Why To Destroy Cities And Capitalism!

Let’s Build Pyramids: Why to Destroy Cities and Capitalism!

For a series of different reasons, Andrej Tarkovski’s Nostalghia seems very actual as it portrays the image of the cities during these days of lockdown. In the most emblematic scene of the film, Domenico, the old madmen who enclosed his family at home for seven years attending the end of the world, gives a public speech from the top of the Equestrian Statues of Marco Aurelio in the Campidoglio square in Rome. Listening to him are a very few groups of mad, foolish and ordinary people standing on the different monumental stairs of Michelangelo’s piazza. In the scene, actors are symmetrically positioned on a precise and identical large-distance from one another echoing, in some rhetorical but also poetical terms, a sort of future scenario on how we’ll have to imagine one of the most crowded spaces in Rome and elsewhere if social distancing becomes a new way of living.

Apart from the poetics of social distancing and its anticipation, what emerges from Tarkovski’s film is also a different perception of space and time opposed to our everyday-life habits: namely when Gorchakov, the protagonist, steps in his large hotel room, where it is shown only the bed and the sink, when he meets Eugenia in the hotel hall and when he visits the thermal bath of Bagno Vignoni. In two hours of film, all these few passages and dialogs are shown very slowly, slow shootings with only a few actors, offering a sort of dilated space, which again recalls how cities and metropolis have been spatially transformed from when silence and emptiness reigns supreme since Covid-19 spread globally. In these days, which seems that will last for a long time, seen from the point of view of domestic segregation (mediatically called quarantine), comes clear on how much we are used to and educated to live in cities and how we suffer it now. We all work in offices, study in schools and universities, consume in supermarkets and shops and do travel for all these reasons abroad, away from home, which we use only as a sleeping-place when we turn back from outside by car, tram or bus.

Assuming all these activities and rituals as fundamental aspects for reproducing life, while thinking also to the urban form of contemporary towns, historical centers, metropolis and megalopolis, it clearly emerges that the very reason behind these common rituals are mobility and circulation. As we all can observe, without working infrastructures, without metros, tram-lines, car roads and highways, cities would have no sense. I thus argue that this is related to a contemporary crisis of space, which is a very tangible condition in actual problematics such as climate change, pandemic crisis, scarcity of land in cities as also in the countryside, as well as the property issue and housing shortage, the problem of minimum dwellings and high rents, conditions that are strongly related to the existence of the city and its urban form.

Wuhan: No One Cares

Who did theorize well the dialectic between circulation and the crisis of space was Karl Marx. In his Grundrisse Notebooks, Marx argues that within the circulation process, which is part of the whole process of production, Capital through the concept of time destroys the concept of space itself: “Capital by its nature drives beyond every spatial barrier. Thus, the creation of the physical conditions of exchange – of the means of communication and transport – the annihilation of space by time– becomes an extraordinary necessity for it.” [1] The circulation process, namely the process of exchange of goods, labor force, money and capitals, is the process where products are transformed into goods and this takes place within the so-called global market.

As Marx put it out, in order to surpass any barrier, the production of cheap means of communication and transportation is fundamental to capital, that is why their realization is promoted by capital itself: “The sea route, as the route which moves and is transformed under its own impetus, is that of trading peoples ϰατ᾽ ἐξοχήν [pur excellence]. On the other side, highways originally fall to the community, later for a long period to the governments, as pure deductions from production, deducted from the common surplus product of the country, but do not constitute a source of its wealth, i.e. do not cover their production costs.” [2] To say it in more simplistic words, it is capital alone or through the intervention of the State that needs to build streets and communication routes connecting cities (market centers) through the territory, and doing so as quick as possible.

As we think to the form of the city since its origins, as highlighted by Henry Heller in his book The Birth of Capitalism: A 21st Century Perspective, the urban fabric of the medieval town was a fundamental apparatus in accelerating the passage from feudalism to capitalism. Collecting different arguments of historians and researchers on feudalism, Heller tries to explain the role of the formation of towns in a passage that coincided with the rise of the town both as a marketplace and as a terrain of class struggles.

University of North Carolina Campus (1860). | Source: Turner, Campus: An American Planning Tradition

From the contemporary point of view of its most sophisticated form that is financial capitalism, David Harvey have always asserted that this aspect of accumulation and exchange is embodied in the ideology of the political agendas of growth. As highlighted by Harvey in one his lecture at Harvard Senior Loeb Scholar, after the 2008 crisis, while the UE promoted austerity policies, on the contrary, countries like Brazil or China pointed towards extreme growth (and urbanization) implementing large investments in order to increase employments and escape from economic depression. Examples like the Chinese project launched in 2013 to merge together Beijing, Tianjin and Hebei into a megalopolis of 130 million people called Jing-Jin-Ji, demonstrates not a mere imperialistic geo-strategic plan, but it also reconfigures the logic of financial capital applied to an archetype which does exists as capitalism does too: the city. In such a context, criticizing the city means contemporarily criticizing capitalism and its logics of production and reproduction. For this reason, through the history of architecture and urbanism the unbearable aura of capitalism and its logics has produced many alternatives by proposing models that served as attempts to escape from, to govern and to destroy it.

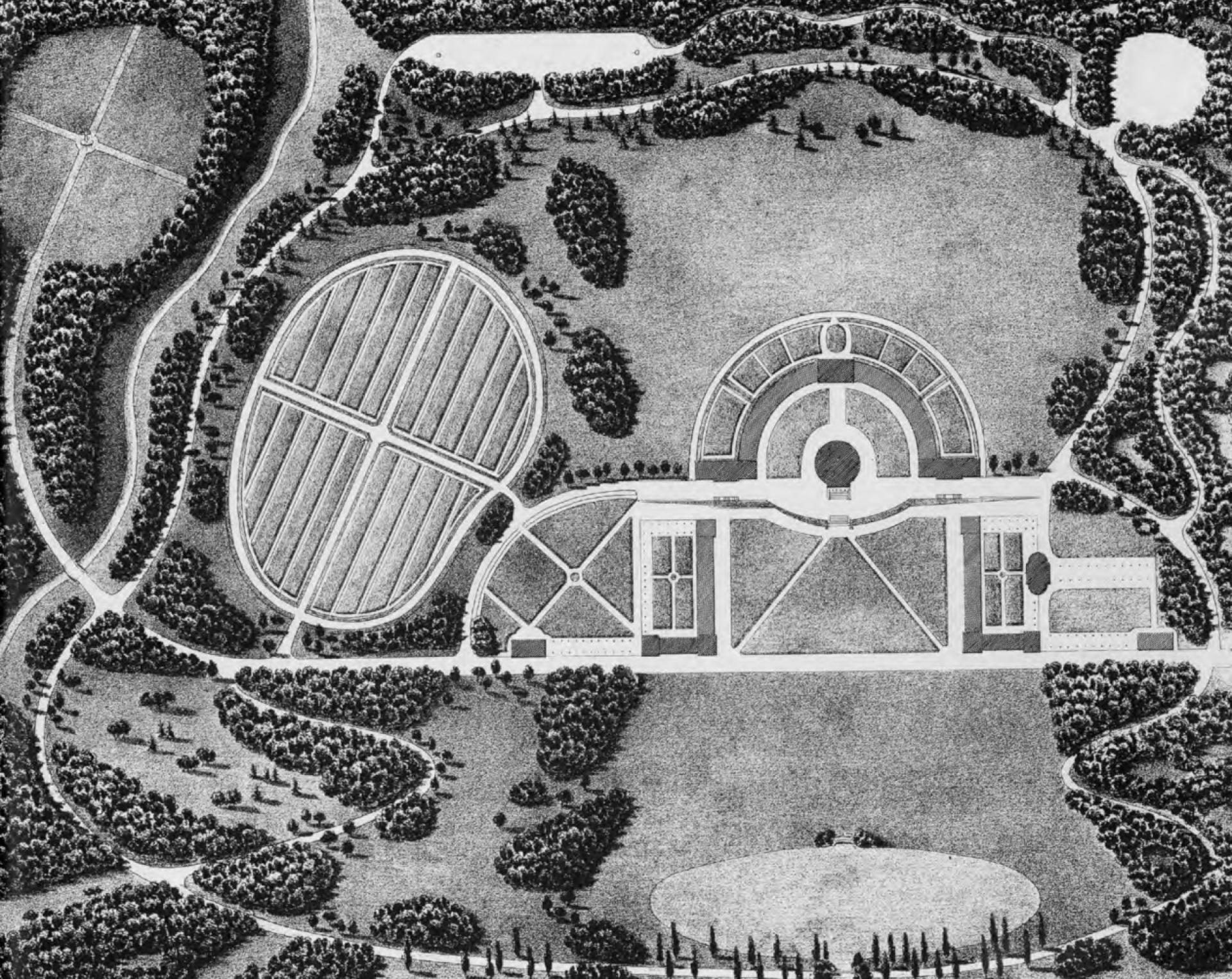

Union College, Schenectady (NY), Project and drawings by Joseph-Jacques Ramée (1813). | Source: Turner, Campus: An American Planning Tradition

Escape was one of the main reasons behind the invention and ethos of campus planning in the USA in late 1700s. When university and education in the United States became a political project, for many campus planners the only way to make education efficacious was to build them far away from the city, in order to avoid its corruption, distractions, profligacy and chaos. The word campus, coming from Latin campo that literally means an open field, according to Paul Venable Turner was first used at Princeton College in the 1770s referring to the property land of its first college building [3].

From then, putting a group of buildings within the idyllic nature enhanced an alternative to organize life differently. Eliphalet Not, president of Union College during 1804-66, became popular through college pioneers for having invented a way of living and a new governance based on family life principles. During Nott’s governance, each professor was responsible of his class and had to consider it as his enlarged own family. This model of less-control over students structured a new democratic life that corresponded also to the architectural form of the college designed by French architect and landscaper Joseph-Jacques Ramée: a rotunda at the center of the campus and symmetrical wings of dormitories and classes limiting a natural common space where students and professors could live and work together as members of a large family.

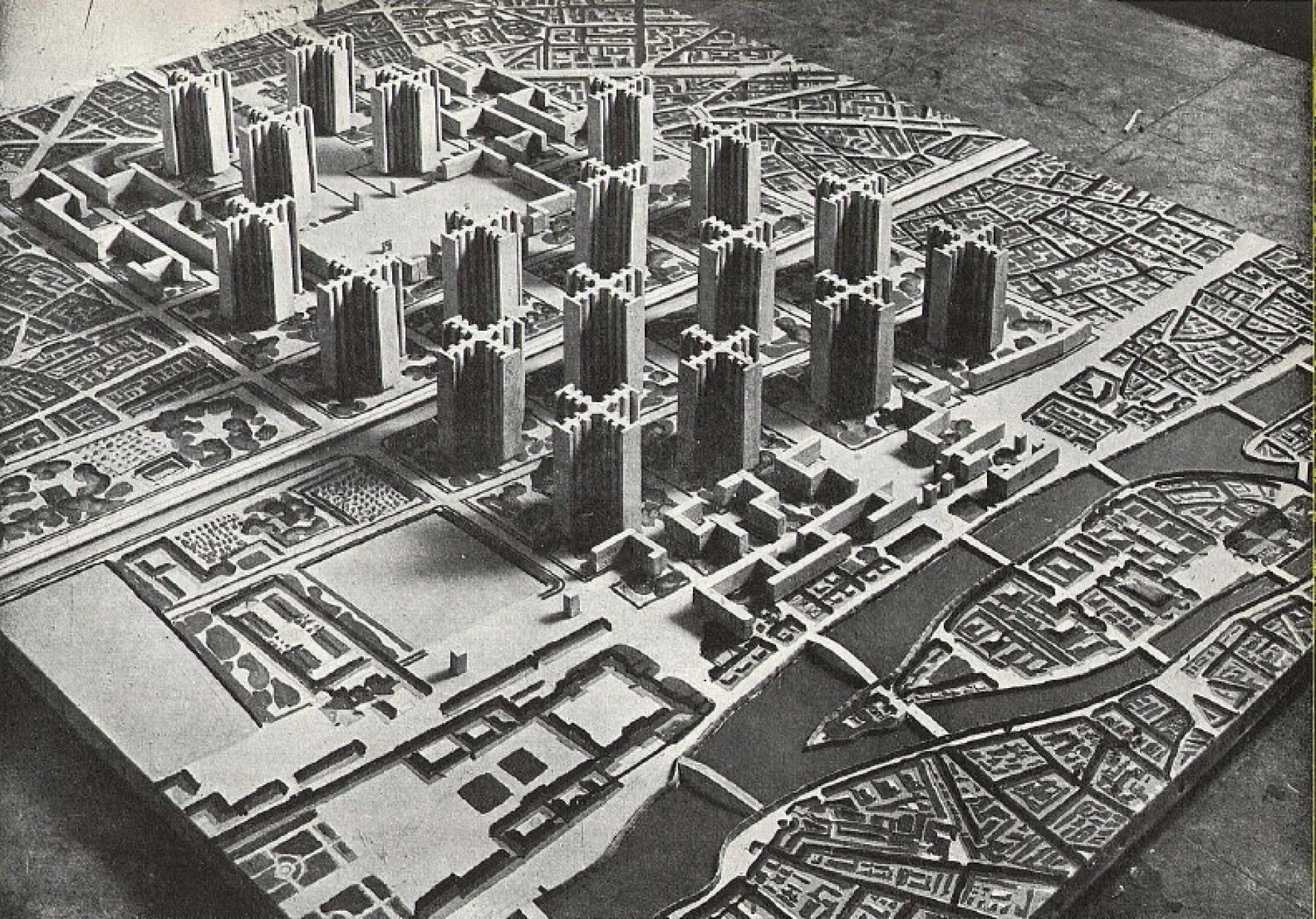

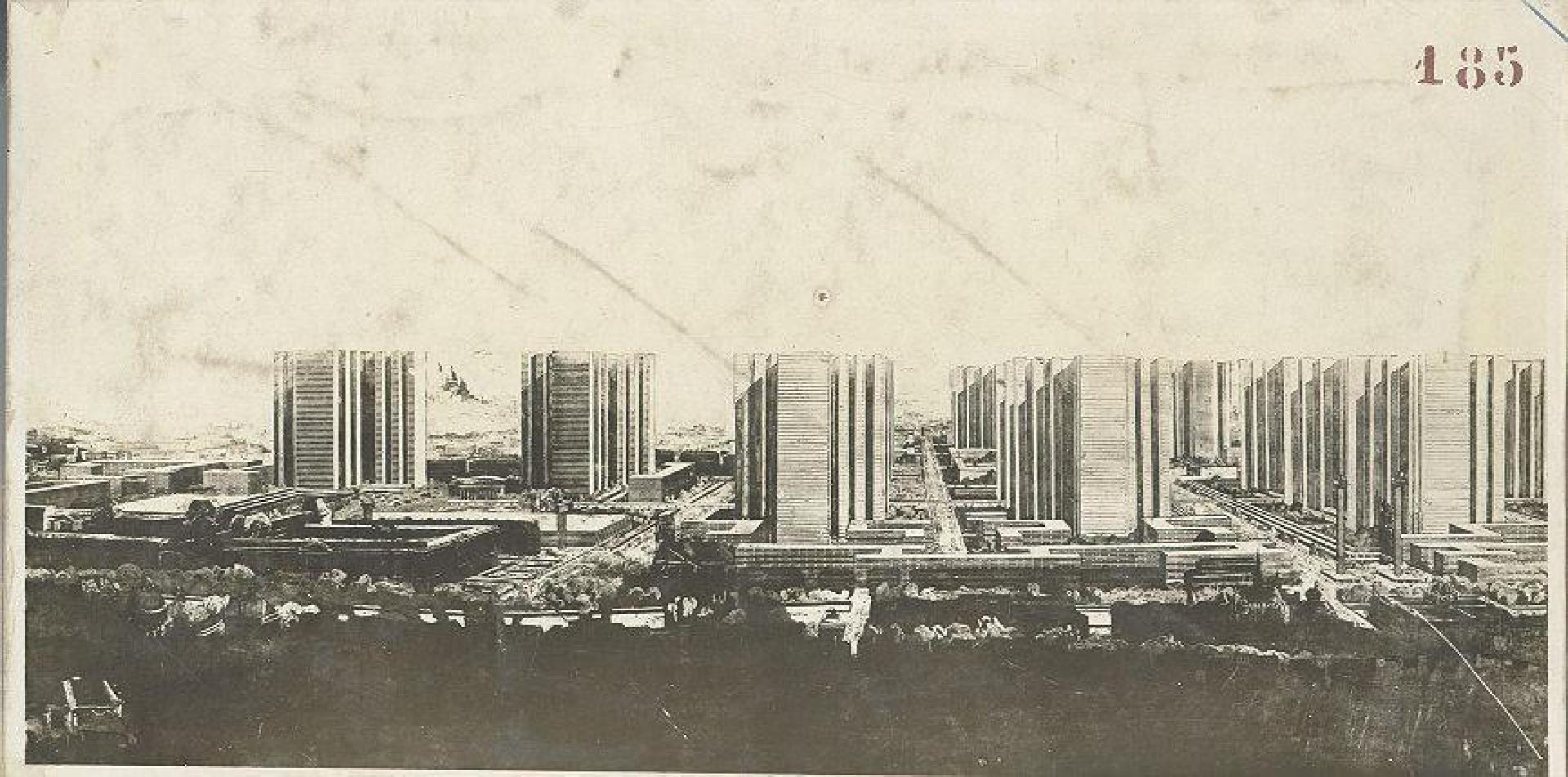

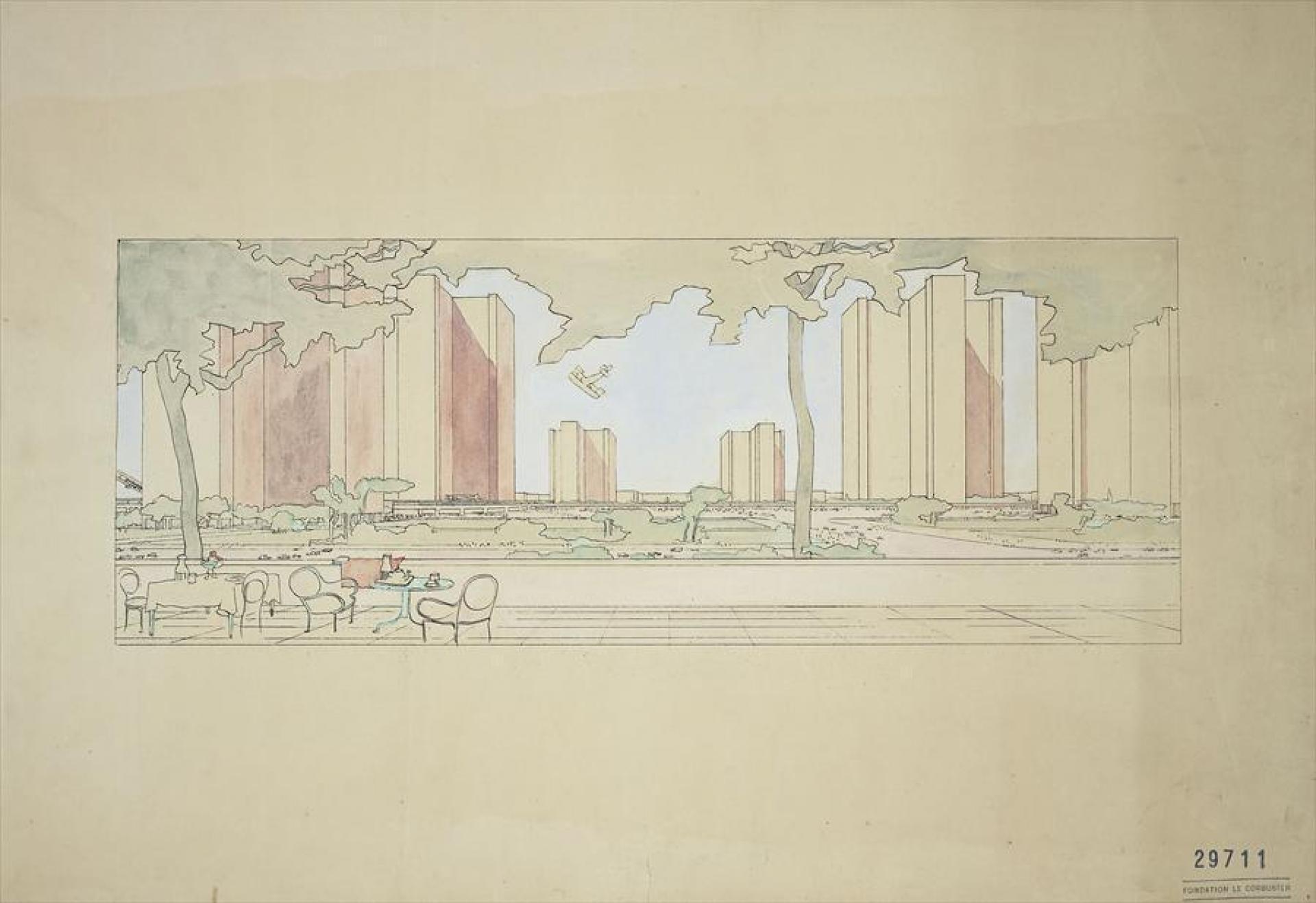

Ville Contemporaine. | Source Der Stadtstreicher

Revisiting the same architectural and organizational model, the spread over the American territory of almost identical models such as Thomas Jefferson’s Virginia University, first projects for the Davidson College in North Carolina, plans for a National University near Washington and the Stanford University, echoed in certain ways Robert Owen’s parallelograms for a socialist utopia where mutual-cooperation based on living, working and centralized education could be organized within self-sufficient bodies spread over a farming landscape [8]. Everything but socialism, American university campuses however represented a dilated spatiality inhabited by students moving around in groups, social distanced or close to each other, and with buildings placed here-and-there into an open field full of trees, lakes, forests and idyllic green.

Fascinated by this same depiction of university campuses, yet operating through the same ideals of nature, but more perverse and decisive, Le Corbusier’s plans of Ville Contemporaine for three million inhabitants of 1922 and Plan Voisin of 1925, strongly opposing urbanism as we are all used to know it, can be considered as one of the most radical attempts to destroy the city and its historical aura.

Plan Voisin. | Source Charnel House

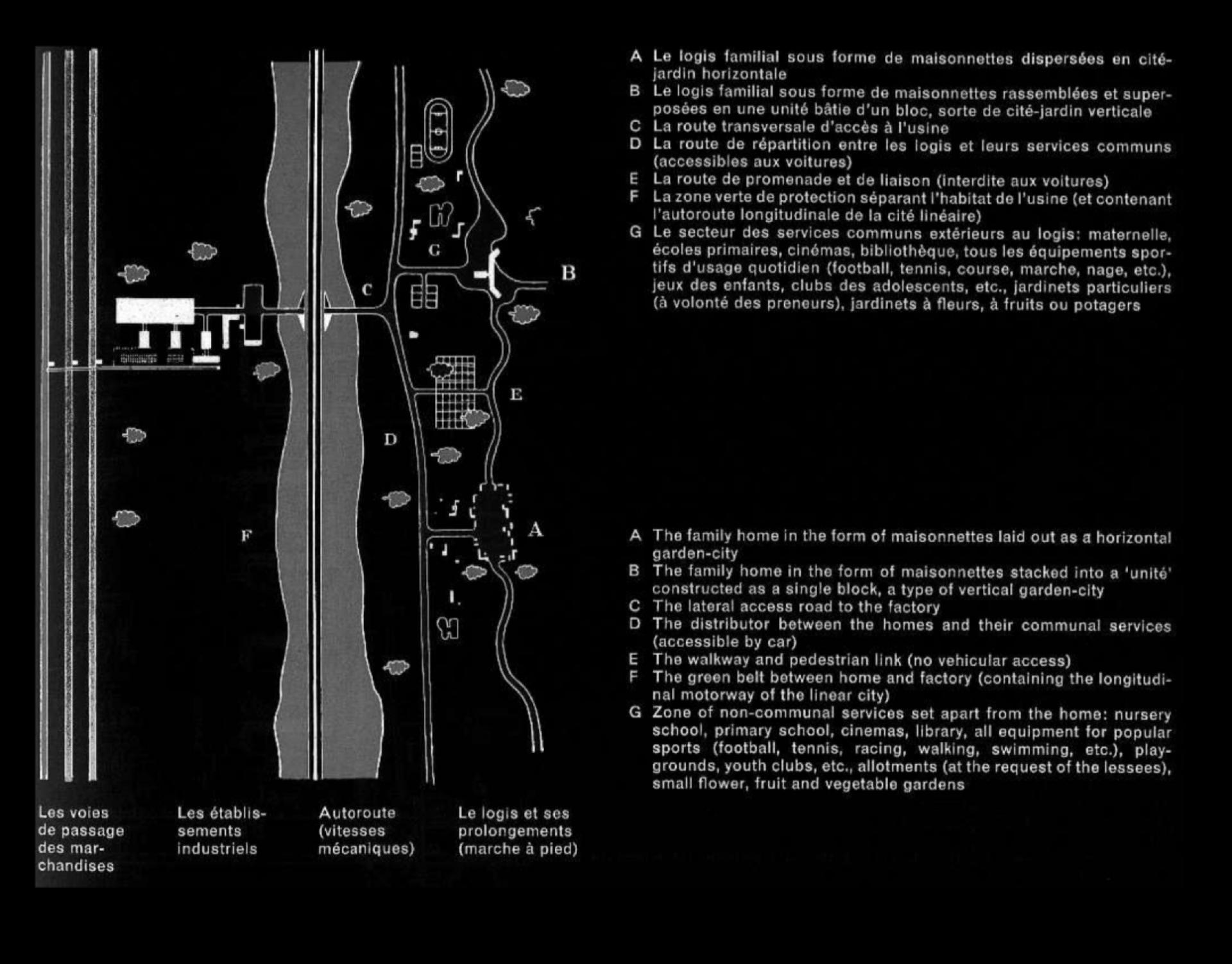

While in both the two proposals the Swiss architect insisted on demolishing an entire piece of historical Paris for erecting his prototypical settlement with towers and low-rise buildings into an enormous park, the very response to the logic of capitalism was his Industrial Linear City elaborated together with the CIAM-France group of the ASCORAL in 1942-43 [5]. In the latter, Le Corbusier imagined a series of territorial strips (with highways and railways) connecting European most important historical centers through horizontal and vertical territorial axis containing housing, productive buildings and free-standing agricultural settlements.

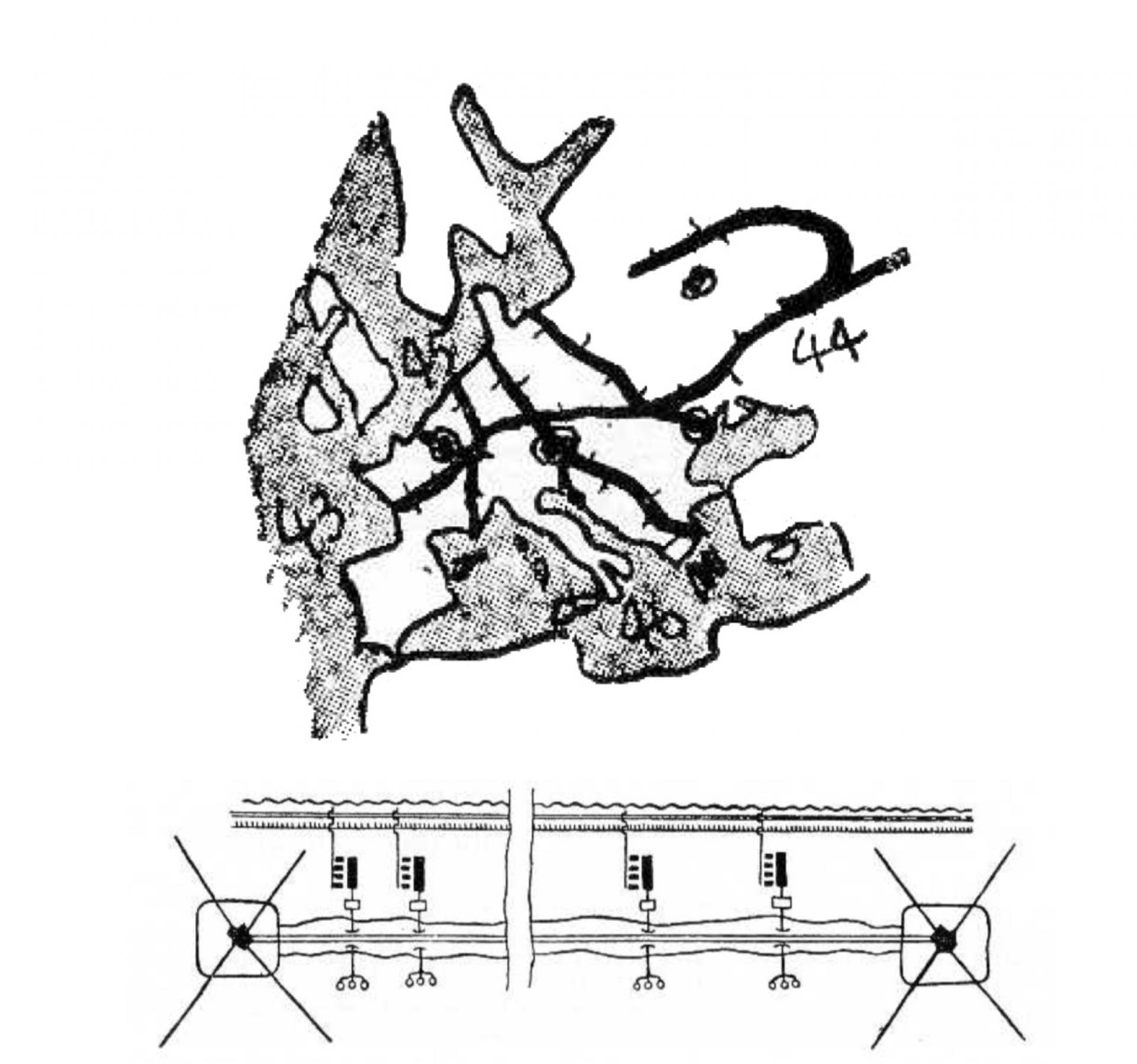

Diagram of the Industrial Linear City through Europe and fragment of the linear city connecting two historical centers (1942-43), Le Corbusier + ASCORAL. | Source Le Corbusier - Œuvre complète Volume 4: 1938-1946

In his vision he literally stretched the typical industrial city assuming the highway, that became a greenway, as its structural form: thus, historical centers in Le Corbusier’s vision were reduced into ordinary administrative bodies and exchange hubs—likely in the same way we intend Amazon distribution centers operating today—connected to each other by highways bordered with a green belt and rhythmed through factories and isolated Unité d’Habitations, horizontal garden-cities and facilities. The linear form assumed the infrastructure by explicating it in a new architecture dispositive for a new dilated city, the habitability of which could be imagined by thinking to the point of view of an adventure foreigner-guy traveling and sleeping in highway motels when stopping in filling stations.Though, rather than a real alternative to the capitalistic city, Le Corbusier’s linear city can be considered as a design diagram to control and govern accumulation and to give a specific form to the logic of growth against that neoliberalist laissez faire model that came after Le Corbusier era.

Detail of the Industrial Linear City (1942-43), Le Corbusier + ASCORAL. | Source: Le Corbusier - Œuvre complète Volume 4: 1938-1946

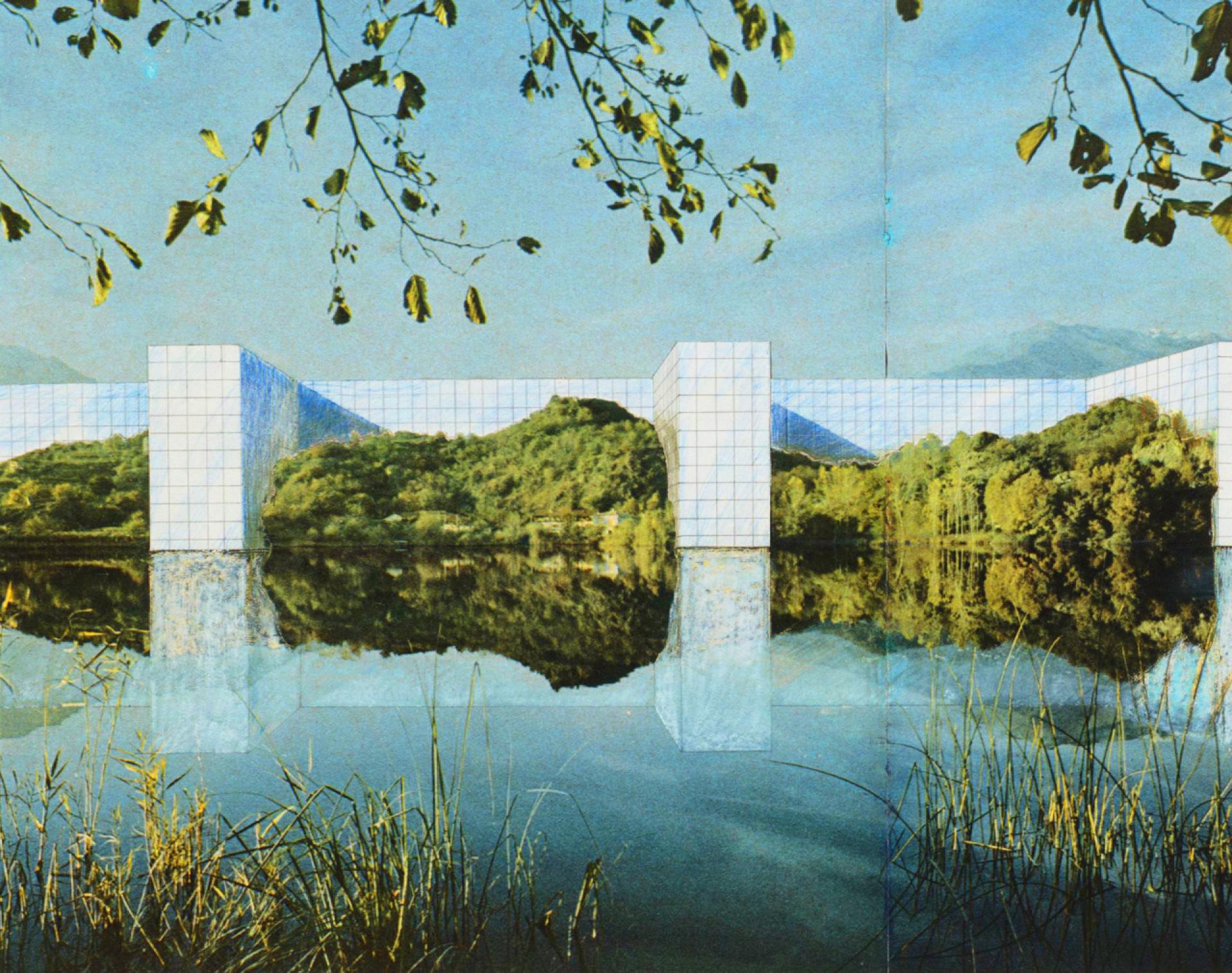

What Le Corbusier presented as a mere opposition, the disurbanization of the world imagined by the Italian collective Superstudio with their Continuous Monument, an enormous infinite white-grid element cannibalizing the city, to quote a very potent expression used by the Italian architectural historian Roberto Gargiani, collects all the frustration of an entire young generation emerging from the political struggles between 1968 and 1977 against industrial capitalism in Europe. While in the first collages of 1969-70 this imposing element cannibalizes the city in the sense that it really penetrates it by destroying emblematic landscapes such as Graz, Madrid, Rome, Florence and New York, in the latest collages of 1970-72 this immense monument could finally run through in full liberty: into world’s nature, canyons, deserts, valleys and rivers [6].

As Gargiani and Beatrice Lampariello have carefully narrated in their book Il Monumento Continuo di Superstudio, tracing its origins, infrastructure highways and viaducts were crucial references on the Superstudio research discourse by images as these infrastructures really addressed them on how to use one of the most emblematic inventions of capitalism for circulation in favor to a new spatial alternative. Inside the Continuous Monument, echoing Joseph Paxton’s Crystal Palace interior,—there have to be no rooms, no labor-division, no hierarchies, no typology and no program—just a free and pure envelope of nothingness. Rituals and forms of life had to take form in the same way urban communes and hippies did and, perhaps, life inside has to be governed in the same way the Italian autonomists were politically organized: through their same historical effort that helped to understand and made visible the inhabitability of the city.

Fragment of the Continuous Monument entitled Manhattan Empire State Building, Superstudio (1969-70)

It was nevertheless auspicabile that such critics emerged in times of gran abundance, on the apogee—to put it with Adam Smith terms—of the wealth of the nations. Although during modern and post-modern history of architecture there were many other examples going on the same direction, even more radical and polemic (i.e. soviet disurbanism linear aggregation of individual cells with episodic collective buildings is the most emblematic example towards the destruction of the capitalist city) [7], the three strategies analyzed above should tackle not a new projective aura, but, on the opposite, a ferocious critic to what have been done till now. The point is not to advance specific solutions but to raise questions and to address a hysterical reaction to everyday obviousness: Why are we at this point? Why streets and squares are there and we cannot reach them? Why did we all build them if, in a snap of fingers, they become inhabitable? Perhaps, because they have always been inhabitable—inhuman.

Fragment of the Continuous Monument On the River, Superstudio (1969-70)

Going back to Tarkovski’s message, the invitation to build Pyramids should be read not as a mere nostalghia of how we were living before the global lockdown. It should rather serve to think on an historical moment that is yet to come and could give the possibility to share that common anger that lays in our souls and spirits; to finally express it in the form of a common effort for destroying the command of capitalism and building marvelous pyramids for a new form of democracy.

Marson Korbi

—

[1], [2] Marx, K. (1073). Grundrisse. Foundations of the Critique of Political Economy, London: Penguin, 442, 449.

[3] Venable Turner, P. (1984). Campus: An American Planning Tradition Cambridge, MIT Press, 47.

[4] Benevolo, L. (2005). Le origini dell’urbanistica moderna, Laterza.

[5] Le Corbusier, eds. Willy Boesiger, Oeuvre Complète (1991). Zurich: Les Editions D'Architecture, 72-75.

[6] Gargiani, R., Lampariello,B. (2019). Il Monumento Continuo di Superstudio. Eccesso del razionalismo e strategia del rifiuto, Genova: Sagep Editori.

[7] Aureli, P. A., Martino, T. (2018). The Forest and the Cell: Notes on Mosej Ginzburg’s Green City. Harvard Design Magazine, no. 45.