Austrian Architecture: Future Proof?

Oxford Dictionaries defines the adjective “future-proof” as follows: ADJECTIVE (Of a product or system) unlikely to become obsolete[1]

There´s a long list of architectural projects in Austria that have sustained the centuries. What we call Austria in this text has changed a lot during that period and we prefer a rather loose definition that is not confined by national borders. After all, wonderland was created in 2002 in order to transgress borders and connect young architects throughout Europe. That being said, taking into account the 20th and 21st centuries of Austrian history of architecture, one evident question comes up: which designs and ideas have turned out to be “future proof”?

Questioning common practices

In 1897, a young Austrian architect designed a temporary pavilion for a group of artists that split from the established and conservative artists´ association in order to promote their own idea of art. The city council of Vienna was then shocked by the progressive design and quickly transferred the building site from the representative “Ringstraße” to a swampy area on the outskirts of the city, where nobody would even notice it.

The project we´re talking about is, of course, Vienna’s Secession by Josef Maria Olbrich, nowadays an Austrian landmark, situated in the heart of the capital.

The Secession building (1897) in Vienna was designed by Joseph Maria Olbrich and was constructed as an architectural manifesto for the Vienna Secession. | via Secession

So, is that what “future proof” is all about? Daring a new approach, breaking with common practices in order to devote yourself to something you believe in? Looking back at these “rebels” from a hundred years ago, they´re – as most of the former avant-garde that “survived” - pretty much the classics and holy cows of Austrian tourism today. Monuments, important steps within the evolution of architectural styles.

Otto Wagner – Josef Maria Olbrich – Josef Hoffmann – Adolf Loos. Whilst the artists of the Viennese “Jugendstil” intended the “Gesamtkunstwerk”, a total work of art from building to accessories, Loos also examined how “form” is being shaped and “transformed” throughout the course of time - without the artistic mastermind behind it all. A design “by the other 90%”. [2]

Taking a look at the social dimension

Loos´s look at “design without designers” did not stop at the small scale of a chair, but also turned to “architecture without architects”. In fact, he tried to develop a concept and “Bauschule” for the “Siedlerbewegung” [3] of post WWI Vienna. These “informal settlements”, as today´s discourse would call them, were erected by homeless people in times of depression and deprivation at “Lainzer Tiergarten” and other areas surrounding the capital. Loos wanted “great architects for small houses”, but many of his ideas did not succeed due to opposition within the bureaucratic city council and even from the settlers side, who did not always understand the intention behind the designs. Still, taking a look at it from our current perspective, the whole movement, as well as the architect´s involvement in it, does show parallels to what we consider to be “future proof” nowadays, if, for example, we take a look at participatory planning and building processes in social projects (gaupenraub+/-) or “Baugruppen”, community oriented housing projects (einszueins, Robert Temel).

Beyond the problems Loos was facing back then, another reason for the diminishing presence of the settlers´ movement was the fact that in 1923 the social housing program of Red Vienna started out with monumental projects.

It´s flagship building, the Karl Marx Hof by Karl Ehn, for instance, was erected in the years from 1926 – 1930.| © 2005 by SPÖ via Das Rote Wien

On a smaller scale, Austria´s first female architect Margarete Schütte-Lihotzky joined Loos and other international architects in designing compact row-houses as part of the “Wiener Werkbundsiedlung”.[4]

Margarete Schütte-Lihotzky (1897 – 2000) was the first female Austrian architect and an activist in the Nazi resistance movement. | © Wien Museum, via werkbundsiedlung-wien.at

Vienna´s social housing program still serves as a role model for projects in other countries and a show on that topic at the Austrian Cultural Forum New York in 2013 called “The Vienna Model” turned out to be one of the most successful shows of the institution based on the number of visitors it attracted.[5] A program that you might call “future proof” as such. Still, the buildings themselves have to adapt to the change of circumstances and lifestyle of its inhabitants and the society they should serve. Is it the object in itself or the idea that should withstand the course of time? The 1930s and 1940s did produce megalomaniac structures that were meant to endure and physically still do, whilst post WWII society in Austria still does have a big problem in dealing with the monstrous flak towers from that period that are now depots, museums or just empty relics and monuments of an idea we do not wish to prevail.

Other ideas and practices, on the contrary, have taken their time until they found greater resonance in our society and have turned out to be valuable ways of dealing with current issues of sustainability and durability.

Learning from a world full of architecture

Getting back to the term of “Architecture without Architects”, the man who coined that expression with his highly unlikely, but very successful and influential exhibition at New York´s MoMA, was Bernard Rudofsky[6]. Calling him an Austrian architect would not match his biography, nor his ideas, even though he was born in the Austro-Hungarian empire and studied in Vienna before leaving for Brazil and the US. His approach was then, at the height of International Style and Modernity, so different from the mainstream that his views on what he considered to be architecture had a hard time being accepted by the architectural discourse of the time.

In the past decade though, many Austrian Architecture Schools have initiated programs of social design and architecture that might be linked to Rudofsky´s way of thinking: appreciating the world of building beyond the building industry. Architects such as Martin Rauch[7] have rediscovered clay and adobe as materials we can also use in contemporary central Europe. Looking at “non pedigreed” architecture, as Rudofsky called it in his publications, one might state that even though buildings themselves may not always last, the knowledge that is being passed on is the component that is future proof.

Go out, experiment!

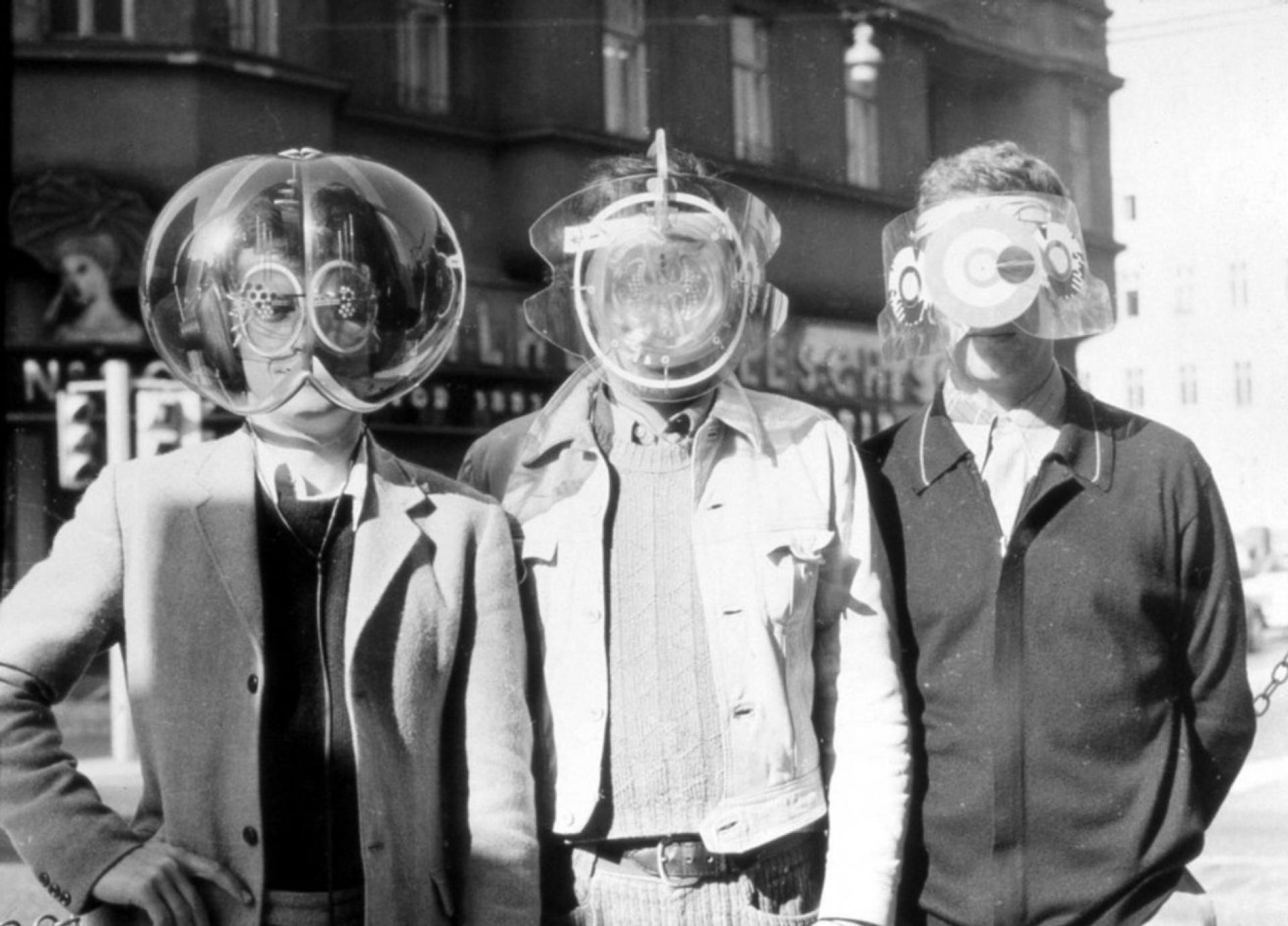

Speaking of unusual strategies, the spirit of the young rebels with a cause, we´ve mentioned in the beginning, might have lived on in the experimental architectures of the 60s and 70s by one Hans Hollein or Raimund Abraham, respectively Haus-Rucker-&Co in Upper Austria.

The work of Haus-Rucker-Co (1967) explored the performative potential of architecture through installations and happenings using pneumatic structures or prosthetic devices that altered perceptions of space.| viaSpatial Agency

What traces of “future proofness” has their movement left in our contemporary scene? Materiality? The use of pneumatic structures? Futuristic aspects that have turned into reality and are taken to another level by Austrian space architects, such as Space Craft? The freedom to switch between scales and dimensions of design? Just like Celia-Hannes or Zirup move between small scale objects, urban interventions and utopian design? Maybe it is the liberty and flexibility that young architects in Austria and beyond also show today that might serve as a guarantee for “future proofness”?

Whilst Abraham realized only few projects and spent most of his time in the field of academia, the Austrian Cultural Forum New York being one of his most well known actual buildings, Hollein became one of Austria´s most influential building architects and the only Austrian winner of the Pritzker Prize so far.

The narrow skyscraper is the venue for presentation of contemporary Austrian arts and Austrian-American collaboration in many disciplines: music, visual arts, architecture and design, digital and Web projects, literature, film and video. | via acfny

Laurids and Manfred Ortner changed their office from Haus-Rucker-Co to Ortner&Ortner in the 1980s and spent the years from 1986 on developing several large scale cultural projects, such as Vienna´s MuseumsQuartier[8], a design that was forcibly transformed numerous times by the Austrian public. In fact, it only survived due to the architects´ commitment to compromise and flexibility. Ironically, the preservation of the ensemble of Vienna´s former stables by Fischer von Erlach did not allow Ortner&Ortner to build higher that the old structure, while one of the above mentioned flak towers from WWII is visibly towering the ensemble from the side of Vienna´s 7th district.

A view of theopen space in MQ, Vienna. | © Wolfgang Simlinger, via mqw.at

So, how much adaptability and flexibility shall we provide as architects, if we want our projects to be sustainable and to sustain the often harsh winds of opposition?

Speaking of what Peter Cook called the “Austrian Phenomenon”, in his book on “Experimental Architecture”, it’s equally important to mention Günther Domenig and Coop Himmelb(l)au. Both offices were later on shaping the deconstructivist movement. Coop Himmelb(l)au also started out from a small scale, experimental and controversial point of view and moved on to be part of the starchitecture cult of the 90s and naughts. In fact, some of the architects we have chosen for the show have studied at Wolf Prix’s studio at the University of Applied Arts, Vienna.

The Steinhaus became a personal manifesto for Günther Domenig. Over the many years of its construction, it was both an outlet for his technical and formal experimentation, and a focus for his architectural aspirations. | via Wikipedia

wonderland´s focus

Given the ecological topics of climate change, shortage of resources that do and should have an impact on designers on all scales, whether it be from urban planners (Beluga und Töchter´s Urban Senses Project) to social designers, the past ten to fifteen years have shown a shift within Austrian architecture as well. For that reason, we focus on projects and teams we consider to have a sustainable approach towards architecture and society beyond common certificates and an industry that has developed around the topic. Social Design is now part of University Practice, years after Rudofsky and Papanek´s activism, now being rediscovered in Austria.[9]

Somehow, modernity´s top-down master plans have not fulfilled their promise of a stable and well organized future in prosperity and equality. The picture of the omniscient architect has, in many cases, been replaced by an eagerness from the architects´ side to learn from existing practices among “non architects”, and by the will to engage in social and ecological matters and to open the field of architecture towards discussion formats and participation even beyond office hours.

The projects we have chosen for this “Week of Austrian Architecture” deal with the idea of “future proofness” from experimental, small scale architecture and design to density (caramel) , from building refurbishment (SOLID) to the visualization of the gender gap (MissVDR), and from theory and green utopia (heri&salli) to the infinities of outer space.

We as wonderland, a platform for young european architecture based in Vienna, want to promote high quality, predominantly young teams that share with Olbrich what might be the most future proof of all – an open mind.

- by Patrick Jaritz, Bahanur Nasya, Marlene Rutzendorfer

[1] Cf. http://www.oxforddictionaries.com/definition/english/future-proof

[2] Cf. Smithsonian, Cooper Hewitt National Design Museum, http://www.designother90.org/

[3]http://www.dasrotewien.at/siedlerbewegung.html

[4] Cf. http://www.werkbundsiedlung-wien.at

[5] Cf. http://www.acfny.org/event/the-vienna-model/

[6] Cf. https://www.moma.org/momaorg/shared/pdfs/docs/press_archives/3348/releases/MOMA_1964_0135_1964-12-10_87.pdf?2010.

[7]http://www.lehmtonerde.at/de/

[8]http://www.mqw.at

[9] E.g. Applied Foreign Affairs at the University of Applied Arts, http://www.dieangewandte.at/jart/prj3/angewandte/main.jart?rel=de&content-id=1349852117885&reserve-mode=active

Austria Unfinished discussion took place on Monday 7th July, 15.00 at TU Vienna with Josef Saller (1971), Alexander Hanger (1963), Matthäa Ritter (1983), Christoph Hinterreitner (1970), Theresa Krenn (1979), Patrick Jaritz (1981), Marlene Rutzendorfer (1984) and moderated by Boštjan Bugarič (Architectuul).

Alexander Hagner (1963) founded the architecture studio gaupenraub+/- together with Ulrike Schartner in 1999. Both Ulrike and Alexander had studied at the University of Applied Arts for 3 years with Johannes Spalt before continuing for 5 years with Wolf D. Prix. Since then, they’ve worked as external lecturers for various Universities and Institutes, such as the Vienna University of Technology, holding workshops at Vienna’s BOKU, NDU St. Pölten, TU-Graz and KTH-Stockholm. Some of their most renowned works include the “Eiermuseum” they’ve designed for sculptor Wander Bertoni in Winden am See, which has won the “Burgenland Prize for Architecture"and was nominated for the Mies van der Rohe Award, as well as the refurbishment and extension of MCM Klosterfrau Melissengeist that received the ETHOUSE Award and the recent redesign of the offices of Franz Schellhorn’s Agenda Austria. Beyond that, for the past ten years gaupenraub has engaged in social projects, such as "Vinzi Rast”, but also Memobil furniture for people living with dementia or “VinziRast-mittendrin”, where students and formerly homeless people live together, which has been granted the Urban Living Award 2013.

Theresa Krenn (1979) studied architecture at Vienna University of Technology and the Academy of Fine Arts, Vienna from 1999 to 2005. Between 2005 and 2007 she worked in various architects offices (Vienna and Paris). 2007 Artists and Architects in Residence Program of the MAK Center in Los Angeles. Since 2008, founding partner at studio uek, since 2010 lecturer at Vienna University of Technology, Department of Urban Design. Since 2014 she´s a lecturer at Vienna University of Technology, Department of Building Construction and Design.

Josef Saller (1971) and Heribert Wolfmayr (1973) – heri&salli- work on spatial drafts, architectural horizons; they work with interventions, bound to surroundings and landscapes, which reach their targets in materiality in relation to the people. By opposites, put into interlinked connections, an architectural idea - as a collection of different substantial barriers and surfaces – reaches its concept and necessity in connection with material, open space and human being. Man as active being always is the reason for possibilities of architectural drafts.

Christoph Hinterreitner (1970) was born in Vienna, studied architecture at the TU Vienna, the TU Graz and the RWTH in Aachen, and history of arts at the University in Vienna. After working in architectural offices in Vienna, Cologne and Paris he founded SOLID architecture. SOLID architecture is a Vienna based practice, set up in 2000 with Christine Horner. The team provides solutions to sensitive and challenging public tasks, often in combination with the reuse and reinterpretation of existing building structures. Their work focuses on buildings for education, corporate architecture, bridges and exhibition design. SOLID architecture has among others completed projects for the Austrian state, the Austrian pavilion at EXPO 2008, the international office furniture manufacturer Bene, Austria’s leading electricity provider Verbund AG and the Austrian Lotteries. All projects origin from successful competition entries. SOLID architecture’s projects are regularly published in international journals.

Matthäa Ritter (1983), graduated in 2008 from the Academy of Fine Arts, Vienna and co-founded the studio missVDR in 2010 together with Julia Nuler and Theresa Häfele. MissVDR are looking exactly for the solution that fits the circumstances and requirements of a given place. Unused potentials are activated and independent paths are taken. They try to get to the essential of an object, without losing a holistic approach. With every project they remain open for new perspectives and alternative models. Cooperation and communication is very important for them, both with specialists and with each other. In this sense they understand the users as well as experts, not only the project partners and professionals.

wonderland

Marlene Rutzendorfer (1984) studied architecture at the Vienna University of Technology and ENSA, Paris, La Villette, as well as theatre studies at the University of Vienna. Combining these studies, she’s been assisting stage designers at Vienna’s Burgtheater and at the Salzburger Festspiele. After doing curatorial assistance for the “Vienna Model” at the Austrian Cultural Forum New York in 2011, she joined wonderland in 2012 and together with Levente Polyak initiated the “movies in wonderland” series, an internationally traveling architecture film festival that has found its base at Vienna’s MQ after a successful cooperation with Az W and frame(o)ut in the course of the wonderlab exhibition in 2013. Marlene is currently working on her PhD on Francis Kere’s architecture with a particular focus on the influence of Kere’s work on the “Opera Village”, initiated by German artist Christoph Schlingensief. In 2014 she held a creative workshop at the school of the Opera Village in Laongo and visited Gando, where she participated in a workshop with USI Mendrisio.

Patrick Jaritz (1981) graduated from Vienna University of Technology and is currently spokesman of IG Architektur (www.ig-architektur.at), a political association of architects and architecture contributors. Since his engagement as head of the students union at the architecture faculty and later as national coordinator for the European Architecture Students Assembly (www.easa.at) he got many opportunities to take part in different architecture communication projects. Since 2012 he is holding workshops on body-space relation (www.kukiwonderland.org) and takes part in the research project Berufsfeld 2.0 (www.berufsfeld.at), a detailed investigation of the professional circumstances in the field of architecture production/activism. He joined the Wonderland board in 2013. www.patrickjaritz.at