The Great Island Of Replicas

“The Architecture of Pure Silence” - proposal for the 2016 Venice Biennale Contested Fronts by Constantinos Marcou

Since 1974, Nicosia still remains until today the only divided capital when the island was divided after decades of conflict into the two parts: the Greek Cypriot side and the Turkish Cypriot side. A green zone or a no man’s land, as it is often used to describe it, separates the borders of the Greek-Cypriot part and the Turkish-Cypriot. Exceptional in its own way, this strip is not only constituted by fences or military bases but it is an in-between territory controlled by the UN forces. It is there to act as a neutral territory for the two sides and politically exists as a spatiotemporal border in order to re-configurate future conditions of borders.

“The Great Island of Replicas”, Chapter 1: A topography of monuments

In the meantime, the act of separation and the spatial consequences of the political conflict gave birth, on an existential level the need to dwell, within a distorted understanding of what the two sides perceived as familiar. Domestic spaces were adapted. Streets were renamed. Monuments were either neglected or used as significant sites for the inscription of national ideologies, gradually producing culturally homogenous sides. Narratives were suppressed, often displaced, history became one dimensional and what remains, beyond the horrors of the past, are the artifacts that were salvaged by the refugees from their households during the conflict. The Buffer Zone on the other hand remained the only untouched territory were dusted forgotten objects, the absence of subjectivities, the abandoned and once habituated houses, the gardens and rivers no-one can cross, the leftovers of important historical moments, are camouflaged by a delirious and romanticized perception, often projected as an attraction or a territory for environmental study.

“The Great Island of Replicas”, Chapter 2: A colony of Lost Artifacts

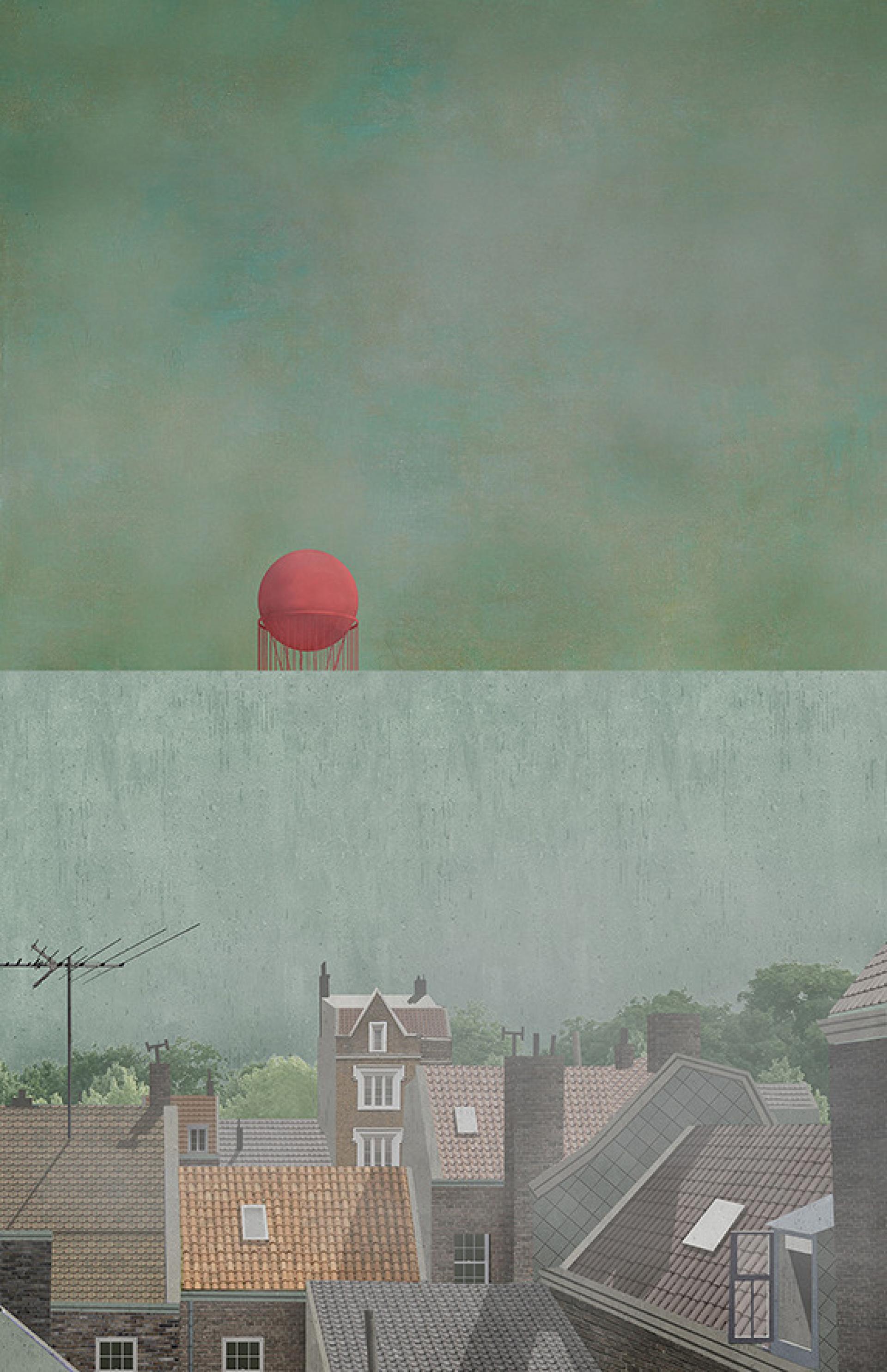

Loss and the horror for the unfamiliar can take various forms, often leading to unorthodox or extreme acts. “The Great Island of Replicas”, while an illustrated story, is an homage to such post-traumatic territories where everyday life and normality is disrupted by the unexpected creation of ruins within our cities. The story takes place in a post-apocalyptic era and it is in fact a dialogue between a journalist and an Archaeologist. The Archaeologist, the protagonist, is presented as a past member of a secret organization who was in charge of dealing with the trauma that occurred or still occurs to what the public understands as familiar, worthy of being part of history and important for the image of the city. Creating Archives, mapping, documenting, replacing the ruins with replicas are some of the acts that took place in the story.

“The Great Island of Replicas”, Chapter 3: Within the Wall

Without ever actual referring to the case of Cyprus, allegories were used both in text and in the representation, constructing the poetic for the narrative: a social argument that the idea of loss shapes not only the way individuals view space but the collective cultural production in different scales.

“The Great Island of Replicas”, Chapter 4: Familiar Ruins

“… The lady in blue opened the door inviting the young journalist inside her hotel room… As a historian she has grown accustomed to the great divide between the certainty for the familiar and what she knew to exist beyond this delirious obsession.

“I would like to thank you” he said while placing his recorder on the wooden table “for choosing my column to go public with your story” he added.

The lady in blue hesitated to answer immediately. Second thoughts were running through her mind but everything has led to this moment, she thought while starring outside the window.

“This is a story far from the imaginary. People have this tendency for getting lost in the stories they tell themselves late at night because they know that those kind of stories won’t disrupt their reality. This story is not my story. It belongs to the cities. It is our cities’ story”

“What should I call you?”

“Vienna” said the lady in blue…” [1]

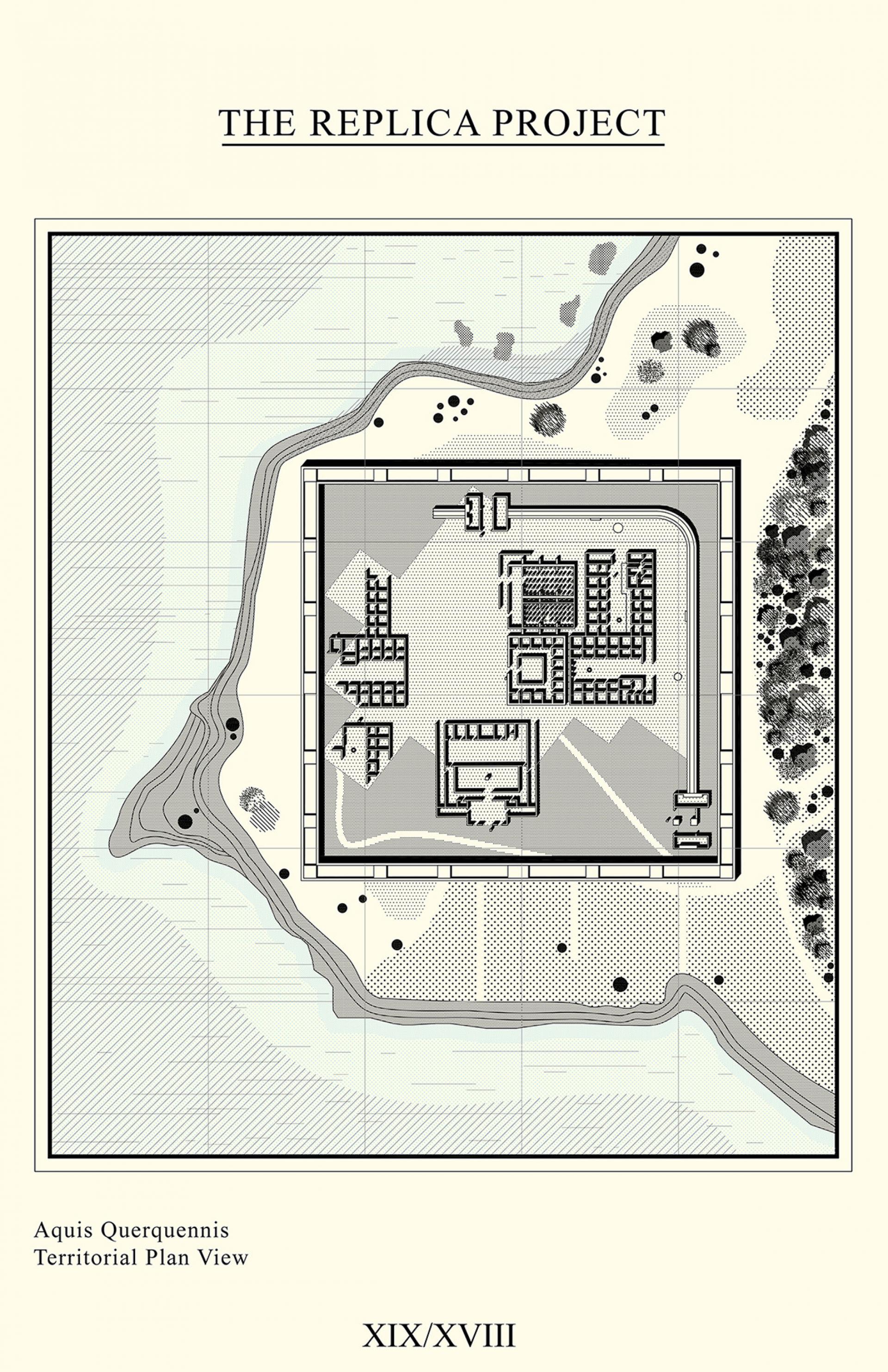

“The Great Island of Replicas”, Chapter 5: The Replica Project

When writing about Poetics Aristotle spoke about how Poetry as an art was based on imitating aspects of everyday life and human interaction, projecting at the same time the ethics, the society’s guiding principles. In the mid-90’s, the French Art critic Nicolas Bourriaud’s invented the term relational aesthetics, describing it as “a set of practices which take as their theoretical and practical point of departure the whole of human relations and their social context”.

If Architecture is not just built matter but the embodiment of values, idelologies and the affects of human interaction, then communication and representation, knowledge and information need to be understood as fundamental assets having a material reality. It is important to abandon the distinction between the real and the virtual and to understand how architecture is able to raise problems by using the different means of communication productively, as instruments, for problematization, questioning the category of the urban.

—

by Constantinos Marcou

[1] Constantinos Marcou, “The Great Island of Replicas”, Chapter 1: A topography of Monuments, 2019. The illustrated story won an honourable mention at the Blank Space’s annual Fairytale Competition in 2019.