My Father The Designer

Pier Giacomo Castiglioni was an emblematic figure of the italian rationalism movement. With his two brothers, Livio Castiglioni and Achille Castigloni, he founded a design practice in Milano which went on to inspire generations of designers with their esprit paired with craftsmanship which they adapted sheer seamlessly to the constraints of serial production.

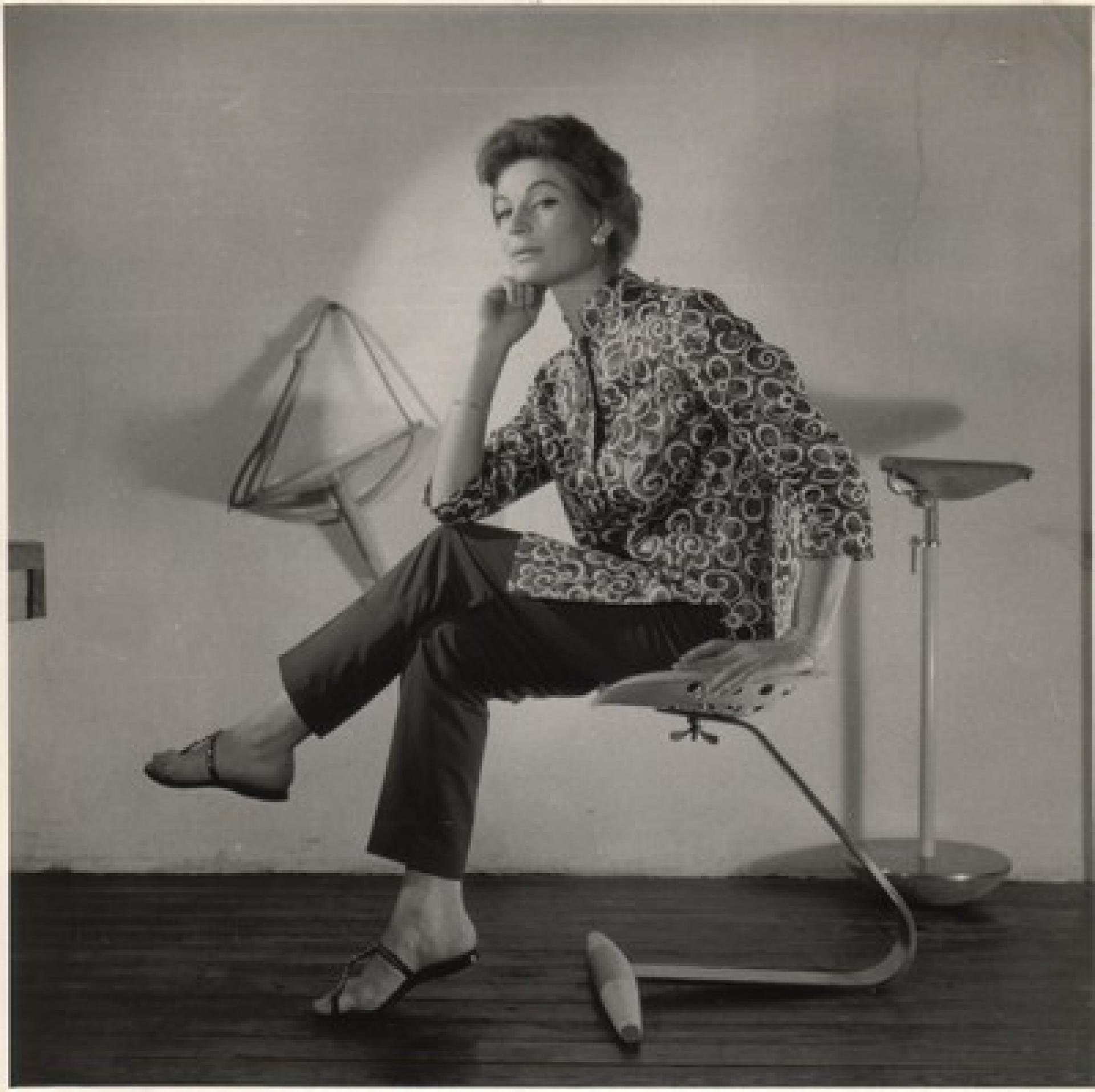

While Livio left the practice already in 1952, Pier Giacomo and Achille worked together until Pier Giacomo’s death in1968. Achille continued to work as an industrial designer and professor at the Milan Politecnico. To retrace Pier Giacomo’s approach and contribution to modern design, we spoke with his daughter Giorgina Gastiglioni, also an architect.

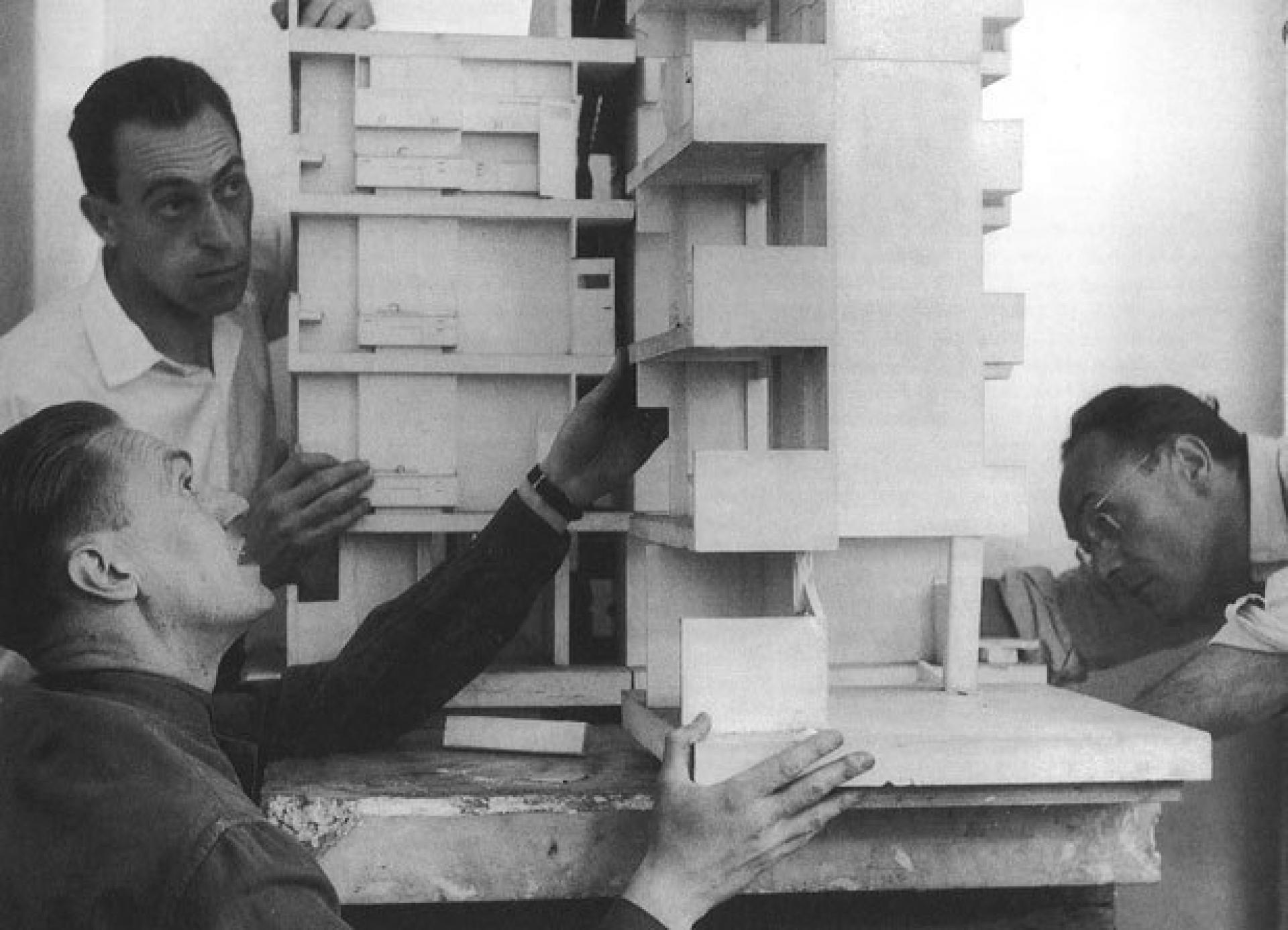

From left Achille, Pier Giacomo, and Livio Castiglioni | Photo via Corriere

Giorgina Castiglioni: My father as well as my grandfather [the sculptor Giannino Castiglioni] was somebody who always wanted “to do” things. It was his philosophy to act, create, observe carefully since his days in school at Brera [a district in Milan]. The setting there was artistic with a strong emphasis on achieving results which might have been one of the reasons why he followed in his father’s footsteps [to work in a creative profession]. He immediately enrolled in the faculty of architecture in Milan and graduated “cum laude” at the Politecnico di Milano in 1937.

When [my father] Pier Giacomo was drawing or modeling with clay, nobody ever interfered, everybody watched with admiration. However, once while preparing a design for a tissue manufacturer; I was intrigued to introduce a variation of my own. It was a great satisfaction when the design was produced in the version I conceived, a victory! I still keep this piece with me, it is just as I wanted it!

[When I think of the Castiglioni brothers] I think of a jam session at a jazz concert where every player interprets a predetermined set while the resulting piece gains its success from the synergy of unique interpretations of different converging instruments. This is what we must understand to grasp the success of the Castiglioni brothers. Everyone had his own instrument to interpret design. Two architects who are able to collaborate, for example with drawings, make a fantastic group work.

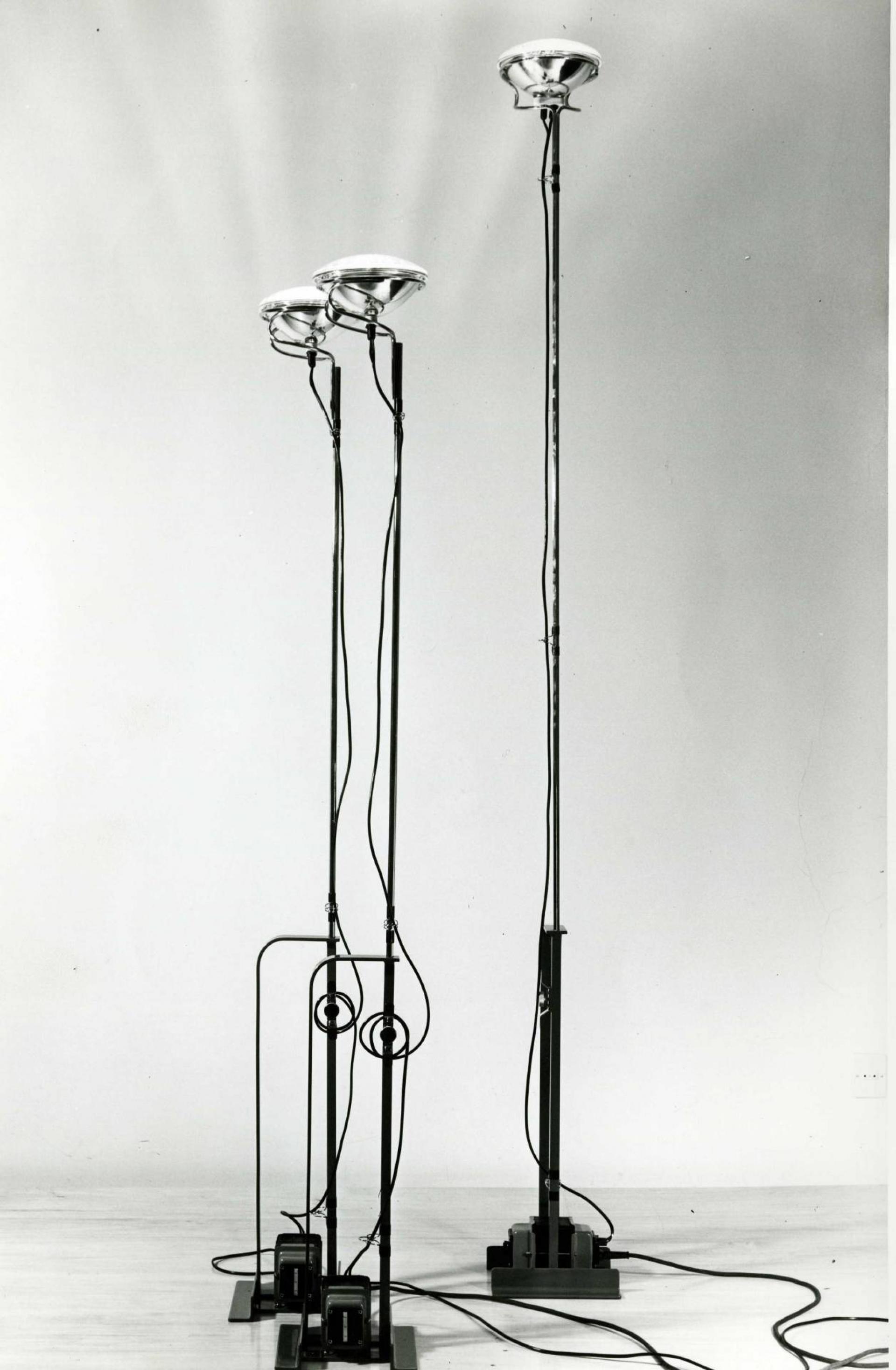

The Arco floor lamp for FLOS (unplugged), one of the two brothers’ masterpieces.

Could you describe the relationship and the influence between Pier Giacomo and other architects and graphic designers of his time?

GC: Pier Giacomo Castiglioni taught Architecture Composition from 1938 at Politecnico of Milan. His numerous acquaintances inside and outside university allowed him to exchange views with renowned professors of the time: Renato Camus, Piero Portaluppi, Gio Ponti, and Ernesto N. Rogers by whom he was highly valued. Through his work at the Triennale di Milano in the form of exhibitions and installations he was able to come across inspirational design work which laid the groundwork for future collaborations. He selected Italo Lupi to become part of his group of assistants for the course “Disegno dal vero e relief” [Live drawing]. The same group of architects and graphic designers were chosen by Achille Castiglioni for his academic tenure after Pier Giacomo’s death in 1968. These collaborations continued until 2002 and beyond. From the graphic designers I remember among others Max Huber from Switzerland, Giancarlo Illiprandi aka Ili, Italo Lupi and Pino Tovaglia.

Pier Giacomo Castiglioni presenting the Viscontea and Taraxacum lamps to Marcel Breuer in Milano, 1963 | Courtesy of Giorgina Castiglioni

Your father was closely involved with theoretical aspects of design as well as its production; how did that influence his design process?

GC: My father’s work in the field of architecture and design brought about a new culture and approach which distinguished him from the protagonists in Milan at the time. This is apparent in his projects has been critically reviewed in successive times. The theoretical foundation can be retraced to an article in the magazine Edilizia Moderna n. 85 (1965), where Castiglioni brothers responded to a series of questions and subsequently laid out their integral design approach. had an interview about their work process.

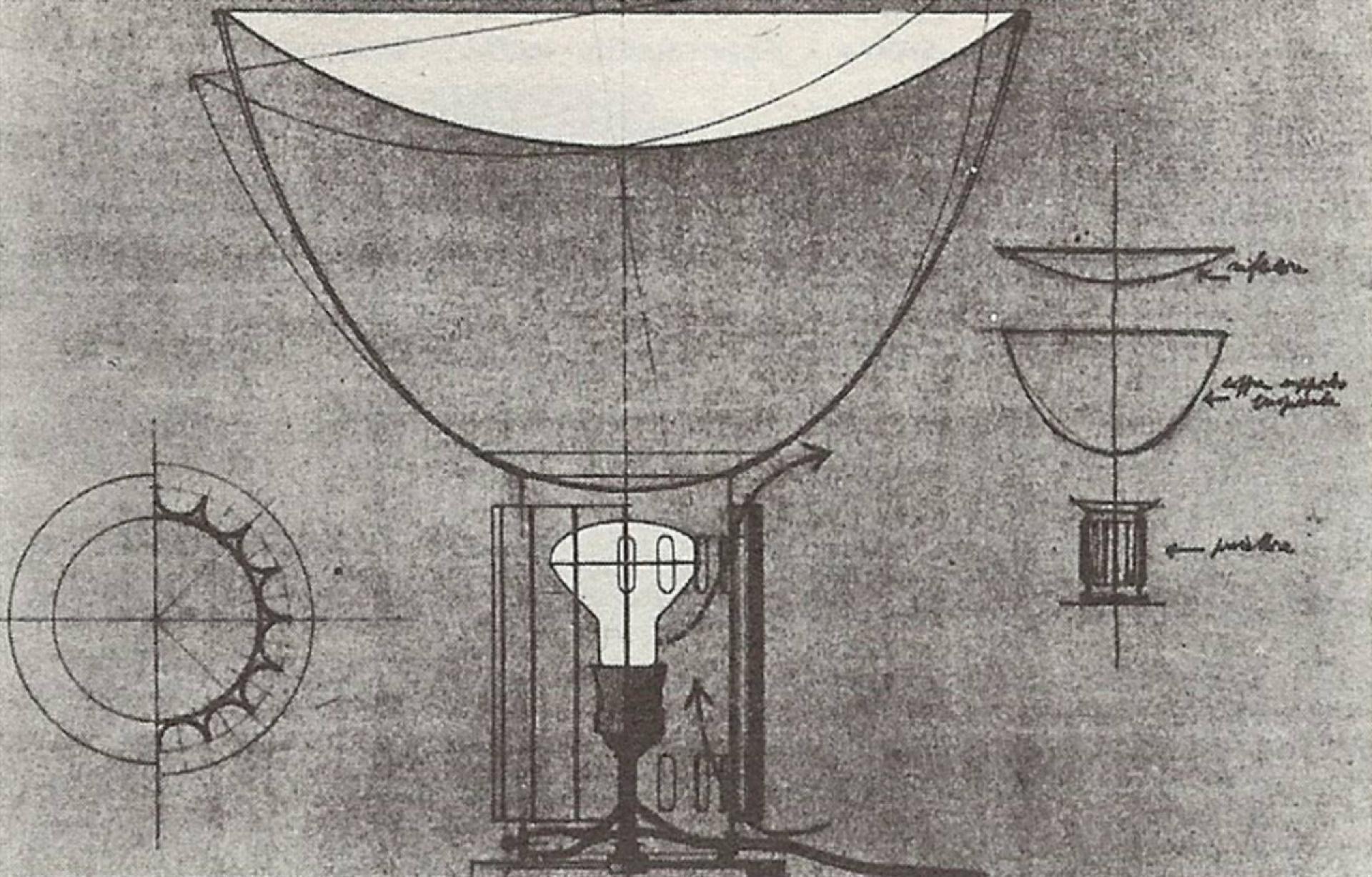

Sketch of Taccia Lamp, 1960s | Photo via Pensare per immagini

The Castiglioni brothers were two personalities with the same mindset. Is it possible to trace the original contribution by Pier Giacomo Castiglioni through his drawings, personal project notes, specific design choices?

GC: My father used to frequently adopt drawings as an expression of his thoughts to convey concepts in a clear and immediate way. This wasn’t an innate skill, but was gained through experience over time (which I repeat often). Through continuous exercise he expressed his ideas simultaneously through thinking them and through the flow of his pencil. His original drawings were later, 20 years after his death, reworked by Achille, but completely differently in their graphic expression from those of Pier Giacomo. His stroke, clean, precise, direct (from the mind to the hand) is easily recognizable. However, we must recognize Achille’s showmanship who knew how to conquer the public as well as students who he enchanted and taught in unusual ways.

Pier Giacomo and Achille testing their Taccia Lamp, 1960s | Photo via Abitare

The decontextualisation of the consumer good is the ‘modus operandi’ of Castiglioni’s timeless design. What was the material and intellectual contribution of Pier Giacomo in the construction of models such as Mezzadro, Arco and Taccia?

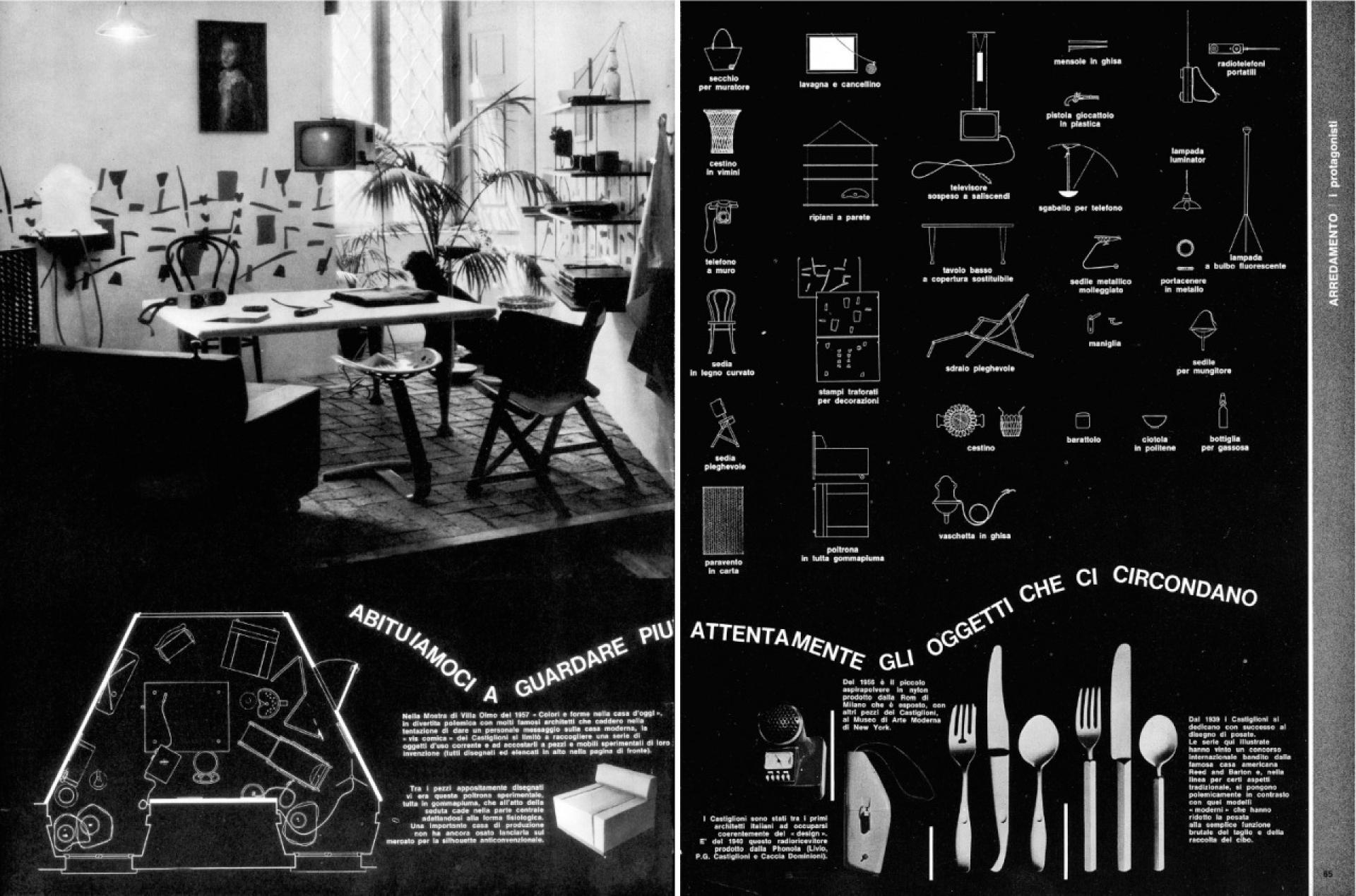

GC: My father was a very good observer. Everything surrounding him was carefully analyzed. From switches to the simplest things, such as tractor seats (Mezzadro) to car lamps (Toio) as well as many interesting objects collected over the years. [These objects] formed a distinctive ensemble which both architects brought to the studio where they remained to create a truly singular collection. The first event which showcased these routines was the exhibition at the Villa Olmo (Como) in 1957 (see Canella’s article in the magazine Fabtasia Anno V of July 1963). Often these objects were “reused” in completely new contexts giving rise to new unexplored investigations. An example for this decontextualisation is the Toio lamp which is reminiscent of a fisherman’s rod.

Villa Olmo exhibition description about the modern housing | Courtesy of Giorgina Castiglioni

Toio, the translation by Achille and Pier Giacomo Castiglioni for the English word toy, with special linguistic divertissement that lets them appropriate a foreign word and make it familiar and meaningful. Really does have the magic of a toy for the adult world. | Photo via Ylighting

The cantilever Mezzadro, a tractor seat mounted using a wing screw on a curved steel spring and with a netting needle (a birch weaving instrument) as base | Photo via The Red List

What was the relationship between detail and entire project in its complexity in the light of a production that used standardised materials?

GC: An example is the Snoopy lamp which was born out of a conversation with Ms. Gandini and a hand drawing by Pier Giacomo which immediately laid out the idea for the project’s core. In fact, the manufacturer and the designer interact through an integrated process. It starts with the design [and continues with] production and consumption; a recycling philosophy was not included in the design, and this is why the industrial pollution today has to be curbed by designing in a sustainable way.

Snoopy lamp and Achille and Pier Giacomo Castiglioni at their studio in Corso Porta Nuova, 52. 1967 | Photo via 3nta

Can you tell us something about the Splügen Bräu brewery project?

GC: Splügen Bräu is today known as a project by the Castiglioni brothers, but without being associated with an existing type of restaurant. Spluga is also an innovative chair. In London at that time a certain [restaurant] venue was rampant: Wimpy. The owners of this chain were very interested in the Castiglioni brewery and the architects were contacted to discuss a new [location for the] chain in Florence at Piazza della Signoria; it was 1966…

Neoliberty furniture with tables placed on different levels and sofa that remind to the old train carriages, 1961 | Courtesy of Giorgina Castiglioni

Did you notice any changes between your father’s production at the beginning of his career and later on?

GC: Always surprising: I recognize the way may father works, his design and his human trait, he was determined and remained so over time.

Can you tell us something about Pier Giacomo Castiglioni and his concept of innovation?

GC: It suffices to think of the exhibition at Villa Olmo (Como) in 1957. A & PG Castiglioni project was entertaining, in my opinion it was their most interesting one. [It was] innovative as Michela Gazziero tells us in the article “Ambiente di soggiorno: Villa Olmo, 1957” published in “1913-2013 Pier Giacomo 100 times Castiglioni”, Ed. Edibus, 2013.

At the same time your father and his generation have experienced the discomfort of war: do you believe this starting point has somehow influenced the design of Pier Giacomo Castiglioni and other post-war designers?

GC: In post-war years there was a great frenzy for reconstruction that led to the economic boom of the 1950s; the Castiglionis resumed their work in their studio in the Corso die Porto Nuova, 52 in Milan with great optimism. At the Milan fair which took place very year in April, they designed installations for pavilions of major companies including Montecatini, ENI, AGIP, RAI and others. Regarding RAI, they followed the company’s evolution: the advent of broadcasting, the birth of television, the various television shows RAI produced. The spaces [the Castiglionis created] were unusual and sophisticated. From early on the architects involved used drawings to communicate, Max Huber the first among them. These spaces, like Montecatini’s, left everyone breathless year after year! The project of the last exhibition in 1967: a triumph!

Castiglioni brothers with graphic designer Enzo Mari set up the RAI pavilion with modular elements that allow indoors and outdoors fruition for the 42nd Milan Fair in 1965. | Courtesy of Giorgina Castiglioni

Exhibition for Montecatini company in 1955 shows the room for the agricultural pesticide. Graphic by Michele Provinciali | Courtesy of Giorgina Castiglioni

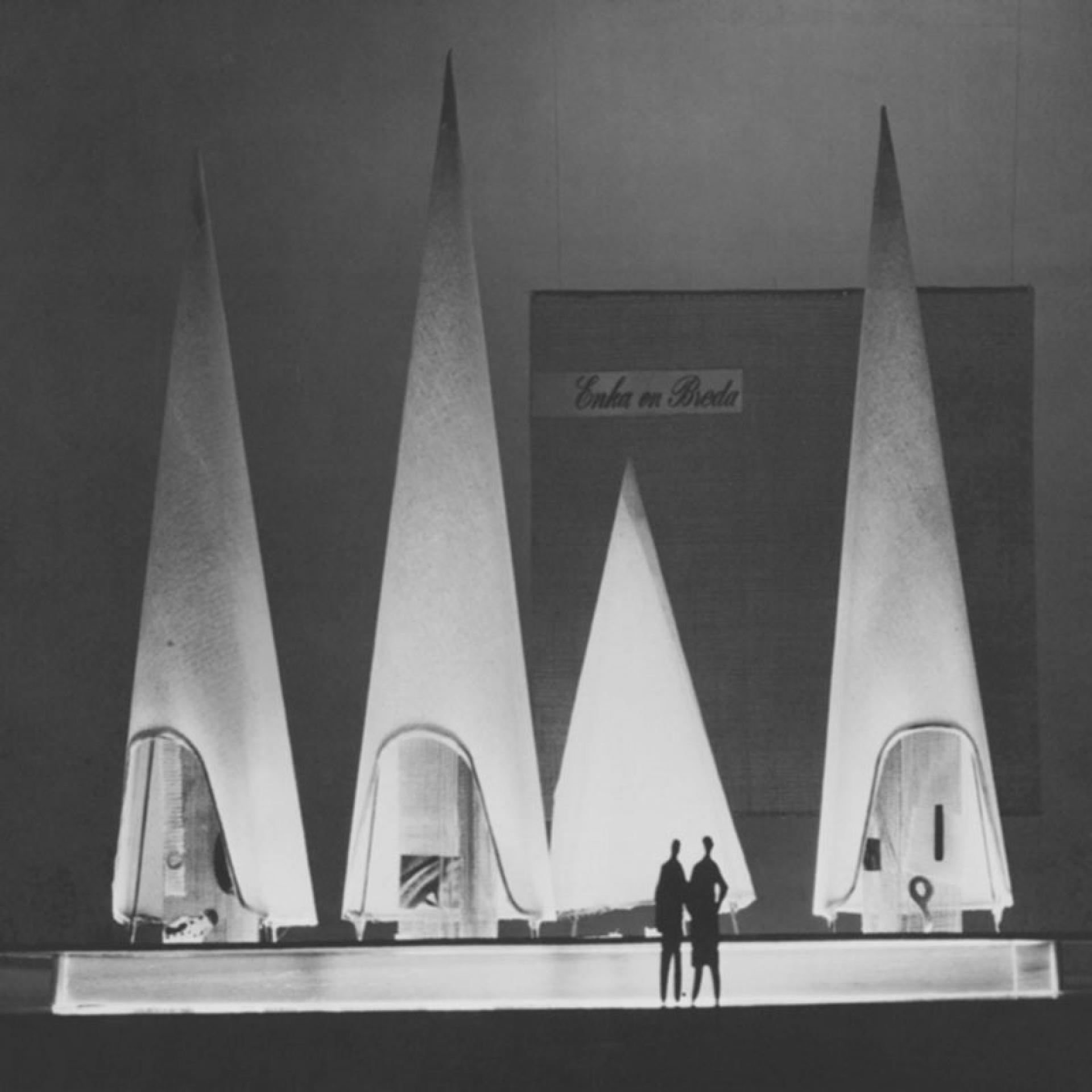

Model of the stand Enka en Breda for a Belgian textile exhibition in 1955 with the graphic of Michele Provinciali | Courtesy of Giorgina Castiglioni

Do you personally think that architecture is still useful to society as a whole, or do you think it is just a succession of ephemeral novelties?

GC: It is extremely useful with regard to the aspect of experimentation which leads to the evolution of architecture itself. The reevaluation of suburbs is currently an urgent problem. It is also extremely interesting to redesign unused spaces which exists due to the demise of large urban factory buildings. An example is my project “A Green Canal in the City”, presented on the occasion of a competition of the Comune di San Donato Milanese.

by Daniele Ronca and Alex Karpov