FOMA 23: German Post-War Modern

As a result of the devastating destructions of the Second World War architects in postwar Germany were faced not only with the rebuilding of cities but also with the opportunity to break with the past and follow new paths.

Children in bombed out Berlin in 1945. | Photo Otto Donath via Berliner Ferlag

The following five buildings represent Forgotten Masterpieces of German postwar architecture that deserve a closer examination.

The theater captured shortly after its completion in 1966 by Sigrid Neubert. | Photo via Baunetz

The first building is the Municipal Theater in Ingolstadt by Hardt-Waltherr Hämer and his wife Marie-Brigitte Hämer. Hämer is best known for his Berlin works, where he eloquently proposed a cautious renewal of the city and its quarters.

Interior view of the theater around 2009. | Photo via Breitschaft Architekten

The theater, designed and built between 1960 and 1966, is undoubtedly a prime example of German Brutalism that takes a bold modern stand within the city center of Ingolstadt: with its board-marked concrete surfaces and complex, interlocking interiors makes for interesting spatial experiences that are faintly reminiscent of Hans Scharoun‘s Berlin Philharmony.

View of the church from Northwest. | Photo by © Florian Monheim

As the followers of my Tumblr might have recognized I have a major knack for postwar church architecture in Germany and beyond. One of the most interesting examples of postwar modern church architecture in Germany is St. Paulus in Neuss in the lower Rhine region, a congenial collaboration between architects Fritz and Christian Schaller and engineer Stefan Poloyni.

View from East into the nave. | Photo by © Florian Monheim

On a hexagonal plan they created an awe-awaking space that is crowned by a spherical, folded and diamond-shaped vault. The church quintessentially represents the inventiveness of architects faced with the task of designing contemporary religious architecture: a spectacular, technologically innovative space that relies on the interplay of light and shadow to create a contemplative yet solemn atmosphere.

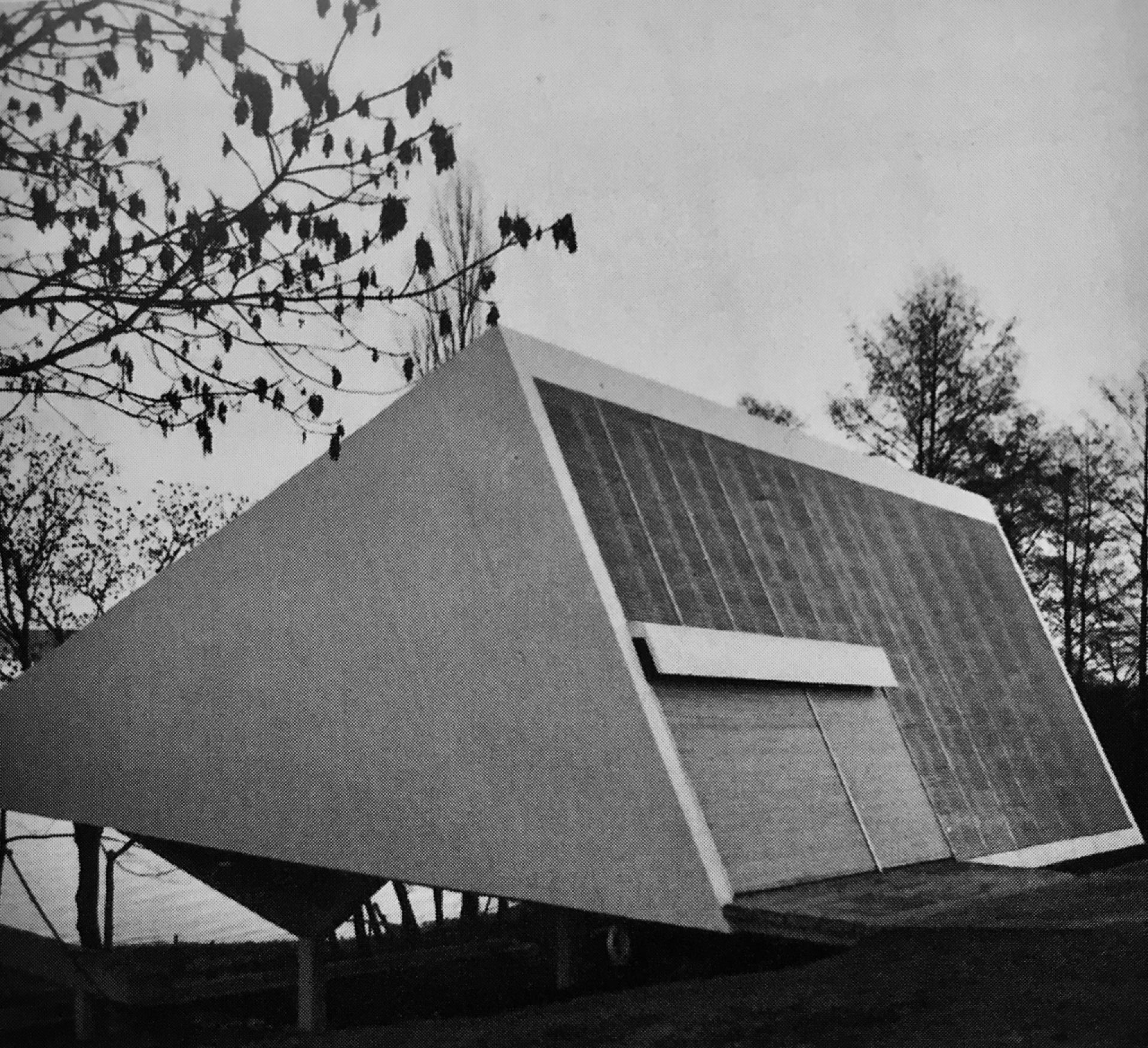

Moroshito after completion in 1961. | Photo via SAII

The summer house Moroshito, which Paul Stohrer designed for himself at Lake Constance, is a very unusual example of German postwar modernism and as such a favorite of mine. In its wedge-shaped design Stohrer processed influences from Oscar Niemeyer, a reference rarely present in German postwar architecture, and also gave expression to his colorful personality, which not only included a life-long passion for painting, but also for flamboyant sports cars.

The house’s little bridge leading to the waters of Lake Constance. | Photo via Ruppenstein

Free from a client’s restriction Stohrer realized a house that was tailor made to his needs and gave him the freedom to play with shapes, materials and plans.

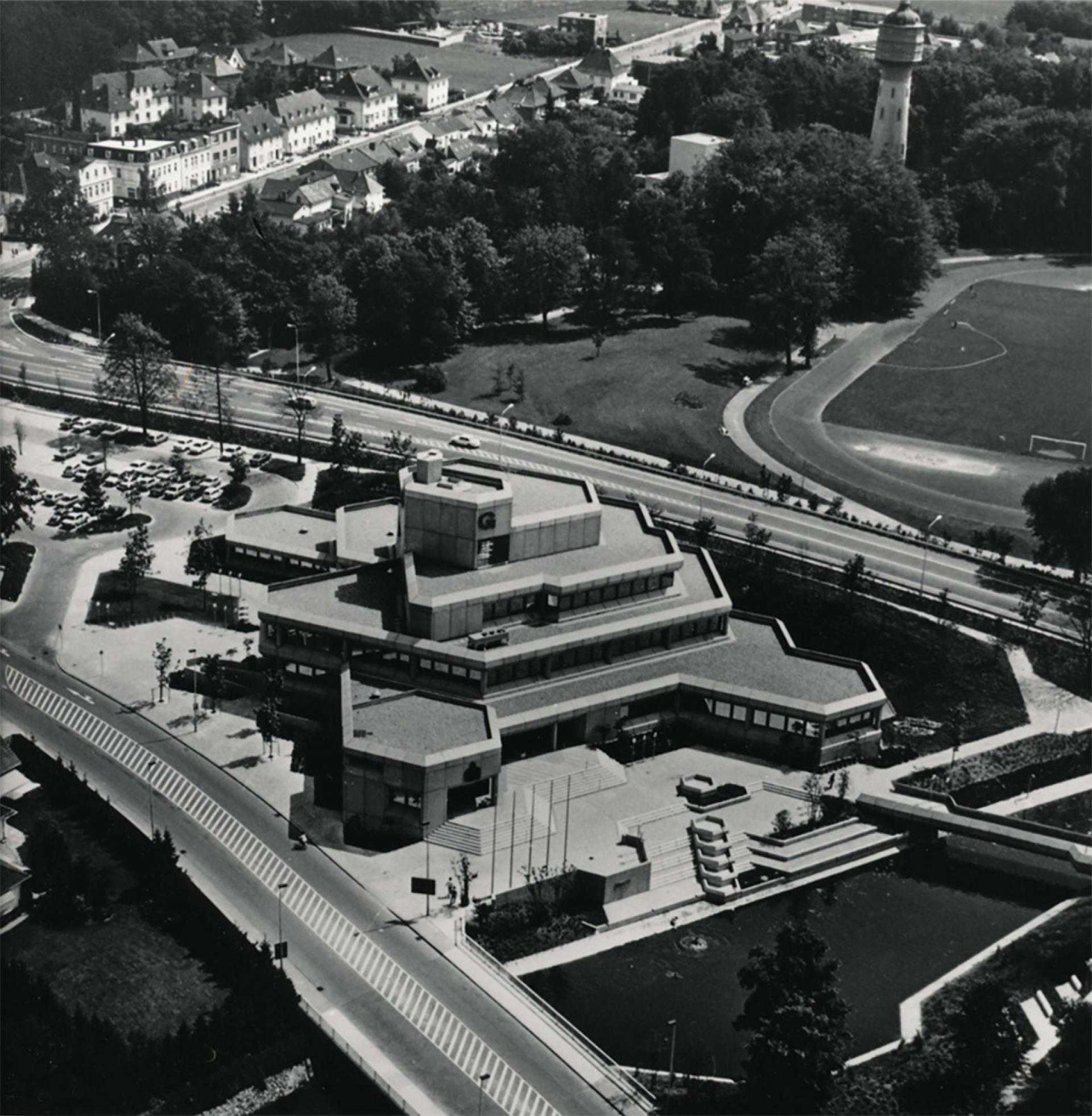

Aerial view of the town hall in 1975. | Photo via Baunetz

Harald Deilmann’s design for the Town Hall Gronau, a city on the German-Dutch border, represents a multi-functional approach to town halls in Germany in the 1960s and 1970s.

The town hall in 2016. | Photo by © Christian Richters

The scaled design houses a multitude of rooms, office, meeting places and with its raw concrete facade gives expression to the increased artistic freedom architects sought in these years. The building ranks among the most interesting yet overlooked examples of brutalism town hall architecture in Germany after WWII.

The Stadthalle in c. 1964. | Photo via Wesser Kurier

Last example of the architectural self-confidence of cities in postwar Germany is the Stadthalle in Bremen by Roland Rainer, built between 1961 and 1964. Rainer’s idea was to form a structural unity of a roof and stands, an idea that resulted in a suspension roof spanning more than 100 meters.

The Stadthalle was in 2000 renamed to AWD Arena. | Photo via Ortsamtwest

Due to the resulting expressive construction the Stadthalle soon became one of the city’s landmarks and together with the Stadthalle in Vienna and the one in Ludwigshafen forms a trilogy of Rainer’s successful civil engineering works.

Phillip Ost studies art history at Westfälische Wilhelms-Universität Münster, a middle-sized town in the Northwest of Germany. He focuses on postwar art and architecture in Germany and beyond with a special emphasis on postwar church architecture and German Art Informel. In 2014 he established German Post-War Modern, initially intended to serve as his personal visual archive of largely forgotten modernist architecture in Germany.