Slovakia Unfinished

The 20th century was a turbulent era which influenced not only Slovak history but also Slovak architecture. There are several periods which can be distilled which reflect both - political and architectural tendencies. Politics and architecture are often connected, especially so in Eastern Europe.

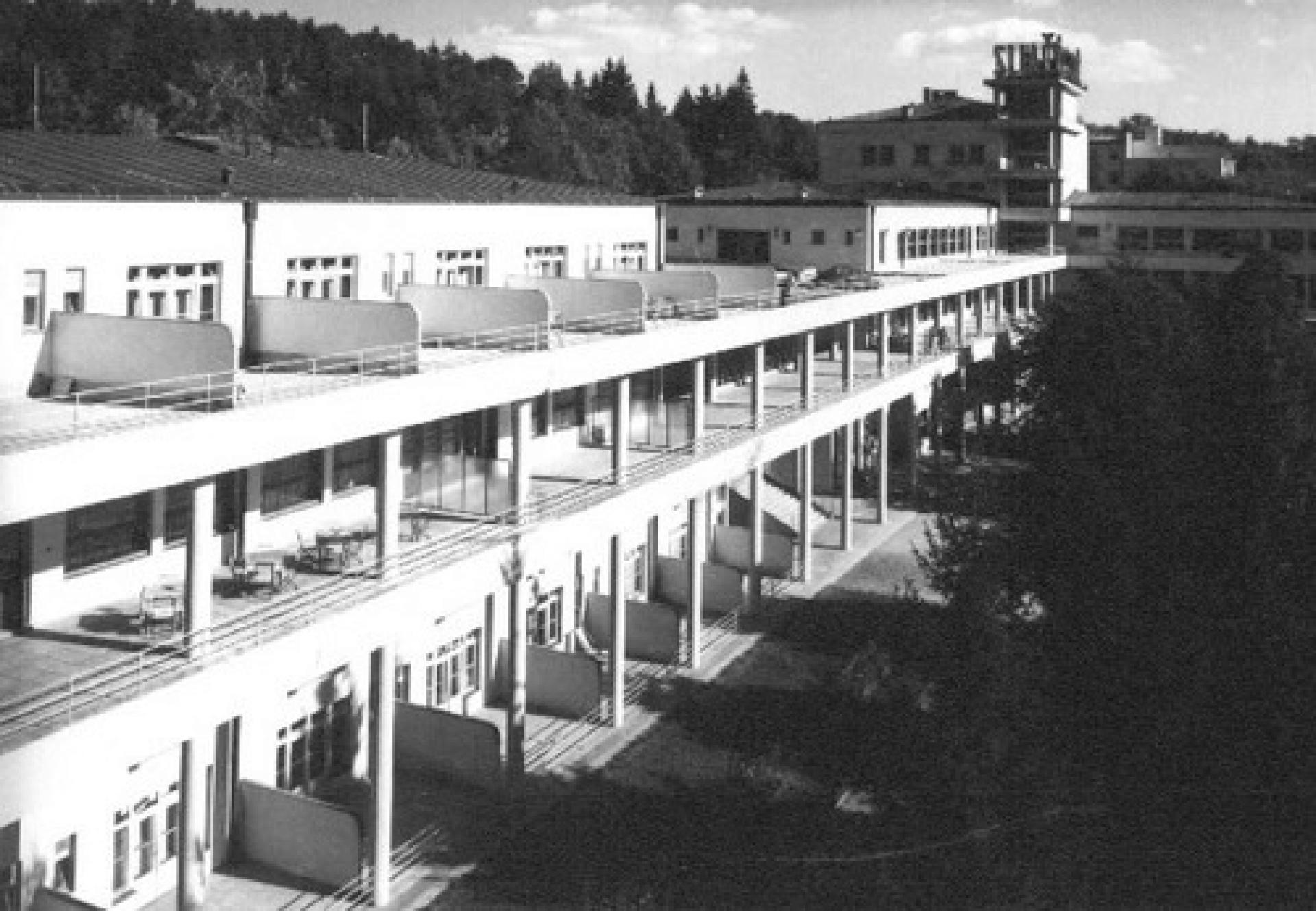

Apartment Block Avion by Josef Marek is a successful combination of a unified urban parterre with a Functionalist dispersion of masses in the upper floors. | photo by ÚSTARCH SAV

Until 1918, the region of nowadays Slovakia was part of Austro-Hungarian empire, strongly influenced by Hungarian politics and culture. Slovak culture and architecture was hidden, but existed in spite of political situation. During this period some of ethnic Slovak architects situated their life and work in Czech countries which were very familiar both in language and culture. Dušan Jurkovič based his office in Brno, Morava region, and created some of his famous works there. Some of the architects, such as Michal Harminc, or Ludwig Oelschläger, who were mostly educated in Budapest, made a career in upper Hungary before 1918. The period of Slovak architecture before 1918 is strongly influenced by Hungarian secession, historicism and eclecticism.

The Federal Parliament of Czechoslovakia by Karel Prager was after the dissolution of Czechoslovakia used by Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty until November 2008. | via Houser

In October 1918, Czechoslovak republic was established and modern Slovak history was born. This new atmosphere of democratic and modern state created conditions for social and cultural development. From the begging architecture was one of the most important part of creation of new national Czechoslovak identity. Since 1918 many Czech architects came to Slovak part of the republic to develop state infrastructure. During 1920´s, Czech architectural cubism from Prague found many possibilities for realization in Slovakia. But soon, modern movement from France and Germany entered into Czechoslovak architectural scene and quickly naturalized. In 1930´s, Czech architects like Jíři Grossman and Alojz Balán, both based in Bratislava from the begging of common state, created pure modern architecture which is today iconic part of Bratislava city scape. Others, like Jaromír Krejcar, Bohuslav Fuchs and Rudolf Strockar found place for actualization of their progressive architectural thinking in Slovak rural countryside, in spa towns like Trenčianske Teplice, Sliač and High Tatars. These places became an experimental ground for avant-garde modernist architecture. Slovak architects of this era ‒ Friedrich Weinwurm, Ignác Vécsei, Juraj Tvarožek, Vladimír Karfík ‒ built architecture for new upraised middle class and strong private investors. Villas, apartment houses, banks and department stores are memorable ikons of this period of time until today.

The Slovak countryside adopted the avant-garde modernistic architecture in SPA resort Sliač by Rudolf Stockar. | via ÚSTARCH SAV

After World War II, in 1948, communist regime took power in Czechoslovakia. The continuity of modernism was forcibly aborted by implementation of socialist realism. This new style was in Slovak part of Czechoslovakia official only until 1953. Shortly afterwards modernist tradition of Czechoslovak architecture was slowly resurrected. The year 1963 was a breaking point in Slovak culture and architecture. Social and cultural potential and optimism accompanied by political remission created a melting pot which erupted in 1968 in Prague Spring. Unfortunately all this social movement was suppressed by Warsaw´s pact intervention. Great architects like Ivan Matušík, Vladimír Dedeček, Štefan Svetko and Ferdinand Milučký created their greatest architectural works during this short period of time. During the next decade, some of the revolutionary architectural concepts were slowly realized, but political depression after the invasion did not allow for such a creative atmosphere and optimistic will as there was in late 1960´s.

One of the important architectures from sixties represent the Slovak University of Agriculture in Nitra by Vladimír Dedeček. | by ÚSTARCH SAV

Last decades of socialism relied on planned economy and directive urban planning. In Slovakia, mass housing development continued despite of critique. Economical and social gap between western countries and eastern socialist block in this decade spread rapidly, in Czechoslovakia hand-in-hand with proceeding normalization which dictated political as well as cultural norms after 1968 soviet intervention. This atmosphere suppressed all spheres of society as well as architectural thinking, which was no longer as progressive as it was in late 1960´s. In early 1980´s, postmodern movement entered Slovak architectural scene and found several realizations in Slovakia before the end of communist regime in 1989. Ján Bahna was one of the pioneers of this movement, his interior interventions in department store in Ružinov became iconic postmodern quotation. Other architects, like Pavol Paňák and Martin Kusý, co - authors of New Building of Slovak National Theater and headquarters of Slovak National Bank brought architectural discourse of critical regionalism, which in their case was inspired in both local tradition and language of functionalism.

Year 1989 is another key moment in Slovak modern history, which influenced continuity of architectural thinking. The state, as a hegemonic initiator and investor, was replaced by private sector. In 1990´s, the scale and amount of investments shrink rapidly. Slovak architecture, under the influence of postmodern thinking, found inspiration and roots in tradition of modern movement of 1930´s. Private sector reported scale and needs comparable with the era of first republic of Czechoslovakia. The beginning of 21st century brought new goals of private sector. Private investment in large apartment development as well as popular shopping estates brought a need of new architecture which was supposed to be cheap and quick. This era is typical for its sometimes lawless and unrespectful interventions to the architectural heritage, without creating a new quality. Progressive architecture can be found in small scale of individual housing project and in low cost cultural projects (in many cases created and funded as DIY).

Today’s small scale design like Matuškovo Gas Station follows the period of sixties. | by Atelier SAD

In the last few years, a visible tendency, has appeared in in Slovak architectural scene, to follow the story of the great era of 1960´s, when the courage of individual architect had lead into progressive design and iconic realizations. Gesture and monumentality is again the modern dictionary of Slovak architecture, but it is pragmatically mixed with small scale design and fine craft. Lack of state operated investments into social infrastructure in the last 20 years created huge potential for the future. Hopefully, Slovak architects will cope with this public need and create design for 21st century, which would represent actual era at least as clear as did the architecture of the past 100 years.

- Martin Zaiček