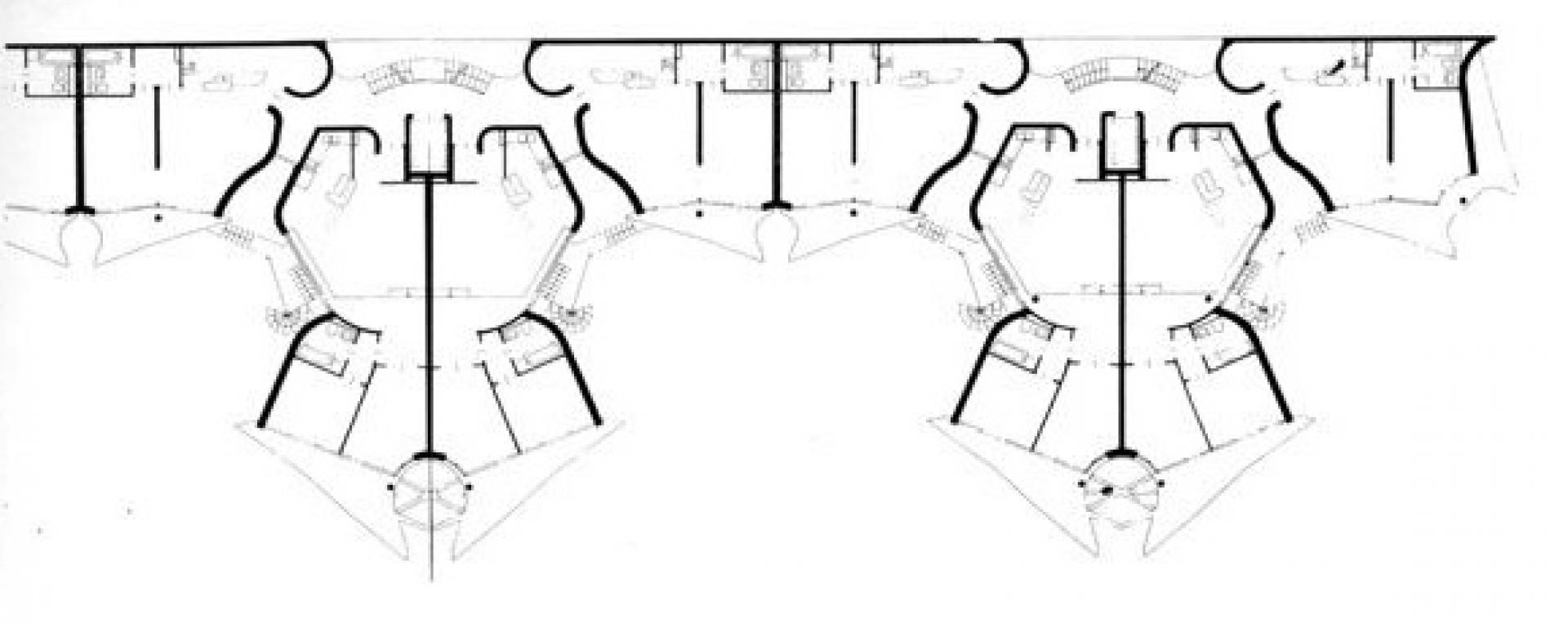

While Block 2 was planned and build from scratch as part of IBA Neubau, many other Berlin blocks – especially in Kreuzberg – were carefully reconstructed within the IBA Altbau program. One of the most famous Altbau projects, Block 70, was redeveloped by Inken Baller and Hinrich Baller, who practiced architecture together until their divorce in 1990. They designed three buildings to fill in the street façade, which had vacant voids in numbers 28, 38 and 44, and a fourth building in the courtyard. New apartments – 87 of them – were built in addition to around 200 renovated dwellings, which were done with the help of student groups, social and labor organizations and housing cooperatives. This self-help approach helped to reduce the costs of reconstruction, but also promoted direct engagement of future dwellers in the creation of their living spaces. Architects’ unorthodox approach, resulting in Block 70’s bright-colored facades and upturned balconies amongst lush greenery, made the project instantly recognizable and quite famous. As Peter Davey wrote in 1987, “the flamboyant expressionism of the Baller work made it the most popular of all IBA buildings in a poll carried out by a city newspaper.”

View of the new residential buildings in the inner Block 70 area, 1984 | Photo via Friedrichshain-Kreuzberg Museum

In an interview conducted by Dagmar Jäger in 2000 Inken Baller, an independent architect and a university professor at the time, reflected on the question of decoration for which her work and cooperation with her ex-husband became recognizable: “There is, in fact, no such thing as architecture without decoration. Even in the most reduced form, a detail or the material itself becomes decorative. Man has a desire to develop something beyond the merely unconditionally necessary, and this is the beginning of decoration.” She lists philosophers Ernst Bloch and Susanne K Langer as important influences and sees architects as socially responsible for answering the question of how we should live in the future, for striving for a concrete utopia. She subscribes to a plebeian architecture – not as populist or superficial, but multi-layered: “functional and irrational, simple and elaborate, planned and surprising, cost-efficient yet full of luxurious attributes, easy and difficult, i.e., leaving the thinking in yes/no and leading to thinking of both/and.”

Block 70: floorplan by Hinrich & Inken Baller | Illustration via Pinterest

What made the work of reconstruction within IBA Altbau framework challenging, and what also made its results impressive, was the diversity of communities cooperating to rebuild their blocks. An important contribution to this process was made by Heide Moldenhauer, a woman of many talents, who was responsible for the renovation of IBA’s Block 76/78. She studied architecture in Stuttgart and sociology in Berlin and worked for five years in DeGeWo housing in Wedding before she quit, disappointed by the violent approach in dominant practices of urban renewal. She accepted an invitation to work for IBA, though, as the Altbau renovation approach revolved around cooperation with residents. Since she was a member of a communist organization and had worked on the pro-abortion bill, an anonymous letter was sent to IBA demanding her dismissal – but Hämmer, the director of IBA Altbau, and Werner Orlowsky, the mayor of Kreuzberg, stood by her side. This and other stories about Moldenhauer’s life and work are told in Esra Ackan’s book Open Architecture: Migration, Citizenship and the Urban Renewal of Berlin-Kreuzberg by IBA 1984/87 (2018).

Block 78: Heide Moldenhauer was appointed as the architect responsible for the urban renewal of this area. | Photo by Gunnar Klack

On the importance and the progressiveness of Heide Moldenhauer work in IBA, Ackan writes:

“The participatory architecture, self-help projects, photographs, building programs, public art installations, exhibitions and events that Moldenhauer designed, produced and organized during this process not only stand as unique examples of feminist practice, but also avoid the common forms of imperial feminism and ethnographic authority during the period. After working on the general planning, she became responsible for Blocks 76 and 78, in the Kottbusser Tor area, between Oranien-, Waldemar-, Naunyn-, and Adalbertstrasse and the Oranienplatz. She took about 3,500 diapositives on the streets, in the Hof-spaces and apartments, and during the tenant meetings and the renovation process, amassing a collection which now stands is nothing less than a sophisticated city archive of the period. (…) The first empty unit renovated under her responsibility in block 76 served as a model apartment, used to gain the public’s trust. Block 76 was also the exemplary project introduced in IBA’s most visible Idee Prozeß Ergebnis exhibition catalog, where its 424 out of 551 occupied units accommodating collectively 1165 residents out of which 770 were noncitizens and 456 where children illustrated the housing problem in numbers, while Moldenhauer’s photographs provided the same evidence in images.”

Moldenhauer worked to ensure that the renewal project in Kreuzberg was opened to the ideas and needs of women and noncitizens – that their traditions can become part of the process, integrated in the way that serves them best. She encouraged and oversaw the creation of spaces for women and acted as a mediator between the noncitizen communities and social services. She also took great care of common spaces and encouraged designs that supported the ways in which residents were already using their hallways, gardens, and rooftops.

German-Turkish artist Hanefi Yeter designed murals with scenes from everyday life on the facade of one of the blocks Heide Moldenhauer was responsible for during the urban renewal. | Photo by Esra Ackan

Heide Moldenhauer, the dancer | Photo via flairberlin

Later in her life, Heide Moldenhauer became a dancer – and not just any dancer, but a driving force in the Berlin improvisation scene. According to Ackan, she had her first dance performance on her 60th birthday. In 2010, Tanz Fabrik in Berlin announced one of her show along with this biography: “Heide Moldenhauer was born shortly before the Second World War, learned various subjects until she discovered dance and performance and in 1999 performed her first full-length solo. She mainly shows solos, highly structured or completely improvised, and she sometimes teaches – so far in the cities of Berlin, Bremen, Dresden, Hildesheim, London, Petersburg, Roccatederighi, Tuscania. What you see today has been pulled out of the hat.”

These women influenced contemporary residential development in Berlin by pushing to make the process more aspirational, more inclusive, and better adapted to various needs of the city’s rapidly changing community. Their work improved IBA’s 1984/87 program and created a lasting legacy. We can only guess the ways in which IBA’s history would be altered by a more prominent and numerous presence of women from all backgrounds and communities, at every stage of the design process.

It may be difficult to imagine how merely 40 years ago women in architecture had to struggle to get a chance to work on a project like IBA, which was designed to be inclusive and all-encompassing. But that was the case, and actually, it still is. This week we celebrate the fact that the Pritzker Prize 2020 was awarded to a team of two women – Yvonne Farrell and Shelley McNamara. There are still many glass ceilings to be broken. While we strive to do that, it is important to know and tell the stories of those who came and broke them before us, for us, so that our world gets a bit better and our work a bit easier.