FOMA 40: Demolished Masterpieces Of India

The status of architectural heritage in India is either demolished, dilapidated, or being fought for, by concerned citizens, architects and conservationist but the definitions remain blurry and more and more buildings are being taken off the heritage list each day to make room for new development projects.

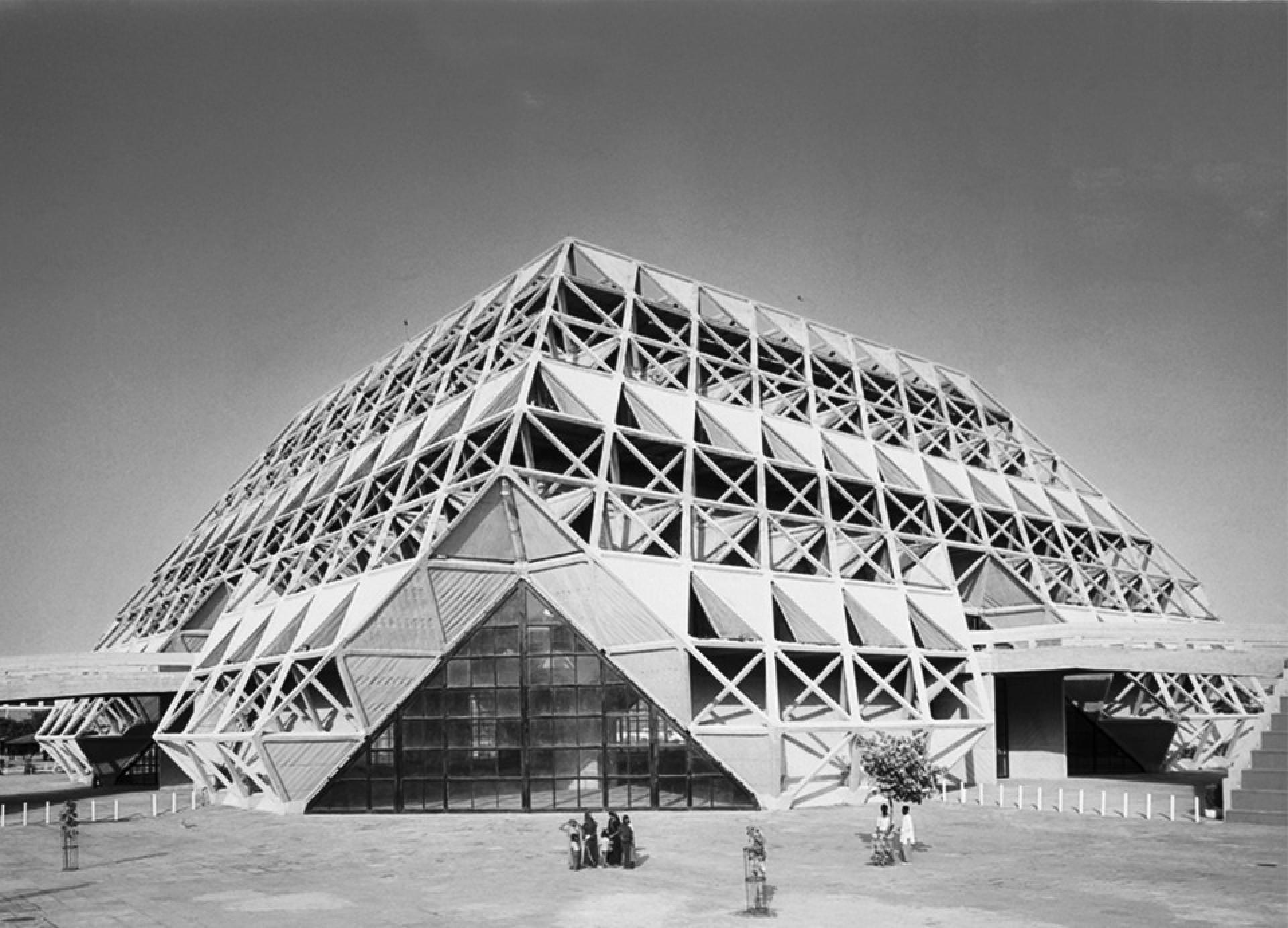

The Hall of Nations by Raj Rewal (1972) | Photo via livinspaces

From the government initiated social housing projects, which answered the massive housing crisis in post-independence Indian cities, to the WHO Headquarters in Delhi (1962) and the Hall of Nations (1972) that was built to celebrate 25 years of India’s independence from the British Raj, are just a few examples of such great loss.

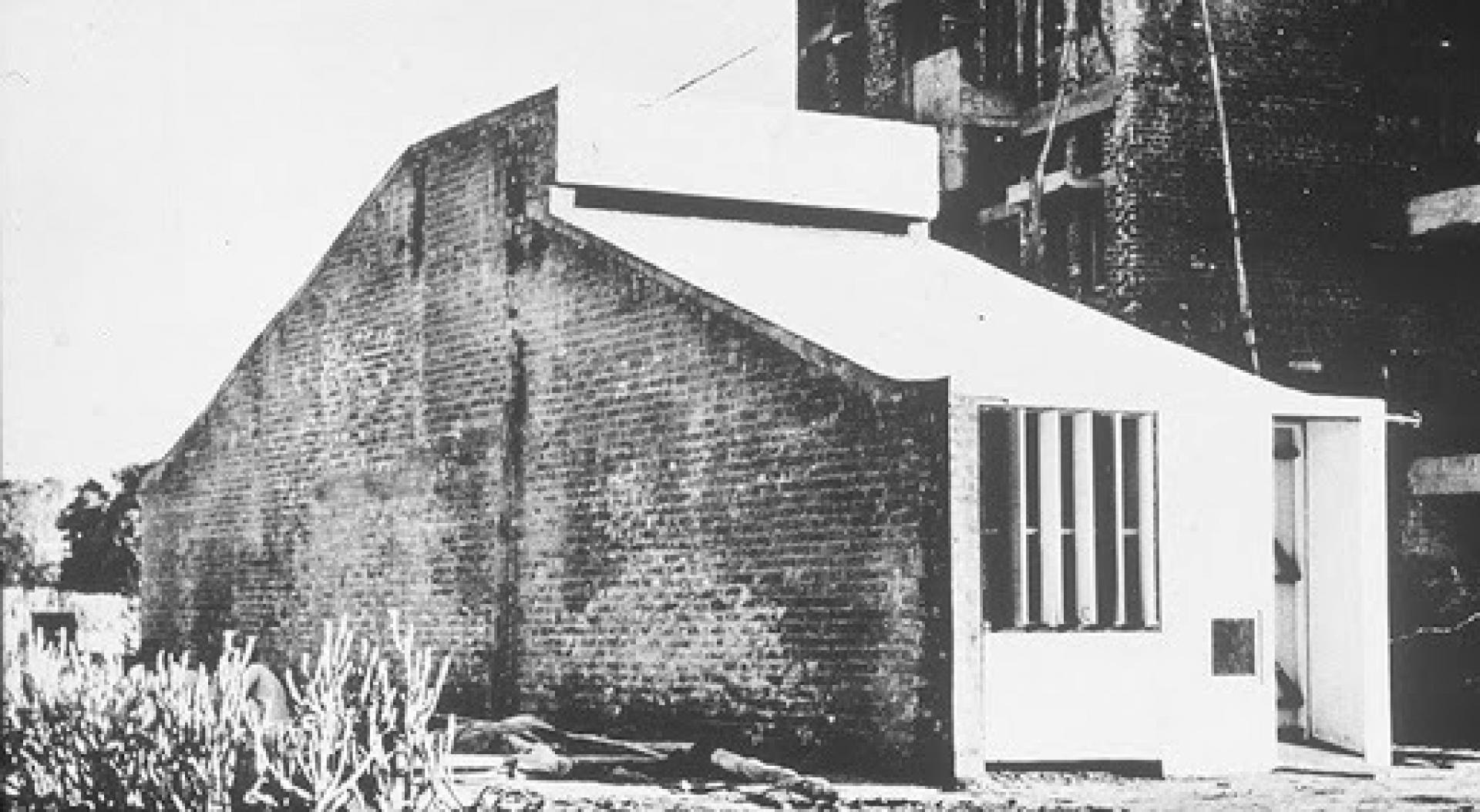

Correa’s Tube House prototype for the Gujarat Housing Board’s low cost housing competition in 1960. | Photo via Charles Correa Archive

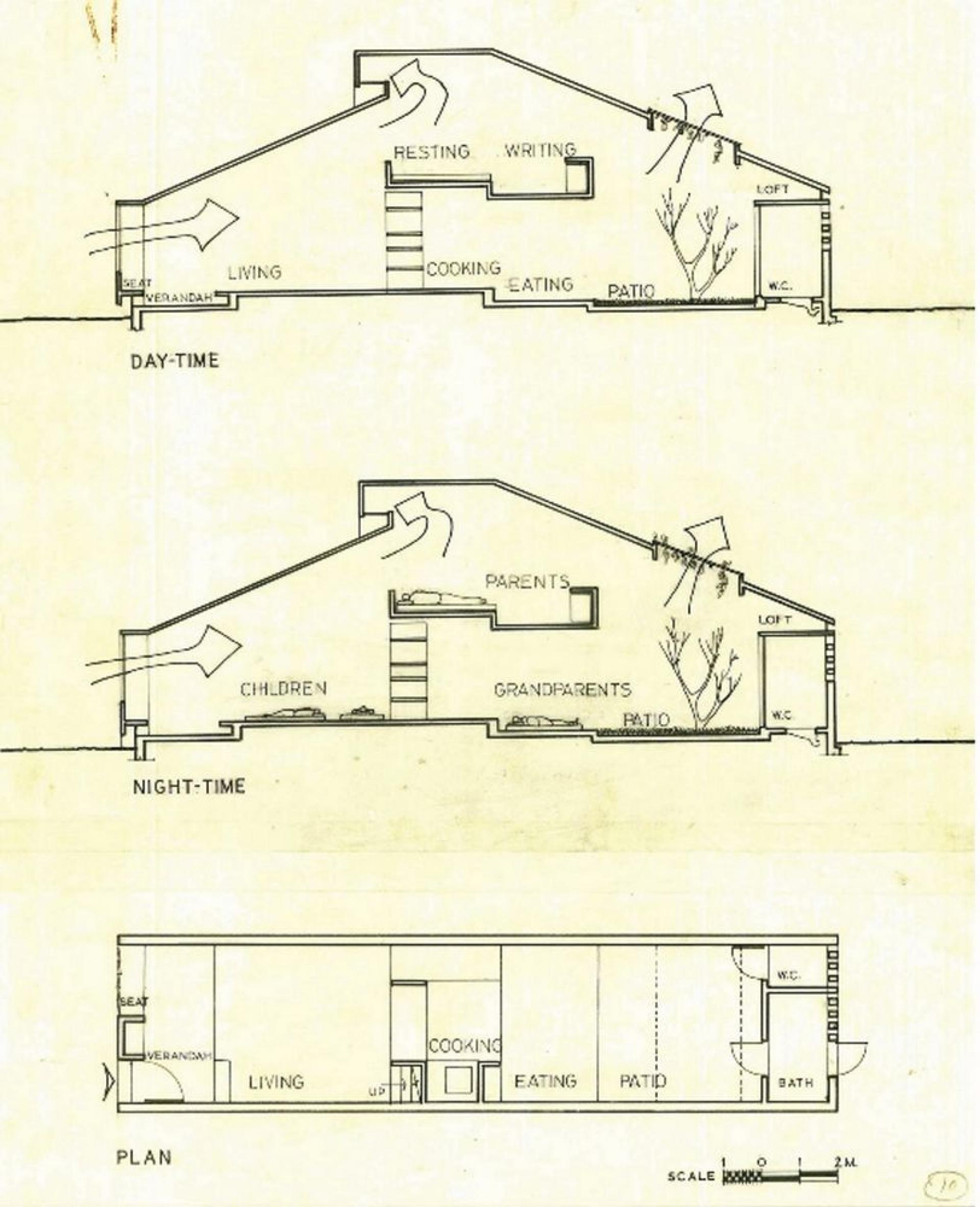

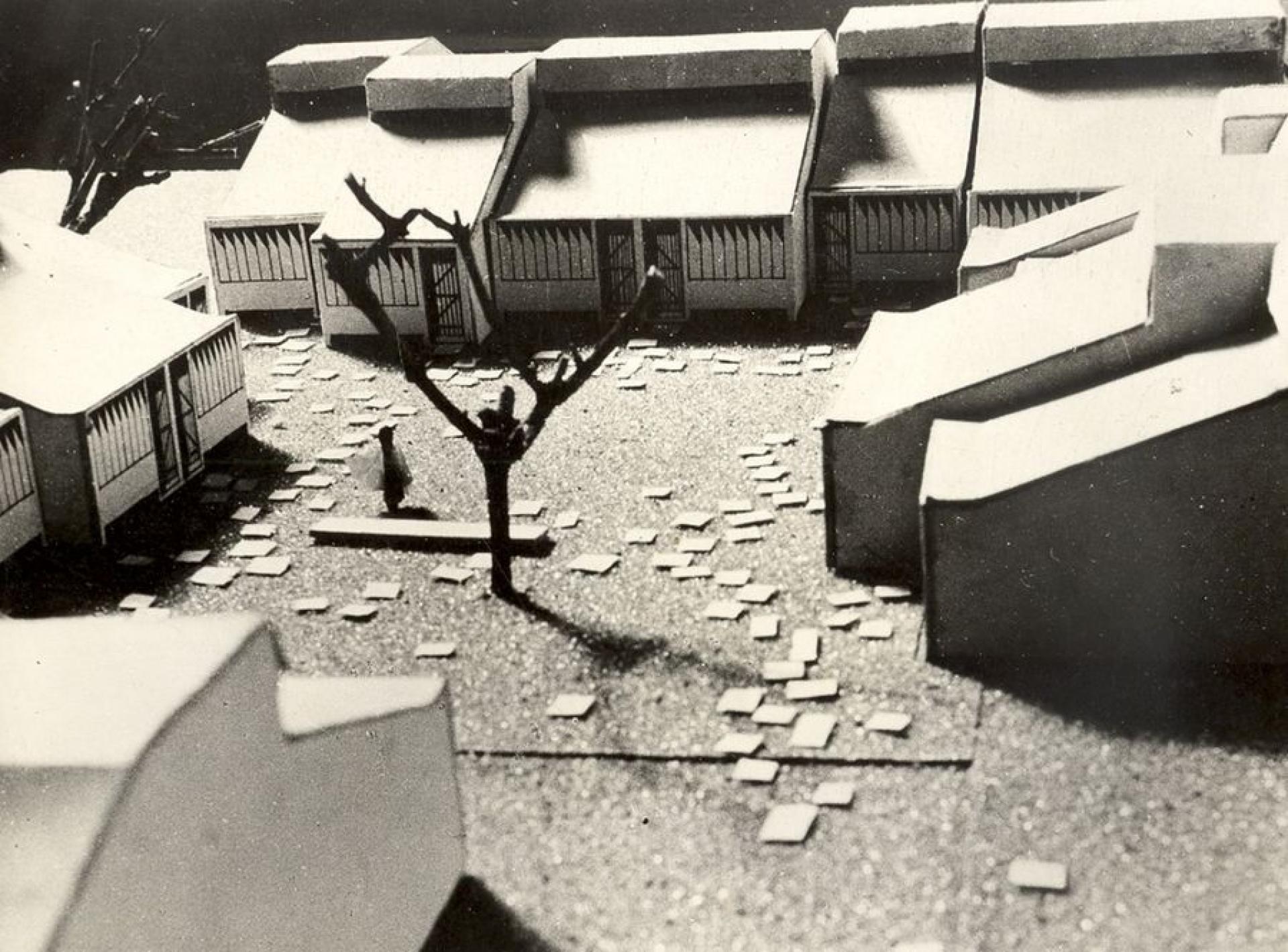

In 1960, the Gujarat Housing Board initiated an open competition to gather new ideas in the realm of low-cost/affordable housing. Inspired by the ‘windscoop’ houses of Iran or Alhambra in Spain, Indian architect Charles Correa developed a low rise, high density layout with at most attention to climate and comfort. The Tube house unit with its sloping roof and adjustable louvers used the conventional airflow to naturally ventilate the house. An open floor plan with raised levels created privacy. This unit was the only one built by the housing board as a prototype. Built at the height of the Indian socialist movement, the Tube House cemented Correa’s position in housing design in the country and allowed him to try out many of the theories of low rise-high density clustered incremental housing that he developed further in Belapur housing, Mumbai and PREVI Experimental housing project, Lima. The Tube House was demolished in 1995.

Drawings of the Tube House explaining different space for different activities and users. | Photo via Charles Correa Archive

Cluster of Tube houses with ‘wind-scoops’ for ventilation and community central courtyards. | Photo via Charles Correa Archive

Based on the spatial, material and climatic methodologies developed during the Tube House, Correa went on to try them in an another of his houses, the Ramakrishna House built for a mill owner in Ahmadabad. Whether it was low-cost social housing or a house for a wealthy mill owner, Correa was able to elegantly merge local materials and traditional building techniques while maintaining a modern aesthetic. Placed at the northern end of the plot to maximize on the garden, the house is a series of load bearing walls punctuated by interior courtyards and windscooping canons. Victim to the real estate boom, the Ramakrishna House was sold to a developer and the building was demolished in 1996 to make room for a commercial building.

Ramakrishna House | Photo © Peter Serenyi, MIT Libraries

Next on the list of recently demolished is the WHO Headquarters in Delhi. Built by architect Habib Rahman, who was one of the pioneers of Modernism in India. His life long career in government and public works department has given Delhi and Calcutta some of its most iconic buildings. The WHO headquarters was a three-year long project, completed in 1962. Rahman was a senior architect with the Central Public Works Department (CPWD) at the time. The building was inaugurated by Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru.

The building remained a city landmark for Fifty seven years, before the six-storeyed structure was pulled down by the National Buildings Construction Corporation in July of 2019. The NBCC claimed that the building was old and fell under a seismic zone. The corporation will construct a new building for the WHO that will have around 17 floors.

Demolished WHO building in Delhi. | Photo via Habib Rahman Archives

Another one amongst Rahman’s masterpieces being forgotten and razed are the ’Rahman Type Flats’ in Netaji Nagar, Delhi (1954-56). After taking cabin in 1947, Nehru went on a massive building and infrastructure spree. Housing had to be built for the new government employees that were migrating to Delhi, and also to rehabilitate the huge number of people that had been displaced during the partition of the country. Besides housing also markets, cultural centers, cinemas and office buildings were built at that time. At this point Rahman’s Gropius and Bauhaus training came in handy. Rahman was asked to organize the International Exhibition on Low Cost Housing in 1954. The exhibition got architects and engineers from all over the country to take part in building sample prototypes and publishing detailed drawings, estimates and materials. Rahman’s bright, well ventilated, simple two story and two room houses became a prototype for government staff housing. They came to be known as “Rahman Type Flats” and were repeated in thousands across the country. One such example of it was the government staff quarters in R.K.Puram, New Delhi completed in 1959. It housed government employees and their families for decades before they were finally demolished in 2018 to make way for high rises, which would trade public land to private entities.

Habib Rahman CPWD housing 1954 | Photo via Habib Rahman Archive

Demolition of “Rahman Type Flats” photographed by Habib Rahman’s son Ram Rahman on 28th June 2018. | Photo via architexturez

And lastly the one for which the world cried. From Pompidou Centre to MoMA in New York to the entire architecture community in India raised opposition to the demolition of The Hall of Nations in Delhi. In the 1970, Prime Minister Indira Gandhi called for entries to design a large exhibition complex which would exhibit airplanes and satellites to commemorate 25 years of India’s Independence. Young architect Raj Rewal’s entry not only got him the project but also curiosity and appreciation from the world. Rewal recalls the time when Buckminster Fuller came to the site and was stunned by Rewal’s massive space frames in concrete making the fabric of the exhibition hall. Inspired by the traditional Indian Jaali (perforated screens), his space frame education in Europe and Le Corbusier’s sun breakers as an extension to his building façades in Chandigarh, Rewal here let the space frames itself become the walls and the roof of the exhibition halls. Engineer Mahindra Raj explains how space frames everywhere were being done in steel at the time but India did not have the quality and the fabricators for steel sections for a project of that scale and importing steel sections from abroad to build this symbol of India’s growth and progress was not an option. 45 years later in 2017, the Hall of Nations was pulled down by half a dozen bulldozers that worked overnight to demolish this masterpiece of post-independence architecture in India making way for a “new state-of-the-art convention centre and exhibition centre.”

Architect Raj Rewal and structural engineer Mahindra Raj created the Hall of Nations in 1972. | Photo via livinspaces

In conversation with the Quint after the demolition, Rewal explains, “In 1972, the Hall of Nations and Industries was symbolic of an achievement by young architects in a newly-independent India, creating a style, which could be constructed with limited means, yet be uniquely Indian.”

Architecture Live quoted Rewal: “[[Hall of Nations]] was a great feat of art and architecture… it was a symbol of what very ordinary people can do. 500 families worked on the site; there were no canteens, no crèches, no helmets, and the work went on for a very long time. The structure was built from hand-poured concrete, and was labour intensive; the credit does not only belong to the architects and the engineers, but also to these people – because it was their achievement, to have created something through such simple methods.”

These statements of Rewal aren’t only true in case of the Hall of Nation but for all of India’s modern heritage that is slowly disappearing along with its history.

Zahara Chhapra is an architect and researcher from Mumbai, India. Having recently completed her Masters in Design Research from the Bauhaus in Dessau, Zahara now resides in Berlin and is a researcher and editor with Architectuul. Her interests lie in the spatial and political agency of architectural and urban actors in the everyday life of the city.