FOMA 18: Building Up the Screen - The Rise and Fall of the Mexican Cinema Spaces

In today’s digital era, its is difficult to think of the experience of going to the movies as something related to a grand design or glamorous spaces, but rather a generic and multipliable model of the contemporary movie theater, a globalized phenomenon where the experience is limited to the world on the screen.

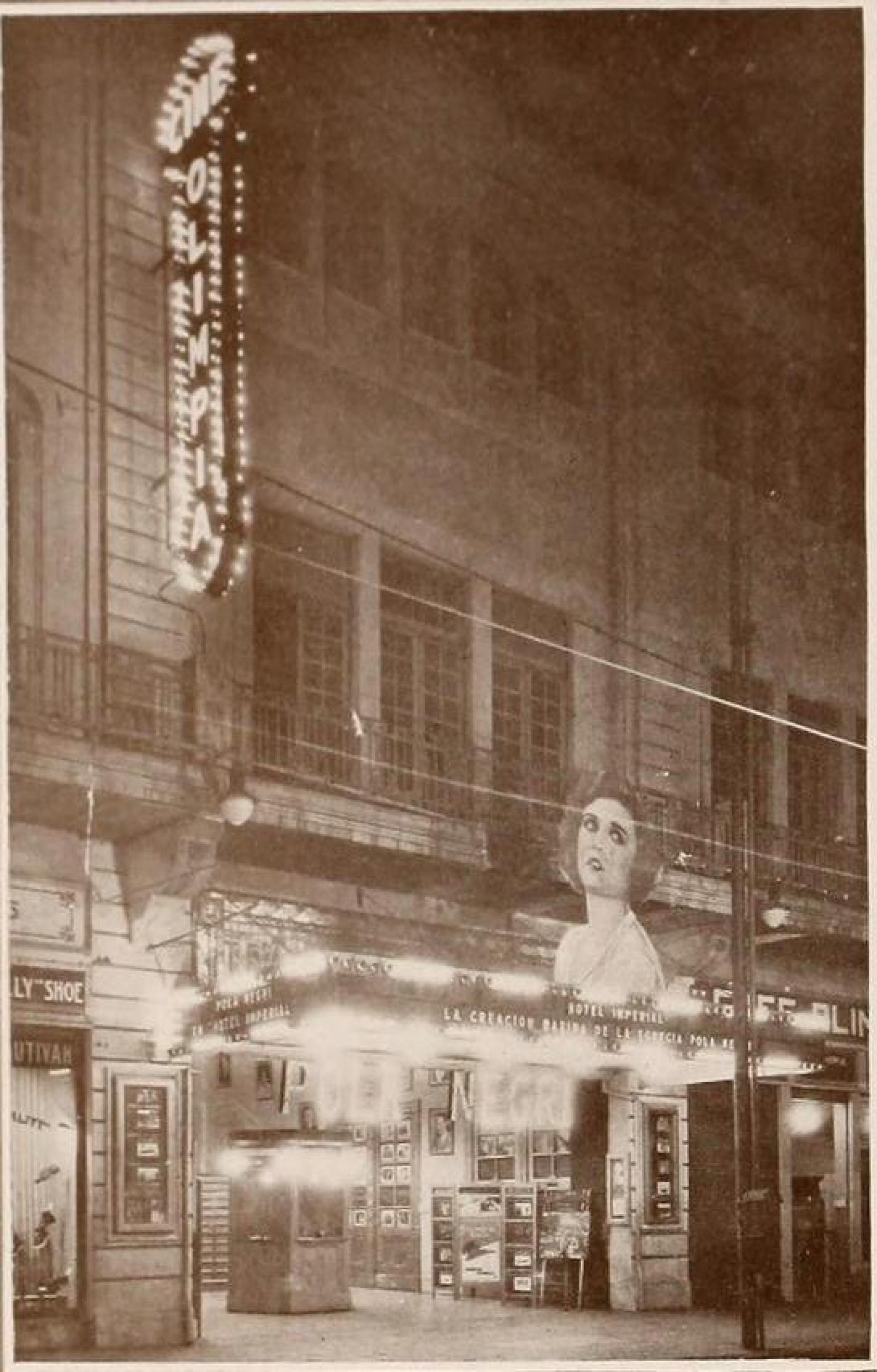

Cine Olimpia Opening Poster (1921). | Photo via Mexican Silent Cinema

For this Forgotten Masterpieces edition Tania Tovar Torres revisited the history of the fallen heroes of the grande époque of cinematographic palaces that contributed to the consolidation of the modern image of the city during the golden age of the Mexican Cinema. In a time when film theaters were buildings with grandiloquent conditions as the movies exhibited in their spaces, and the reason why their aesthetic and formal conception was intended to have palace-like features.

Cine Encanto (1937) by Francisco Serrano was lost in the earthquake of 1957. | Photo via Archivo Francisco Serrano

From the old atmospheric to environmental cinemas looking to generate from a built imaginary a particular experience, they have since included exoticisms, far away lands, esoteric worlds and references to the unknown held within their walls. Today, they have slowly turned into ruins and dust to give place to a new era, no more related to its physical architecture but to those ones on the screen, where it has set its new limits not without nostalgia.

After the Revolution (1920s)

The Mexican Revolution marked a great gap in the realization of fiction films in Mexico. At the moment, the main import of films to Mexico came from Europe; the US had not yet been fully established as a film producing center, and the tense relations between Mexico and the US, together with the stereotypical image of the Mexican bandit led to rejection, both officially as well as popular, towards many American films. France and Italy became the patterns to follow for the reopening of the Mexican Fiction cinema in 1917.

Cine Olimpia from 1927. | Photo via Mensajero Paramount

By 1920s, the frictions with the northern neighbor had softened, Hollywood began to conquer markets across the world, and the cinema became witness to a world transformation. However, The Russian as well as the Mexican revolutions, had marked the way of thought of the country. The Mexican intelectual scene was divided between revolution and socialism. This environment, wasn’t a stranger to the tendency that the Mexican cinema followed once established the basis of the national cinematographic industry, where politics and art pointed towards revolution as the main topic which the new industry followed.

Cine Olimpia (1921). | Photo via México en Fotos

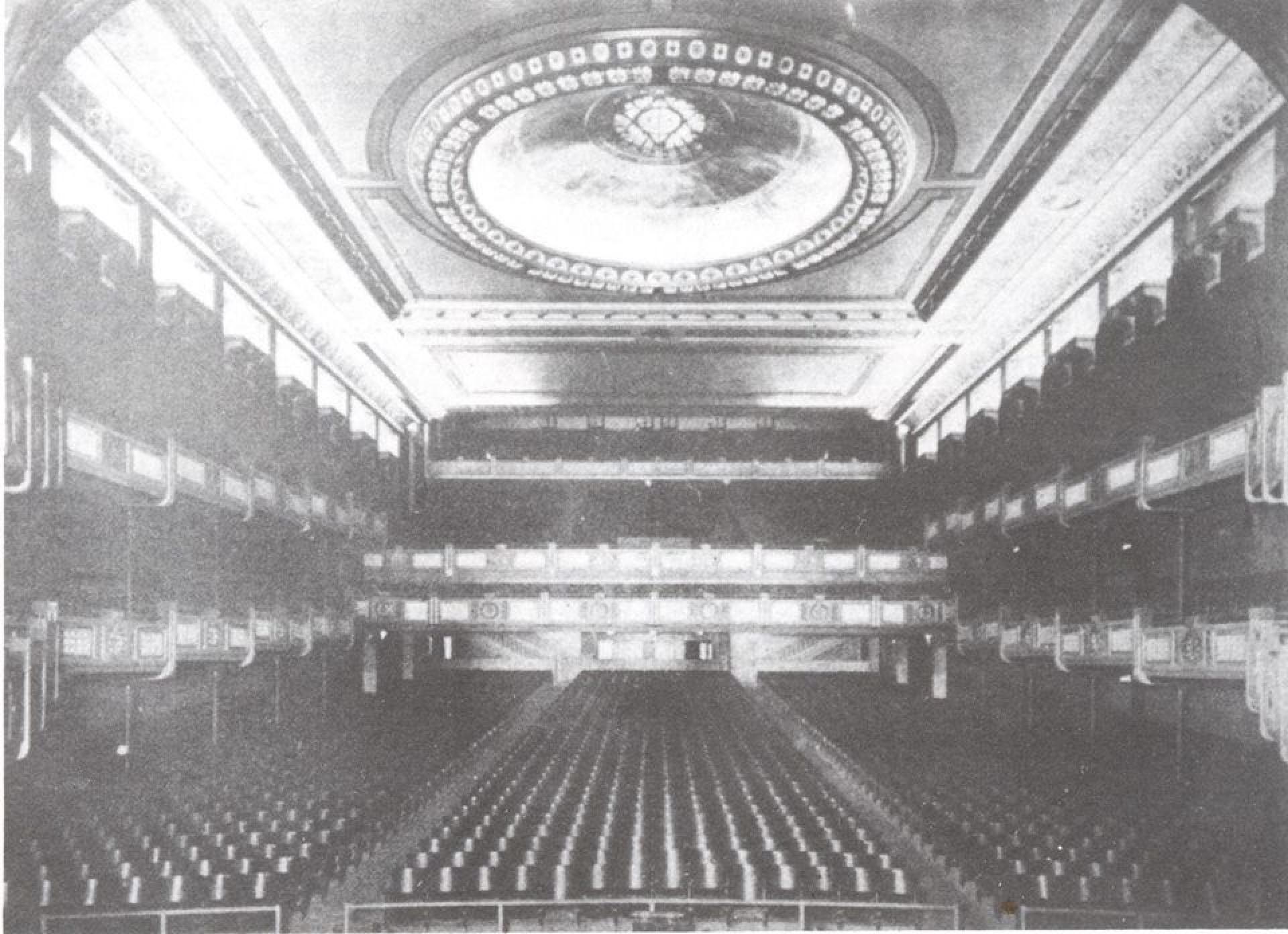

One of the first pioneer projects of what would eventually become the architectural program of the theaters-cinemas of the 1920’s was the Olimpia Cinema (whose original construction dates 1916), re-opening its doors to the public on 1921. With a capacity of 4,000 seats, it hosted two ballroom salons, a smoking room, two halls and a Wurlitzer pipe organ. Located on the City’s historical centre, it became the stage where Carlos Chávez, Agustín Lara and Manuel Esperón came to musicalize mute films. The Olimpia was one of the first theaters with sound, and projected the first ever sound film, Alan Crossland’s The Jazz Singerin 1927.

Cine Olimpia, Theater interior (1921). | Photo via Mexican Silent Cinema

After 1920, the Mexican Cinemas maintained an uneven race against the growing popularity of the Hollywood films. From the Olimpia, XEW started radio transmissions in 1930. By 1941, the theater was remodeled by Carlos Crombé, and remained like that until 1995 when its was fragmented into multiple theaters and then ended operations in 1999

Despite of sound having been incorporated into the the cinema in 1927, in Mexico it happened until 1929. A new version of Santa (1931) was the first successful Mexican film to incorporate direct optical sound, recording with a parallel sound band the images of the same film, that revolutionized the way to obtain the perfect synchrony between image and sound in the theaters.

The Golden Age (1930s)

For some historians, the true golden years of the Mexican cinema correspond with World War II; however, years before it started, the Mexican Cinema had already reached great technical and artistic level, and had a well established market. .

Cine Ópera (1947). | Photo via MXCITY Guía Insider

Cine Ópera (2015). | Photo via MXCITY Guía Insider

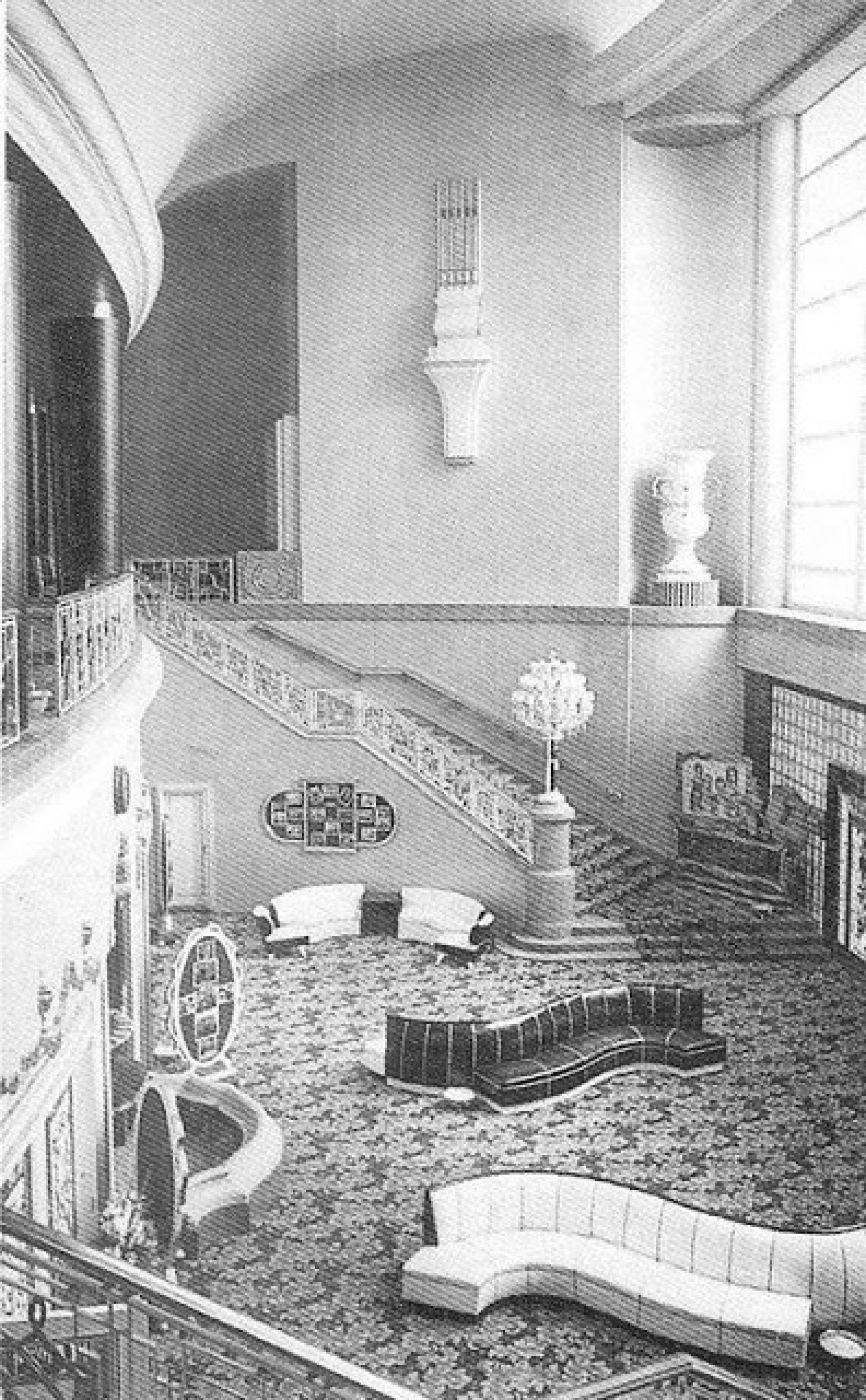

Cine Ópera, Reception Hall (1947). | Photo via Social Climber

Big North-American cinematographic studios supported altogether the development of the national cinemas for strategic reasons and to keep control over Mexicans in a time of Communist influence, which translated into a mass media strategy over the scarcely educated and easily influenced Mexican population.

Cine Ópera, Upper Level Hall (2015). | Photo via MXCITY Guía Insider

From the 20’s on until the late 60’s a generous period for the construction of this typology was held in Mexico, when a strong impulse on Cinema edification brought to life a number of the greatest theaters in town, as an answer to international events and the explosion of the Mexican Film scene. The 1930’s and 40s became the decades when the “Dream Palaces” like the Ópera, Orfeón and Palacio Chino Cinemas were built.

Cine Ópera, Theater (2015). | Photo via MXCITY Guía Insider

Commissioned to Architects Félix Nuncio and Manuel Fontanal in 1947, the Ópera Cinema was intended to reincarnate the peculiarities of Art Deco as part of the apogee of the Mexican Golden Age, involving its glory on each decorative feature -stairs, balconies, frames, doors, lamps and seats. Its facade, held then two female statues wearing the tragedy and comedy masks, where Mexico City was the exquisite repertoire of details and histories. From its opening on 1949 the Ópera Cinema became one of the most populars in the Mexican capital for decades.

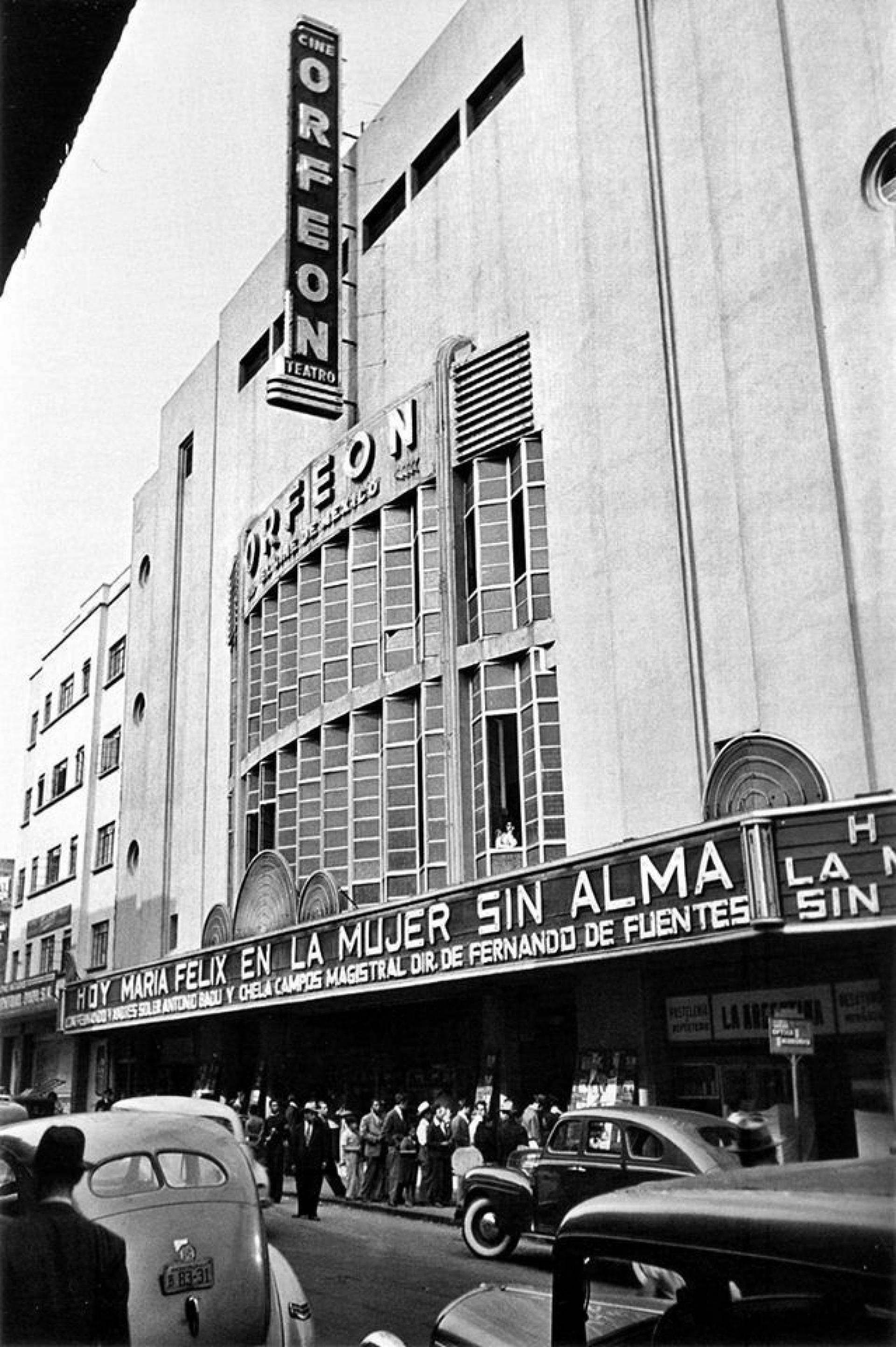

Cine Orfeón (1938). | Photo by Juan Guzmán, FotográficaMX

For 44 years, it operated as a cinema and theater until it started its decline after the cracking of one of its screens during the 1985 earthquake. After that, the Ópera Cinema remained very quiet until 1993 when its was taken again as a concert hall, however, due to an altercate with the British band Bauhaus, the place closed for good on October 12, 1998.

Cine Orfeón (2016). | Photo by Karina Áviles, El Exclesior

A similar fate is shared by other cinemas like the Orfeón, the colossal theater hosting up to 4628 seats. Originally built in 1938, it re-opened in 1948 after a remodeling into Art Deco style under American architects John y Drew Eberson, the Orfeón was part of the renowned premier theaters, together with the Alameda (destroyed during the ’85 earthquake) the Metropólitan and the Palacio Chino. Remembered for being one of the largest and the long queue lines to get in, the theater of this cinema was constituted by the lunette, the box, and a gallery that allowed to receive up to 6000 visitors. Today, these three cinemas are occasionally used as event theaters.

Cine Palacio Chino (1940). | Photo via La Ciudad en el Tiempo

Cine Palacio Chino (2018). | Photo via Dulce Ahumada, Más por Más

Cinematic Urban Sprawl (1940s)

The boom of the Mexican Cinema favored the uprising and consolidation of an authentic frame of national stars that would become the main figures in a precedent-less star system in the history of the cinema in Spanish. During those years, the Mexican Cinema explored more themes and genres than ever before, especially the “ranchera” comedy genre, cultivated in Mexico without paragon in the rest of the world due to its Mexican culture and idiosyncrasy.

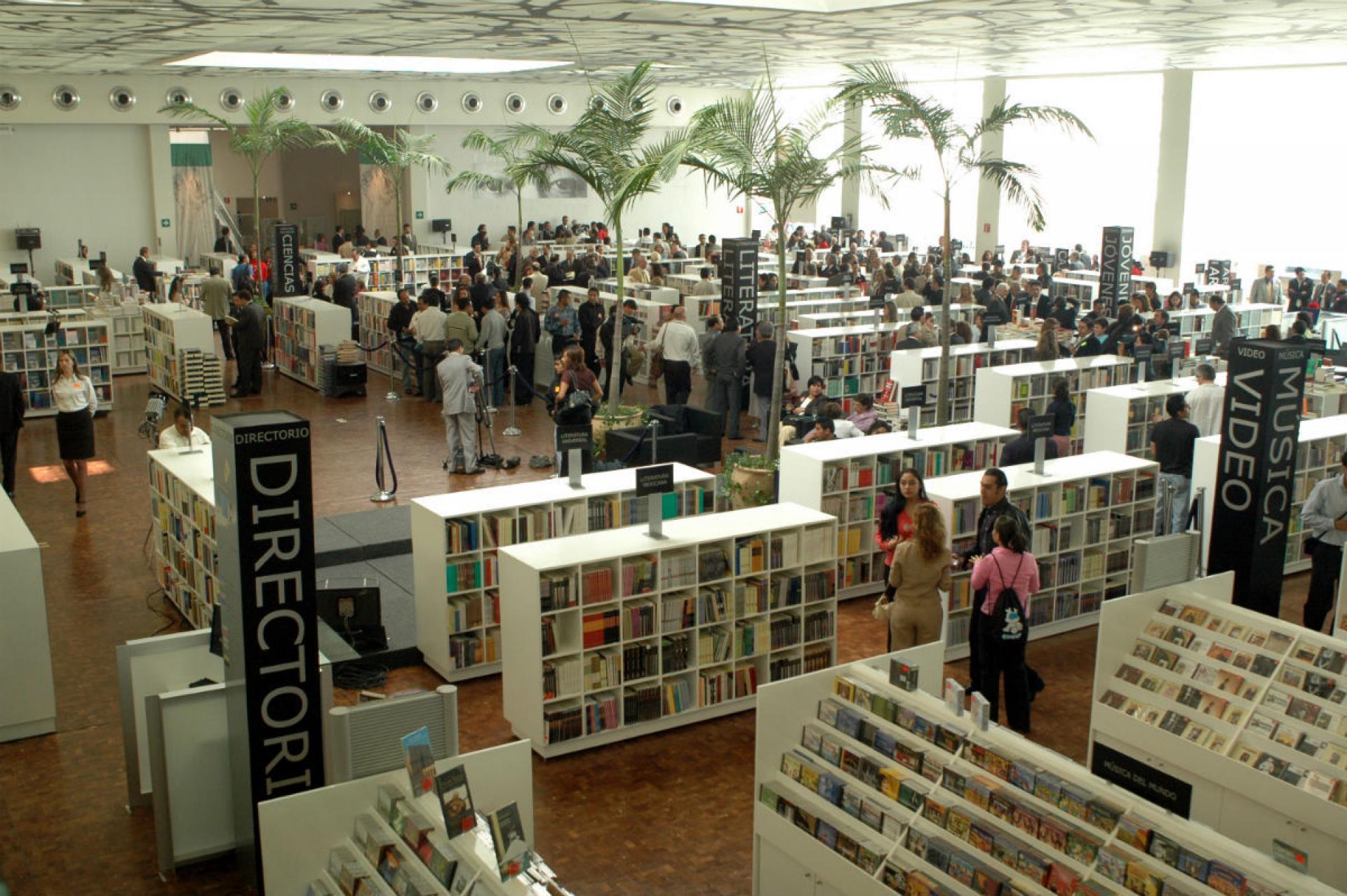

Centro Cultural Bella Época (2018). | Photo by Ligia Bang, Revista Fernanda

Centro Cultural Bella Época, interior (2017). | Photo by Christian Gama, Progreso

Its internationalization came with the film ¡Ay Jalisco, no te rajes! (1941) interpreted by Jorge Negrete, and its ulterior ending came with the demise of the popular actor and singer, Pedro Infante in 1957.

Cine París (1954). Juan Sordo Madaleno and Jaimes Ortiz Monasterio | Photo via Una Vida Moderna

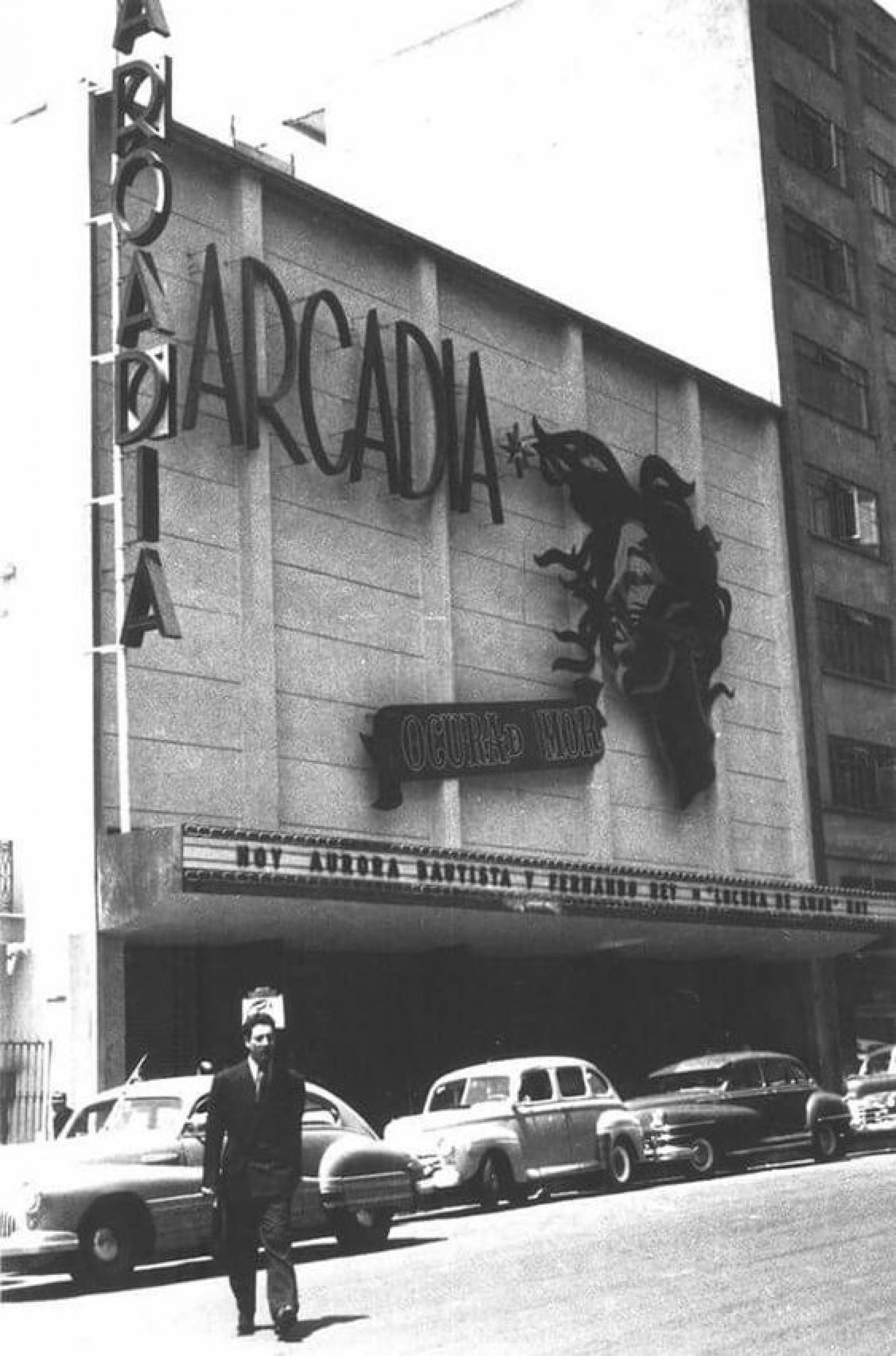

Cine Arcadia (1936). Turned into a Parking Lot. | Photo Unknown source

Literary pieces, comedies, police movies, musicals and melodramas formed part of the Mexican cinematographic inventory of those years. Also, by the end of this period a new genre would be instated that as the rancheras comedies, had no rivals outside Mexico: the “Luchas” genre or Lucha Libre films. Because of this, the construction boom of elegant and palace-like cinemas proliferated particularly in the city center, but they slowly extended to the surroundings, a phenomenon linked to the urbanization of the neighborhoods of the time.

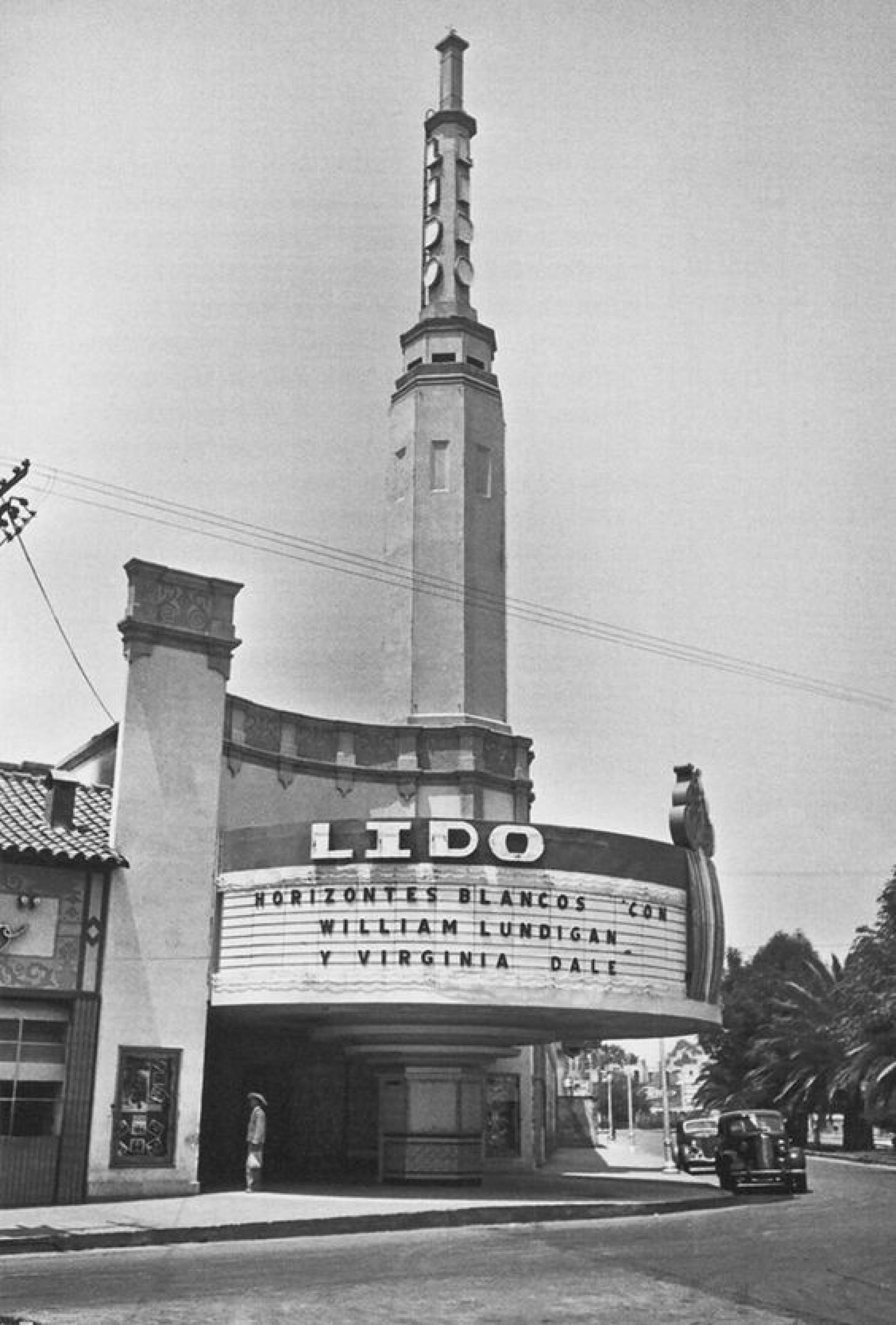

Cine Lido (1942). | Photo by Juan Guzmán, FotográficaMX

Located today in the Hipódromo CondesaNeighborhood, the Lido Cinema was the first movie theater located outside the city center. Designed by Charles S. Lee, its was based on Art Deco style and designed to host approximately 1310 viewers. The architectural trends at the time gave to the building influences of the Californian Colonial and Spanish Revival styles, taking old ancient Spanish and Mudejar elements, where its most important compositional elementwas a 20 meters tall tower located in the entrance, framed by the marquee.

Cine Lido, Theater (1942). | Photo via Sinapsis MX

The Lido opened in 1942 and ran three decades of famous reputation. However, in 1978 its decadence started due to an increment in admission prices and to the establishment of newer cinemas with more attractive facilities from comercial chains. Despite an attempt of remodeling and re-opening under the name Bella Epoca Cinema in 1980, the prices and competitions couldn’t be stopped and by 1999 the Mexico City Government acquired the estate that was later sold to the Economical Culture Endowment, and with the support of the neighbors that sought the protection of the building as a cultural space, Mexican architect Teodoro González de León was commissioned to remodel the space, today the building stands as the Bella Epoca Cultural Centre.

Cine Lindavista (1942). | Photo via La Ciudad en el Tiempo

Cine Lindavista (1942). | Photo via La Ciudad en el Tiempo

Cine Lindavista (1942). | Photo by William Gabel, Cinemas Treasures

The Lindavista Cinema opened too on 1942. Built in a traditional monastery scheme, this cinematographic monument in the north of the city took advantage of its location in a corner, with a tall tower that stood up as a urban beacon above a roundabout and marquee where the ticket booth was held and the complex integrated the enormous entrance door to an open space. The architectural proposal of the Lindavista cinema was of simple characteristics in its composition and saturated in neocolonial details that made for a resemblance to the old catholic temples of the viceroyalty. The entrance to the theater was defined by a large arch and two dome volumes that conformed the facade. In the 1970s, the building suffered a great change as it became a children cinema, for which its interior decorations were traded for animal kingdom cartoons, and the tower was painted to resemble the Disney World castles. The cinema was closed and short after, abandoned. In time, the building underwent a slow transformation on an incomplete process to become the San Juan Diego Sanctuary.

Cine Lindavista - Sa (2017). | Photo by Archive Fhasaov

The Mexican cinematography also tried to develop and consolidate a realistic tradition. Marked by the time where diverse realisms reached its classic dimension, the work of Alejandro Galindo - framed between 1938 and 1953 - is one of most significant of the Mexican Social Cinema. The intentions of the Mexican realistic cinema reached a new dimension in Campeón sin Corona (1945) directed by Galindo. The movie offered a detailed psycho-sociological study of the historical, racial and cultural conditions that, according to a certain perspective of the time, determined the Mexican lower class. The genre showed the life of the neighborhood of the city, reflecting the growing urbanization phenomenon of the country.

Cine Lindavista (2017). | Photo via Dulce Ahumada, Más por Más

Next to the big theaters, smaller neighborhood cinemas also known as “de piojito”(cuddling places) were built and survived with the second run programming, but eventually turned into spaces of coexistence for a social sector that was growing, where the city and the cinemas, managed to develop a close and daily relation with their environment while leaving a mark in their audiences. Going to the movies during this time, was a unique sensorial experience. It was a motive for families to move to the cinemas; seeing the announcement of the film with the light bulbs on at the entrance marquee showing what was projected, preparing its audience to an immersive experience; go the the candy-shop during the film break and comment among them the movie.

Modern Decline (1950s)

By the 1950’s, the projection theaters proliferated but in functionalist and modern buildings, like the Roble, Continental and Las Americas Cinemas. The Theater El Roble opened in 1950, and was one of the most spectacular and elegant cinemas that the city had.

Cine El Roble (1950). | Photo via Colección Carlos Villasana, Más por Más

The theater with three gallery floors, was one of a kind in Mexico. It was the venue where all the luxurious international movie premiers and cultural events of the 60’s and 70’s were held. Its neoclassical interiors with its yessum sculptures, beveled glass niches for its water fountains and smoking salons, however, suffered severe damage during an earthquake in 1979. A slow agony that ended fifteen years after when its was demolished.

Cine Las Americas. José Villagrán García. Movie Theater lost in the earthquake of 1957. | Photo via Colección Carlos Villasana, Más por Más

The first transmission of the Mexican Television initiated in 1950. Soon after, the television reached an enormous penetration power into the audience. Television antennas became something common in the the Mexican household, an while the first image of the television in black and white appeared in a small oval screen very much imperfect and lacked the resolution of the cinematographic image; the television represented the competition of the new medium, influencing decisively cinematic history, forcing it to look for new outcomes technically, but also thematically and genre-wise. Wider screens, 3D cinemas and an improvement in color and stereophonic sound, were some of the innovations of the North-American cinema in the early 50’s. The elevated cost of the technology made it hard for Mexico to produce films with the same characteristics. With an antiquated infrastructure, little money, a more demanding public, and a saturated market of North-American productions, the Mexican Cinemas faced its own dawn.

Cine Continental (1958). | Photo via Algarábia

The cinemas became a unique spectacle accessible to all audiences. Among all the memories, there were still those of the cinemas distinguished for their thematic. In 1958, the Continental cinema was opened with a capacity of 2350 seats that operated as an exhibition theater for national and international films for 15 years, before closing doors to be remodeled and become La Casa de Disney (The house of Disney) on 1974.

Cine Continental / La Casa de Disney (1980). | Photo via La Ciudad de México en el Tiempo

The theater had the peculiarity of having restrooms designed for its young audience, but more important was its facade that had been transformed to look like the Disneyland trademark Castle. Even though the Continental preserved its original program for many years, the building didn’t escape the transformation at the end of the XX century. In 1998, its main projection salon was divided into eight theaters equipped with dolby sound system and reclining seats, becoming the Multimax Continental Cinema. The Continental is considered the only children’s cinema to ever exist in Mexico of those dimensions before closing its doors for good in 2008, waiting as a graffitied and deteriorated estate to become a self-service store.

Cine Continental (2014). | Photo by Carmen García Bermejo, El Financiero

By the end of the 50’s the Mexican cinema was experiencing an almost complete inertia. The traditional formulas had exhausted its entertaining capacity and had began to repeat the films with other actors but with the same themes to an everyday more indifferent audience. By the end of the decade, the Mexican Cinema crisis was not only advertible to those who knew its economical problems: the same tired, routinely and vulgar tone, and a lack of inventiveness and imagination only evidenced the end of an era. The censorship removal in the U.S. allowed for more bold and realistic themes: France had a young generation of filmmakers educated in the the cinematographic critiquethat started a new movement; in Italy, neorealism had affirmed the career of new directors. In the meanwhile, the Mexican Cinema struggled with bureaucratic and union problems. The production was concentrated on a few hands and the possibility of new filmmakers to emerge was almost impossible. By making the cinema an affair of national interest of the Mexican government, they were digging the industry’s own grave.

From castles to multi-cinemas (1970s)

Upon the 1970s, the government used the cinema, radio and television as a formal means of national and international communication for the first time in political history. The cinemas experienced a virtual nationalization; something particular for a non-socialist country. But among the changes, the Cinematographic National Bank received a thousand million pesos investment to modernize the technical and administrative apparatus of the national infrastructure. It was precisely during the 70’s when the small and majestic theaters began to be fragmented and displaced by the multi-cinemas predecessors to the multiplex model.

Multicinemas La Raza (1970). | Photo via Cazadores de Mentes

These were spaces designed with three or more theaters equipped with more modern technology. Among them, there were La Raza, Universidad and Satélite Multi-cinemas located in the outskirts of the city. The 70’s started a process of new exhibition models and new types of facilities; smaller and well distributed in different points of the city; the larger cinemas were fragmented and changed programing, while others disappeared.

Multicinemas Universidad (1969). | Photo via Archivo Sordo Madaleno Arquitectos

The technological exhibition development, the crisis of the Mexican theaters, the exhaustment of the exhibitions model in Mexico, as well as the 1985 earthquake that destroyed many of those old big theaters, affected the urban surroundings where they were located turning them unsafe, dirty and therefore driving people away. The 90’s disappeared the last Theaters Operated by governmental organisms that subsidized the exhibition and distribution of Mexican cinema in the country, and the so called New Mexican Cinema underpinned the “quality cinema”.

Multicinemas Satélite Information Napkin (1914). | Photo via Los Satelúcos

In the coming years, the Mexican cinema slowly recovered. However, the cinematographic palaces built to host it, proved to be obsolete and were almost forgotten. Today the Mexican film industry shall live in the thousands of movie theaters of multiplex Mexican empires Cinemex and Cinepolis around the world, and in the memories behind each demolition of those old temples that gave them sustenance.

Tania Tovar is an architect, writer and curator with an interest for narratives where architecture stands as main character. She graduated from the National Autonomous University of Mexico; studied at the Stuttgart State Academy of Fine Arts in Germany; and holds a Masters in Critical, Curatorial and Conceptual Practices in Architecture from the Columbia Graduate School of Architecture, Planning and Preservation in New York. She is founder of Proyector, a curatorial platform an exhibition space based in Mexico City. She is a Consultant for the German Cooperation Agency for Sustainable Development in Mexico; and has previously worked at the Canadian Centre for Architecture in Montreal, the Arthur Ross Architecture Gallery in New York, the Museum of Science and Art and the National Council for Educational Development in Mexico City.