Building Again

Armina Pilav presents Ivan Štraus notable with his architecture realizations of Imperial Board of Telecommunications in Addis Ababa (1969), UNIS Towers (1986), BH Electric Power Building (1978), Holiday Inn Hotel (1983) in Sarajevo and Museum of Aviation (1989) in Belgrade. Some of his works, like Olympic Press Centre in Bjelasnica (1983) were destroyed during the war in Bosnia and Herzegovina (1992-1996).

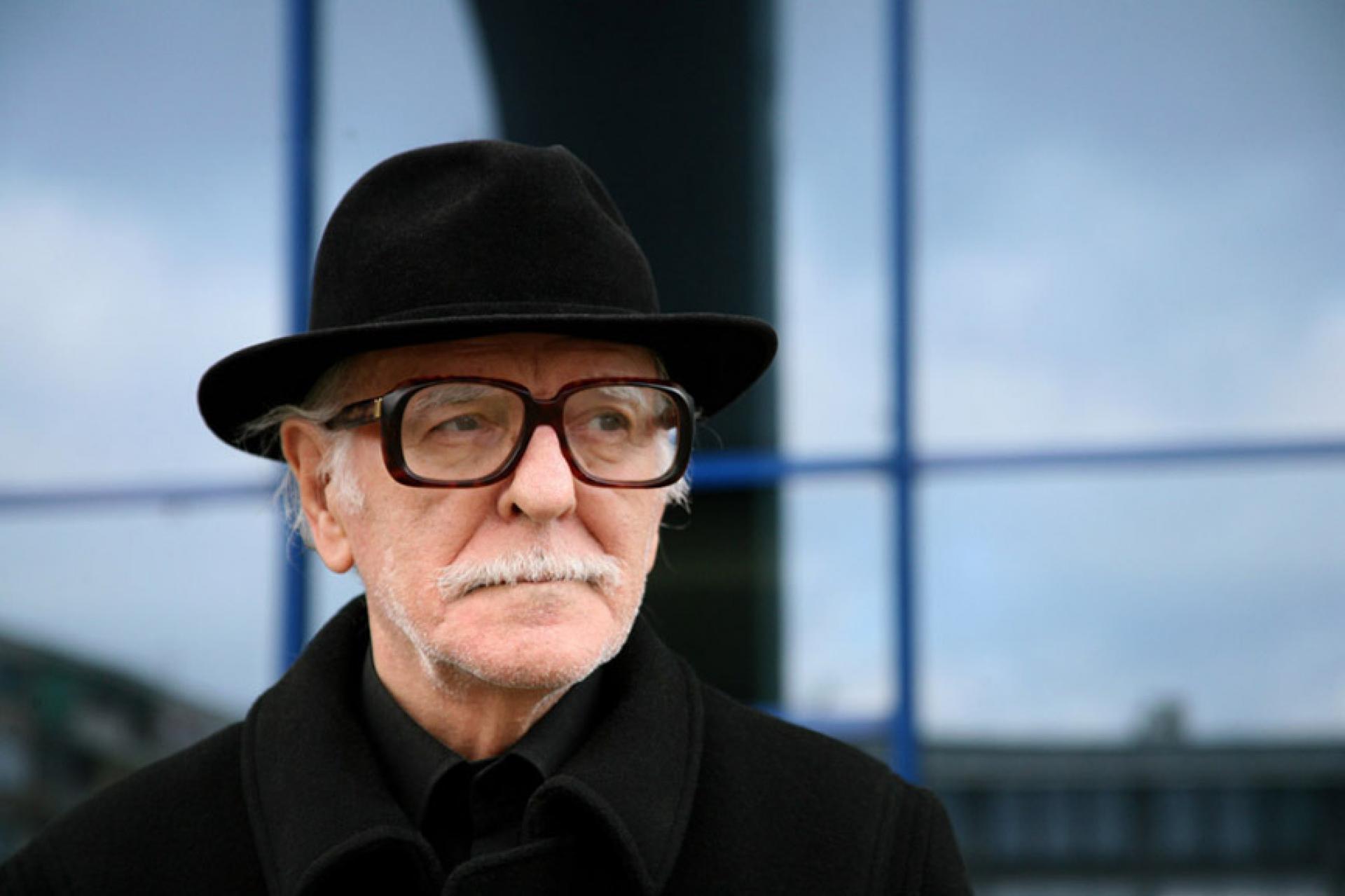

Ivan Štraus | Photo by Zoran Kanlić (2014)

Following several long conversations with Ivan Štraus, I came to realize that he represents a prism through which we can re-examine the task of architecture and the role of the architect during and after the war in Bosnia and Herzegovina and all Post-Yugoslav territory. His long and varied life experience allows us to consider the role of different generations of architects in the making of a complex architectural context. Sarajevo is an example of shifting political and material realities in which architecture continually acquires new meanings. It is a city where Štraus lives and still practices architecture through writing and conversations with journalist and architects.

This story is guided by Štraus’ thought that “architecture makes sense only as the practice of the present”. A very important figure in this story is Lebbeus Woods, who visited Sarajevo in 1993. He was taking the role of journalist, because during the siege, coming into and going out of the city was controlled and limited, and media workers were in the group of those who could access the city. Lebbeus brought with him a copy of a freshly printed pamphlet War and Architecture, which marked the beginning of an unusual relationship. Ivan Štraus spoke at the book presentation, appropriately staged in the destroyed building of the Olympic Museum. Following the visit, Štraus and Woods remained in contact, leading to some interesting exchanges about reconstruction. I found Ivan Štraus’ Architect and Barbarians [1], a diary he wrote during the first years of the siege of Sarajevo. Štraus’ witnessing was soon joined by the work of Lebbeus Woods, who saw the condition with an equally lucid eye, and gave it both verbal and visual articulation. This led to my interest in Štraus today: a rare architect who gained the opportunity to build again one of his destroyed buildings.

Destruction of Sarajevo. | Photo by Zoran Kanlić (1993-1994)

Wars on the territory of the Socialist Federative Republic of Yugoslavia, including the most brutal one, in Bosnia and Herzegovina, destroyed more than just significant architectural achievements. They also erased the names of architects who shaped socialist landscape in the period of 1945-1991. With the end of the war in Bosnia and Herzegovina in 1996, much of past modernist achievements became insignificant.

Ivan Štraus, once Yugoslav, today Bosnian architect of Slovenian origins responded to my phone call with a quiet and tired voice. Already in his late eighties, he nevertheless accepted the proposal to meet. He said he would do it for the sake of architecture and future generations. The first meeting with Štraus started with my prepared interview. I was asking question after question in a structured and formal way, and soon that turned out to be unnecessary, because his life and work cannot fit within the form of an interview. At the end of our meeting Štraus started to ask me questions. He also asked me if I could bring some examples of my architecture for the next meeting.

Ivan Štraus: Were you surprised by the decision of the Serbian Academy of Sciences and Art?

Armina Pilav: I was more surprised by you than by the Academy decision. I think by the way you accepted the invitation to join the Serbian Academy of Science, the idea in general.

Ivan Štraus: And what is that way you are talking about?

Armina Pilav: You said yes! It says enough about your culture of openness, the way of thinking.

Ivan Štraus: And about my consistency. Whenever it is about architecture, it is in first place.

Armina Pilav: It says a lot about the continuity of your thoughts, work, and the very act of accepting: “Yes, I accept your invitation to be a member of the Serbian Academy of Sciences and Art”, is a great thing. I think that no one would do it given to the political situation in our region, how people think and what is important about our cities. The way you did it, is a timeless act and something that cannot be located in any of our political or ideological contexts. You were thinking about your legacy that we will have one day.

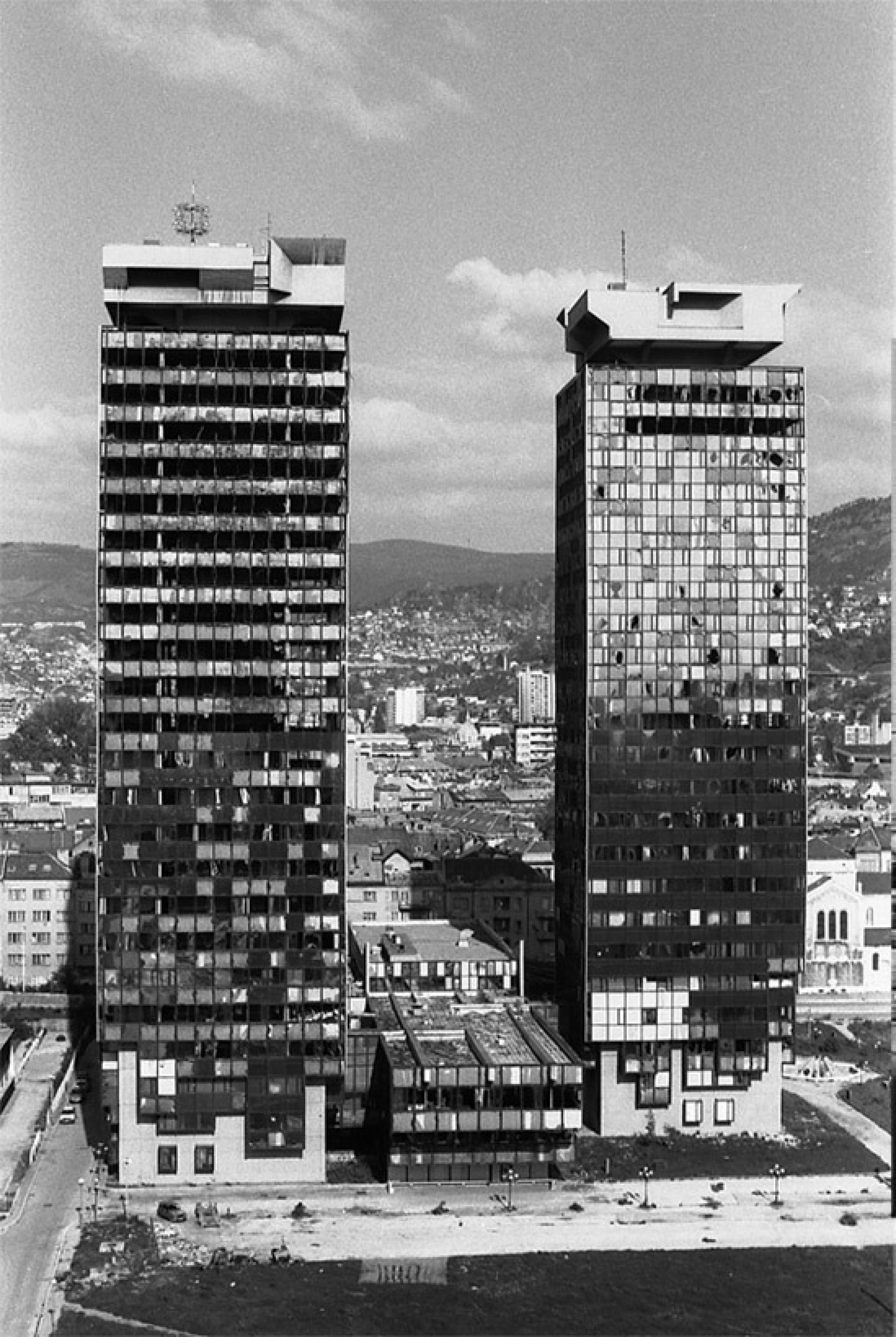

UNIS towers (1986) were renamed Momo and Uzeir, a symbol of Yugoslav brotherhood and unity in Sarajevo. | Photo © Zoran Kanlić (2015)

In the context of generational crossings of Bosnian architects, Štraus still has autonomy as architect, as he could choose to be both a member of Serbian Academy and a Bosnian architect who still remembers and was writing about Serbian forces that were destroying his buildings and the city. In Belgrade, at the ceremony for new members of the Serbian Academy, he signed one diary to one of his colleagues who lives in Belgrade. I understand Štraus’ consent to become a member of the Serbian Academy as an act of deterritorialization and reconceptualization of the conflict between Serbia and Bosnia and Herzegovina. And, finally including Croatia that will in the future turn out to be more successful than any other political-economical agreement between our countries.

Hotel Holliday Inn (1983) was a war residence for foreign reporters. | Photo by Zoran Kanlić (2015)

Building Again

As a consequence of the war in Bosnia and Herzegovina and the systematic destruction of cities (1992-1996), two buildings in Sarajevo designed by Štraus were rebuilt. The first is the Elektroprivreda office building on which he worked again after the war with almost the same prewar members of his design and construction team.

Elektroprivreda building in 1978. | Photo via Elektroprivreda archive

He decided to reconstruct Elektroprivreda up to the second floor keeping its pre-war concrete construction while, from the second floor to the top, war ruins were destroyed and removed, and that part of the building has been rebuilt.

Elektroprivreda served as the headquarters of the company for the power distribution of Bosnia and Herzegovina. | Photo © Zoran Kanlić

The second building is the Momo and Uzeir Towers. In this reconstruction he did not participate or, as he says, he was for political reasons excluded from the project. Apart from the war diary that I consider as important as all of his built houses, an additional reason to talk with Štraus has been to understand how the Sarajevo of today has been influenced by the processes of postwar reconstruction, and what it means to him to build again.

In spatial terms the war has changed the city and the city has changed us. Due to the systematic destruction of buildings and life in Sarajevo, new architectural and urban elements were created: the barricades, temporary, movable and immovable protection walls from sniper bullets for pedestrians, urban gardens on balconies for vegetables, trenches, temporary cemeteries in parks and sports fields, art galleries in ruined buildings, innovative man-powered transportation systems for wood, open buildings and houses without parts of their roofs, walls, windows, at that time creating for us “an unknown city – an open city, the truth of the city…view on the structure of life, buildings, neighbors‘ relation.”[2]

Destroyed school in the Ali Pašino neighborhood. | Photo © Armina Pilav (2014)

Although, at a quick glance, Sarajevo today looks, and is publicly presented as a renewed city, some of these war architectural and urban elements are still present in the central and the peripheral parts of the city, such as: half-destroyed buildings of the former Maršal Tito barracks, remnants of the cable car, the Olympic Museum, the school in the neighborhood Ali Pašino, the Observatory building and the bobsled on the Trebević Mountain, trenches near the houses above Vraca neighborhood, and many others.

Destroyed building of the former Maršal Tito barracks and observatory building on the Trebević mountain. | Photo © Zoran Kanlić (2012)

Keeping in mind previously mentioned examples of war architectural heritage of Sarajevo, studying the work of Štraus and Woods, and from conversations with Štraus, I believe that to explore how it is possible to observe a ruined city as the one for all citizens, and not as the city for speculative constructing and manipulation with the war memories is a complex cultural and urban question.

This can also be read from the image of Sarajevo of today where after the war, reconstruction of the city has been observed and implemented as the construction of the new city, building even more square meters than we actually need, often neglecting socio-spatial relations and architectures built before the war, as well as a collective memory and life in the wartime city. The following text presents one part of the interview with Ivan Štraus on postwar reconstruction of his buildings, on Sarajevo in general, and about visions of architect Lebbeus Woods for the destroyed Elektroprivreda building.

Armina Pilav: Can you tell me which is your favorite building of those you built in Sarajevo, and why?

Ivan Štraus: It seems to me that you made a jump in time, as if nothing happened in the meantime. Only Sarajevo. At the beginning of my career I wanted to build houses in Sarajevo. That was my principal wish. I never had a wish to build in Europe and Yugoslavia. I even refused some offers to work in the notable Canadian bureau in Montreal. I also refused to stay in Addis Ababa after we finished construction of the designed complex for the General Post Office and Ministry of Telecommunication of Ethiopia. That was a surprise. Imagine you don’t know Addis Ababa or anything about it, you send your work by air mail, and you receive an unexpected first prize for an architectural project that allows you to continue to work on it and to construct the building. In Sarajevo, I wanted to build houses, which you can see and recognize by my design. Thus, it is difficult to choose among them which one is my favorite.

Armina Pilav: Even today, after all this time of existence of your built houses you do not know which is your favorite?

Ivan Štraus: After all this time and postwar reconstruction, with a note, actually reminding me, that every evil could serve towards something good. I would like to convey this thought to the almost four years’ war siege of Sarajevo when the Elektropriveda building was destroyed.

Destroyed Elektroprivreda office building. | Photo Elektroprivreda Archive (1992)

Is there anything more beautiful than to have the opportunity to build Elektroprivreda again, to correct some things that were built in a hurry? It could have been built better, but urgency of construction was conditioned by the availability of the construction materials. Importation of construction materials is today better than when I was building Elektroprivreda for the first time. For example, in constructing it for the first time, I had to install elevators from local producers. But for the reconstruction we imported elevators; everything was different. The renewed building I visited recently is different and better than after the first time it was built. This is because there was more money, more educated people and possibilities to import new technologies.

The reconstructed Elektroprivreda that you can see today is what I wanted to build before the war, but there was no time or resources for it. I planned different colors for it, but during Yugoslavia we couldn’t import aluminum in those colors. Before the war you could import construction materials only through the military company Unis and that’s why Elektroprivreda looked as it did before the war. I am glad that a fountain planned with the first project, when there was no money for it at that time, has been built within the reconstruction.

Elektroprivreda office interior during the war | Photo © Zoran Kanlić (1993)

Armina Pilav: I was wondering if the new colors of the Elektroprivreda were your choice or whether there is some political reason for it, whether the change of the political system and state could demand changes of the building aesthetics?

Ivan Štraus: The colors were my choice. I always had the ambition to introduce colors on the facades. I had great collaboration with the Elektroprivreda administration during the rebuilding process and as investors they respected all my decisions.

Armina Pilav: In which year was the reconstruction of UNIS towers started?

Ivan Štraus: It was in 2000 but, for political reasons, I was excluded from the reconstruction of the Momo and Uzeir (UNIS) towers. I worked only on the reconstruction of the Elektroprivreda building.

Armina Pilav: Did you use prewar drawings for the reconstruction of Elektroprivreda or did you have to make additional new drawings?

Ivan Štraus: I made new drawings.

Armina Pilav: How was it, running the process of the reconstruction?

Ivan Štraus: It is very difficult to explain. The director of Elektroprivreda at the time of reconstruction, Edhem Bičakčić with collaborators, agreed with me to remove everything what was above the second floor - literally to cut off ruined parts of the building: all of those architectural elements that were one on top of the other due to the destruction by rockets, tank shells and other destructive weapons. After the building remained clean up to the second floor, we started building the concrete structure. I had time in accordance with the investors to change some things in the new building with respect to the previous project.

Cleaning the ruined parts of the Elektroprivreda. | Photo © Zoran Kanlić (2000)

Armina Pilav: How did you document reconstruction of the Elektroprivreda building? Besides new drawings, did you produce some photos?

Ivan Štraus: No, we didn’t need anything else. We knew how it looked like before the war. There are photos.

Armina Pilav: The reconstruction process happened as you planned?

Ivan Štraus: There are other methods for the reconstruction of the buildings. I’ve had these principles for Elektroprivreda. For instance, I don’t agree with many colleagues who promote the idea that the building should be reconstructed as it once was: regardless of the general importance of the building or within the history of Sarajevo and Bosnia and Herzegovina, or for the history of architecture and what were these buildings before their destruction. According to many architects, everything about the postwar building should be as it was before the war, independent from demand or form its function in the future.

Armina Pilav: We talked a lot about the technical reconstruction processes. I will mention only Elektroprivreda, because you were involved in that reconstruction from the beginning. But, you didn’t say anything about your feelings. How does it feel to rebuild the same architecture?

Ivan Štraus: I don’t know.

Armina Pilav: What was your feeling? What does it mean to you, to construct technically the same architectural project two times?

Ivan Štraus: It means that we made a better building. It would be a tragedy to have made a worse building than in the first attempt. The third time would be even better, again a bit of black humor.

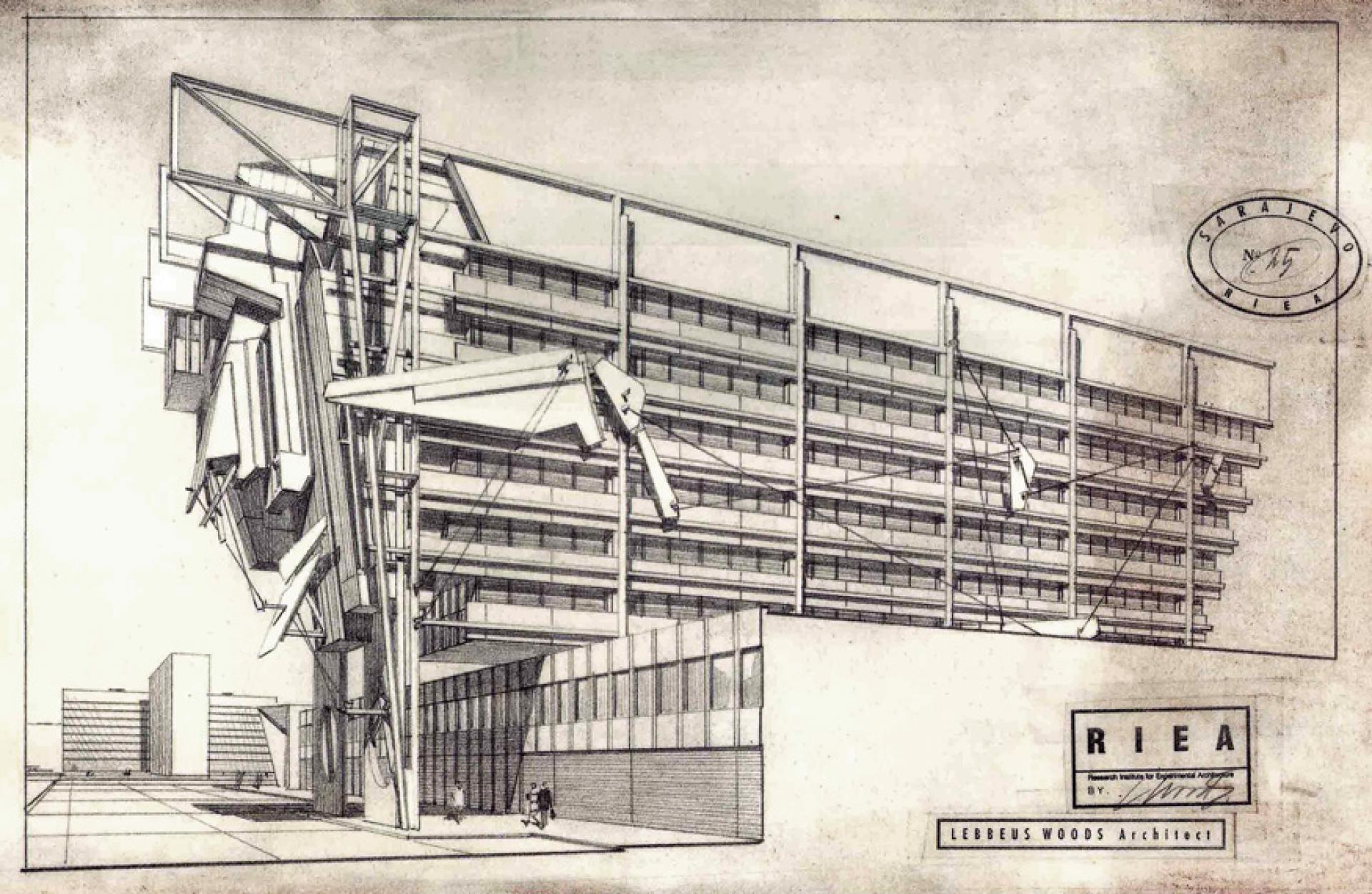

Lebbeus Woods proposed visions for postwar reconstruction of Sarajevo.The plan is presented in his books “War and Architecture” (1993) and “Radical Reconstruction” (1997) | Source © Lebbeus Woods

Lebbeus Woods visions for the reconstruction of the Elektroprivreda, Sarajevo and his thoughts about the war and architecture could serve as an integral methodology to the local architecture works about postwar reconstruction of unfinished city. Postwar construction speculation and building up glass buildings that, when finished, mostly remain empty, have contributed to the preservation of the war image of Sarajevo. Thus, the war in urban and architectural terms is still ongoing but without shells and bombs. Through the collection of micro-stories about Ivan Štraus, I was interested to learn about his collaboration with Lebbeus Woods. I was curious about possible intersections, juxtapositions of their two different approaches for the reconstruction of the destroyed Elektroprivreda, while comparing Woods’ radical proposal and Štraus’ choice to build again the same architectural form.

Armina Pilav: I assume that you are familiar with the work of Lebbeus Woods and his visions for the reconstruction of Elektroprivreda and Sarajevo?

Ivan Štraus: Not only with his work, I met Lebbeus personally in Sarajevo. He wanted to continue communication with me, but he showed up in a bad moment of my life. I was really in a bad mood in those days.

Armina Pilav: Was it during the war? I know that he came to Sarajevo at the beginning of the war?

Ivan Štraus: Yes, in the war. I have read his story about Sarajevo’s destruction and promoted his pamphlet War and Architecture inside the destroyed Olympic museum in 1993. And then our communication got lost somewhere.

Ivan Štraus and Lebbeus Woods in the destroyed Olympic Museum Sarajevo in 1993 | Photo via Lebbeus Woods

Armina Pilav: I am asking this because we know that Woods gave his vision for the reconstruction of the Elektroprivreda. Did you ever talk about it and did you see his sketches?

Ivan Štraus: I tried to show it to the people on the top positions in the Elektroprivreda company. I didn’t have a word for that. We should bring Lebbeus to explain his vision to them, but that was not necessary, because the result would be the same. They would just have moved it to the side and said “look what can be constructed”.

Armina Pilav: Lebbeus, like you, have had the attitude that the building from before the war, once destroyed, cannot be the same after the postwar reconstruction. If we look at his work, he is elaborating and presenting his position and ideas about postwar reconstruction differently than you. You have said before in our conversations: “with the reconstruction we cannot build the same building. Instead, with the reconstruction, we can correct some things, or some parts of the building can be constructed better than they were at first”. I believe that Lebbeus and you do not diverge in your thinking, but his and your postwar Elektroprivreda, esthetically and in architectural form, are different.

Ivan Štraus: I am more realistic. I think that he is not. When he was showing to me his drawings and explaining the vision, he saw the possibility to realize something like that in Sarajevo. He was saying that he would love to do it. I told him that I will do everything, but that he shouldn’t expect from me more than I can do.

Armina Pilav: It means that you were open for changes in the prewar design of the Elektroprivreda?

Ivan Štraus: Yes. I even made a certain kind of intersection of our drawings. I partially transferred his drawing on to my drawing. I sent it to him by mail, and wrote: “Lebbeus. Don’t be surprised, this is not your drawing, this is my drawing, we could make something of your proposal, but the dimensions should be reduced, because we cannot over construct it.” They should have this drawing in the Elektroprivreda archive, because it was in the meeting of the board of the directors. It was a paraphrase of a man who wanted to do us a favor. He wanted to try to build something different.

Ivan Štraus and Armina Pilav in Sarajevo. | Photo by Zoran Kanlić (2014)

Armina Pilav: Can you comment on the postwar reconstruction of Sarajevo after twenty years of war? Is postwar Sarajevo what we needed as citizens or perhaps the city could have been a bigger spatial experiment regarding to the urban and architectural forms, aesthetics, what Lebbeus Woods was also suggesting and what you were trying to show in the end?

Ivan Štraus didn’t reply to this question, but he said to me that he gave many interviews and himself wrote articles about the possible postwar reconstruction of Sarajevo for local and international newspapers, such as Sarajevo notebook and Libération from Paris.

After our first meeting, I continue to meet Ivan Štraus often and talk about the architecture, even if I personally still didn’t build any houses, but whenever I call Štraus to arrange our meeting he greets me as “good afternoon colleague”.

The first time he said that, I thought that we could never be colleagues, in view of our different architectural expressions: Štraus who was building more than writing, and myself who tends to write rather than build. Finally, I realized that my thoughts about not being a Štraus colleague were my own limitation.

Long conversations with Štraus based on our different architecture-related experiences made me rethink and become more interested in the cross-generational meeting of architects, even informal ones. We need to create space and find the time for open conversations and sharing of knowledge that include different generations, in order to understand better contemporary cities and the importance of the Yugoslavian architectural legacy with all respect to their original design and authors.

—

by Armina Pilav, photo by Zoran Kanlić

[1] Ivan Štraus, 1995. “Architects and Barbarians”, International Center for Peace, Sarajevo, p.136.

[2] Nedžad Kurto in the tekst Sketches of the City in the War, published in Warchitecture magazine, 1993.