FOMA 1: Five Projects. One Half Century. One Whole Nation.

Forgotten Masterpieces is a new serial which explores forgotten buildings curated by architects, researches and photographers. We are starting Forgotten Masterpieces with Alessio Rosati from MAXXI Rome. As curator of this first FOMA he selected five moments which are presenting half of the century of forgotten architecture in Italy.

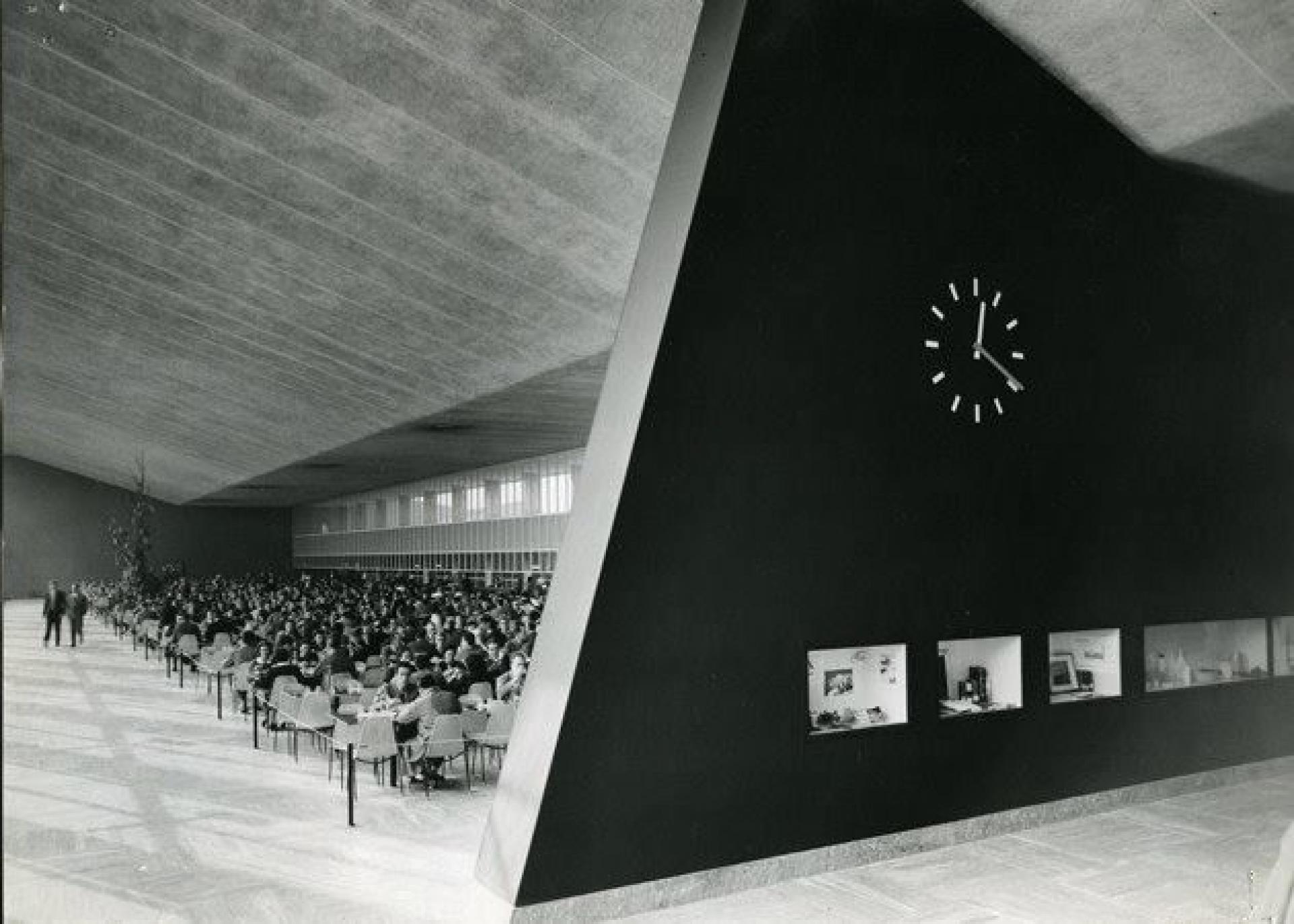

Workers Canteen for 1600 employees of Pirelli. | Photo © Archive Pirelli

In Italy, there is a vast amount of unknown architecture. Amazingly, there has been little published or celebrated about these projects – ones that perfectly represent this nation, its political and economic culture, as well as the human and environmental landscape. The five presented here are not just buildings, but chapters of a paradigmatic story spanning half a century. From north to south, these projects have beard witness to the transformation of territories, customs and a profession. At this time, architecture and its practitioners, grew less and less defined or definable, in a country characterized by a controversial relationship with its own history and modernity.

At the end of World War II Italy was a nation brought to its knees with a single priority: housing for its millions of displaced citizens. After years of Fascism, politics has lost interest in architecture, too polarized by between the phenomenological-realist approach of Ernesto Nathan Rogers and the organic-idealistic one of Bruno Zevi. The reconstruction at hand is eminently a practical matter, to be addressed by resorting to local labor, materials and techniques—a mandate seemingly recalling Mussolini’s autarchy. Although at the time urban planning is a topic of great interest internationally, in Italy, planning and development is largely delegated to the initiative of private companies. This is especially true in the northern region, as it is home to the large industries.

The self-service system is adopted for the first time in Italy in the Pirelli’s Workers Canteen. | Photo via Archive Pirelli

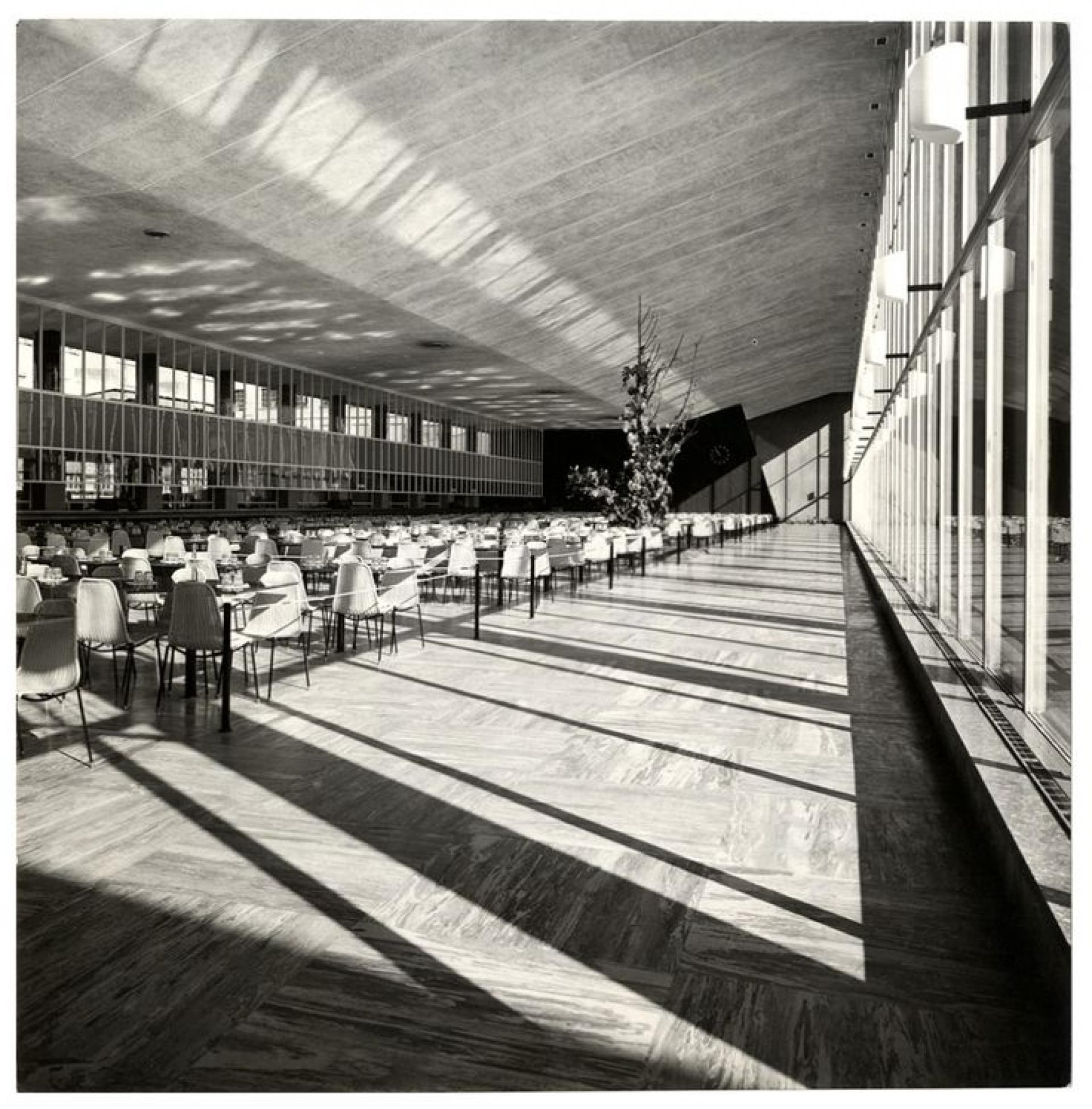

In the early 1900s, Bicocca, a suburb of Milan, develops around the Pirelli factories. In 1955 this industrialization has grown to a massive scale and the tyre manufacturing company appoints architect Giulio Minoletti to design a canteen for its 1600 employees. Following a study tour in the United States organized by the client to study similar buildings in North America, the project is tackled with two priorities: distribution and use. The diners are subdivided into two separate shifts of 800 each for expediency; the self-service system is adopted for the first time in Italy. Food preparation, cooking, distribution and consumption are organized along four parallel lines; the routes of kitchen staff and diners are carefully considered to avoid any possible interference. To abandon the factory environment during the meal, Minoletti designs the remaining area as a perspectival setting. Through the use of earthworks, he molds a grassy slope and places a shallow water basin at its foot. It is this picturesque landscape that the dining room overlooks through a large curtain wall, one that in the summertime is operable, to stretch the interplay between interior and exterior. The public and critics alike warmly welcome the Pirelli canteen. Yet sadly, both the relocation of the company and the urban transformation of the area brought about the demolition of the building in the late ‘90s.

The building with a view. | Photo via Archive Pirelli

Also in 1955, the International Olympic Committee selects Rome as the seat of the XVII Olympiad. It is an important opportunity for Italy and one of redemption for the Capital. For the games it becomes clear that the city lacks the adequate infrastructure to host the event but the nation’s building technology lags behind. Therefore, the government directly commissions the design and construction of sports facilities to established designers and construction firms.

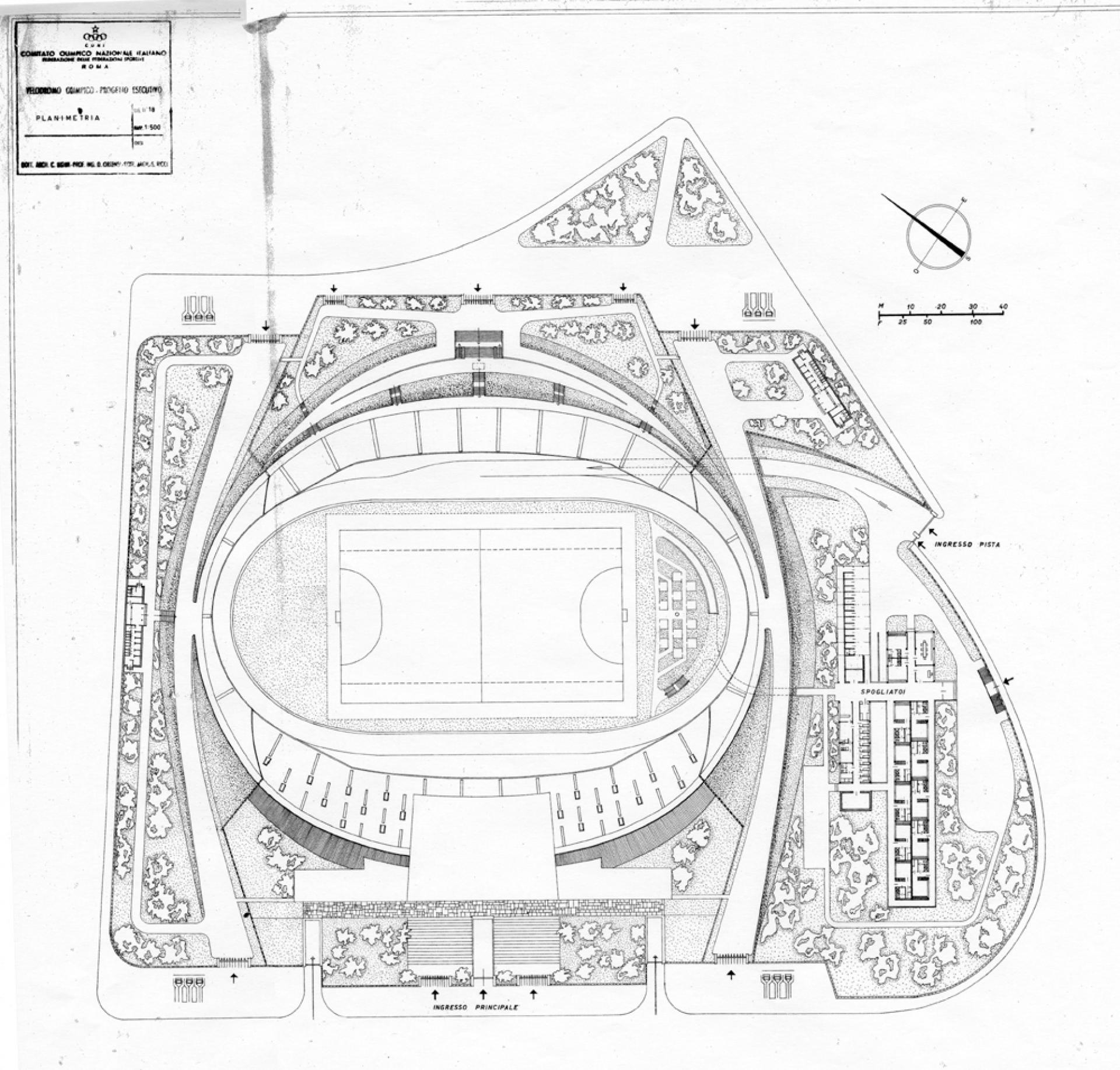

The only exception is the competition for the Olympic Velodrome, to be built in the suburban EUR district. It is a particularly complex project, for which there very little direction given; the competition brief only provides specifications concerning the flexibility of the facility, visibility and the connection to the external thoroughfare in order to facilitate direct access to the participants in possible cycling races. The only physical constraint manifests as a material specification for the track, which is to be built in wood. Among the 30 entries, the jury selects the one of the Roman architect Cesare Ligini. Built between 1957 and 1959, the Velodrome is designed to offer visual comfort and access to the 18,000 seats. The facility works beautifully. However after the Olympics, the last public event held there is the 1968 World Cycling Championship, after which any maintenance ceases and forty years of neglect bring about the demolition of the complex in 2008.

The last public event in Olympic Velodrome was the 1968 World Cycling Championship; the complex was demolished in 2008. | Photo via CONI Archive

The year 1960 corresponds to the economic boom and the Dolce Vita, a lifestyle marketed heavily to influence a luxurious lifestyle with fast sport cars and Italians dream of being able to do the same. Inspiring many to abandon their Vespas for automobiles to embark Sunday road trips or cross-country summer tours. The national economic development then grows based on roads and private means of transport but the topography of the long and narrow peninsula complicates railway connections, and the presence of the behemoth manufacturer FIAT make the open road the place where most design innovation lies. This new era reshapes the landscape of Italy, and brings about the need for filling stations and restaurants along the motorway. Thus, the Autogrill is born. These bridging structures are constructed along the northern motorways housing restaurants and cafes, and inviting motorists to bookmark their journeys with various stops. The first Autogrill of this type is so successful that, in 1960, it is published in Life magazine as an expression of the renewed identity of Italian luxury.

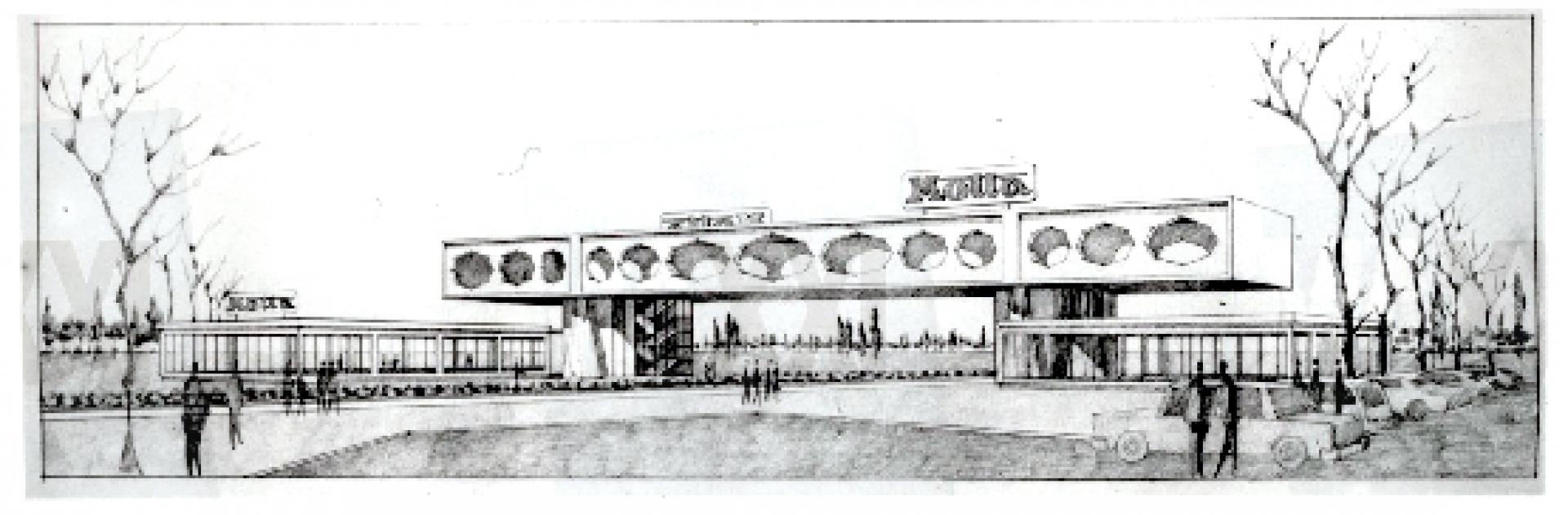

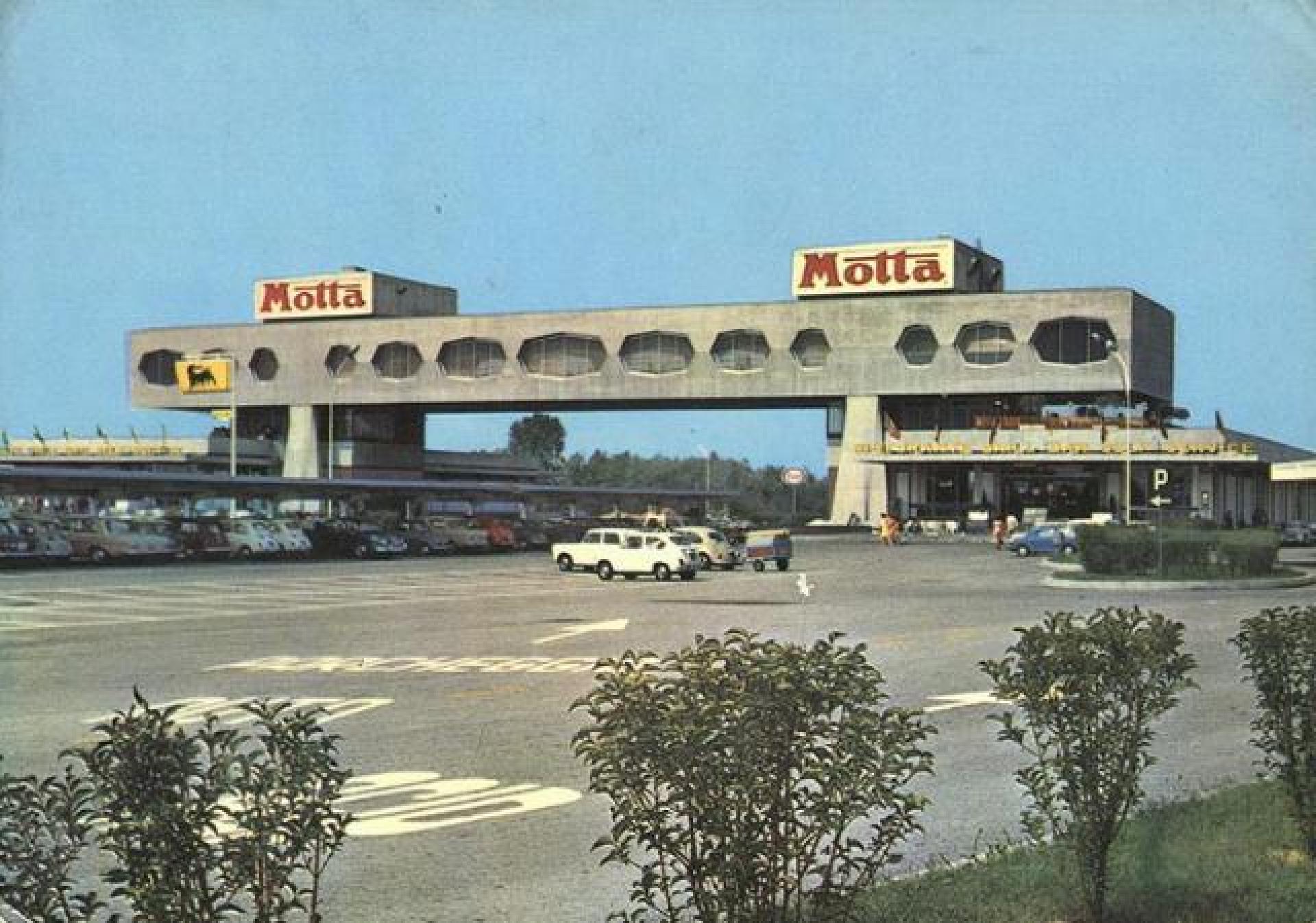

The design and construction of particularly notable Autogrill is carried out between 1961 and 1966 in the northeastern town of Limena, near Padua. It is designed by the Bolognese architect Melchiorre Bega in collaboration with Pier Luigi Nervi, an internationally recognized engineer and builder. The building consists of two large rooms on the ground floor, one for each direction, where there are bars and cafeterias surmounted by the bridge structure of the restaurant, with its 40 meters span, crossing the six lanes of the Milan-Venice motorway.

The structure is made entirely of cast-in-place reinforced concrete, with four variable-shaped pillars onto which rest the beams supporting the ceiling of the restaurant. | Photo © Archivio storico ENI

The Autogrill is a true icon of the economic rebirth of Italy Its modernity and elegance as a destination along the journey lends itself as both visually pleasant and also a representation of speed and growth of the nation of Italy. They became the manifestation of new ideas idea driving the nascent national progress.

Windows are opened through natural voids where the structural holes of the beams are. | Photo © Alessio Rosati

This short-lived sense of progress and growth gives way to the turmoil of the '70s. A decade shaken by social tensions marked the beginning of a particularly difficult period for architecture; deprived of any public authority, the most important designers retreat, writing and theorizing whilst building very little, a prelude to the crisis sanctioned in the following decade by Manfredo Tafuri in his History of Italian Architecture (1944-1985).

The 1980’s bring about both a period of opulence and laxity of local Italian design. The following decade sees a cure for this malaise. The country is revived through a renewed interest for the art of building regarded once again as decisive in the urban transformation for social interests. Thus begins a new era of national and international design competitions, forcing Italian professionals to test their skills and construction firms to enhance the quality of their work.

Contrast of the architecture offers a view to the natural landscape of the park. | Photo © Roberto Pirzio-Biroli

During this period of renewed optimism, the Cormor Park in the northeastern city of Udine is completed. Previously the park had been reduced to an illegal dumping site, but its recovery was led by the Friuli architect Roberto Pirzio-Biroli. Through the study of historical maps and original documents, the architect identifies the remaining natural traces of this urban periphery and reinterprets them with sensitivity, restoring the landscape through soil conservation and reforestation. Shaping the terrain, Pirzio-Biroli creates embankments and lookouts, cliffs and woods, roads and pedestrian paths. Inspired by the work of Heinrich Tessenow, the architect marks the entrance to the park with a pavilion to accommodate small events and the caretaker’s house. The design contrasts a forest of slender steel columns topped by a light cover against the verticality of the poplar grove beyond. The resulting space is a contrast through which to view the landscape. It is a project met with international acclaim for its both environmental as much as economic approach, and is praised for its attention to the visitor’s experience.

Sequences of the Cormor park building. | Photo © Roberto Pirzio-Biroli

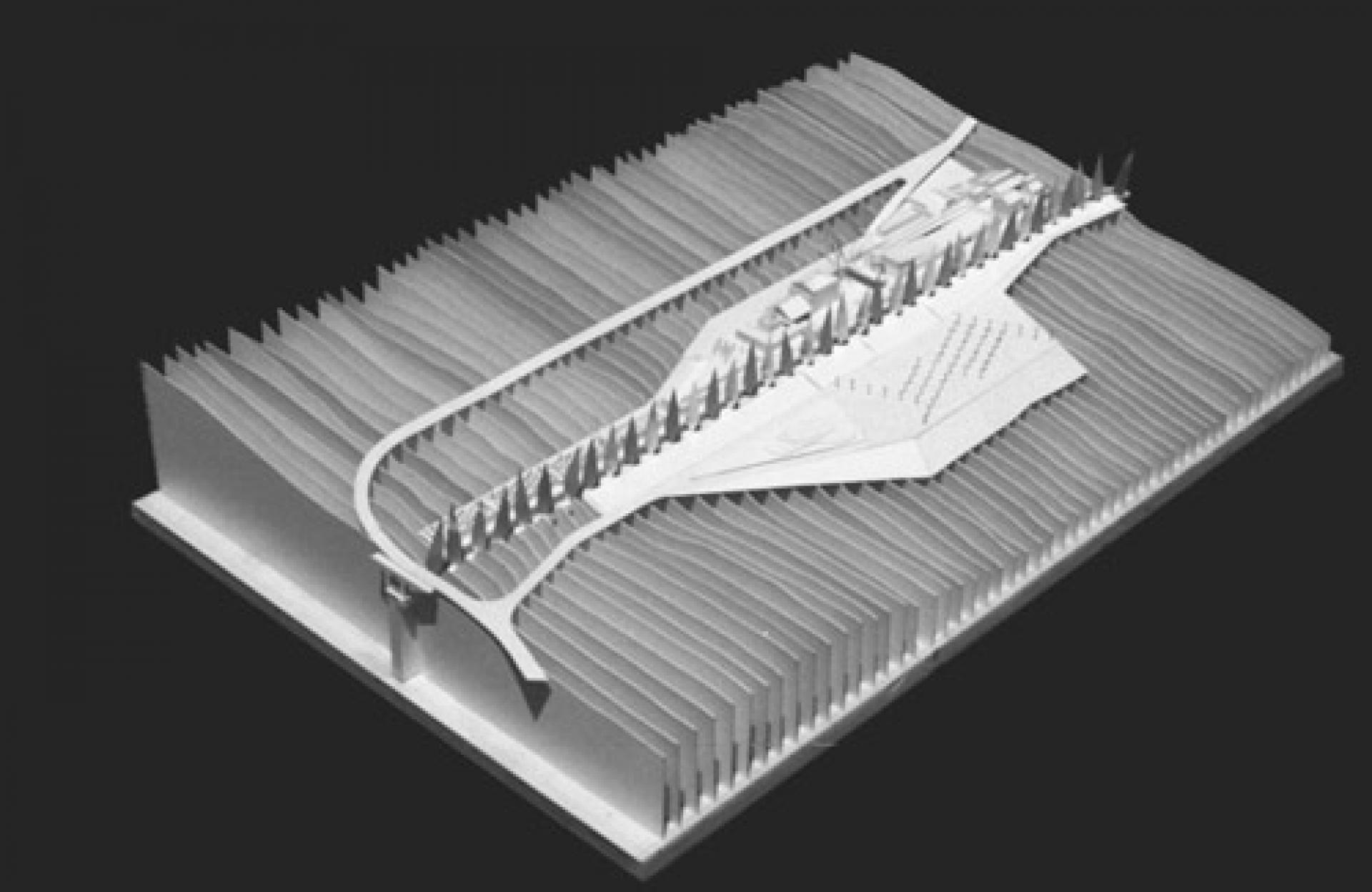

The same happens in 1999 in the heart of Sicily where, between Caltagirone and San Michele di Ganzaria, a 35 kilometer stretch of an old decommissioned railway is redesigned into linear cycle park. Thus turning the ruin into a light infrastructure for leisure, tourism and the new organic agriculture. The design of Linear Park is by Marco Navarra, an architect native to the area who, in addition to studying abroad regularly participates in international design competitions and engages with the international design community. His project utilizes the historical evidence left by a local railway interwoven with ancient landscapes including a prehistoric necropolis, 18th-century farmhouses and a Roman villa. These become episodes of the cycle route. Trees, plants, slender metal structures and colored flooring to compose a simple and sensitive narrative, previous structures to turn them into venues for events, shops, food stands and bicycle shelters. In 2003, the linear park receives Gold Medal for Italian Architecture for the debut and is also nominated for the Mies van der Rohe Award. Ultimately, the project has fallen victim to neglect and vandalism, and these color the current state of the park.

Marco Navarra turned the ruin into a light infrastructure for leisure, tourism and the new organic agriculture but the project has fallen victim to neglect and vandalism | Photos © Salvatore Gozzo

This is a story that has no happy ending or any true conclusion. Today, Italy is experiencing yet another and arguably much deeper crisis of economy, but also one of identity and culture. While the future is uncertain, and much of the past is a lesson that is too often ignored, this story does show that, despite everything, even as an episodic influence, architecture plays a role in contributing to the quality of life of a nation and its people.

Alessio Rosati (1971) was born in Rome where he studied architecture, and is currently working for MAXXI, The National Museum of XXIst Century Arts as well on FOOTNOTES a series of short stories on architecture to be published in 2017 by divisare.