Future Architecture Platform

In December 2015, an open call inviting architects and designers to submit innovative ideas on the future of architecture and cities as part of the newly established project Future Architecture Platform was advertised in various design websites.

Matchmaking conference at MAO in Ljubljana | Photo © Giodani Peter

This European initiative, originated from the Museum of Architecture and Design (MAO) in Ljubljana and bringing together a variety of architectural institutional bodies, is described as the first pan-European platform of museums, festivals, and producers whose goal is to communicate ideas on the future of architecture and cities to a wider audience and to promote emerging talents in this field. With almost 300 proposals submitted from all over Europe as well as from more remote continents, this new European platform was already promising to be a success in its early days.

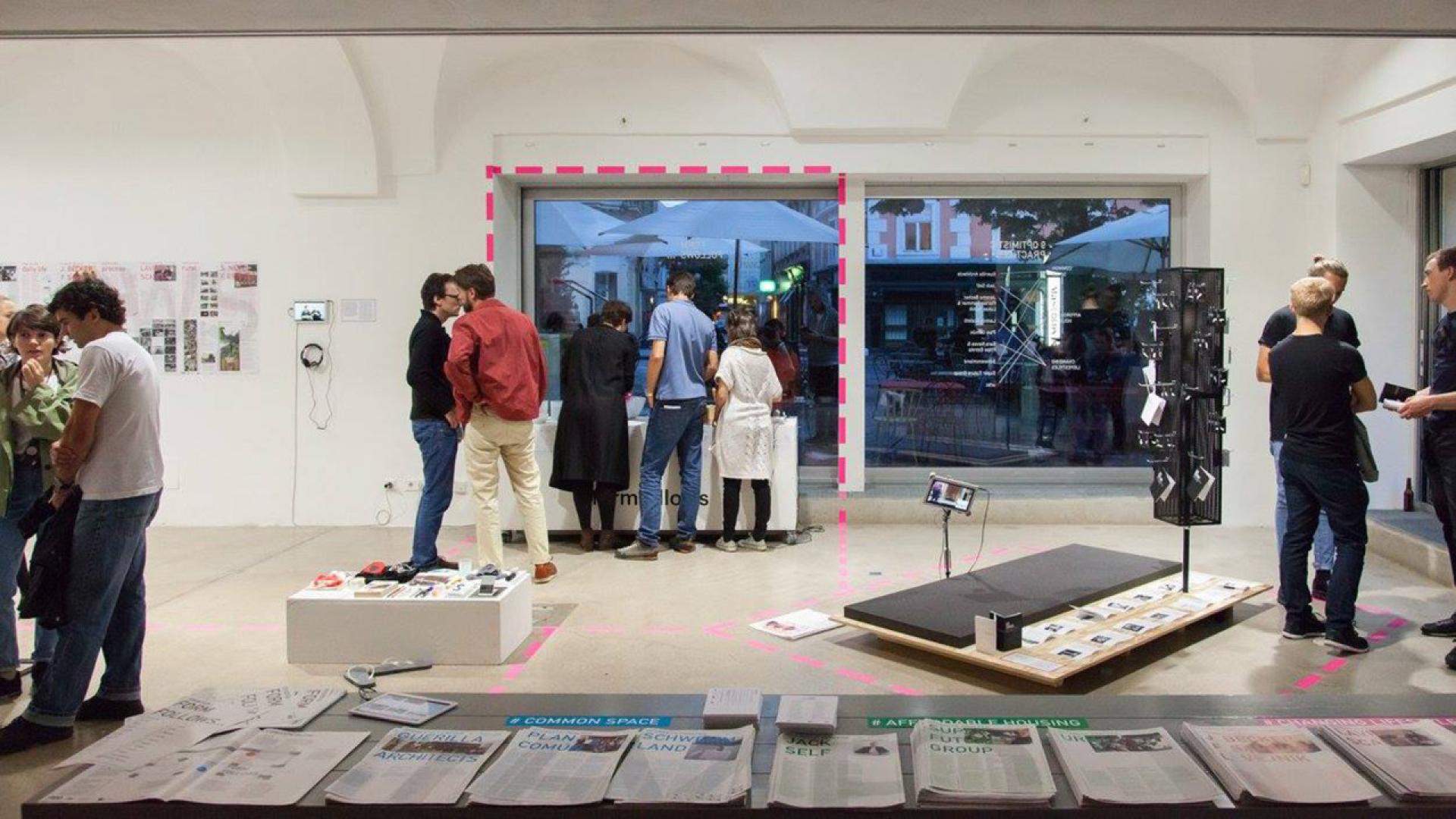

Future Architecture Platform conference at MAO in Ljubljana | Photo © Giodani Peter

Through a selection process led by a jury composed of platform members and of an online public, 25 finalists were shortlisted and invited to pitch their ideas at a two-day matchmaking conference in Ljubljana. At this event, both the selected participants and representatives of the various institutions had the opportunity to share opinions and make future arrangements. Although all the 294 proposals presented great visions for the future of city-making, the selected ones seemed to fully respond to the platform’s mission for innovative thinking and experimentation as well as to form a diverse body of work to present to the wider public.

Ranging from live experimental projects of building 1:1 structures to more theoretical analysis, from small scale interventions to more speculative future scenarios, all the selected proposals seem to share similarities, particularly in their position towards the contemporary urban condition. The projects are projections of possible scenarios that challenge the current status-quo by fostering debate and raising awareness of particular matters. In fact, one the stated goals of Future Architecture Platform is to make complex issues that are affecting our cities accessible to everyone as well as to highlight the distinct possibilities for dealing with them.

Zip City project at MAXXI Museum | Photo courtesy of MAXXI

It is with this objective mind that I have put forward my university project ‘Zip City: Houseless not Homeless’ for the open call. Zip City is an urban strategy programme exploring an alternative way of living in cities without a house whose primary goal is to contest the validity of the current housing system in London by encouraging debate around the possibilities of overcoming the crisis. This speculative proposal questions whether we still need a fixed dwelling to live in urban settings and if a possible solution to this problem lies in better understanding our desires for the comforts of a home in the context of our evolving necessities and technological advancements.

With 294 proposals, one would expect to encounter a wide variety of completely opposite approaches towards the way future architecture should be conceived. However, most of them hold strong social connotations. By giving the possibility of categorising the submitted idea through the choice of tags, most of the participants opted for using the ‘social’ one, suggesting that young architects and designers put people’s needs and social value at the core of their thinking.

Indeed, relating the future of cities to the notion of social reflects a shift in the way of conceiving and doing architecture: one that does not consider the production of the built environment as an isolated discipline that is solely faithful to its own discourses on form and function but as part of a wider socio-political agenda, where architecture both influences and is influenced by the context in which it is created. In thinking so, this new generation of designers turns its attention to everyday needs and entirely redefines the role of the architectural profession. Today, the future of architecture and cities seems to rely not only on the provision of carefully outlined physical spaces but increasingly on the design, implementation and integration of services and infrastructure.

One of the projects that perfectly depicts this expanded notion of architecture is Dotlinearchitects’ ‘Architecture for Refugees’, an online open source platform that focuses in sharing information and knowledge with the aim of improving infrastructural problems related to the current migrant crisis through the collaboration between refugees, activists and professionals. The initiative responds to this humanitarian issue by emphasizing the importance of enabling services such as WIFI and electricity to improve living conditions of people in the camps, reflecting how social innovation acts as a tool for development and integration.

Bioplarch project exposed at MAXXI | Photo courtesy of MAXXI

As a note, however, it is also worth mentioning that some of the proposals submitted to the platform are more detached from the social aspect of architecture and instead suggest that technology and innovative construction processes may present opportunities for the future development of our built environment. Linnea Vaglund’s ‘Biosynthetic Possessions’ is an interesting example of such an approach: the Swedish designer speculates upon a scenario that could potentially happen in 20 years time where people would be able to grow their possessions at home instead of being manufactured elsewhere by recurring to synthetic biology. Located between science and interior design, this proposal is a clear statement of a future where science and technology would allow to reinvent an entirely new conception of design and respond to our evolving aspirations of living.

Bioplarch on the left and Plan Comun’s Common Palces on the right at MAXXI Museum | Photo courtesy of MAXXI

To promote and share the work of the selected participants, the members of the platform have put in place a programme that would travel around various cities across Europe through a series of events of different nature such as exhibitions and talks, workshops, conferences and books. As part of this programme, I was invited to exhibit the project Zip City at the Haus der Architektur in Graz and at MAXXI museum in Rome as well as to a design workshop to respond to a specific brief on the future of the city of Ljubljana.

Themes for the exhibition Form Follows in Graz | Photo Thomas Raggam

At the Haus der Architektur in Graz, a carefully designed ‘Form Follows…’ summer exhibition curated by the Berlin-based architecture and research studio ISSSR displayed the work of 9 practices that were considered to have a spatial proposal that reflected an optimistic approach about the future of architecture and the profession itself. The similarities of themes were made evident in dissecting the exhibition into three main strands: Common Space, Affordable Housing and Changing Lifestyles.

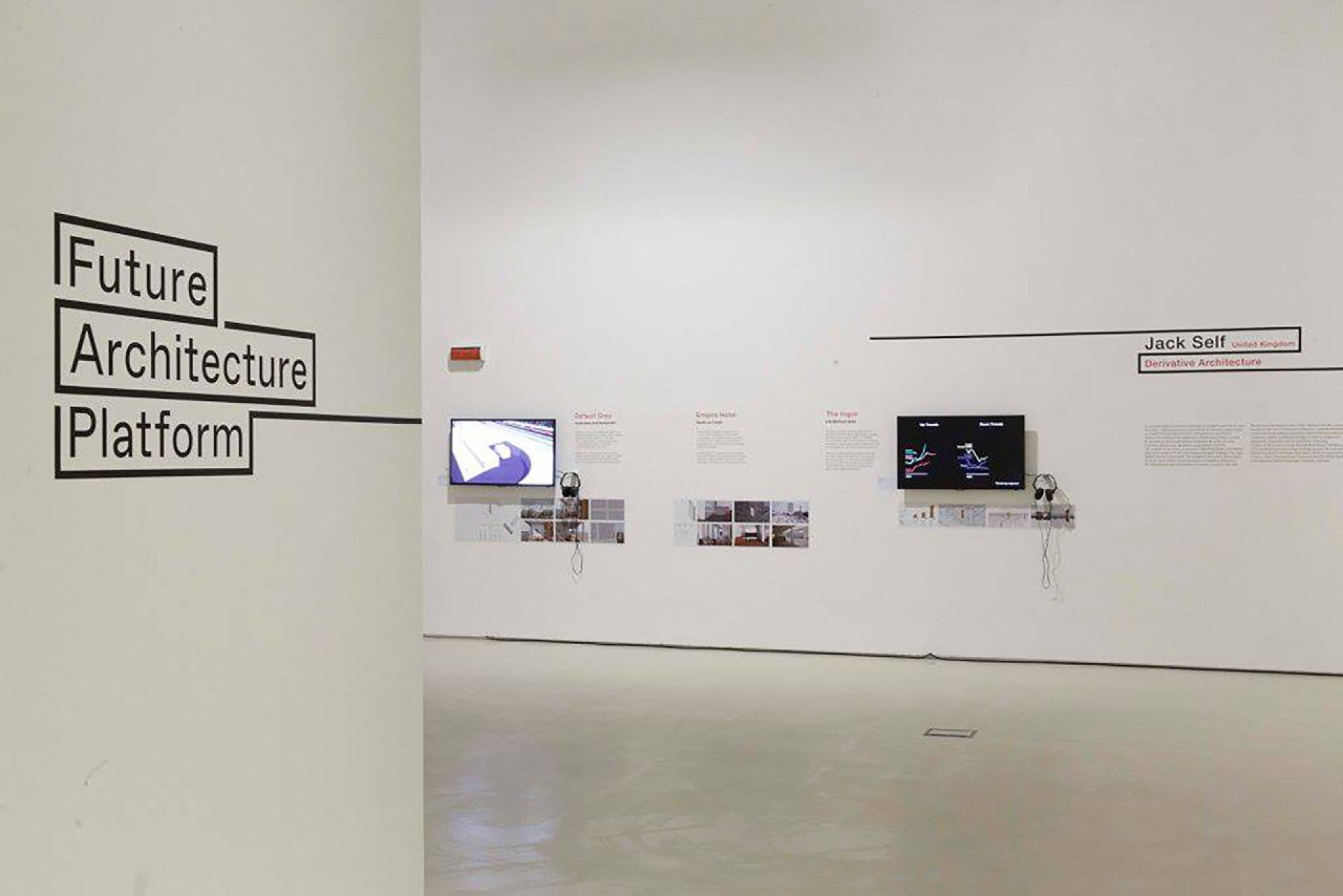

Jack Self’s The Ingot at MAXXI Museum | Photo courtesy of MAXXI

Despite not having being explicitly stated by the organisation, the ideas exposed as part of the exhibition ‘Future Architecture Platform’ at MAXXI in Rome also opted for participants that offered a more tangible response to the challenge they were addressing. It is by no coincidence that most of the exhibitors in Graz also received an invitation from MAXXI’s curators: Plan Comun’s ‘Common Places’ research project proposing new perspectives for re-introducing our long-compromised public spaces, Jack Self’s ‘Ingot’ offering a new housing model using financial tools or Urbz’s ‘No Future’ proposal inviting us to deal with the present condition and the tangible aspects of everyday life.

Inside Haus der Arkitectur in Graz | Photo Thomas Raggam

The highlight of the Future Architecture Platform at MAXXI was however the pechakucha sessions organised at the beginning of the summer, where the exhibitors as well as other five participants were invited to talk about their proposals in the museum’s courtyard.

Haus der Arhitektur in Graz view from the outside with Guerilla Architects’ van | Photo Thomas Raggam

Activities organised as part of the Future Architecture Programme are slowly coming to an end, with just a few more events scheduled until the end of the year, but there is a clear will of extending the platform’s schedule to the next years as well as to other locations. After all, the final mission of this very inspiring European project is to build commitment and bring ideas that will allow for a more sustainable and sustained future for our cities.

by Lavinia Scaletti