Is It Possible To Exhibit Architecture?

A few years ago, I was asked by a group of experts surrounding an artist to curate a national pavilion during the Venice Biennial of Architecture.

I don’t remember exactly how the artist had been selected, but I’m sure it was on a democratic basis, and the people around him were all of great quality. Though, I had problems understanding what my role and curatorial tasks could exactly be, as the artist had already written a clear concept and produced detailed drawings for the forthcoming exhibition. My curriculum vitae had probably two interesting points to offer: as a foreigner I would have brought a nice touch of internationalism and, as an architect, a legitimation for an artist to participate to the architecture biennial. Though, being unable to define exactly my position and feeling not really essential, I refused that kind proposal and lost an opportunity to promote myself.

But the thing that annoyed me most was the questions lifted by the whole story. Why should an artist represent a country during the architecture biennial? Why should a curator be the last participant in such a project? Why, at a time when borders between disciplines are blurred, should we question the links between art and architecture? Each of these questions deserve at least a 300-pagethesis but they should always be in our mind when we visit the Venice Biennial. And I could also add: What is the exact role of an exhibition designer? What are the real powers at play in a time when public institutions are depending more and more from private founding? What does it mean to build temporary structures that will, afterward, only exist as images?

I might sound conservative but I think architecture is here to address social problems, to shape an idea of living and to enlighten its users and visitors. If, on top, in turns into stone the problems and culture of its time, it will become a masterpiece. But, instead of that, Venice gives us too often spatial experiences for VIPs by installing some kind of three-dimensional machinery that pretends to change their perception after two Campari-Spritz and a bunch of small talks (think about the cheap environmental questions, the pseudo-political engagement and the new-age philosophy that surrounds most of Ólafur Elíasson productions).

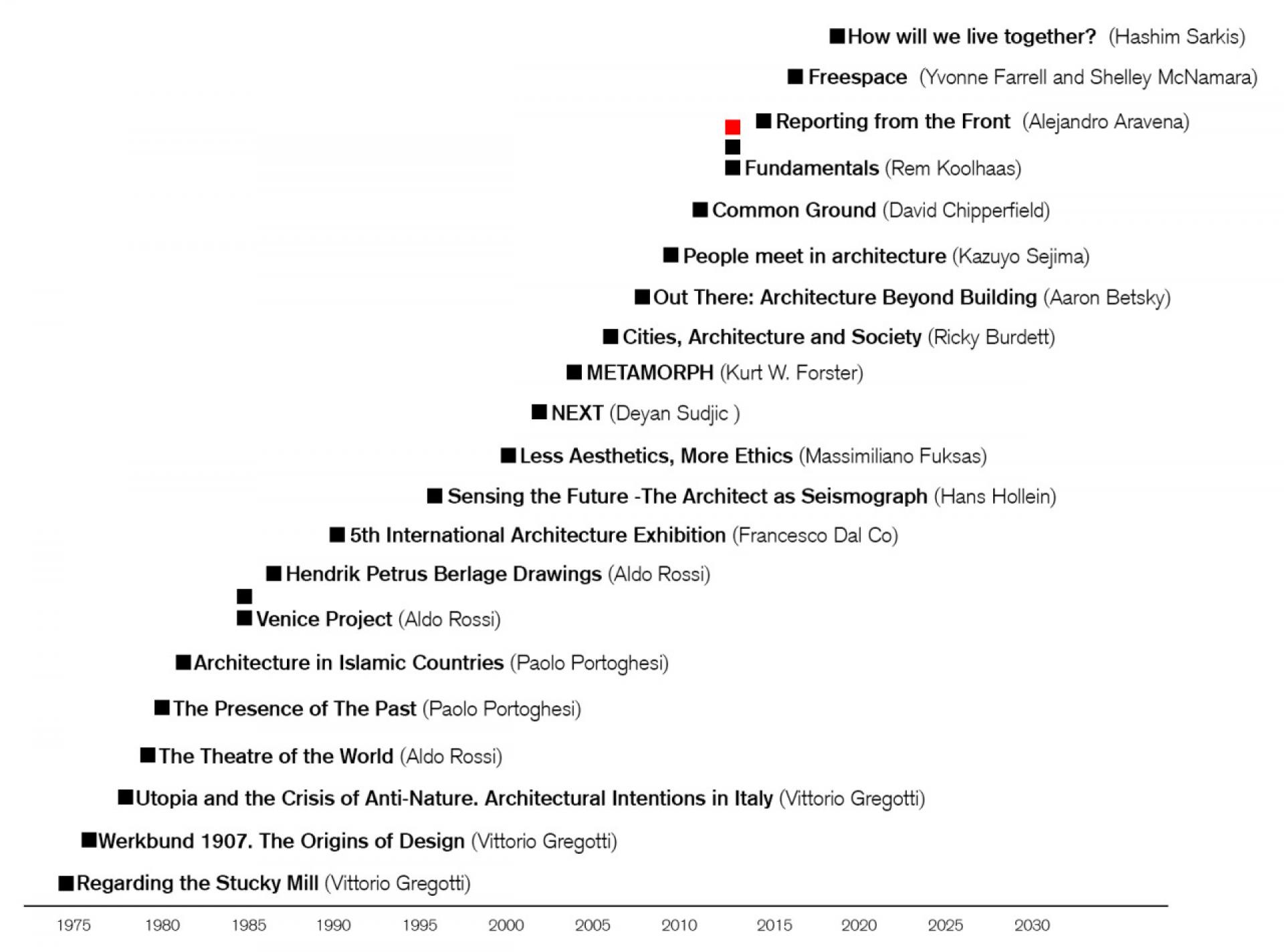

We all know that exhibiting architecture is a more than difficult task. If I exhibit art, I hang on walls, put in space or install outside the art objects “themselves”. The visitors will come to see the artworks in their reality, they will share their presence at the same time, in the same place. But if I exhibit architecture, I deal with plans, photographs, façades, sections, models. All those things are representations of architecture, not the thing itself. It’s probably why, in 2014, in a more than radical gesture, Rem Koolhaas decided to reduce architecture to its elements: floor, roof, stairs, window, etc. to be able to exhibit those parts in real, as in a large hardware store. No representations can replace the experience of visiting a building and not all the visitors of an architecture exhibition are able to spend time figuring space looking at two-dimensional drawings. Of course, the last years have seen an increase of 3D models, interactive videos, or Augmented Reality tools. (And even if low-cost flights have democratized trips, one should not overestimate our ability to travel, especially today.) We need architecture exhibitions to address questions and topics, not to experience a pseudo-psychedelic light-show à la Elíasson. Because nothing can replace the smell of freshly oiled wood in the Fisher House by Louis I. Kahn, the violent summer sun over the Barcelona Pavilion in a July afternoon or the welcoming old lady that generously opened her door and shared her life with me in her patio house from Arne Jacobsen in the Berlin-Hansaviertel.

We face a double problem: artists behave like architects by building installations and large-scale projects (without being able to address the real problems of architecture) or architects behave like artists by enjoying the freedom that their everyday business doesn’t allow (without being able to produce a real work of art). That’s probably why, as a matter of fact, a lot of pavilions in Venice turn towards interior design or utopia projects when it comes to exhibit architecture. And those who refuse those strategies simply translate the content of a book into space (with too much text and documentation, a mistake that “elements of architecture”did).

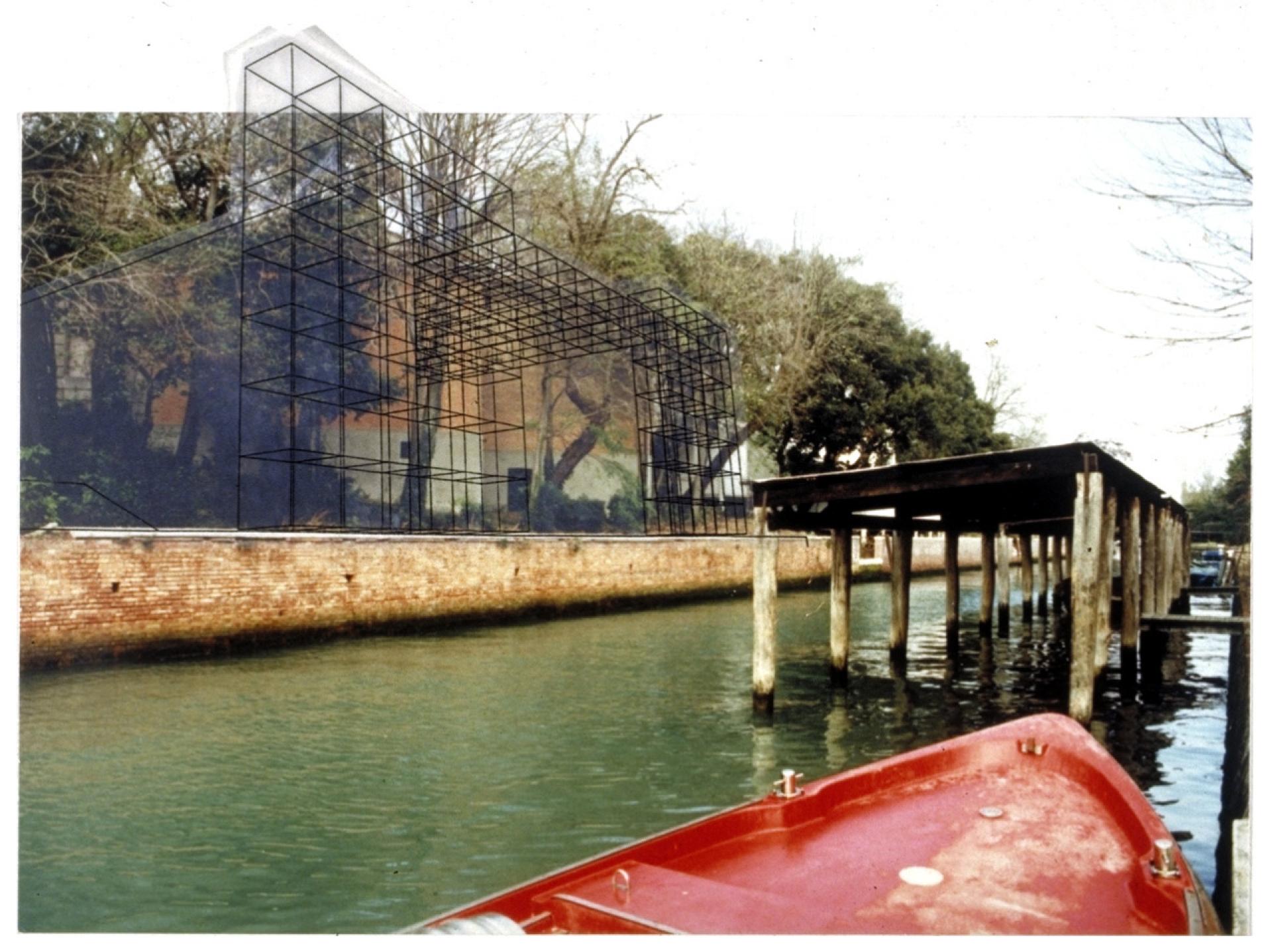

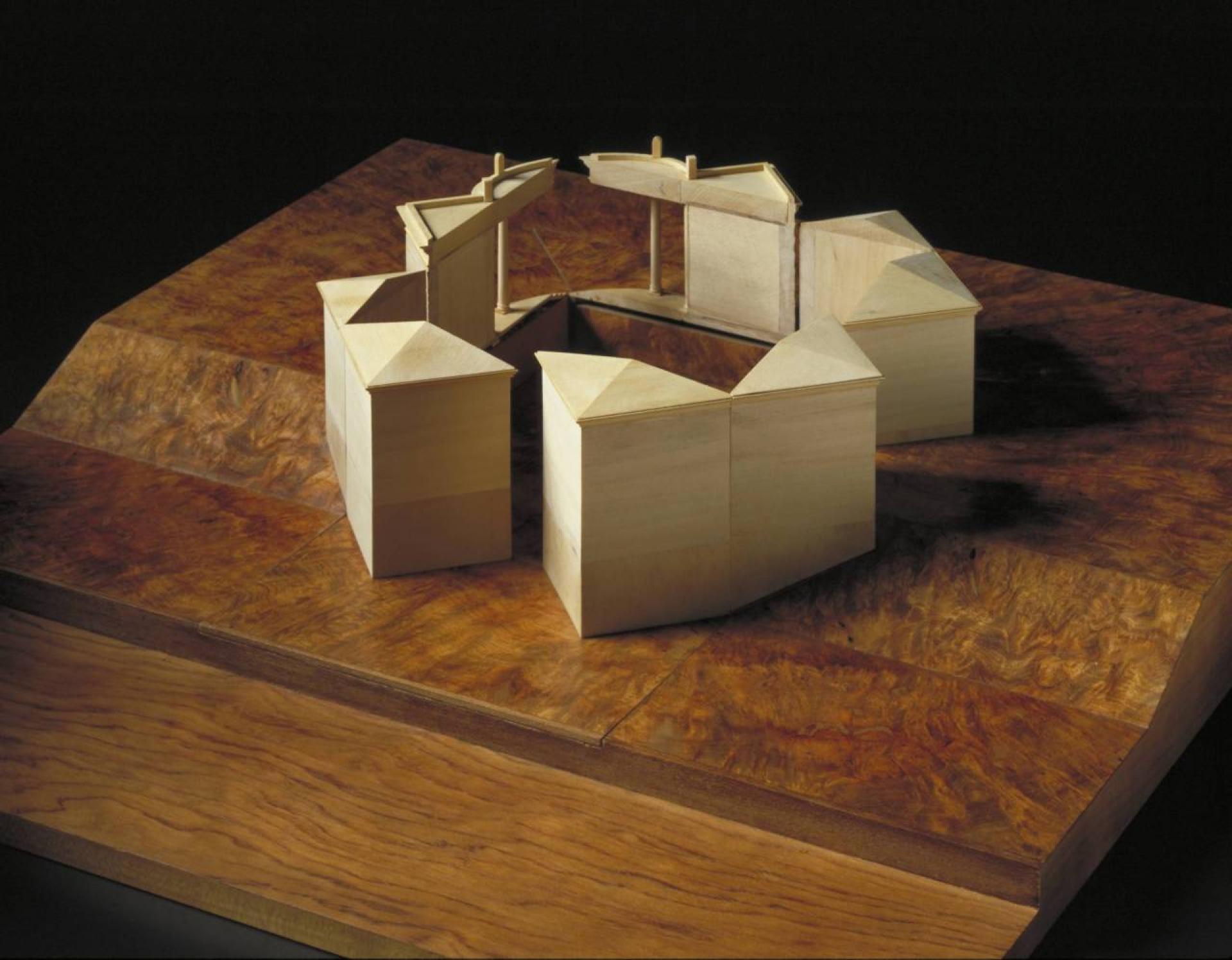

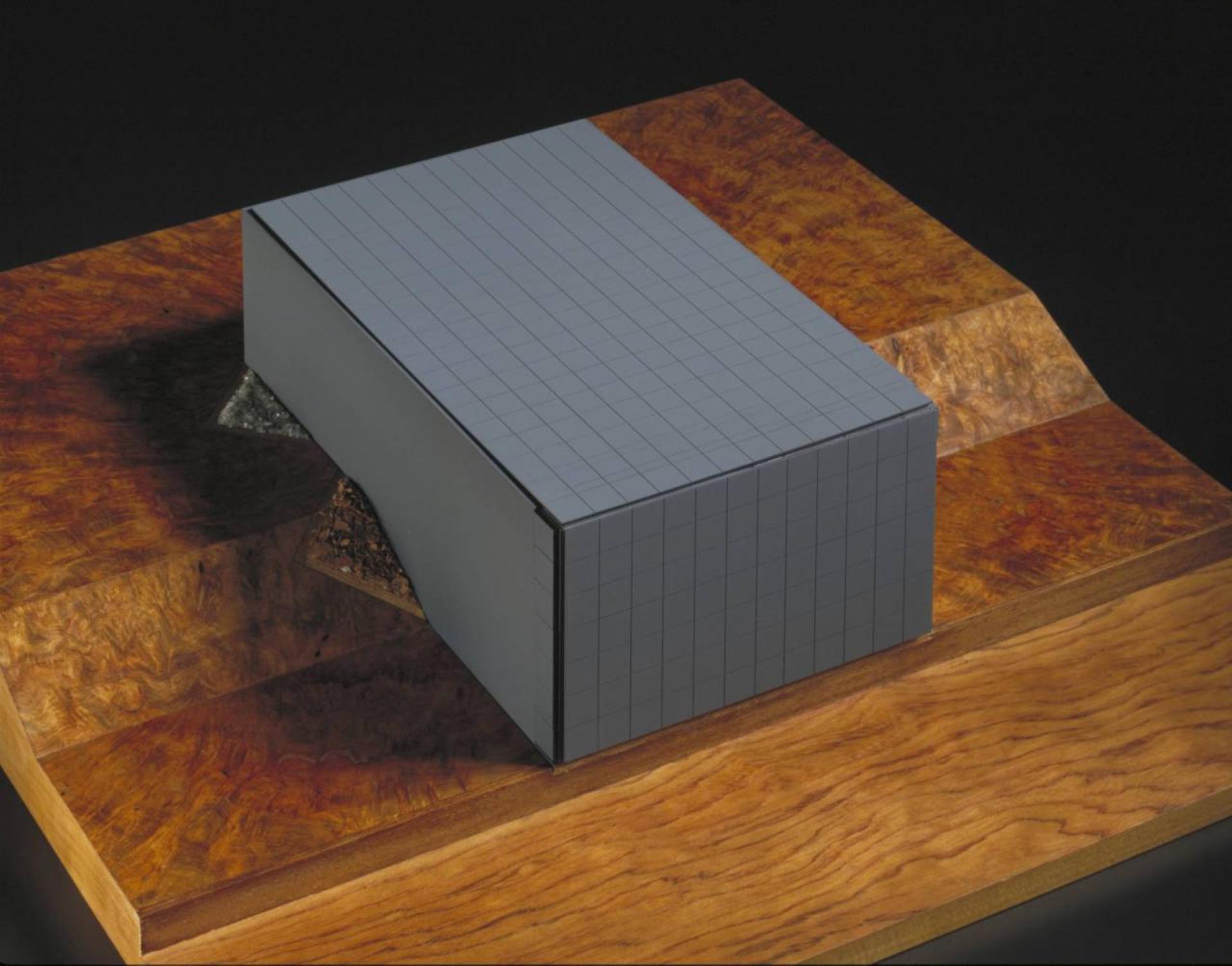

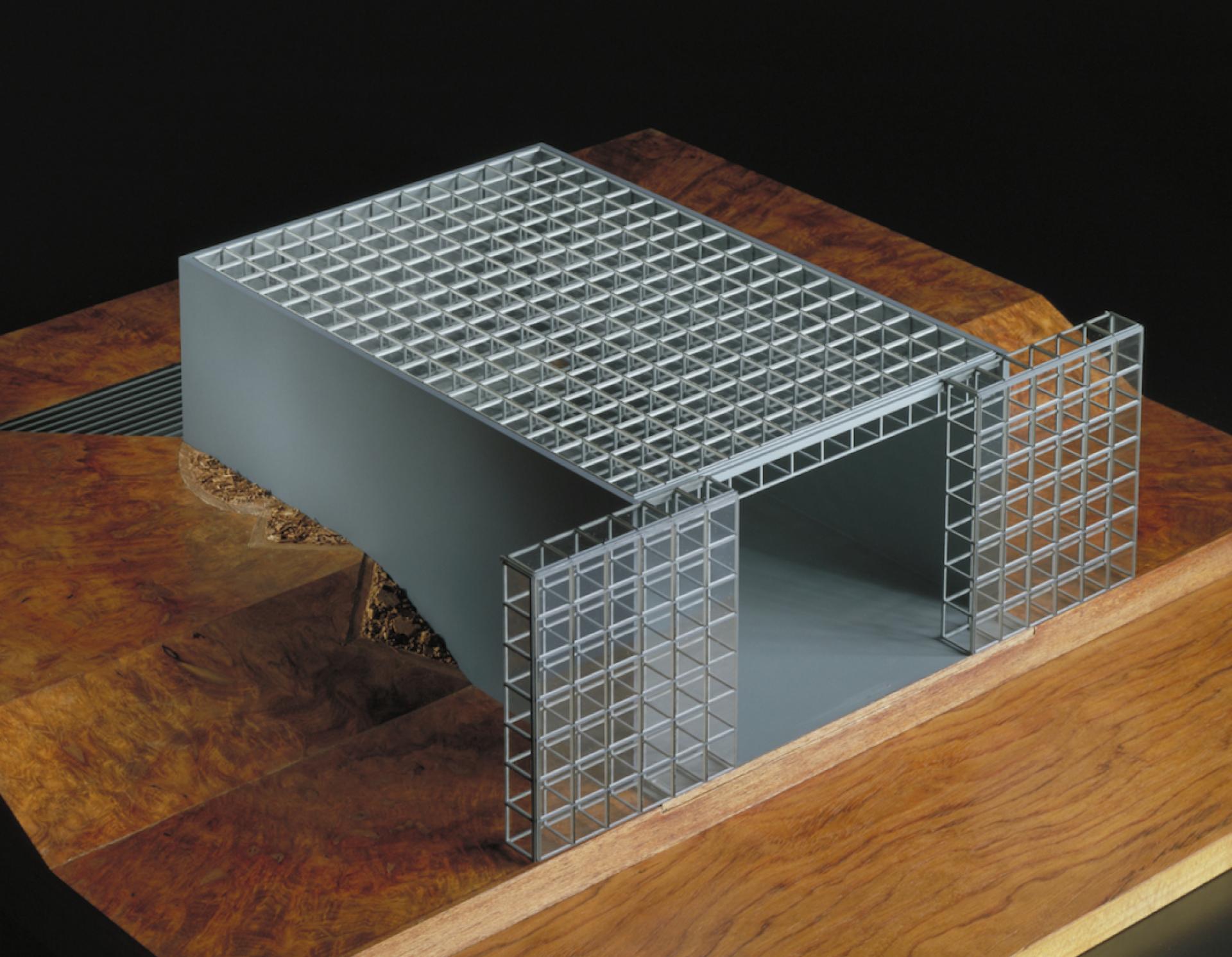

Proposal for the French Pavilion at the XLIV Venice Biennial of Art. | Project © Jean Nouvel, Emmanuel Cattani & Associes; photos © Georges Fessy

If, tomorrow, I was asked to curate a pavilion in the Venice Architecture Biennial, not as the last participant in the project but as the first one generating its concept, I will be confronted by a serious problem. I might then probably use the same strategy as Jean-Louis Froment who, in 1990, invited Jean Nouvel, Philippe Starck and Christian de Portzamparc to propose three projects towards the reconstruction of the French Pavilion. Nouvel conceived a whole scenario that will have lasted four years and, at the end, meant that the building from 1912 by Faust Finzi and Umberto Belloto would have been entirely replaced by his own. It was a brilliant proposal that dealt with architectural regulations (and another “cold case” as it was neverconstructed), and it would be a chance for the contemporary artists to exhibit in a space that fits their actual needs and requirements. If the whole process and concept proposed by Nouvel had something from Gordon Matta-Clark—and therefore of an architect behaving like an artist—the result would have also been a political statement and national symbol: France would own nowadays a brand-new pavilion with up-to-date technique and space, constructed by a contemporary architect. And the architect would have exhibited and done what he is supposed to do: a construction.

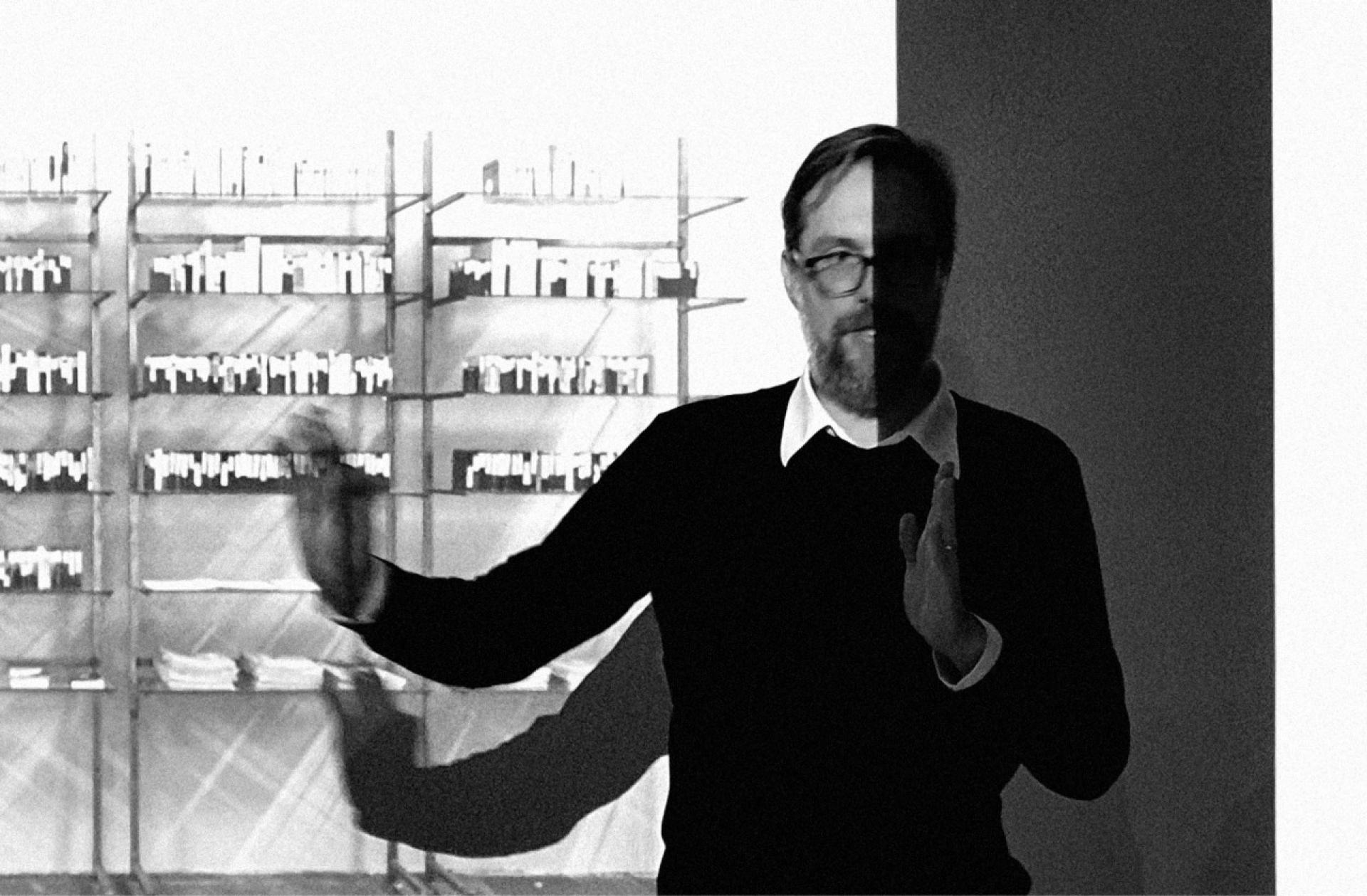

Thibaut de Ruyter is a french architect, curator and critic. He has been living and working in Berlin since 2001. His interests are based on new media and their archeology, the relationship between art and architecture, and the artistic scene in post-soviet countries and particularly in Central Asia. His latest projects are a travelling exhibition for Goethe-Institut in Eastern Europe and Central Asia, Die Grenze (with Inke Arns) who was displayed in 11 cities between 2017 and 2019 while his exhibition A Song for Europe was presented at the V&A, London 2017 and Schauspielhaus, Stuttgart 2018. In 2019, on the occasion of the 100 birthday of the Bauhaus in Germany, he co-curated with Marjolaine Levy the exhibition 26 x Bauhaus that was to be seen in Berlin, Bremen and Munich. He edited or co-edited the books: Zeitgeist (Archive books, Berlin), Industrial on tour and Industrial Research (Revolver Verlag, Berlin) and Stadtbild (Verbrecher Verlag, Berlin). As an art and architecture critic, he writes or has been writing for the magazines Artpress, Il Giornale dell’Architettura, Fucking Good Art, Frieze d/e, L'Architecture d’Aujourd’hui and Architectuul. In 2015 he co-founded ALUAN, the first Kazakh art magazine, with Gaisha Madanova. He has been a member of the French section of AICA (International Association of Art Critics) since 2008. | Photo © Bella Sabirova