Kyong Park: Future Communities

The Laboratory of the Future is the theme of next year’s 18th International Architecture exhibition in Venice led by Ghanaian-Scottish architect Lesley Lokko who became the first black curator to helm the event. The exhibition at Korean Pavilion "2086: Together How?” will explore global issues such as the pandemic, economic disparities, environmental disasters, social and political crises. Kyong Park, the co-director of the pavilion, takes South Korea as an example, whose hyper-centralized economy, culture and education generates regions formed increasingly by aging populations who live in landscapes where the empty and the abandoned prevail. It is within this context that he first developed CiViChon, City in a Village in 2021, an initiative on how to create an imaginary future at the scale of the village, rendering global, national, and local concerns to become more intimate, tangible, and relatable.

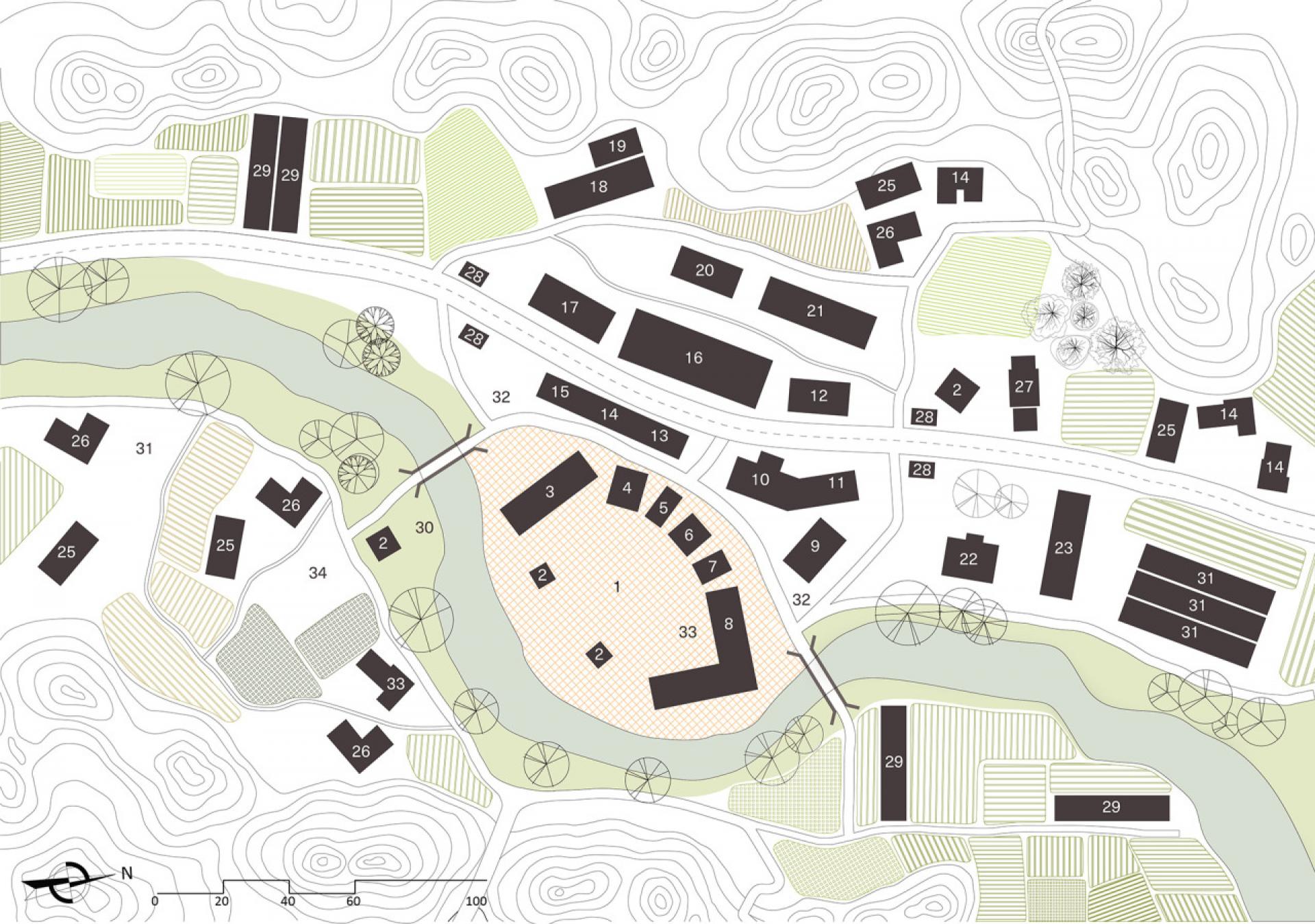

CiViChon Masterplan

In your concept for the Venice biennale presentation you are questioning why are we isolated when we are supposed to be connected through the globalization of information, finance, commodities, and even in culture?

Kyong Park: The project asks how we might live together in the year when our global population is supposed to peak. It posits that we need to realize a biocultural revolution if we are going to endure the unimaginable levels of environmental crises to come, which have already begun. Starting with three communities in South Korea, 2086 imagines a more empathetic, reflective, and restrained life in a new ecosphere. The project begins with the research and design collaboration of three teams, each composed of architects and community leaders, at three different regeneration projects currently active in South Korea. Located in a global city, a small city, and a village, together they serve to investigate the process of urbanization, modernization, and Westernization of Korean urban and rural history. Employing real activities at real locations, the project will then take them toward 2086 by engaging in set dialectics that have been determinant factors in our biocultural evolution.

Very complex!

KP: Yes, well the project hypothesizes that environmental crises will radically alter our community, society, and could even bring a new paradigm to human civilization. We also think that our environmental crises are not just the rise of the sea level, the planetary temperature, CO2 emissions or other material and atmospheric pollutants. The problems are actually within us, within our body and mind, and how we have embarked on a Faustian-like ideology of progress for unlimited material pleasures through industrialization, urbanization, modernization, colonization and globalization, in which architecture and urbanism are their instrument, expression and record. Thus, 2086 thinks that the environmental crises can best be resolved through a reformation of our way of living and thinking, and through a reassessment of our history and legacy.

What is CiViChon, a model of a city in a village?

KP: CiViChon (Ci - City, Vi - Village, Chon - a Korean euphemistic word for villages and rural areas) is an idea to observe the division between the city, urban and rural areas. Mainly because of the urbanisations that have happened around the world in the last one and half century which have radically changed the way of living, the architecture and the society. It was an instrumental part of western domination that has spread around the world, radically transforming the ways of our life. Its latest version is globalization, the neo-liberal policy of colonizing the rest of the world without necessarily invading it. In the concept of CiViChon urban and rural is reconsidered, as urbanization approaches its maximum level in the developed economy and market territories where ruralization is beginning to take place.

An installation view of CiViChon: City in a Village, in Vienna Biennale 2021: Climate Care, MAK (Museum of Applied Arts) Vienna, Austria. Photo © Georg Mayer/MAK. 2021

What happened in Korea?

KP: As a result of urbanization and development, almost 82 % of South Koreans now live in urban areas while almost 52% in high rise apartments, and 50.4% of its 52 millions lives in Seoul metropolitan area. It is highly urbanized and centralized. Many accused such a high level of centralization to be part of the legacy of the military dictatorship period, where the developmental policy was extremely geared towards its panopticon-like national territorialization. Since then there’s been many efforts to decentralize its population and economy. There also has been decentralization of political power by giving greater budget and political autonomy to the local governments.

So we talk only about the development of the metropolitan areas again?

KP: No, there also has been an attempt to revitalize the heavily depopulated and aging population in villages with government policy and financial support for business entrepreneurships and cultural activities trying to get younger people to move into small villages and towns. But what I hear from the experts is that the programs have not been so successful.

Nomadic Forums for Future Communities: “Place Centered Community or People Centered Community?” Gunsan City, South Korea by CiViChon 2.0. | Photo © Yuran Kim, 2022

Why not?

KP: Many say that they are mired by lack of creativity and sustainability. Others say that the private sector has been more successful because they are driven by more urgency by self investments. But this could be the same old argument that capitalism is more efficient than the public sector, when dealing with any developments. The private sector has been more successful because they are driven by more urgency by self investments and have been more creative and much more sustainable.

Is behind all this any budget?

KP: I don’t know the exact amount but many say that there has been a significant financial effort made by the national and state government and even cities and towns in rural areas have provided significant support to potential residents and entrepreneurs.

What about localization, is it becoming a new trend?

KP: The ideal of localism is gaining popularity in South Korea. It can be considered even as a multigenerational movement. There are retired people who are moving aways from the city because they are no longer economically tied to the city through their jobs. Some of them are returning to the villages of their origin. Then there is a middle age group who tries to find alternative life form away from working for companies, and romanticizing to live self-sufficient and independent. The younger generations are moving into the rural area as well, because they find living in the city too expensive and not enough economic opportunities. Those who move to the rural area are called Kwichon, and those who try to farm are called Kwinong.

Nomadic Forums for Future Communities: “Place Centered Community or People Centered Community?” Gunsan City, South Korea by CiViChon 2.0. | Photo © Yuran Kim, 2022

How are the younger generations living in a village?

KP: They are considering whether they would be able to build their new future in the rural environment. In a lot of villages there are hipster bars, coffee shops, boutiques, and some of them are trying to find local commodities and traditional products, try to modernize and brand them and plug them into the contemporary market. They are bringing a new economy to the rural areas by capturing the tourists from the city and providing services that are familiar to urban people. The younger generation is in such a way transporting their urban life form in the village environment.

How about Europe?

KP: A week ago I met a member of the Robida collective in a village called Topolo, where a group of young people are building a community in a small village in the mountains on the Italian side near the border with Slovenia. There is a strong experiment and effort of localism for building an interdependence relationship in a small community by making a common kitchen, library and other common space where people can get together to become a collective group.

Is behind moving out from the cities also a lack of sense of belonging?

KP: There are many factors behind the early ruralization, moving from the cities to the countryside. One is the capitalist dilemma as the nation becomes wealthier and produces disparity and inequality of wealth. Many people in the city feel that they can not compete and survive in the city anymore. People feel an attraction to the communitarian way of life that is missing in the cities. The rural environment provides them a romantic view and people are searching for an idealized rural life that would enable them a better intimate, social and physical life in a smaller place. Then there is also the getting away from the capitalist system and network that people can live in cheaper space, cultivating food and be in such a way self-sufficient. They also seek to lower the level of dependence on money and get a slower life to do something that they can enjoy in it. People want to be liberated from capitalism. There are many complex desires and directions that can come together in the idea of localism, like independence, self-sufficiency, liberation from the big economic regime.

Nomadic Forums for Future Communities: “Place Centered Community or People Centered Community?” Gunsan City, South Korea by CiViChon 2.0. | Photo © Kyong Park, 2022

During the pandemia you mentioned that we are all in this not together?

KP: When the COVID-19 happened the campaign slogan in the USA was We are all in it together. This was an ideal to generate collective behavior in order to fight the virus together. The cultural notion in the USA is based on individualism which undermines this collective effort. People refused to wear masks and take vaccines in great percentages and there were people who claimed that this is a violation of their individual right and freedom. I felt very frustrated comparing the situation in the USA and South Korea where people were behaving collectively, working as a group. This is the big difference where the people in the USA are wearing masks thinking they will protect them from other people infecting them. In South Korea people are wearing masks for the opposite reason, because they do it in order to not infect other people.

Kyong Park | Photo © Jipil Jung, 2022

Kyong Park is a professor in the Department of Visual Arts at the University of California, San Diego (since 2007) and was the founding director of StoreFront for Art and Architecture in New York (1982–1998); the International Center for Urban Ecology in Detroit (1998–2001); and the Centrala Foundation for Future Cities in Rotterdam (2005–2006). There, he co-produced "Lost Highway Expedition," an expedition through nine major cities of ex-Yugoslavia and Albania in 25 days, in which several hundred people participated [2006]. He was a curator for the Gwangju Biennale (1997) and the Artistic Director and Chief Curator for the Anyang Public Art Project 2010 in Korea, where he curated 30 projects and commissioned 23 international artists, including Suzanne Lacy, Marjetica Potrč, Rick Lowe, Raumlabor, Lot-ek, Mass Studies, Chan-Kyong Park. Kyong Park was also a Loeb Fellow at Harvard University (1996/97), Visiting Chair of Urbanism at the University of Detroit Mercy, School of Architecture (2000-2001), and the editor of “Urban Ecology: Detroit and Beyond,” a book on his projects, with contributions from 32 architects, artists and critics [2005]. His solo exhibitions are Kyong Park: New Silk Road at the Museo de Arte Contemporàneo de Castilla y León in Spain (2009–10), and Imagining New Eurasia, a sequence of three research art exhibitions that visualized continental and urban relations between East and West, which was commissioned and exhibited at the Asia Culture Center in Gwangju, South Korea (2015–18). He is the author of Urban Ecology: Detroit and Beyond (2005) and Imagining Eurasia: Visualizing A Continental History (2019).