In Memoriam: On Metaphors Of Spasoje Krunić

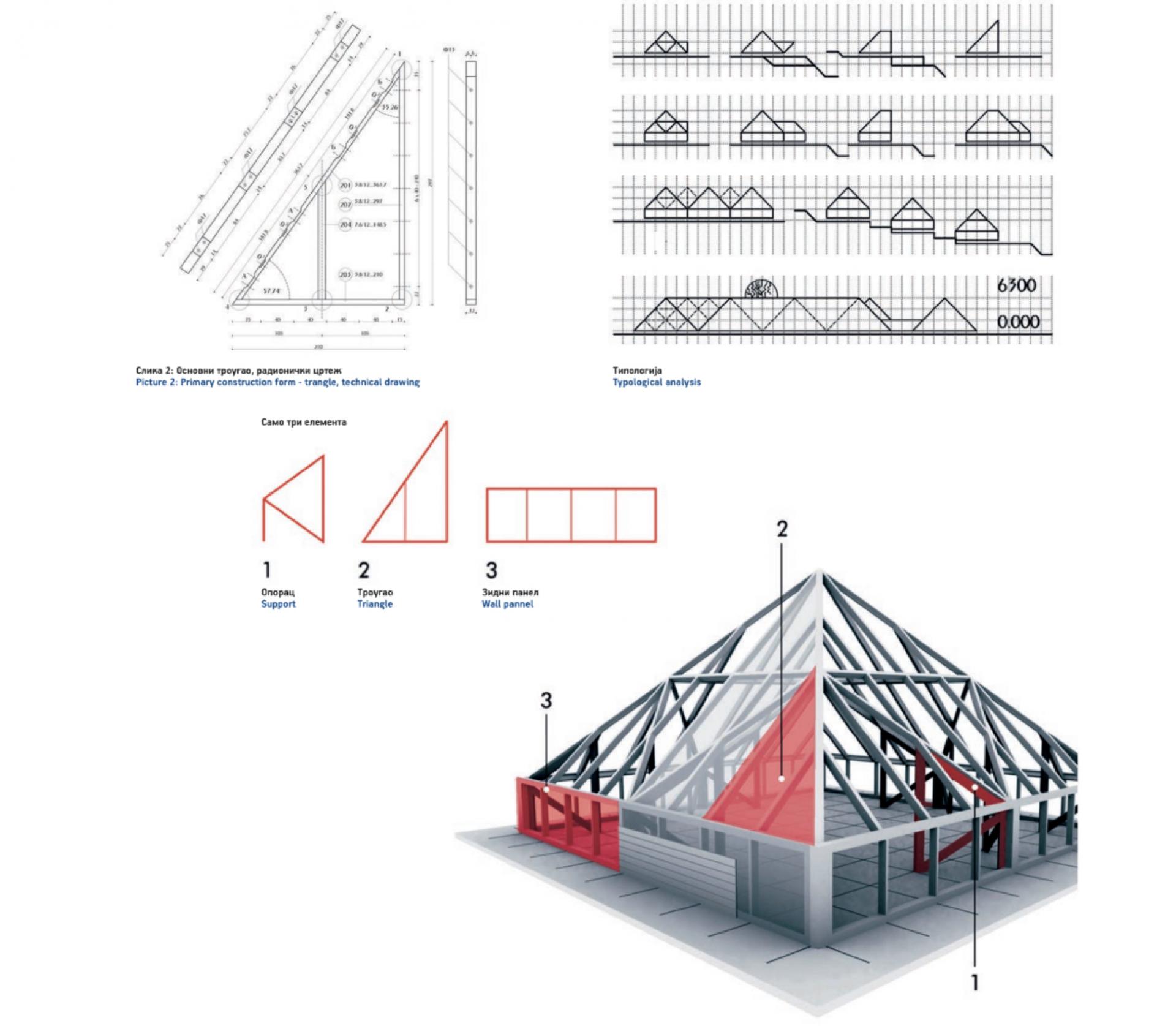

Exactly six years ago the Unfinished Serbia tour took place in Belgrade, where we have met prof. Spasoje Krunić, an architect, educator and fighter. He strongly believed that Architectuul has an important influence on the dissemination of architectural knowledge, therefore he was devoted to our stories, which he could follow regularly online. In his last post to Architectuul he shared his model of primary construction form for the village for refugees.

His lifetime determined a change of three different countries, born in the Kingdom of Yugoslavia, lived and worked in socialist Yugoslavia, and died in today’s Serbia. His work was influenced by the architecture of Louis Kahn, Frank Lloyd Wright, Le Corbusier and Jože Plečnik.

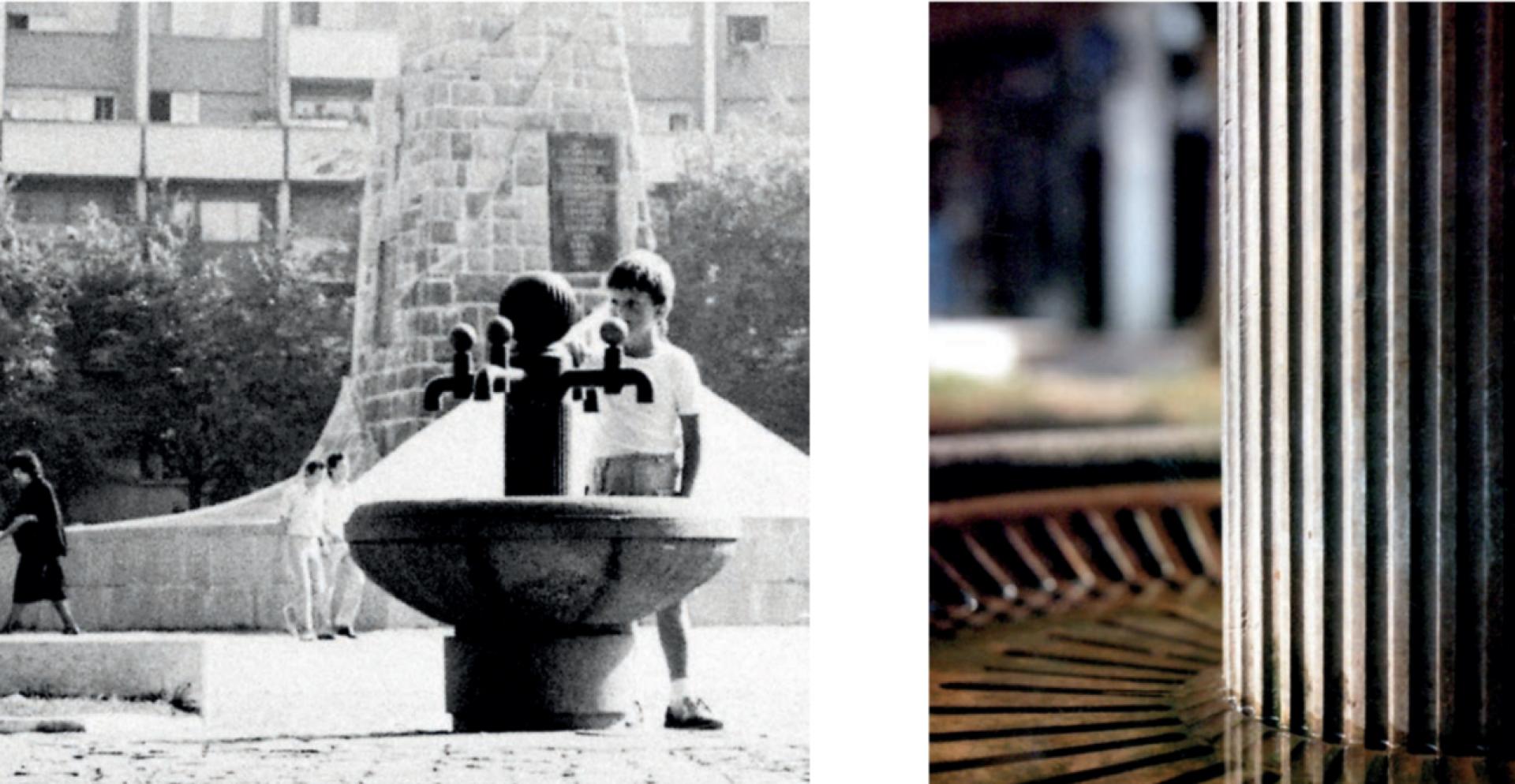

The play of the light and shadows in the Memorial Ravna Gora (1998).

***

Here I will not talk only about the creative work of the architect Spasoje Krunić. I am more inclined to talk about his courage and determination to persevere faced with pressures of the world we live in. His metaphors, both in architecture and in public life, increasingly assure me of this.

I do not intend to interpret his work and even less so his life, nor is my aim to address representation, which really says nothing about represented. My intention is to look at things and relationship between things in his life and work from the standpoint of objective phenomenology.

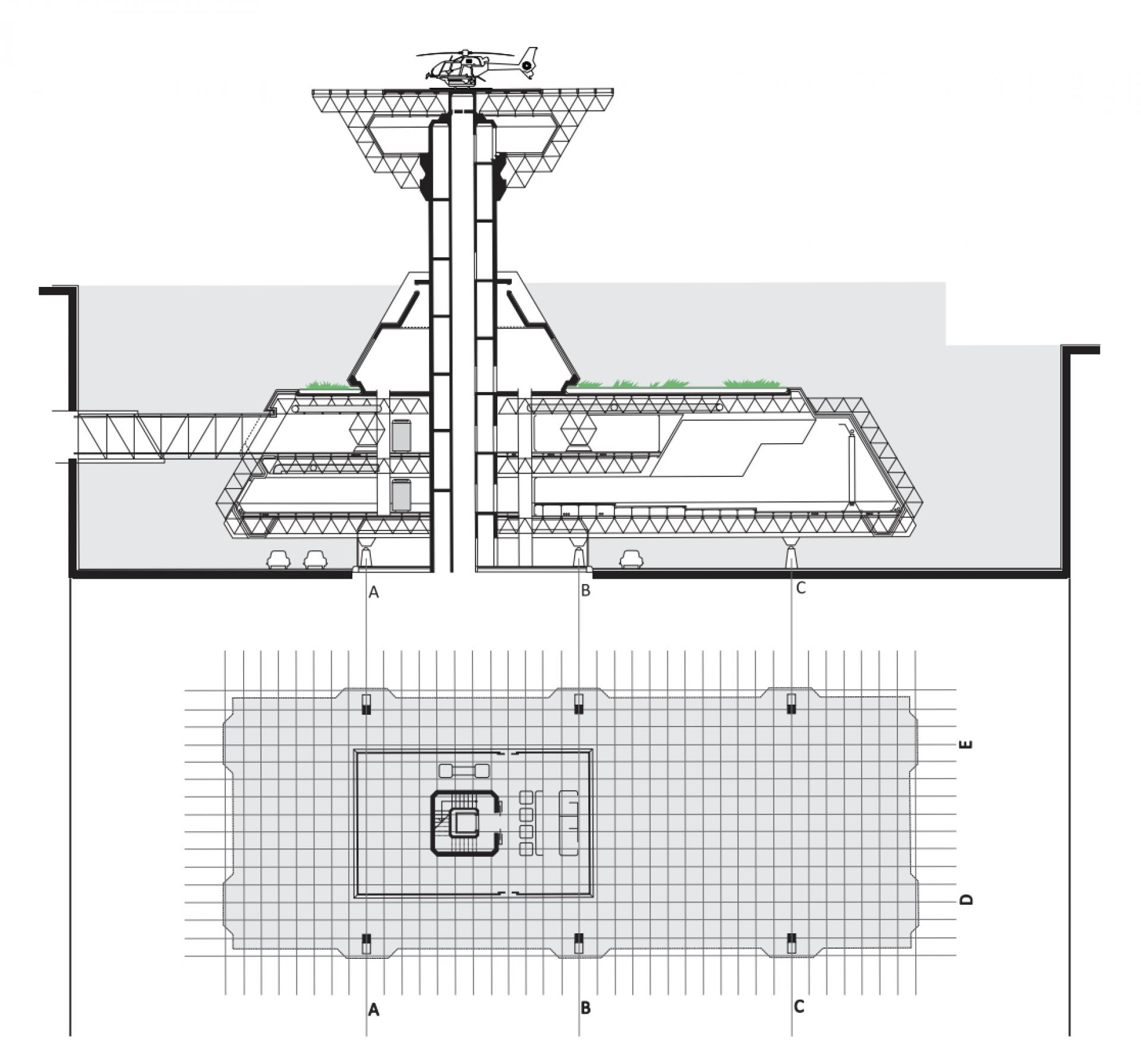

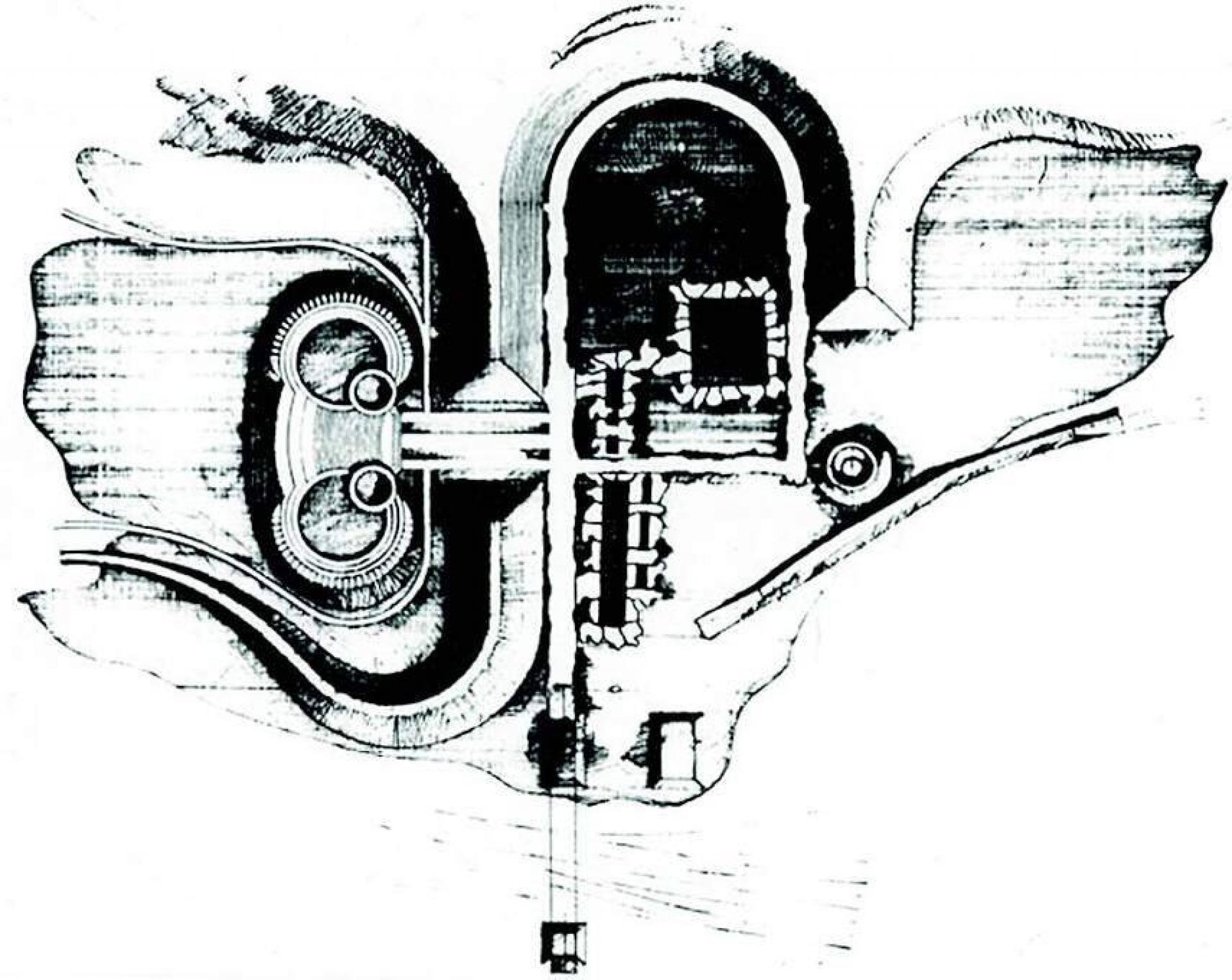

Police Command and Operation Centre in Belgrade (1979).

Of course, it is quite possible and I am certain that I know little about the personal history of Spasoje Krunić. But little that I know I learned from his metaphors – or rather creative allegories inspired and instigated by his strict adherence to the principles of modern architecture and the modernist movement, to the extent it was possible, given the reactionary and revisionist period in which he has been creating.

I will not talk about the childhood of Spasoje Krunić, not because I know practically nothing about it, but mostly because childhood is a hazy period that our minds know nothing about. For this reason, I will talk about his youth and adulthood. In fact, I intend to present and prove the hypothesis that Spasoje Krunić, in his life as well as his creation, he was in some kind of situation of his own, that he has been is true to the ideas of universality and singularity – he would call it communality. During his studies of architecture, he already manifested virtues to a high degree, which he lived by all his life. In this period, he advocated energetically that the academic community should gather and unite around progressive ideas that would lead up to the changes, which brought him into the very centre of social events at the university. Back then, he had an outstanding level of militant spirit thanks to which he tackled problems directly. His vigilance and attention paid to the milieu he lives and works in and to architecture above all, have stayed with him to the end of life.

I do not want to omit here, but on the contrary, I intend to point out in particular the relationship of Spasoje Krunić to his professors and seniors. Such an attitude indicates his spiritual health, which will follow him for the rest of his life despite the difficult times we live in. What he set up back then, and the way he did it, has been developing to the end of life.

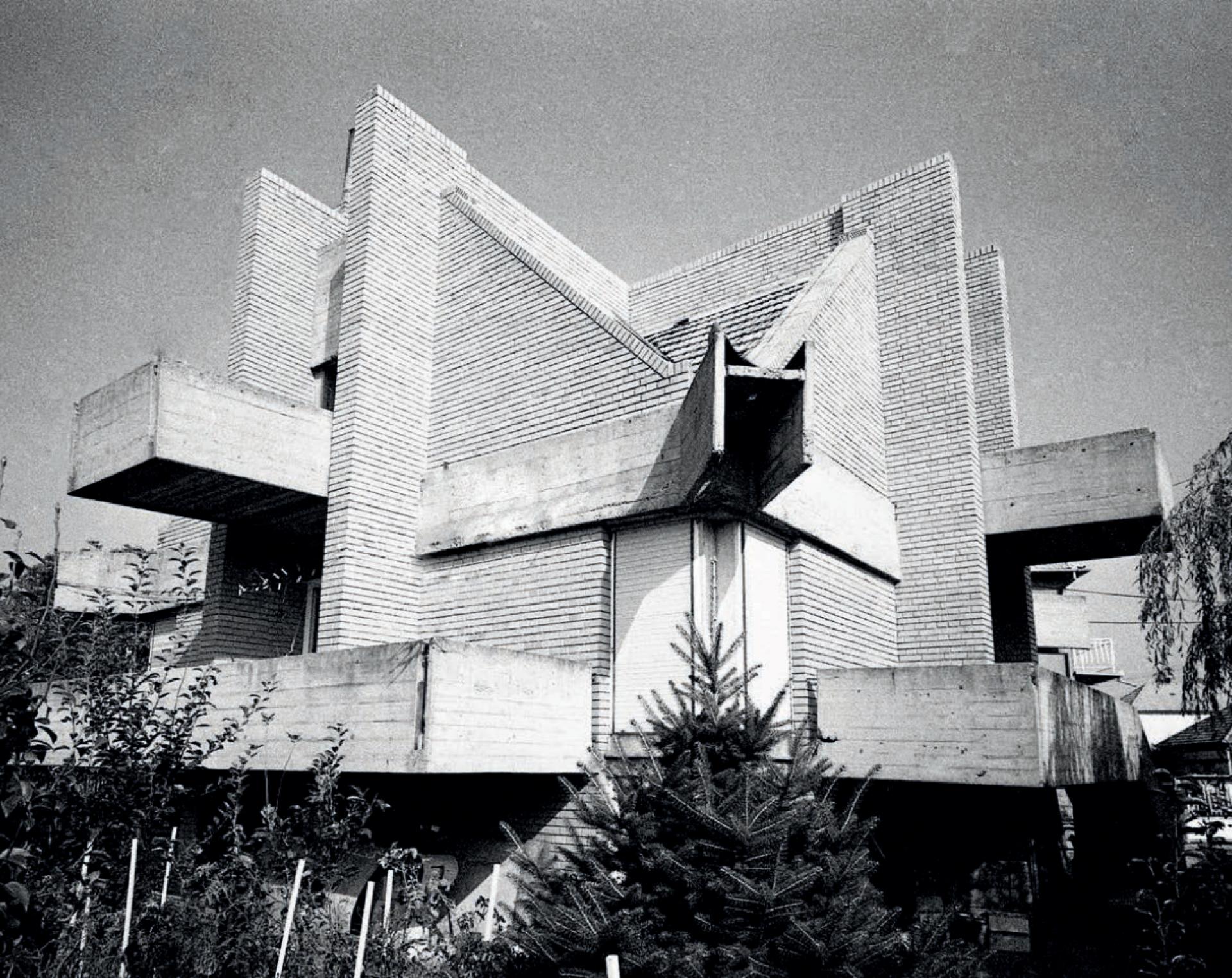

Tašin-Bugarin House in Zrenjanin (1980).

Following his graduation, young Spasoje Krunić faced his first significant and major professional and creative challenges. On the one hand, he acquired extremely important experience, creating in situ in small communities in Serbia, strengthening his character and preparing himself for major masterly projects. In this period, he created beautiful metaphors, in my opinion, for the relationship towards climate and place, materials, structure and proportion, in works that are here to stay, such as: Gallery Jovan Popović in Opovo (1969-1970), The Cemetery of 6 000 people executed in 1941 in Kraljevo (1970-71), semi-detached house Tašin-Bugarin in Zrenjanin (1975-1980), which represents, in my opinion, the final phase of his youth. It is easy to notice that, at the very outset of his creative period, these metaphors were a homage of a good student to his teachers or, as he likes to call some of them, to the apostles of Serbian architecture – Bogdan Bogdanović (relationship to place and landscape), Nikola Dobrović (relationship to structure), Stanko Mandić (relationship to material) and Milan Zloković (relationship to proportion).

His dedication and commitment, and above all an extraordinary discipline in creation through all phases of appearance of the Being-here-in-the-World, as well as his exceptional perseverance in being present on the spot, it is all visible even today in the durability of the very logic of his work – from masterly and perfectly elaborated and implemented details to brilliant articulation of architectural shape, form and space. Thus, in the period of his youth, he created first things in art (experimenting with structure, proportion, form and place), in politics (experimenting with social engagement) and science (experimenting with construction, materials and urban planning). It was a remarkable and important preparation for a phase that I will refer to as his adulthood.

The Cemetery of 6 000 people executed in 1941 in Kraljevo (1971).

I will refer to the third phase in Spasoje Krunić’s life as adulthood rather than his maturity because he has shown and proven his maturity early on, during his studies of architecture, as well as later on, over and over again. In his adulthood, he has slowly but surely caught up with his teachers, becoming a teacher himself and a man of influence and respect. He has been and still is in his own creative path - in a situation of his own. The first signs and confirmation of Spasoje Krunić’s maturity included the following works: Prison for Foreigners in Belgrade (1979-1983) and the Police Command and Operation Centre (KOC) in Belgrade (1979-1983), which received significant awards and public recognition. Although the design of KOC has shown that Spasoje Krunić is a constructivist architect, with his patents of structural systems for building single-storey and multi-storey buildings he has shown and proven himself to be an innovation architect.

Mijatov House in Zrenjanin (1972).

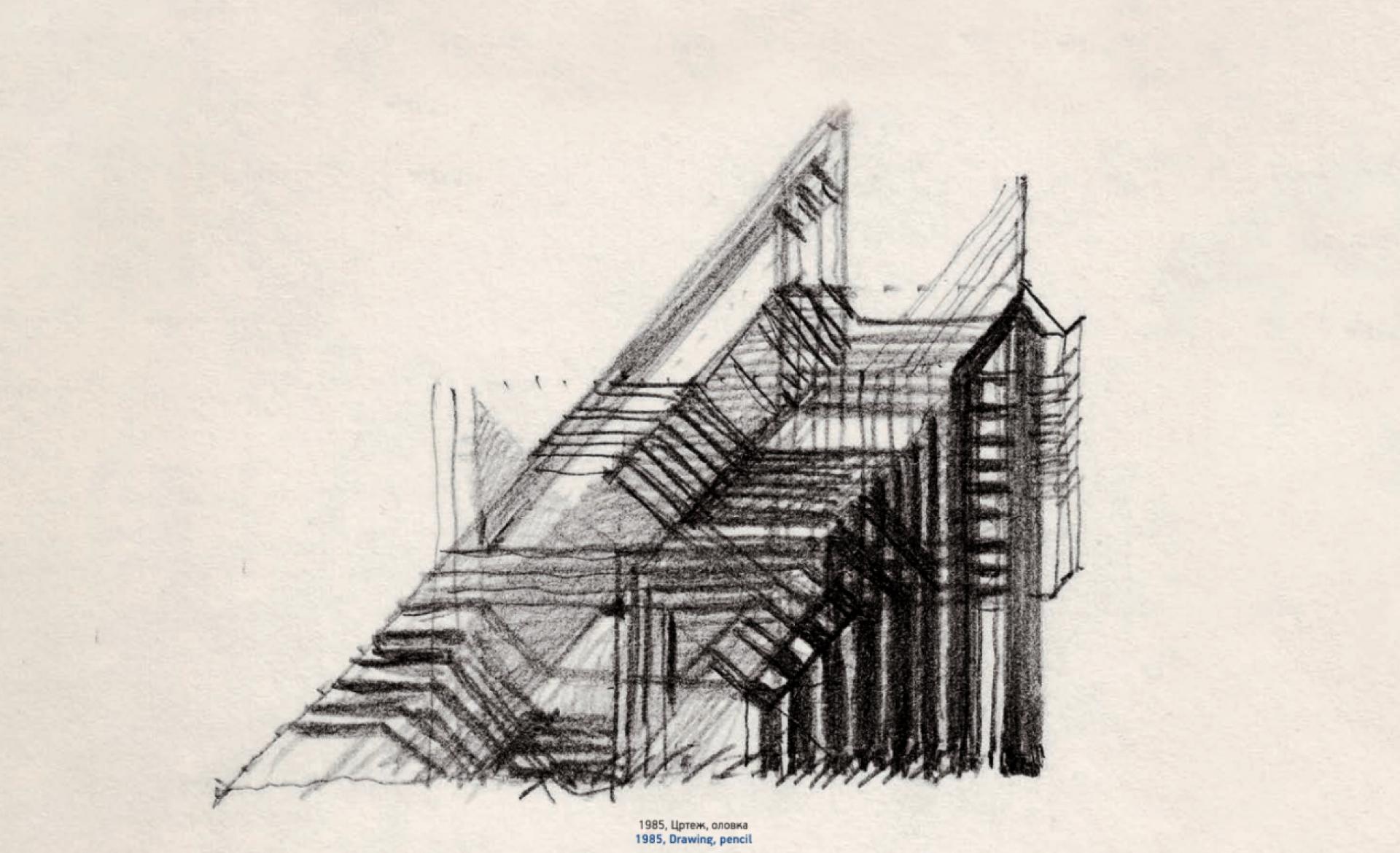

He received awards for his metaphors on the international scene at international competitions: Warsaw confrontations in Warsaw, Poland (1986) - Minister of Culture Award, and the Presidential Palace in Baghdad, Iraq (1988) - First Prize. In parallel with these significant achievements, he got involved again in sacred architecture, which has remained since 1963 a special and unavoidable part of his creative work and personal preoccupation to the end of life. In particular, I would like to single out the monument Tomb of war orphans in Konarevo near Kraljevo (1985) and the Monument Suzić in Sombor (1985) as outstanding abstract cubism metaphors for memory.

Juvela Office Building in Belgrade (1972).

Tomb of war orphans in Konarevo near Kraljevo (1985).

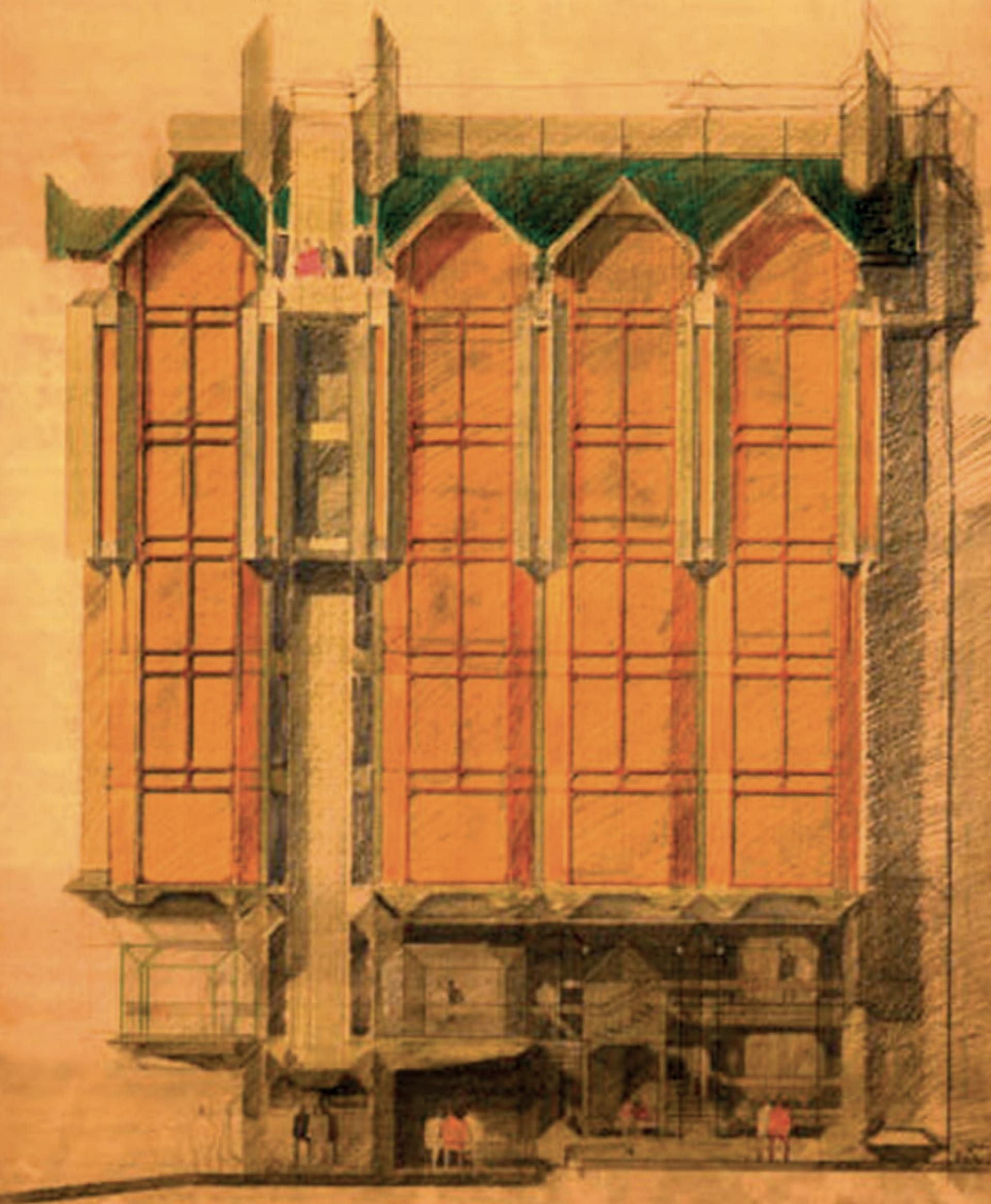

The final phase of Spasoje Krunić’s adulthood begins in 1995 when he carried out his design of the Office Building in Knez Mihailova Street in Belgrade (1990-1995) and Zora Palace in Belgrade (1994-2005) when he formally began his successful academic career. In the same period, he bravely decided to become actively involved in the political life of Serbia in order to help the country get back on the right track it had diverted from in the 1990s.

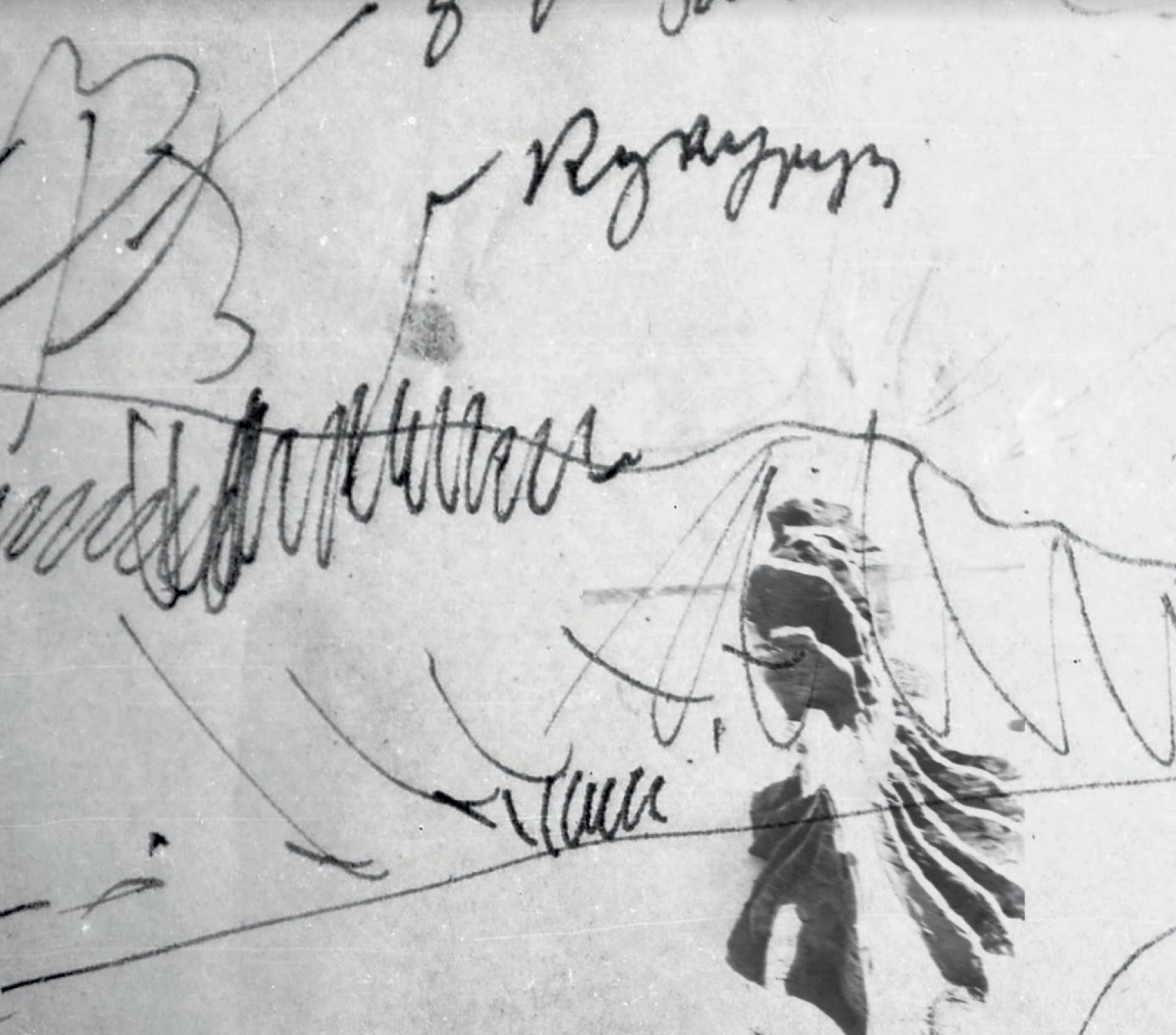

The model of primary construction form for the village for refugees shared for the time of crisis in 2015.

Even though his formal academic career has begun relatively late, there are few who could pride themselves on academic successes which he achieved. Spasoje Krunić, like hardly anyone else, has manifested exceptional dedication and loyalty to the Faculty of Architecture in Belgrade ever since he was a student, thus leaving his undoubtedly positive mark on the University of Belgrade as a legacy for generations to come.

As the president of the Belgrade City Government, he attempted to organize and restore Belgrade after years of neglect to the extent this was possible at the time. At that point, an ominous fate befell him when NATO forces bombed Belgrade in 1999, so he had to manage organization of the city under war conditions. There is no worse thing that can happen to an architect/creator, I argue here, than destruction of a city and life!

Drinking Fountain in Kraljevo (water is life!) (1982).

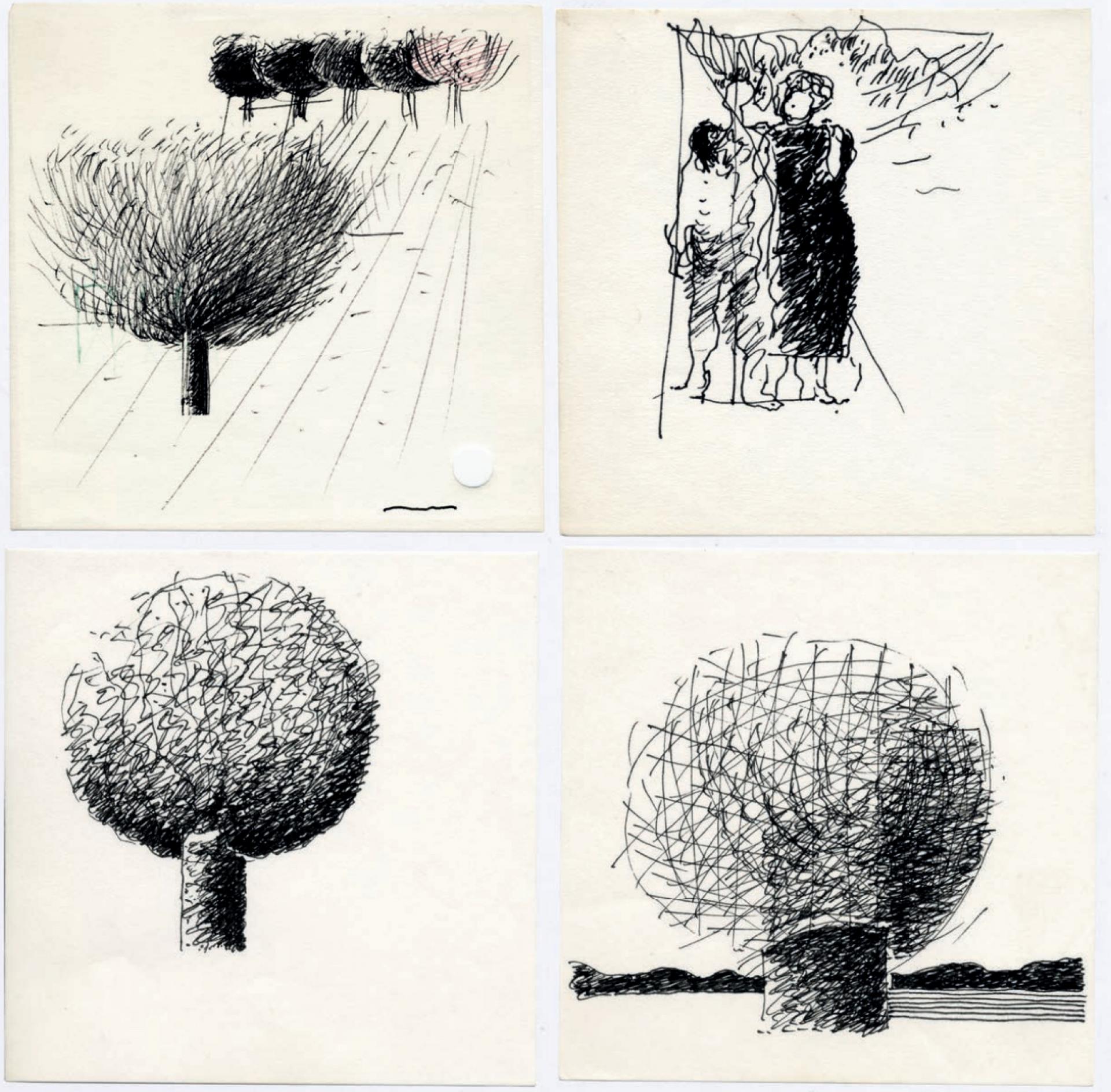

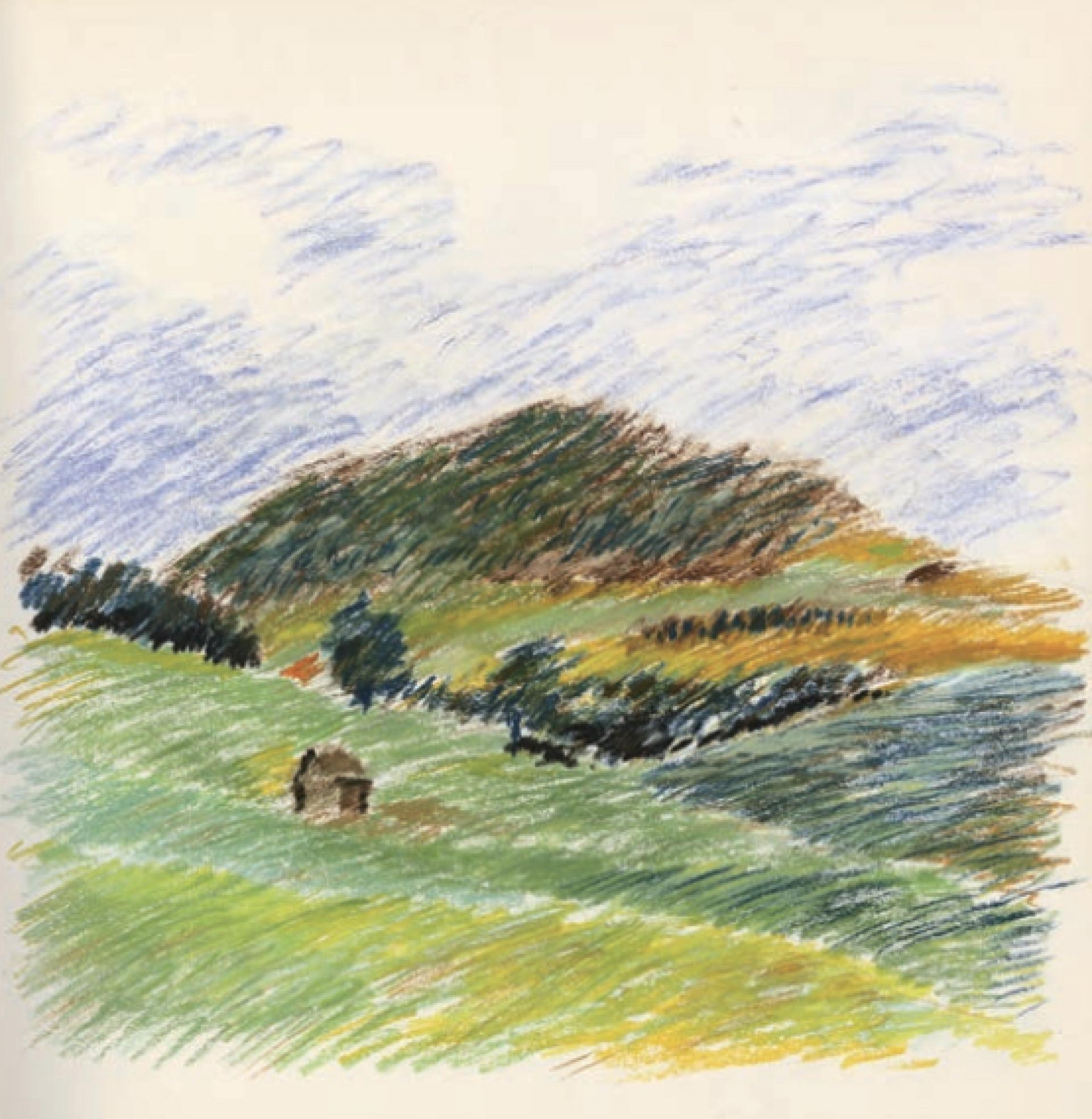

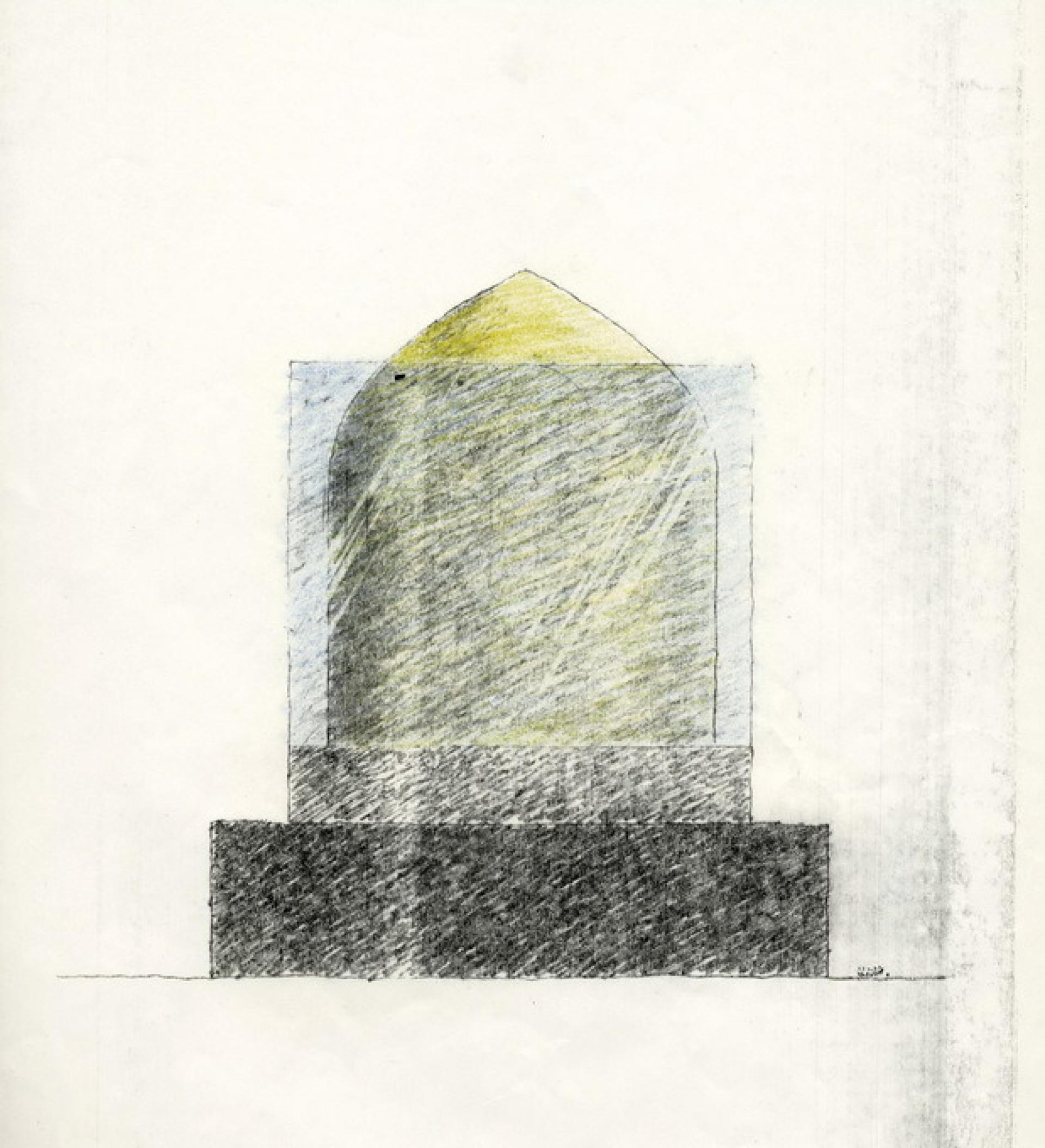

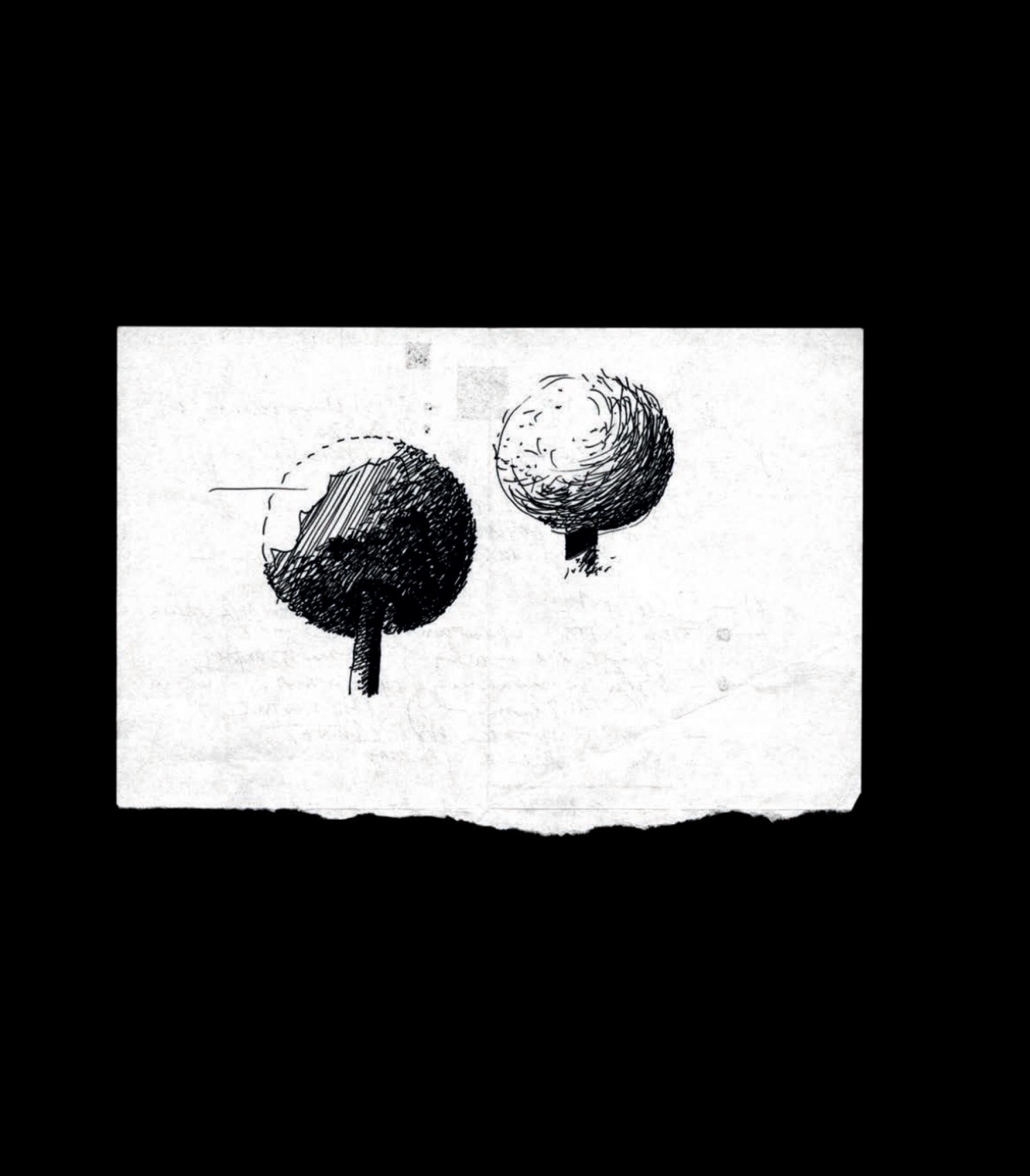

At the turn of the century, Spasoje Krunić added two more gems to the treasury of human history: first, the internationally famous Memorial Ravna Gora (1998-2000), where he experimented with minimalism in an expressive landscape, and Motel Koral in Arilje (2003-2012), where he goes back to (romantic) expressionism, thus confirming his authenticity that he has skillfully built and developed since his youth. In my opinion, special attention in Spasoje Krunić’s oeuvre should be given to his metaphors from sacred architecture and primarily his drawings.

These metaphors tell us mostly about his relationship to the world and life, emanating modesty and restraint, a kind of nobility and humanity, leaving behind only indifference to differences – pure truth. Thus he uses, in the same remarkable way, my favourite metaphor of the Great mosque in Baghdad - First Prize on international competition (1989), and the metaphor of the temple of Christ the Saviour in Priština (1991-1999), where works were suspended after Serbia had lost jurisdiction over Kosovo and Metohija.

Spasoje Krunić never stopped working on what has not been completed, because his discipline, dedication and ethics did not allow. Indeed, as a dedicated modernist oriented towards a revolution in thinking, he has always been free-for-something, knowing that it is the only way to be free-from-something, which gave him, over and over again, the possibilityand motivation to continue down the road that few people would dare to take.

Prison for Foreigners in Belgrade (1983).

The worlds of Spasoje Krunić’s metaphors, in my view, demonstrate this profoundly and prove him to be an accomplished creator of pure thought. These and such worlds are nothing but infinite relations of elements of his personal world with the elements of identity groups he has been involved in, and above all with the elements of the world of history of humanity, nature and the universe.

Popović Tombstone (2003).

I know very well that the question of immortality of a human being is something beyond nihilism and sacrifice, and that it is promised only to those who think and act positively, in a word – to creators. Spasoje Krunić was undoubtedly one of the major creators who enriched the world of human history and the world of architecture. His combative and uncompromising defence of the world of architecture and his commitment to affirmative dialectics never cease to amaze me.

—

by Aleksandar Bobić On Metaphors of Architect Spasoje Krunić from the afterward of the book “Spasoje Krunić: Spatial Metaphors” (2017)