New Belgrade Contradictions

Although the process of urbanization of the marshland between the rivers Sava and Danube started before the second World War and the first modern constructions appeared before socialism, it was the period of socialist urban modernization after WWII that was the longest and the most intensive, that created the New Belgrade urban presence.

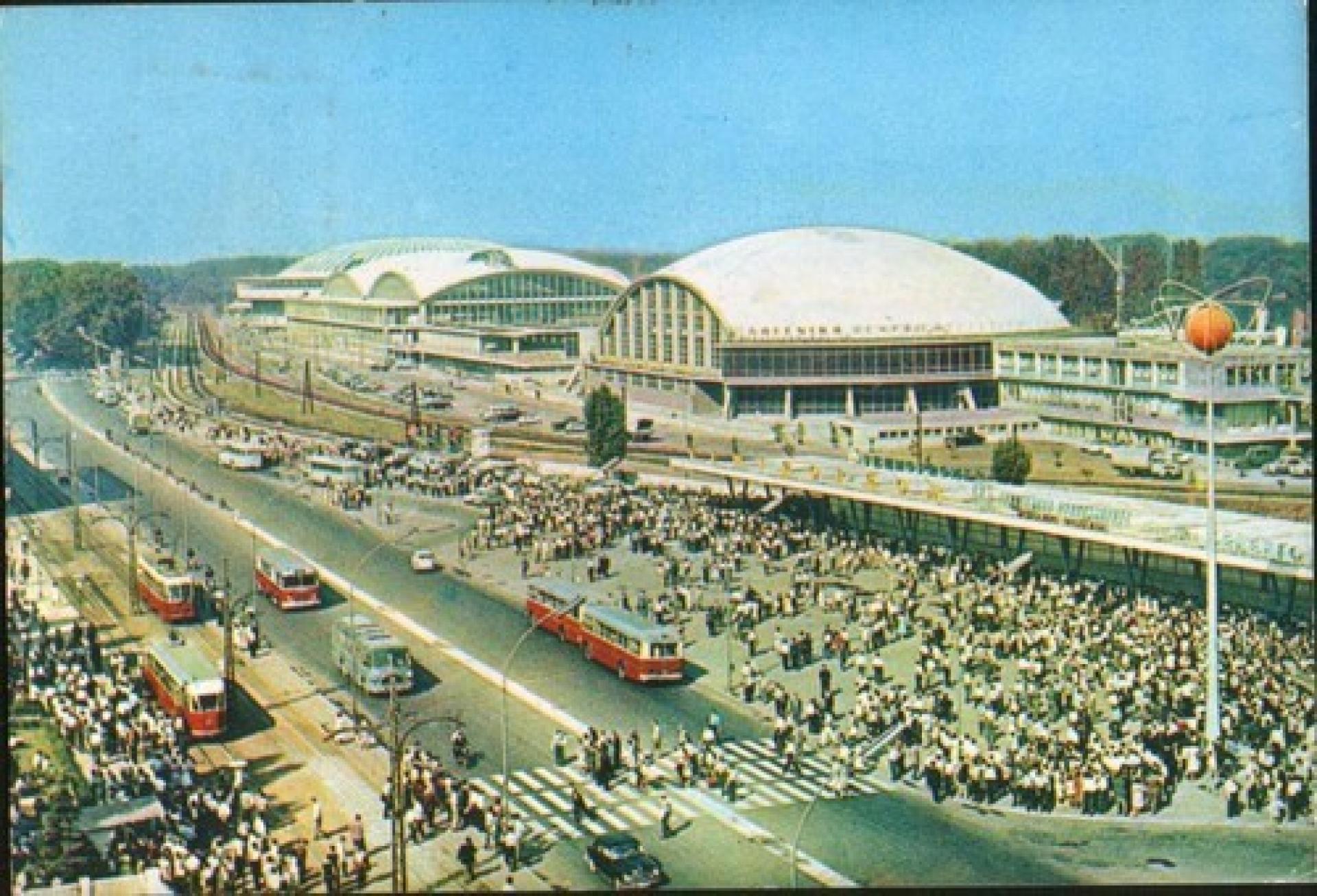

Belgrade Fair complex by Milorad Pantović is one of the most significant achievements of the Serbian post-war architecture | Photo from the book Beogradski sajam, Mišić (2006).

New Belgrade was developed from the scratch in an environment of continual social reforms that were following the progression of political imagination in the socialist Yugoslavia.

The project for the new city underwent major revisions following the pace of political experimentation in socialist Yugoslavia, for instance, between the late 40s and the early 50s, when questions of state representation were explored through the designs for the capital city, and in the 60s and 70s, when priorities shifted to an expression of egalitarian values through public housing. In the 80s and 90s the expected reaction to modern urbanism has been summed up in postmodernist cliches, and over the past two decades, when the radical abandonment of New Belgrade as a modernist urban vision occurring in tandem with the breakdown of the socialist state and the uprising of neoliberal tendencies.

Serial of contradictory tendencies that characterized both socialist ambition to create collective environment and post-socialist market development with the inclination toward increasing singular interests, have created the unplanned discontinuity resulting as heterogeneous structure of New Belgrade unlikely to the uniformity of modernist cities worldwide. Although permanently planned, New Belgrade reached unplanned inconsistency becoming a territory of contradictory sequences made by interrupted attempts to achieve comprehensive urbanity.

FIAT building by Milan Zloković was created at the time of the full impact of a totalitarian ideology for the Italian industrial giant.

Sequence 1

The location that was chosen for New Belgrade implies a radical break with the past, a political and spatial clean slate. Until 1918 this territory had the status of a borderline vacuum running along the marshy confluence of Sava river into Danube; it had thus remained vacant throughout the course of history. Positioned on higher ground and facing each other across the defensive valley, Ottoman Belgrade and Habsburg Zemun developed separately, albeit in proximity. The only significant trace of urban intervention at the site—augmenting its symbolic configuration—was the old Belgrade fairground on the left bank of the Sava, designed in the language of prewar modern classicism and opening in 1937 on the occasion of Belgrade’s first international exposition. In a tragic reversal, shortly after the start of World War II the complex was turned into a Gestapo-run concentration camp that was almost demolished by Alliance forces in their bombardment campaigns.

Sequence 2

Urban plan for New Belgrade submitted by Dobrović in 1948 illustrates the way in which the project for building the new city was tied to the ambition to create specifically socialist expression in architecture. Dobrović’s plan reinterprets functional zoning of housing, work, leisure, and traffic in a hierarchical “zoning” of governmental facilities focused on the Federation Palace. This contradiction between the plan’s form and its content derives from its dualistic design language, which drew on CIAM functionalism as well as the eclectic formalism of socialist realism. The political climate of the period may have contributed to this architectural dualism. With Tito and the rest of the state leadership pursuing political independence from both the West and the Eastern Bloc in the late 40s, a development that would culminate in a crisis in relations between Yugoslavia and the USSR in 1948, straightforward allegiance to either of the dominant architectural paradigms may have been undesirable. Instead, a new model began to emerge, mixing elements of both sides into a particularly Yugoslav form of what has been termed “socialist modernism” in architecture.

General Staff by Nikola Dobrović accommodated Yugoslavia’s Secretariat for National Defense. The complex was conceived as an ensemble composed of two monumental blocks creating a city-locked symbol of the city gate. | Photo via Beobuild

Sequence 3

The economic and political crisis sparked by Yugoslavia’s break with the Eastern Bloc temporarily halted all construction and much of the planning activity during fifties. The self-management model of organizing the economic system with “social ownership” and management entrusted to the workers in each enterprise, extended beyond the economic sphere to take in education, culture, social welfare, public health, political administration, and territorial organization.Under these circumstances, New Belgrade was approached afresh, freed of much of the ballast of state representation and with a clear intent to construct a socialist city—in particular through public housing. As a social program, housing was defined in ideological terms, too: it constituted a public good comparable to green areas or infrastructure, with the state acting as a guarantor of equal access to housing for all its citizens and the guardian of the principle of social justice. In what looks like a contradictory move, the Yugoslav government also promoted economic liberalization and sought to achieve higher living standards by permitting a form of state-controlled market economy in which public housing construction figured as a catalyst for economic growth and industrialization.

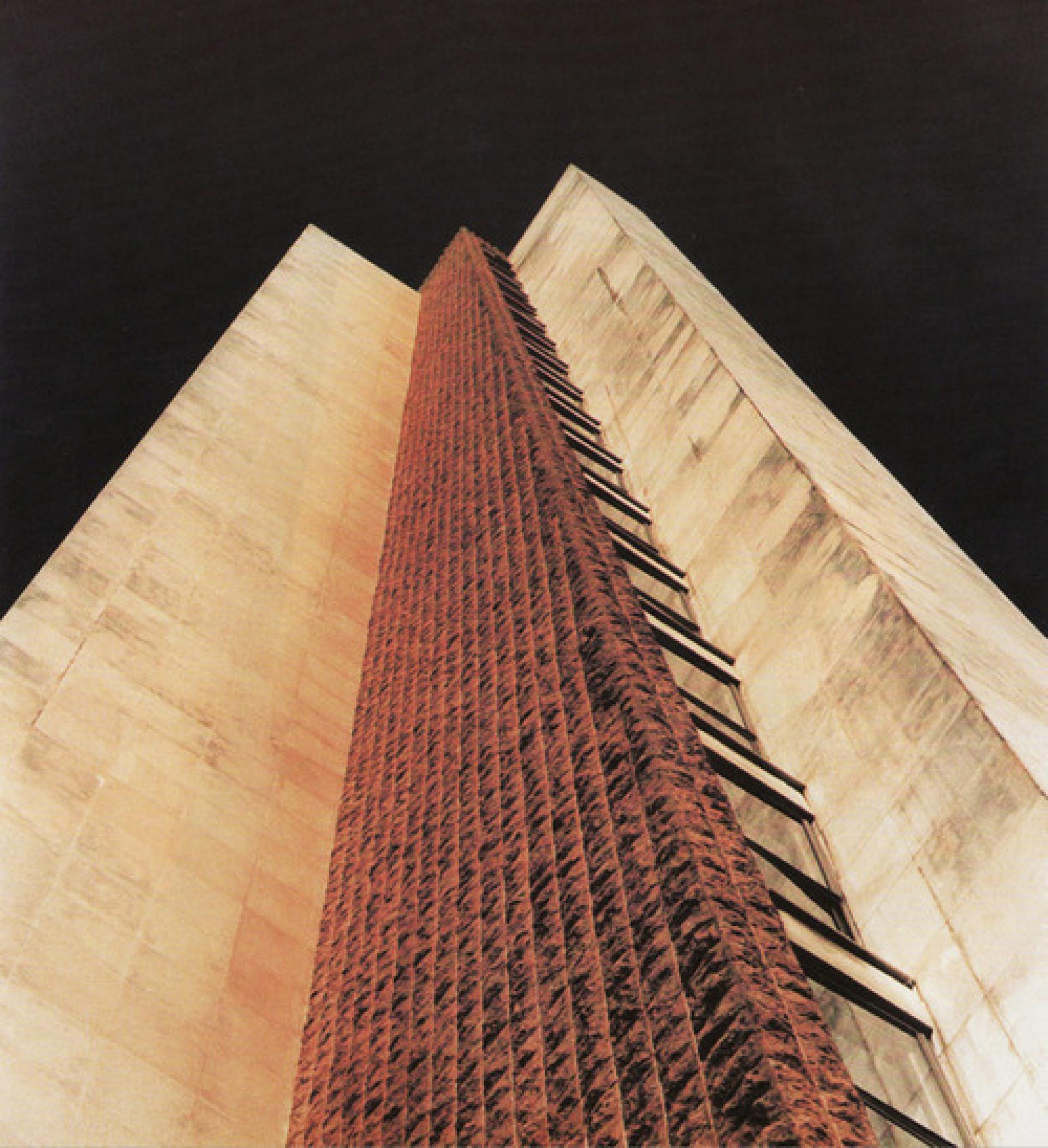

Social Security Building by Aleksej Brkić is purified by pure logic of geometry. | Photo by private collection of Lijlana Miletić Abramovič

Sequence 4

New Belgrade’s social vision in the sixties was tied to the self-management concept, in which communities would engage in improving their daily life and their surroundings, together with the municipal administration. On a micro-level, self-management took the form of house councils for each apartment building. At the next level, a local community or neighborhood unit was defined as the city’s principal self-management body. The idea of community was thus linked to spatial proximity; in New Belgrade neighborhood units coincided with blocks, each with locally elected self-governing organs. The blocks’ scale was linked to the value of collectivity, which was further articulated in the unusually careful design of public amenities and open spaces, including artificial topography, landscaping, and public art arranged around inter-crossing pedestrian promenades inscribed into the center of each block. The public infrastructure included kindergartens, primary schools, playgrounds, parks, medical facilities, supermarkets, stores, craftsmen’s shops, and so forth. There was also emphasis on spaces for cultural, social, and political gatherings and work—clubs, libraries, assembly halls. In each block, these services were assembled in a small complex, the local community center, an attractive building typology within housing production that offered leeway for architectural experiments. However, the conceptual imbalance in the planning of public amenities for the new blocks was aggravated by lengthy construction periods, long delays and lack of financial resources. The priority to provide large number of apartments typically led to situations where the completion of commercial and cultural spaces, or even of adequate public transport, was extensively, sometimes indefinitely, postponed. During the period of its realization New Belgrade gradually decayed into an eternal building site.

Sequence 5

The changes in Yugoslav constitution from the seventies, and the proceeding legal system that was introducing independent business actors supported by the newly established investment banks, effected an immense transformation in socialist urban development. This transformation produced an effective monopoly held by a few formerly state-owned, now socially run corporations. Following constitutional changes, the influence of construction companies on the urban development of New Belgrade has been enhanced, mainly owing to the right to use land awarded by the state. This practice meant that effectively the urban planning and urban development processes have been placed under the control of the construction companies. Their impact was manifesting not only in the appropriation of urban space and increasing social disparities, but also in the creation of a professional environment rendering urban planning superfluous while promoting insular corporate architecture and urbanism as a professional standard. The courses of urban development of New Belgrade gradually were making way for more fragmented procedures that continued to focus on individual buildings rather than on urban space and the city. By favoring their particular interest, socialist construction companies were developing fragments rather than totality.

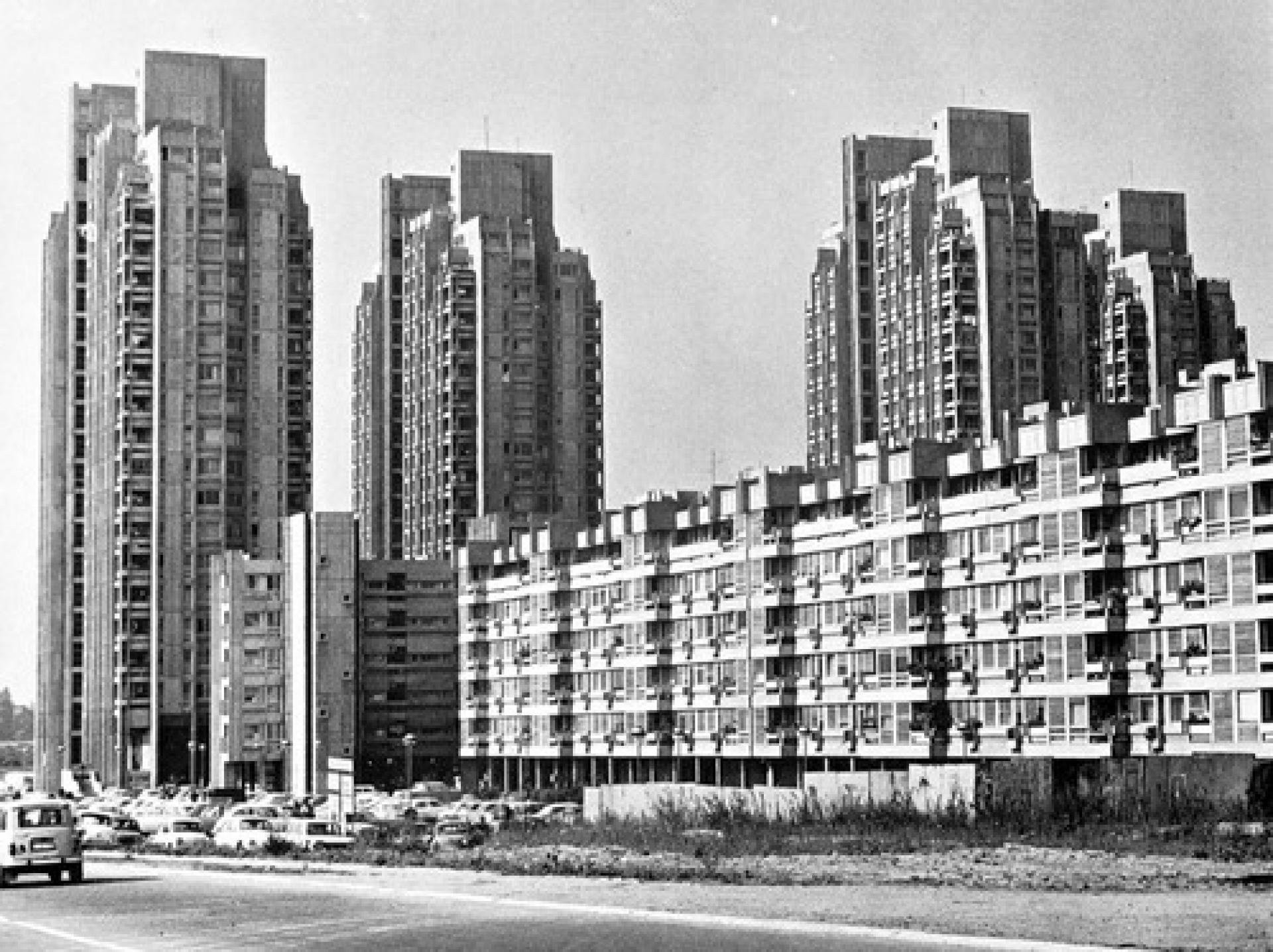

Residential Complex Block 23 by Aleksandar Stjepanović, Božidar Janković and Branislav Karadžić is an expressive project in New Belgrade | Photo from Arhitektura i urbanizam, IAUS

Sequence 6

A few years after Tito’s death, in the mid-eighties, the untouchable aura of New Belgrade’s central axis broke down, its gradual colonization beginning from the far end and proceeding toward the Federation Palace, approaching it slowly and hesitantly as if a thorny subject or a daunting task. The most ambitious proposal was a “Study for the Reconstruction of the Central Part of New Belgrade and the Sava Amphitheater,” by the Town Planning Institute team lead by Miloš Perović. Starting with the now widely established anti-functionalist critique, which among other things attacked the inflexibility of the block concept, the lack of argument or articulation of large green surfaces, the uniformity of urban space, and the social and economic problems caused by the separation of urban functions, Perović went on to argue that in New Belgrade static planning procedures and exaggeratedly large open spaces and buildings led to the loss of the human scale and hence to a space without vitality that, ultimately, was unable to attract and catalyze positive development processes. He identified a possible framework for a different, “natural,” socially and economically viable process of urban development in the “lessons of the past” and a return to traditional urban forms. The effect of this and similar criticism was less pastoral than far-reaching in that it furnished a pragmatic rationale and formal idiom for the market economy that was to unfold in the near future. What was built in the end was a stark contrast to romantic vision. In the 80s, the fragments of the functionalist city were merely juxtaposed with equally vulnerable and incongruous fragments of a traditionalist city.

Naftagas Building by Keković, Županjac and Pantić. | Photo via Novisad

Sequence 7

At the start of the nineties along the modern boulevards and tramlines of New Belgrade, the trading of smuggled goods emerged as metaphors of the city’s political, economic, and social collapse. The chaotic situation in which grey economy and legal breakdown blended with political opportunism was kept in balance through social entropy. Informal operations did little to alter New Belgrade physically; instead, volatile influences were adapted solely through the changing forms of occupation of the city’s physical body. New Belgrade’s unfinished network of public amenities was overhauled, with the functions of the abandoned local centers resurfacing in informal spaces, common rooms, or apartments; kiosk clusters sprang up at the foot of the apartment blocks, with offers extending from real-estate agencies and dental practices to gyms and fortune-tellers. The New Belgrade’s blocks seemed simply to absorb all the turmoil the city experienced, from anarchy and a “flexible” economy to transnational migration—all volatility pacified, settled, contained within a robust urban form.

Yugoslav Drama Theater by Dejan Miljković, Zoran Radojčić was burned to the ground on October 17th, 1997 due to an error in the installation. | Photo via dejanmiljkovic

Sequence 8

The conclusive efforts to reshape the character of New Belgrade belong to the period of post-socialist transition after 2000. The Master plan of Belgrade 2021 done by the Town Planning Institute designated New Belgrade a top-priority zone in the planned expansion into a commercial hub: the idea was that its high-quality infrastructure and large residential community would attract the private investment. Marked by the rising influence of private lobbies, the present urbanistic ethos has again found its most acute and revealing expression in the space of the New Belgrade’s, never completed central zone. The main actors involved in projects at this site have been private interest clusters formed during the 1990s, many of which are direct successors of the former socialist elites. While benefiting from political nepotism and generous public funding, they have shown no sense of commitment to New Belgrade’s urbanistic premises. Even at such sites as the city central zone, the agenda for new architecture and urban representation followed the ideology of market democracy that favors economic viability and the primacy of deregulation. Among the early examples of this process, belong the series of iconic mega-developments proposed for the most expensive building parcel in the city and also the last large plot in New Belgrade’s central zone, Block 26 directly facing the Federation Palace. They all represent local variants of a typically neoliberal development process, which relies on maximum public facilitation (public land, public funding, procedural shortcuts) combined with maximum private control over the process (programming, site design, site development) and ultimately, over access to urban space. Paradoxically, the later model does not operate independently of its predecessor; rather, the precondition for the success of post-socialist neoliberal development is, essentially, the modern city’s existing technical and social infrastructure, upon which the new system parasitizes.

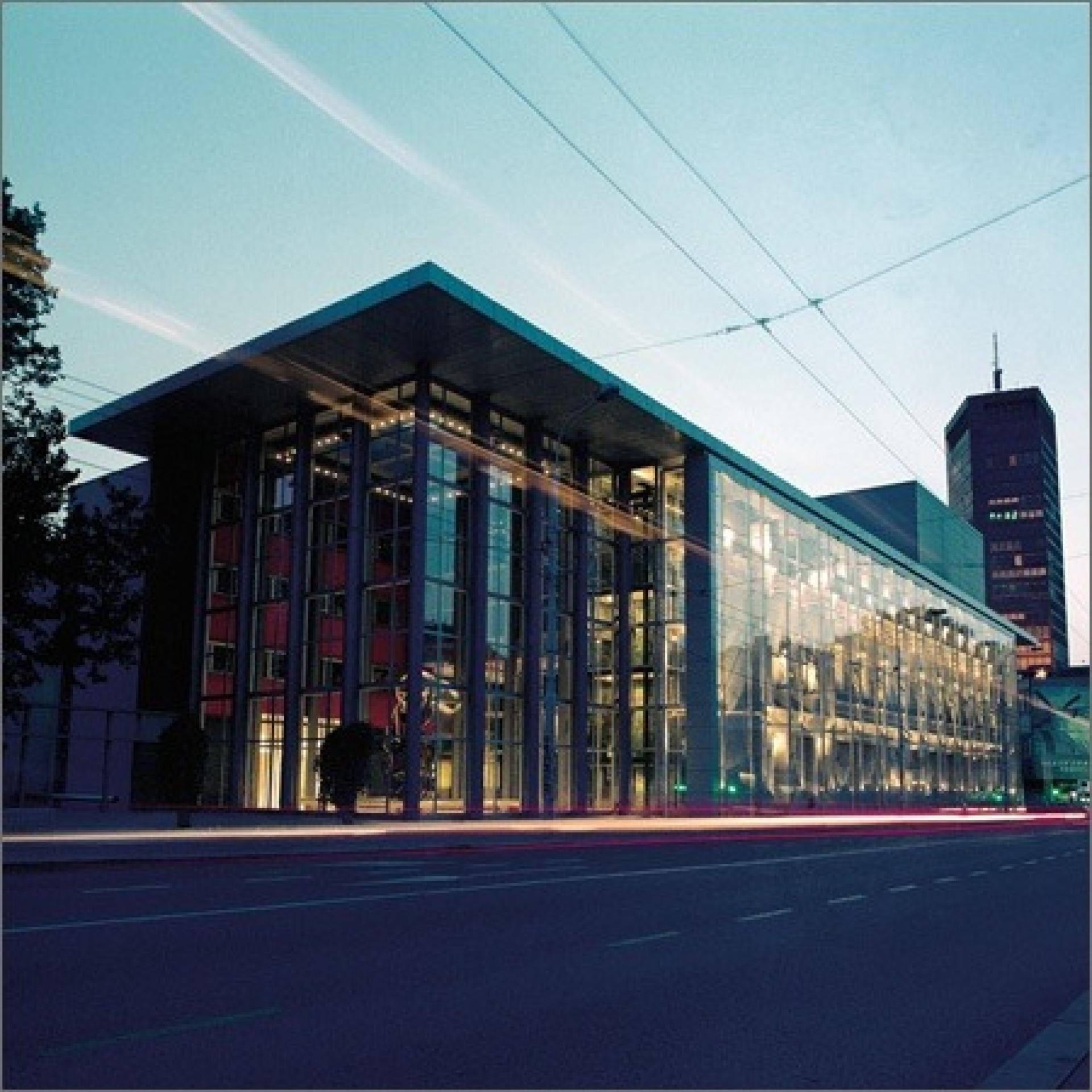

Zora Palace by Spasoje Krunić plays a key role in re-establishing a cohesive cityscape. | Photo via designed

Sequence 9

In neoliberal type of urban development practice, political instruments are used to establish private economic agendas. The hierarchy in this process of investment-centered decision-making begins with the private investor and moves down to the politician, then to the planner, for the sake of acquiring a planning amendment and the building license. In other words, private interest dominates urban development while politicians have the greatest influence on its planning. In this situation, Belgrade’s urban planning and architecture have followed a process of indiscriminate privatization and marketization; losing their critical role in the city, they have lost the city as the constitutive subject and purpose of their profession. New Belgrade thus underwent a radical, paradigmatic reversal: from a space shaped by the socialist state as a focus of political interest to a space shaped by private economic interests; and from a planned city to a city where no urbanistic concepts are required. At the same time, the architects found themselves demoted from visionary leaders to marginal figures. It seems inevitable that, instead of passivity and disillusionment, Belgrade’s architects and urbanists need to explore the radical potential of this new role, becoming active and critical voices within the city. In this role they no longer would serve as an extension of private investitures and state institutions but necessarily move into the public sphere—a sphere in which the motivation and support for the transformation of architectural practice and its vital engagement with the city could be generated and sustained.

Edited by Ivan Kucina based on the text Instability of Formal by Milica Topalovic, Belgrade Formal Informal, ETH 2012.

Serbia Unfinished, on May 9th, 18.00 at the Museum of Applied Art (MPU), Vuka Karadžića 18, Belgrade.

A presentation of three generations of Serbian architecture will be concluded by a public talk on the significance of these works for contemporary architecture in Serbia and abroad. Public talk will be organized in collaboration with the Museum of Applied Arts during the 36th Salon of Architecture. The selection of material will perform by the curators and the Council for the selection which will delegate by the Association of Belgrade Architects (DAB) in collaboration with the Architects’ Association of Serbia (UAS).

Participants

Milan Đurić, Aleksandru Vuja, Ivan Kucina and Ivan Rašković (all from DAB and UAS), moderated by Ljiljana Miletić-Abramović (MPU) and Boštjan Bugarič (Architectuul.)

Council for the selection: Vesna Cagić, Igor Marić, Ivan Rašković and Aleksandar Bobić/ The curators: Milan Đurić and Aleksandru Vuja.

Ljiljana Miletić-Abramović, an Art and Architecture Historian, Curator and Museum Adviser at the Department for Architecture and Acting Director of the Museum of Applied Art in Belgrade, graduated and received her master’s degree in the History of Arts at Faculty of Philosophy of the University of Belgrade with themes from Serbian Architecture of the 20th century. She has worked as a curator at the Department for Architecture of the Museum of Applied Art in Belgrade (since 2002) within which she manages and organizes the exhibition Salon of Architecture. She is the author of many scientific and professional papers in the field of architecture in recent times, amongst others the monographs: „Parallels and Contrasts – Modern Serbian Architecture 1980–2005“, Belgrade 2007 ( ISBN 978 – 86 - 7415 – 121-1) as well as „Belgrade Residential and Villa Architecture 1830 – 2000”, Belgrade 2002 (ISBN 80 – 7594 - 005 – X).

Ivan Rašković (1960) is associate professor at the Architecture Department of Belgrade Faculty of Architecture and a member of the AGM group (with Borislav Petrović and Nada Jelić). He is Head of classes at the study programs of the first and second years of Master degree and at the specialist programme of renewal of historic urban sites as well as the author of more than twenty buildings. He won six professional awards (Three Salon of Architecture awards, ‚‚Novosti‚‚ company award, Ranko Radovic Award, Triennial of Architecture in Nis Award etc.). He has 9 first, and twenty other prices won in various architectural competitions. All the references mentioned here are gained within the AGM group. He and Professor Borislav Petrovic have published monographic study TRADITION - TRANSITION/use of heritage in architecture. He is elected the National Commissioner of the Biennale of Architecture in Venice in 2014. year and the President of designers` sub/section (architects) of the Serbian Chamber of Engineers.

Ivan Kucina (1961) is an assistant professor at the School of Architecture, University of Belgrade, Serbia and a Visiting Professor at the School of Design Strategies, Parsons The New School for Design, New York, Polis University, Tirana, Albania, Singidunum University Faculty of Media and Communication , Belgrade and School of Architecture and Urban Planning, KTH Stockholm, Sweden. His research is focused on the informal building strategies and uncontrolled processes of transformation of urban structure of the Western Balkans. In bridging his research pursuits with his teaching, he has established collaborations with informal educational and research groups such as School of Missing Studies, New York and STEALTH group, Rotterdam. He published “15/3” (Univerzitet u Beogradu, Arhitektonski Fakultet, 2008) a textbook on the innovative methods of learning space-form dialectics within his Introduction to Architecture Design course. Ivan Kucina is a practicing architect and runs an interdisciplinary architectural and design practice together with architect Nenad Katic, with projects that range from urban design to residential buildings and exhibitions. In 2006, he co-founded the Belgrade International Architecture Week and currently serves as its Program Director and in 2012 he established the Urban Transformations program at Mikser festival.

Milan Djurić (1967) completed primary and secondary school in Belgrade. He graduated at The Faculty of Architecture, University of Belgrade in 1993, where has been working as a teaching assistant and teacher since 1994. In the middle of 2013 he was elected to the position of Associate Professor. Architectural researches are published in several monographs, written works and articles . Has been active in the field of the architectural practice since the mid 90 ’s of the XX century. Founded the architectural practice DVA Studio based in Belgrade with Aleksandru Vuja in 2000. He is the author, independently or as a part of the author teams, more than 50 projects. He has participated in a number of architectural competitions and has won over twenty awards, special awards , recognitions and purchases. Completed more than twenty buildings , of which the most important are : International passenger terminal on the Sava river in Belgrade (2005), logistic park Milšped in Stara Pazova (2005-2014), Vila Radović in Senjak, Belgrade (2010) and Kindergarten Tesla - Science for life in New Belgrade (2013).

Aleksandru Vuja (1963) works at the Faculty of Architecture, University of Belgrade, as an associate professor. He is the author of several publications dealing with architectural theory and research in architecture. Founded the architectural practice DVA Studio based in Belgrade with Milan Djurić in 2000. He has received numerous national and international awards and public recognitions for implemented buildings. The most important are Grand Prix of the Salon of Architecture in Belgrade ( 2014 ) , Salon of architecture awards in the category of Architecture (2000 and 2007), as well as awards in the competition Trimo Architectural Awards ( 2007, 2009 , 2011) for the design of industrial facilities.