Dunja Krvavac: Sarajevo Days Of Architecture

Weltraum, a radio podcast about space on the jabbering Independent Coastal Radio NOR hosted Dunja Krvavac from Days of Architecture in Sarajevo. I had this great opportunity to talk about the city, her travels and thoughts in Mostar, where we met in May.

Dunja Krvavac | Photo © Ajla Salkić

How can a young female architect work in Sarajevo?

DK: It has its ups and downs, like everywhere in the world, you have different challenges. Maybe Sarajevo is a bit more specific in terms that is a still a very traditional and patriarchal community. World of architecture here is full of men, so many men. Going through this field of old white men sometimes can be a little bit challenging. I think that we all have to do small steps, we all have to be focused on what we want to do and how we want to achieve it. Working in Sarajevo, as I said, I love being here, I was born here, I was raised here, I've been living here for thirty years and have no desire to live anywhere else. I think this is a beautiful canvas that still has to be painted with a lot of things. Me staying here is a decision I made.

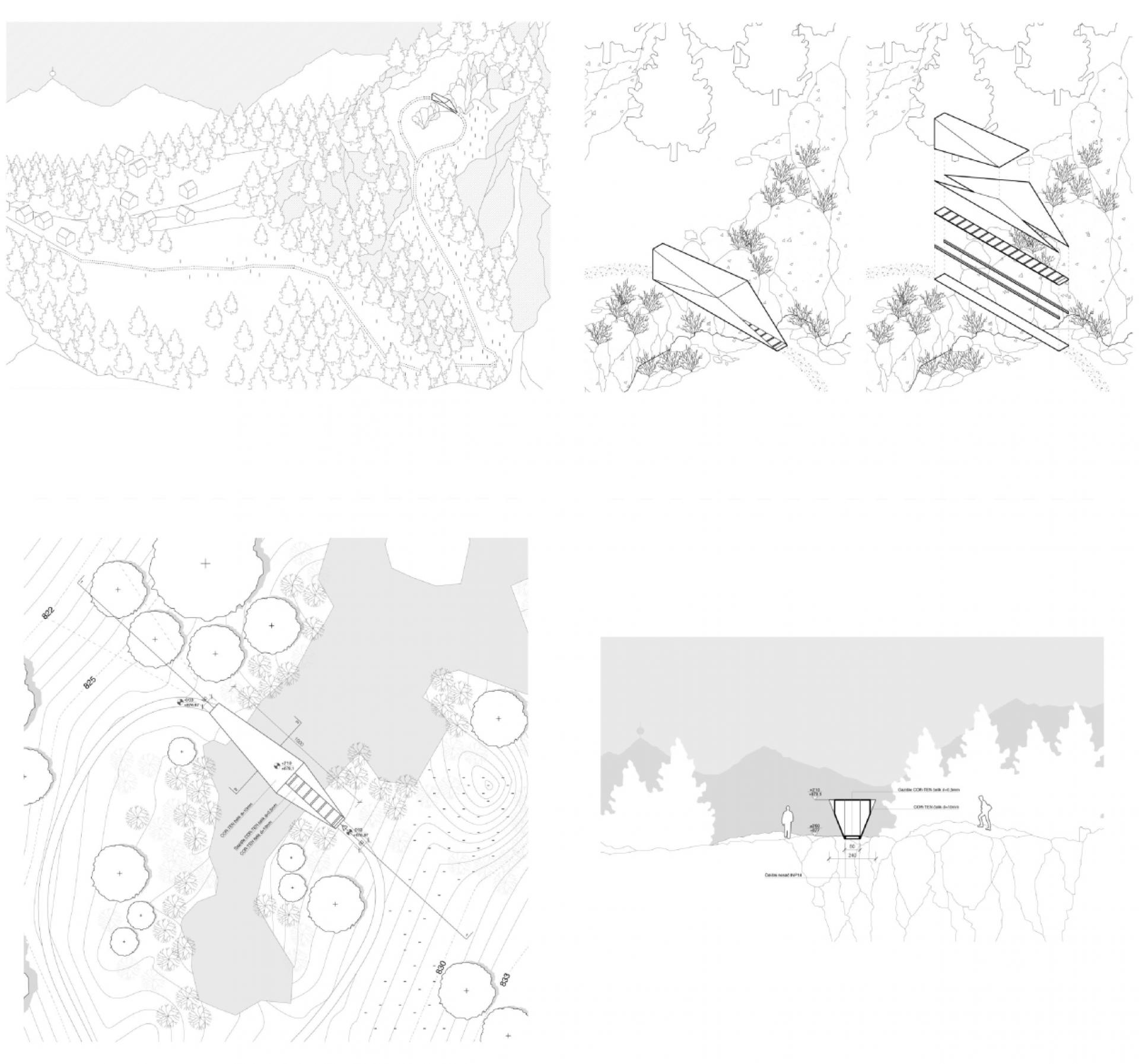

Kazani Memorial in Sarajevo (project drawings). | Photo © Dunja Krvavac

Most of the contribution that I can make into this world, I think is specifically connected to Sarajevo. Trying to be an architect here - I mean it's a cliché to say it like this that I am a girl and this is a job full of men but it happens a lot even today that you’re walking through a construction site where you have a bunch of men not taking you seriously because you are a girl. I don't want to be negative, I am very privileged as I have a wonderful job, opportunities and community of people who support me but we still have to unite in order to make this city better after all it has been through in the 1990s.

The Balkans wars from the 1990s are almost forgotten in Europe - there was a dispute in Germany that the war in Ukraine is the first war after the II WW - how did different capital intervene and defined Bosnia and Herzegovina after 1990s?

DK: In Europe people might have forgotten about the Balkan war in the 1990s but here it’s still very much present. I was born in the first year of the war, in 1992 and maybe it's a fortune that I don't remember the war. Unfortunately, due to the way that the county functions and works, we are reminded of it every day. I [as most of my generation] have this inherited trauma. This situation of us [Bosnia and Herzegovina] being in transition and the huge amount of capital flow in the late 1990s and beginning of 2000s and even now, changed the city and its architecture completely. It became a capital-focused architecture. We used to have a wonderful developing city before the war where people were eager to build the city by building schools, museum, galleries, community, culture and today everything is focused on capital and investments. There is a small amount of planning done, people just grab opportunities to earn a lot of cash when they can.

Workshop UNCONTEXT Dissecting the layers. | Photo © Sabina Hodović

Unfortunately, that's the general atmosphere now. It changed so much from socialist system transitioning to capitalism, I think we as a society still struggle to understand what is a position of an architect in this situation and context. There are a lot of people trying to be respectable towards the city and its architecture but in the end, 90% of all these efforts fail in terms that investments and politics - it's all that it matters to some people. It sounds a bit gloomy when I say all this, it sounds like there is not hope but I am an incurable optimist that things can be better. You need to make small steps and giving up is no option.

Exhibition UNCONTEXT Dissecting the layers | Photo © Sabina Hodović

Architectural Guide Sarajevo. | Photo © Timur Babić

What did the specific capital coming from Middle East to the modernist city?

DK: This influx of Middle-Eastern capital is a very difficult topic to talk about. There is a lot foreigners coming here and they want to build, invest and sometimes to even live here. That's not an issue for me if people want to invest, I don't mind that. But what I do mind is the attitude that Bosnia and Herzegovina has taken when it comes to this or any type of investors; we have this small county attitude that we just let foreign investors do whatever they want. We are so scared that everything will fall apart if we don' let them to do everything they want.

House of Memories for Memorial Center Srebrenica. | Photo © Ismet Lisica

Now we have these situations where investors are destroying most of our Olympic mountains with help of the locals. They are building huge settlements and gated neighborhoods on our mountains and the worst thing about this is that they don't really care about our traditions, customs, local experience. And we are doing nothing about it.

You are in the position of being able to travel a lot; how that influence on your work?

DK: It's a huge benefit for me that my work is connected to traveling. I discussed this with my best friend and partner in crime Irhana Šehović that we need to make our work travelabe, to meet new people in order to bring new perspectives into Sarajevo. When you are in the city for too long sometimes I have this tendency to oversee thing. You are constantly bombarded with local information that you don't filter it in a correct way. Traveling enables to connect with amazing people with new perspectives. Through LINA and other projects that we are involved in, we are making Bosnia visible again. We were visible before, we used to be an amazing county and then that horrible episode of the 1990s happened and we went some steps back. I think that everything that that we try to do here is a step forward to become better. There is no option of giving up.

What does a responsible building mean?

DK: It's a difficult question from many aspects, there is an architectural answer to that and there is a human answer to that as well. Architects are very self-centred, sometimes they [we] make buildings that are more about the architecture and the architect and less made for the community that is going to use this building.

Manifesto gallery of contemporary arts (project renderings). | Photo © Dunja Krvavac and Nikola Ostojić

I think that responsible architecture and responsible building is something where you put aside what the architecture and the architects is. That is almost not important, I always see architects as mediators. I can see space in a different way than someone else can and I can easily try to organize it. But there is an entire community that needs to use this space. It would be very narcissistic of me as an architect to say that this is an amazing building that I made and completely disregard that this building is going to be a crucial part of someone's life. If I design something it always has to be focused on the person using it. Me as an architect – I am irrelevant and not important. The only thing that is important are the people that are going to use the architecture. If you don't build for the community, if you don't interact with the community and if you don't put the community first as a part of your design process then it makes no sense.

Tell me more about the Days of Architecture and other projects that you are involved in?

DK: Days of Architecture are one of the most important projects that I am working on for almost nine years now. It's an important part of the city and regenerating the city after the war and transition.

Days of architecture 2023. | Photo © Harun Čerkez

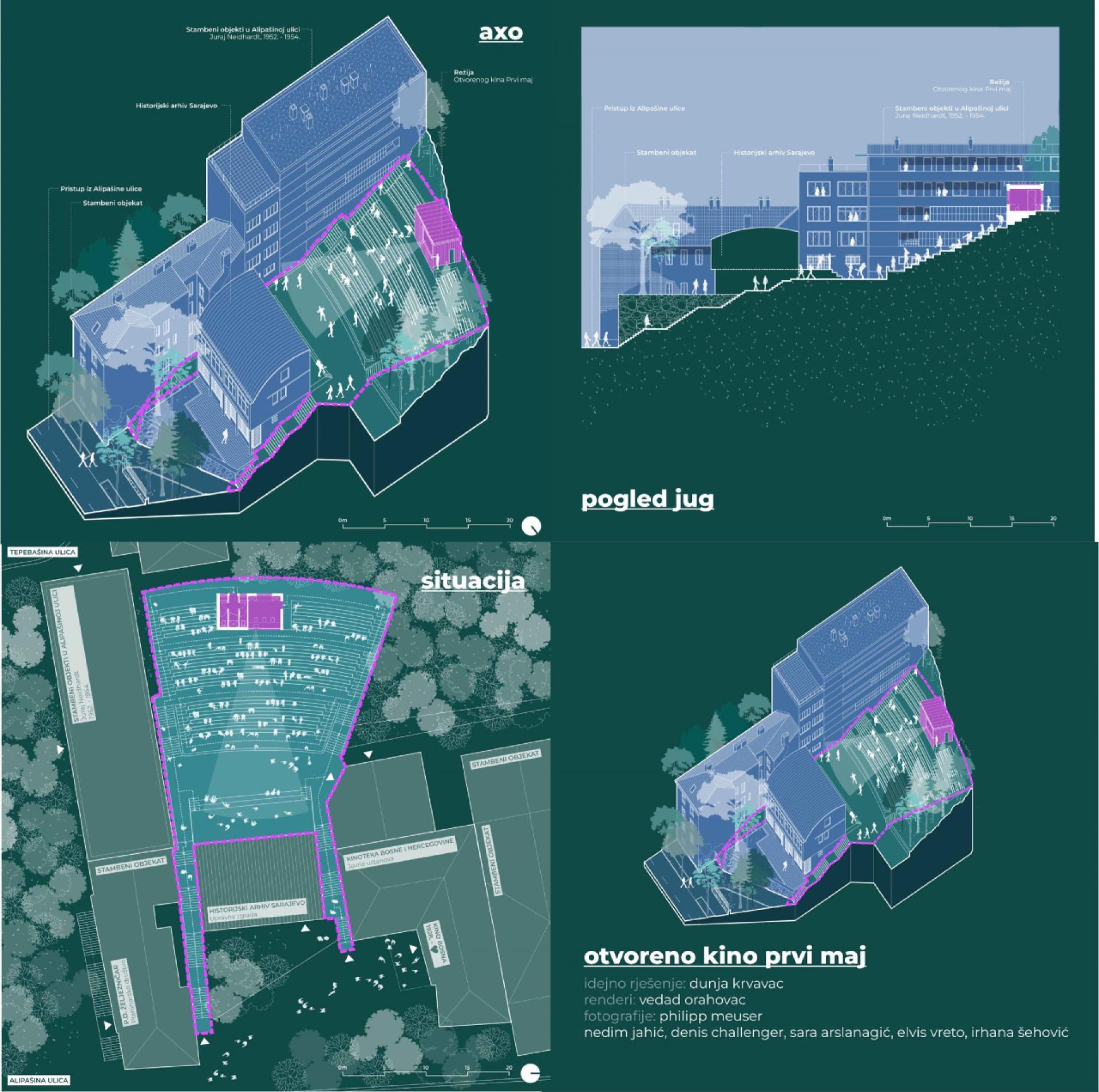

We celebrated fifteen years of Days of architecture this year. It comes down as a festival but is so much more. During the festival we gather local and international experts to discuss important topics. It a place where we can research and introduce new perspectives into our local communities as the festival is very much connected to Sarajevo. During my presentations and lectures I say “Sarajevo is our playground” to research and experiment what might Sarajevo become in the future. I am proud that we have managed to stay relevant in the city for fifteen years. We are not supported from the state so we are trying to make steps forward with the festival with the best of our capabilities. I enjoy being involved into different activist projects like the Open Air Cinema Prvi Maj in the city on which I’m working right now with an amazing interdisciplinary team.

Open Air Cinema Prvi Maj (project drawings). | Photo © Dunja Krvavac

You are good within communicating with different generations right, for example the Doršner couple which built the Olympic City of Sarajevo?

DK: It is the most precious thing in the world to bring back these people and listen to them and take in all what they have to say. I am a child of two architects and I've met a lot of architects from elderly generations at our home. People sometimes tend to put them aside and not listen to what they have to say. Especially the Doršner couple, they are like an encyclopedia of knowledge with infinity of information coming from them. Due to our [country’s] poor archiving capabilities you cannot find this knowledge in books or online. You simply have to talk to them and reach out to get all information before it’s lost.

Boštjan Bugarič, Dragica Doršner and Martin Reichert during the interview in Sarajevo. | Photo © Zoran Doršner

The Doršner couple are responsible for the fact that Sarajevo had Olympic games and that we have all this amazing architectural Olympic heritage and legacy. I met them for the first time in 2021 during production of a movie which was showcased at the Venice Architecture Biennial as part of Italian pavilion.

Dragica and Zoran Doršner in their home in Sarajevo. | Photo © Boštjan Bugarič

The three hour talk with the Doršner couple was some of the most amazing times of my life. This type to knowledge is very important for our generation to learn. Sharing information through different generations it is the most important way of keeping the knowledge alive.

What will architecture in the future look like?

DK: I ask myself this question all the time. There are so many things happening right now, from war in Ukraine to this horrible apartheid that is happening in Israel and Palestine. These situations make you wander what is the future of architecture, what is the future of the world? We have to change the way we think, we have to unlearn some things and question everything that we know. We need to be honest and very transparent. Architecture is the slowest changing profession in the world and we are still doing things very traditionally. Are we changing anything if we are working in box frames that we are working in? Having architecture for the sake of building - that's not the future. Focusing on communities, programs, systems - that we can change - is the most important thing at the moment. We seriously need to take stronger stands on many issues that are happening.

LINA Team Members. | Photo © Urban Cerjak

-

Dunja Krvavac enrolled at the Faculty of Architecture at University of Sarajevo in 2011 and finished her Bachelor’s degree in 2017, focusing on architectural design and constructive systems. In 2017, she started her Masters at the same faculty where she’s currently finishing her master thesis on urban planning and inclusive urbanism and design based on migrations. In 2018, as an Erasmus+ student, she spent one semester at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology in Trondheim, Norway, focusing her studies on urban planning and design. While studying, she’s been part of LIFT - spatial initiatives, a non-profit non-governmental organisation that aims to educate local communities on architecture, urbanism and design. She started as a volunteer in 2016 and moved on to become design team leader in 2019 and project coordinator of LIFT’s biggest project which is biennial festival Days of architecture Sarajevo and its complementary project Nights of architecture in 2020. As of soon, her interests expanded to fields of graphic and product design, resulting in awarded furniture designs, featured festival visuals and book illustrations. From 2020 she’s been actively freelancing and from 2022 she started working at a local architecture studio i.d.e.a Sarajevo. In 2021 she started working with Nikola Ostojić on various projects. She worked on Urban Lab Sarajevo, a collaborative project with UNDP BiH, Municipality Centar and Faculty of Sarajevo that focused on producing a digital platform for inclusive consultations several locations in Sarajevo. She continued exploring the topic of Sarajevo public spaces through joint Days of architecture and LINA European architecture platform project (UN)CONTEXT_Dissecting the layers: Sarajevo residency workshop.

Here You can listen to the WELTRAUM interview.