Pioneer Architects VII

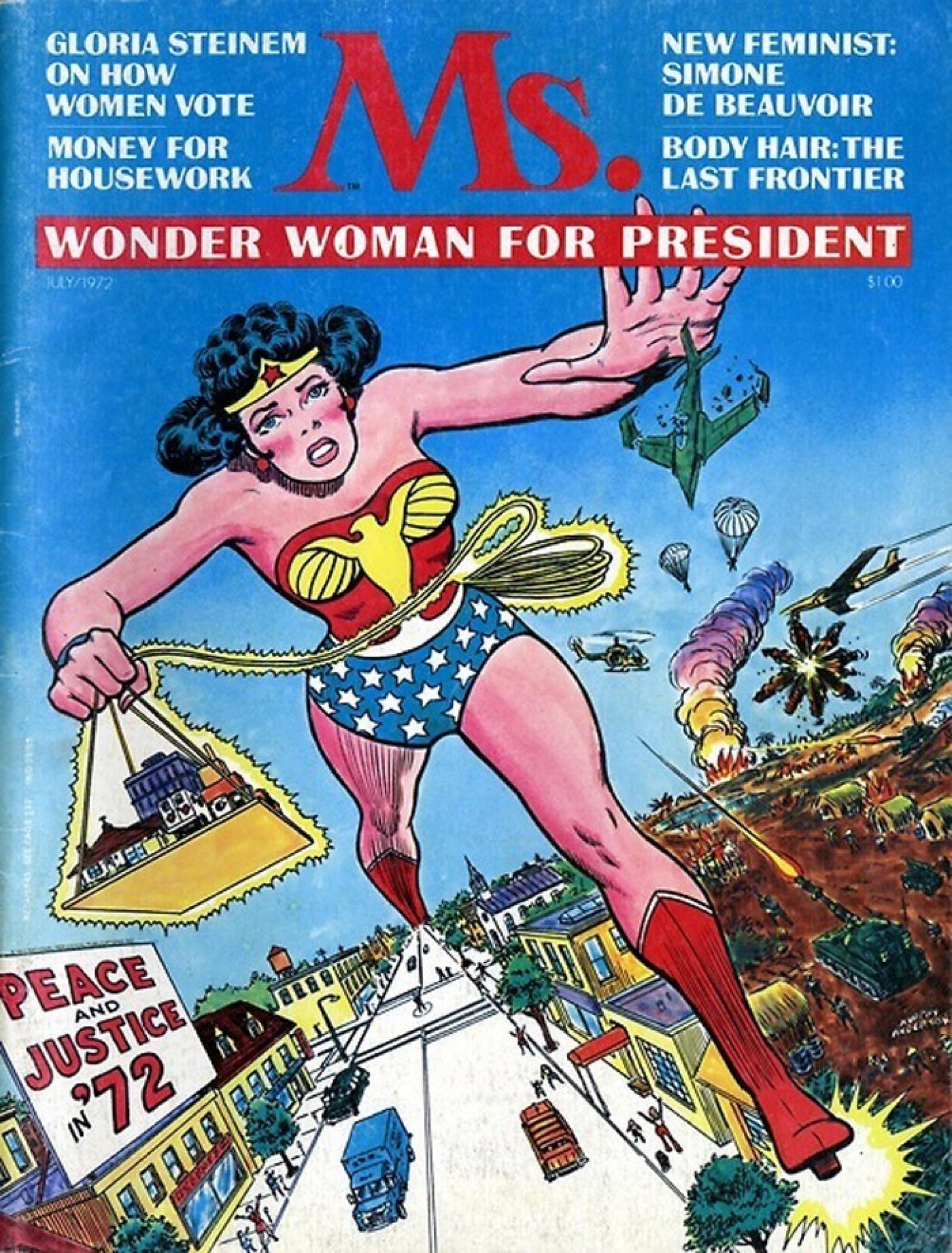

In July 1972 a Ms. magazine issue made its debut as a monthly magazine for feminists with a full-color illustration on the cover promoting Wonder Woman for President. It presented women as doctors, lawyers, judges, brokers, economists, scientists, political candidates, professors, company presidents.

None of women was presented as architect, although they were very present in architects profession in 1972. They were creating feminist spatial practices and redefining American architecture with fights for gender equality.

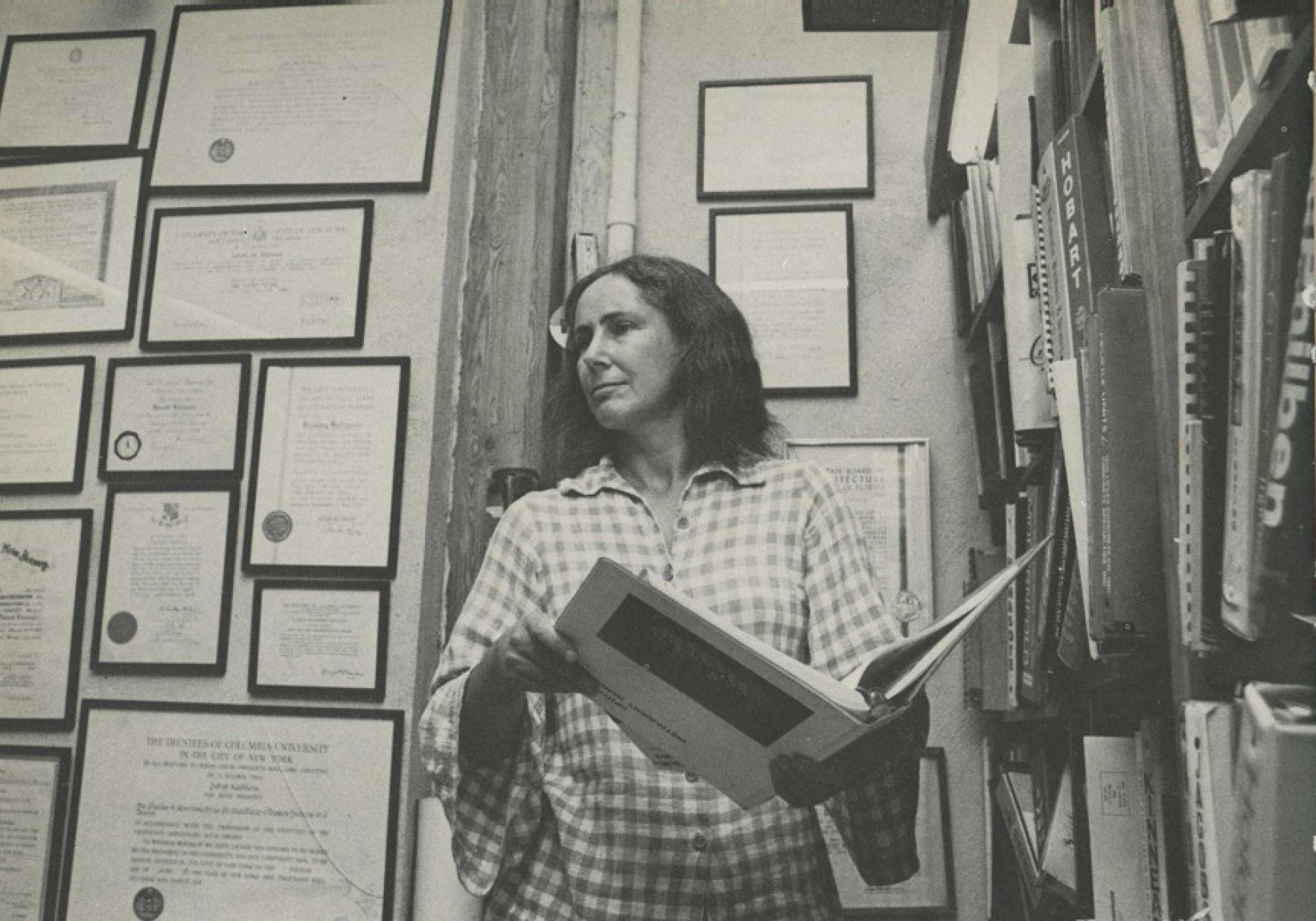

One of such architects was Judith Deena Edelman, known as Dagon Lady at AIA headquarters. As she struggled to find work after graduation and was rejected by numerous employers that they would not hire women as architect, she became an advocate for the advancement of women in architecture.

Edelman was first woman that lead the AIA’s in 1972. | Photo via Eskwblog

Edelman was a frequent campaigner for the advancement of women architects and insisted that women should become involved in the American Institute of Architects although it was an exclusive gentleman’s club. She founded an organization to promote the advancement of women architects Alliance of Women in Architecture in 1972.

Another innovator in architecture, Eleanor Raymond, explored the use of innovative materials and building systems. She designed one of the first solar-heated buildings the Sun House (1948), which was her most ambitious and innovative house with solar collectors. It was developed together with Dr. Mária Telkes from the MIT Solar Laboratory.

Raymond (right) with Maria Telkes in front of Sun House. | Photo by Courtesy of the Frances Loeb Library, Harvard University Graduate School of Design.

Raymond took part in a number of social movements of her day, including the women’s suffrage movement and the settlement house movement. It was through a suffragist organization that she met her life partner, Ethel B. Power. Raymond and Power became a longtime editor for House Beautiful magazine.

Among the eight cofounders of The Architects Collaborative (TAC) in Cambridge, Massachusetts were Sarah Harkness and Jean Fletcher. Two women among five young architects formed the firm with Walter Gropius in 1945. Both were inspirational figures for women in architecture of that time.

The Architects Collaborative (TAC) founding members from left to right: Robert S. McMillan (1916-2001), Norman C. Fletcher (1917-2007), Benjamin Thompson (1918-2002), Louis A. McMillen (1916-1998), John C. Harkness (1916-2016), Jean B. Fletcher (1915-1965), Walter Gropius (1883-1969), Sarah Harkness (1914-2013).

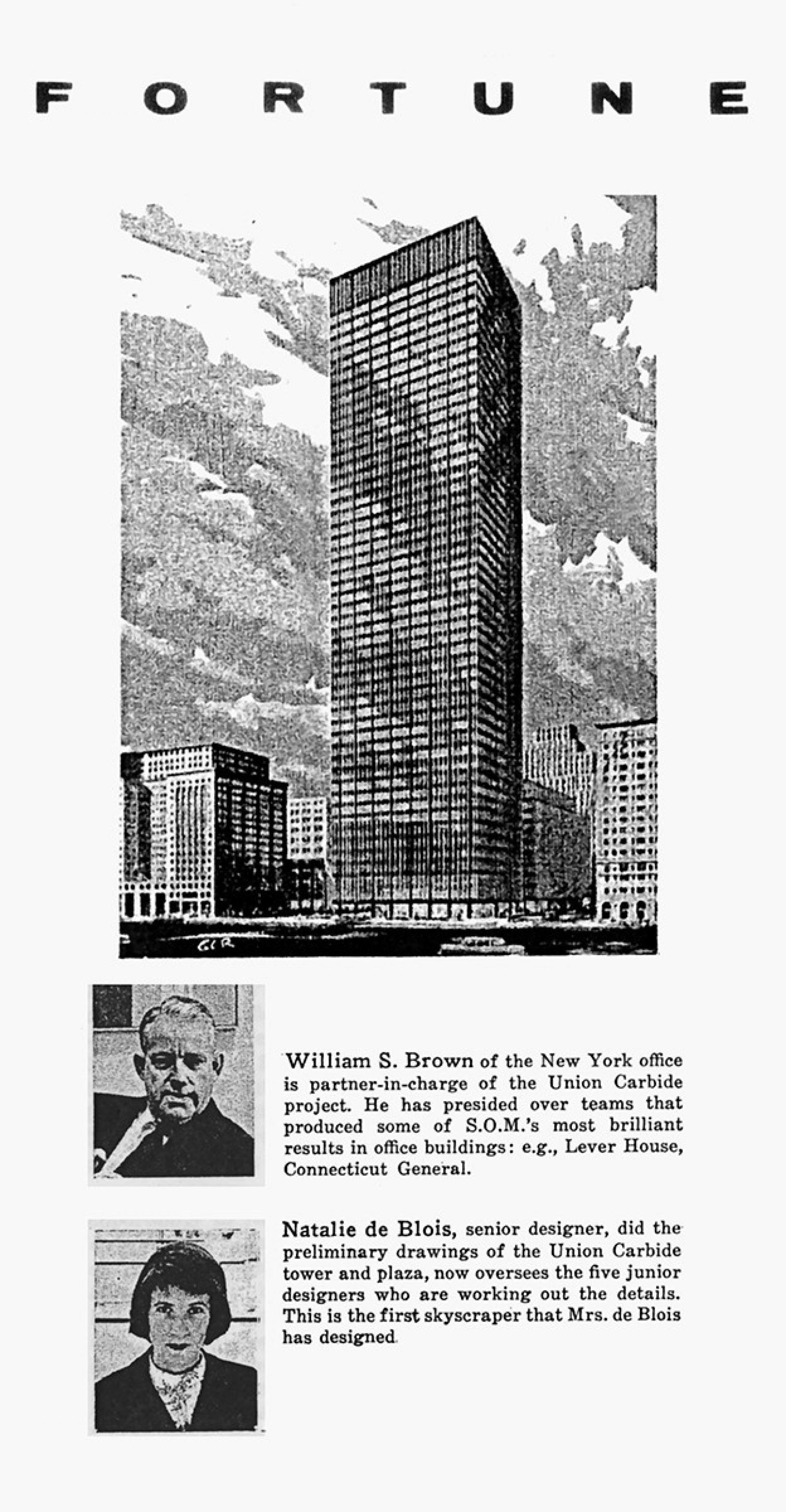

A know pioneer in the male-dominated world of architecture was Natalie de Blois already in 1940s. She was a partner of Skidmore, Owings and Merrill but was evident that Gordon Bunshaft took all the credit and she did all the work.

Entrance of the Union Carbide Building on Park Avenue by Natalie de Blois in the heart of New York City. | Photo by © Ezra Stoller | Esto

As part of SOM company was transferred in Chicago she worked there constructing skyscrapers from 1962 to 1974. In Chicago she founded the Chicago Women in Architecture. Natalie was almost invisible in her own day, but she helped guide the design of three of the most important corporate landmarks of the 1950s and ‘60s: the headquarters of Lever Brothers, Pepsi-Cola and Union Carbide. At that point, there were only five or six women across the U.S. who had a substantial architectural practice and Natalie was doing buildings in the heart of Manhattan.

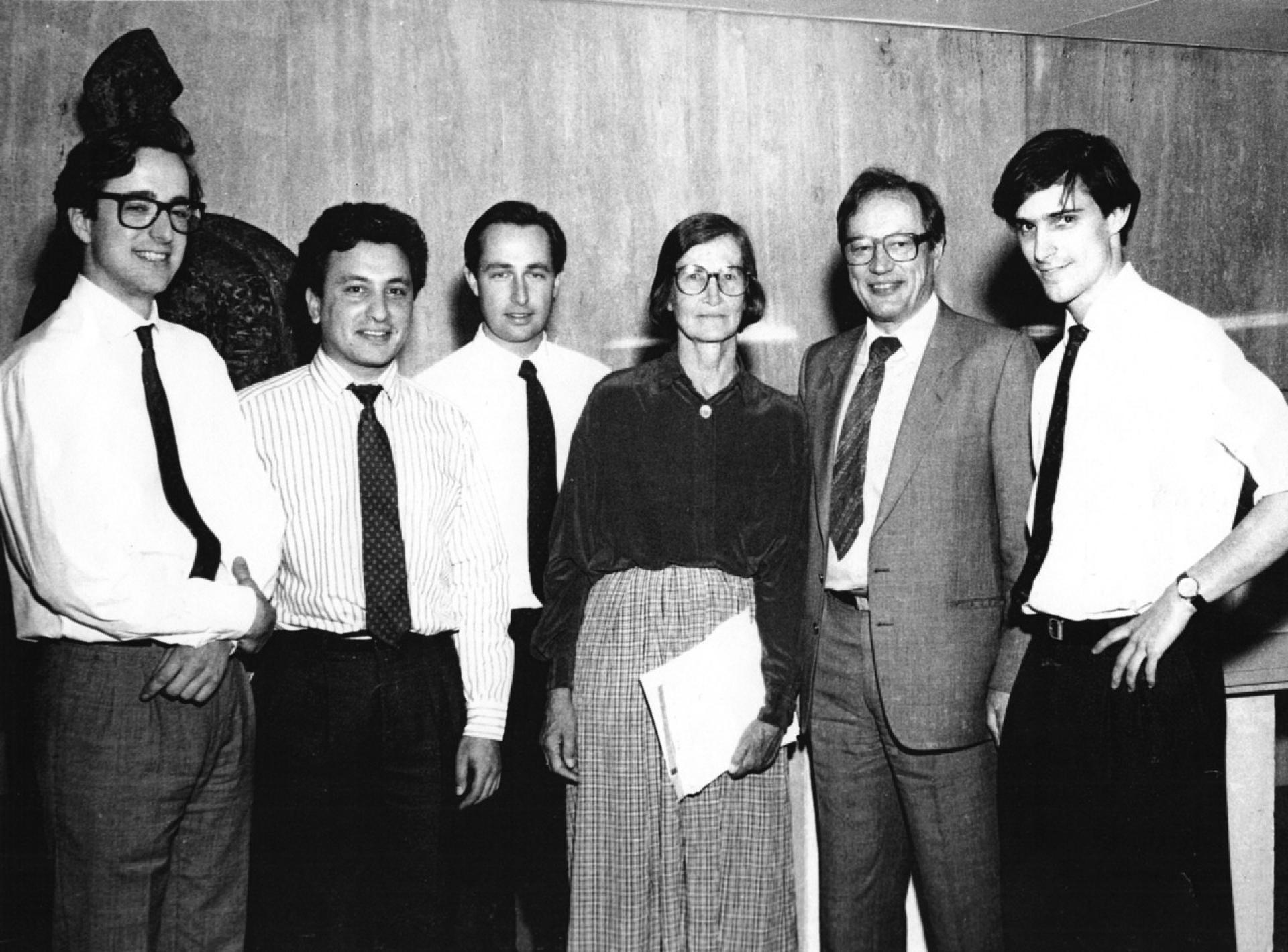

Natalie de Blois with former students (1988) at the New York offices of SOM. | Photo Courtesy Natalie de Blois

The AIA had been open to women since 1886, when Louise Blanchard Bethune became its first woman member. One percent of AIA members were women by the 1970s (250 of 25,000). Natalie de Blois, who claimed to have never felt overt sexism during her career as a senior designer with SOM, recalled the satisfaction of “getting together with like-minded women, and supporting them in whatever way we could” through Chicago Women in Architecture. The Places columnist Gabrielle Esperdy writes how such possibilities helped create contact with other women practitioners in the professional isolation of the time that helped “stop feeling like a freak” for being an architect.

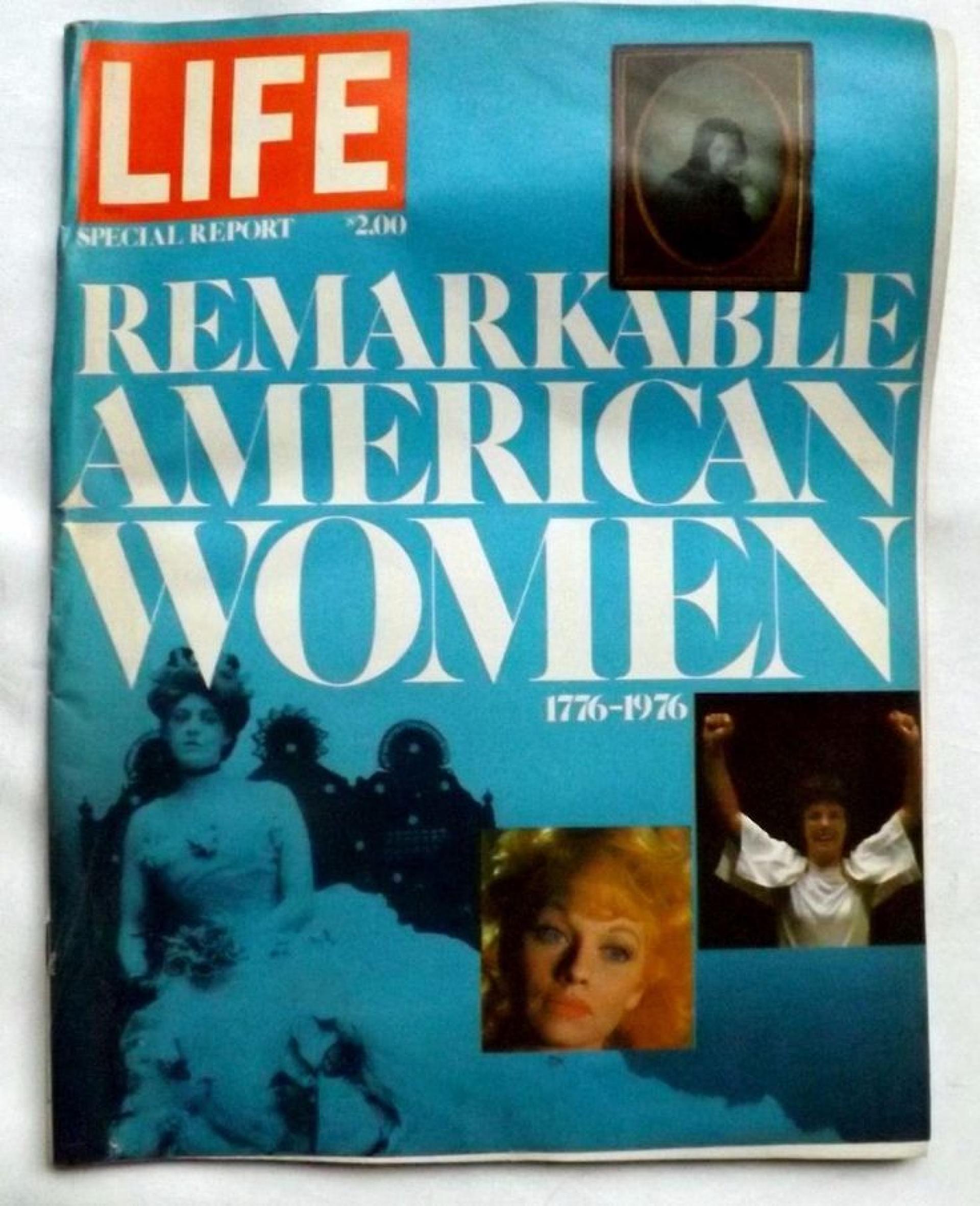

Special Report of Life: Remarkable American Women (1976) where Julia Morgan is the only architect mentioned.