Pioneer Architects XI

Architecture has been traditionally a man’s world. Despite women’s increasing recognition in this field, the discourse on gender and architecture has been exclusively confined to women practicing in the West, leaving in anonymity a large number of female professionals who have made important contributions to the profession.

Rendering Fay Kellogg Pearson’s Magazine February 1911. | Photo via Preservation in Mississippi

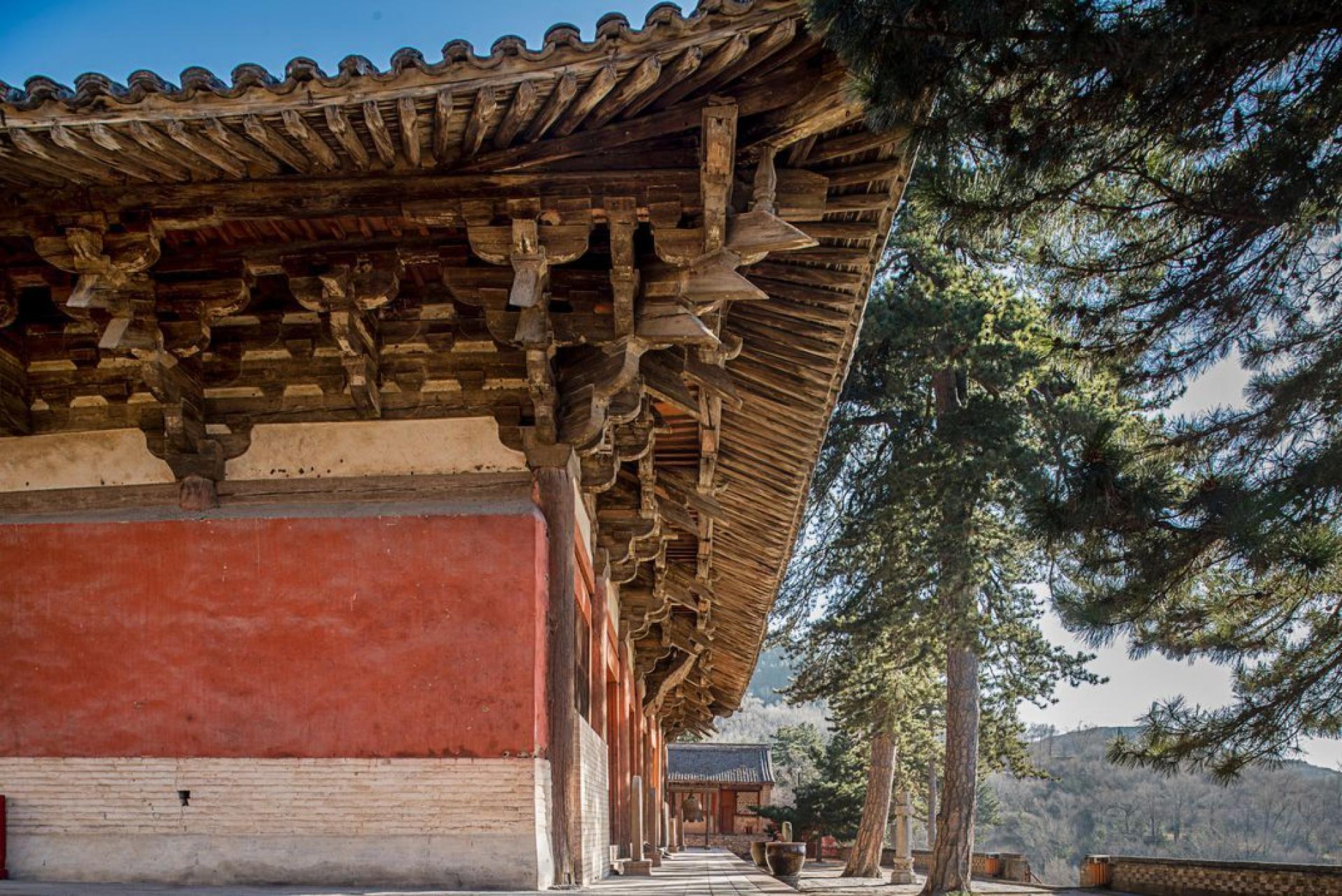

The style of the roof used for the Foguang was to Lin Huiyin known only from paintings and literary descriptions. | Photo by Stefen Chow

For the XI issue we shift the focus away from the more familiar Western contexts. We introduce the work of pioneer architects from Latin America, Asia and the Middle East who celebrate the rich cultural heritage of their homelands and have promoted initiatives for the conservation of their built environment. While non-Western women architects often imported international styles that broke with local traditions - such as modernism - these pioneer designers focus on an architecture that acknowledges their own culture, prioritising restorative interventions and the modern adaptation of traditional crafts over standalone iconic structures

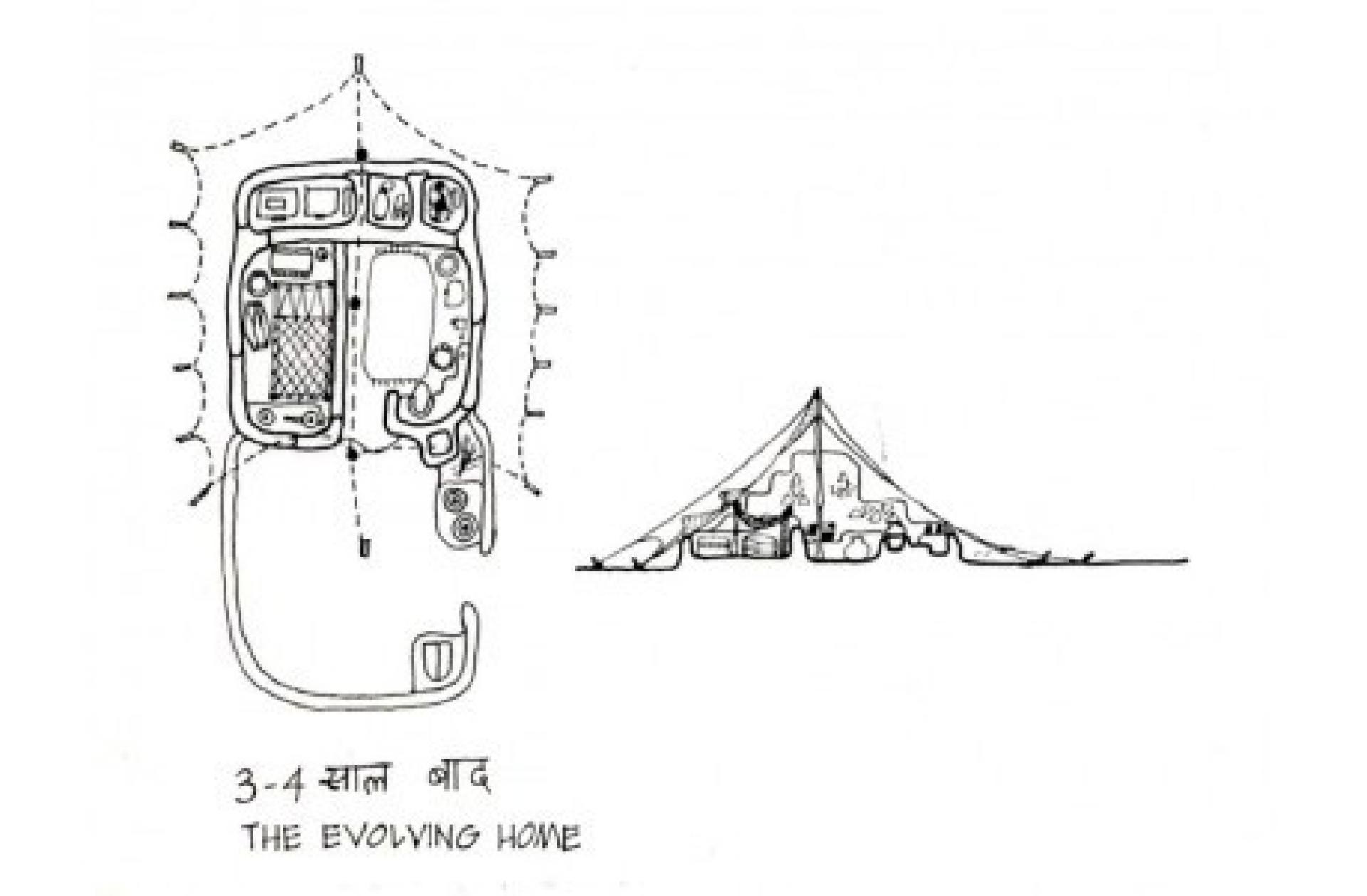

Drawing for the Anandgram by Revathi Kamath. | Photo via Architects web

The value of their work lies in the strong social and ecological tones that come with every project, reflecting a practice that encourages the preservation of both physical and sociocultural contexts. These practitioners are not strictly confined to architecture itself but often operate across different fields of expertise and offer a multidisciplinary approach to understanding places. From political activists and strong advocates of social change to writers and engaged academic researchers, they take on multiple roles. While these architects’ work may not seem pioneering at first - since the conservation of historic buildings has long been practiced in the West - their contribution to architecture and their legacy should be understood in relation to their local contexts, where demolition has often been preferred - or imposed - over preservation.

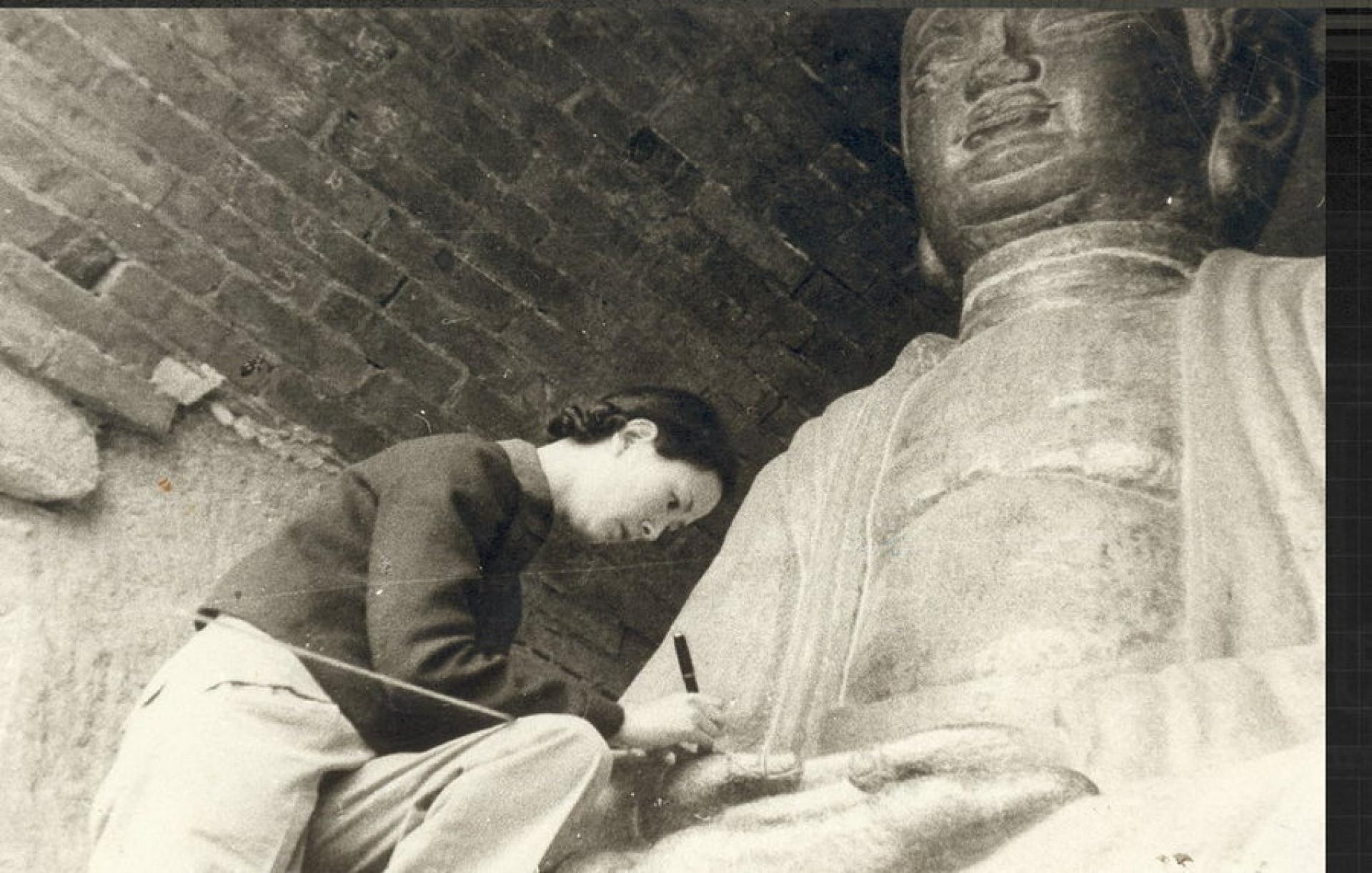

Lin Huiyin was barely acknowledged during her lifetime due to her gender. | Photo via Women of China.

Lin Huiyin (1904-1955) was a Chinese poet and considered the first woman in modern China to become an architect. Her studies and travels during her youth have influenced her interests for historic architecture and conservation. With her husband Liang Sicheng were the first architects to have adopted a preservationist role for China’s built heritage. In the 1930s, they started documenting traditional Chinese buildings found during their remote travels in rural areas of the country. This new attitude towards historic structures was of particular importance in China as they were not given the same value as in Western countries, where ancient buildings were object of study and preservation. Although Lin’s was barely acknowledged during her lifetime due to her gender, she has increasingly gained recognition for her contribution on traditional architectural knowledge.

Cahide Tamer was one of the first architects in undertaking extensive restoration works in Turkey. | Photo via Istanbul Kadin Muzesi

Cahide Tamer (Istanbul, 1915-2005) was a pioneer in the field of restoration in modern Turkey and one of the first women architects in the country, graduating in architecture from the Academy of Fine Arts in Istanbul in 1943. She has been involved in restoration projects of historic monuments from the early stages of her professional career, initially working for the Department of Museums and Antiquities until 1956 and later for the Bureau for the Preservation of Ancient Monuments. Throughout her career, Cahide consolidated her role as a heritage architect and conservationist by taking part in over a hundred restoration projects.

Restoration of Rumeli fortresess in 1959. | Photo via Un día una arquitecta

Suad Amiry established the first programme for preserving the built heritage of Palestinian villages. | Photo via Built Palestine

Suad Amiry (Damascus, 1951) has been at the forefront of Palestine’s heritage conservation for over twenty years. Born in Damascus, raised in Amman, and with an architectural degree from the American University of Beirut, she permanently moved to Ramallah in 1981 after a short visit to her father’s Palestinian homeland. She is the founder of Riwaq Centre for Architectural Conservation, the first centre for the protection and restoration of architectural heritage in Palestinian towns and villages.

Riwaq is a centre for architectural conservation and restoration of architectural heritage in Palestine. | Photo via Spatial Agency

The renovation of Birzeit’s historic centre by Riwaq was done through physical restoration and innovative activities. | Photo via Spatial Agency

Riwaq’s work has been of great importance for the region, where military occupation and limited consideration to historic buildings have compromised the built landscape. The organisation’s goal is to preserve the built fabric as well as to raise awareness of the region’s rich cultural heritage and collective memory. Amongst Riwaq’s most relevant projects is the Registry of Historic Buildings, consisting of a comprehensive survey of more than 400 buildings in the West Bank and Gaza from 1994 to 2004, followed by the 50 Villages project, a programme aiming at improving living conditions in the identified places through services and infrastructure.

The Akshay Pratishthan School was designed to meet the evolving needs of differently abled children through a more organic architecture. | Photo via Architects Web

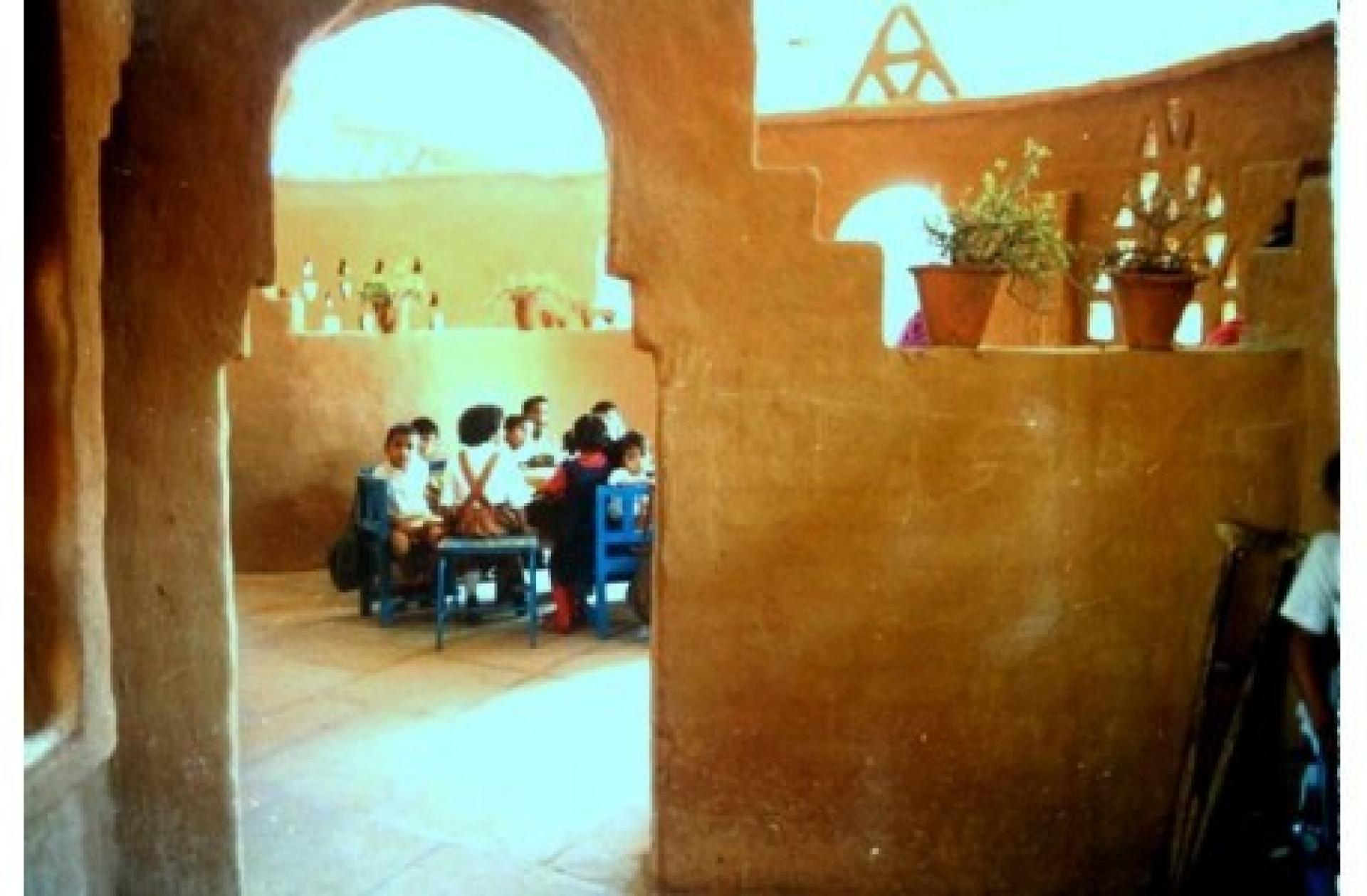

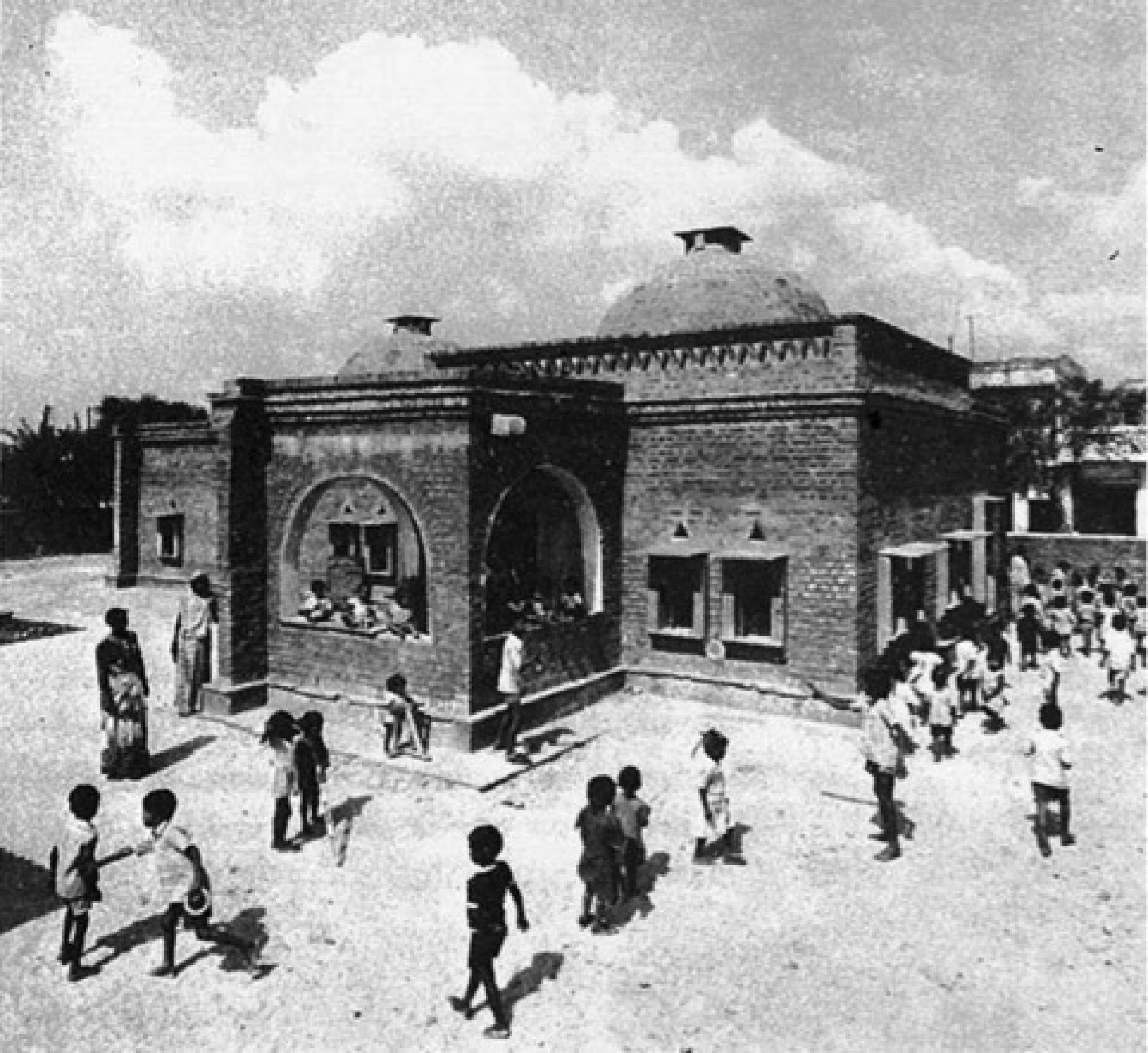

The School of Mobile Creches by Revathi Kamath explored the use of bricks in an innovative way. | Photo via Architects Web

While almost half of registered architects in India are women, architectural merit is still mostly attributed to men; the internationally acclaimed works of Charles Correa and recent Pritzker prizer Balkrishna Doshi first come to mind when referring to Indian architecture. Women in the profession are slowly gaining recognition. Such is the case of Revathi Kamath (Orissa, 1955), an architect working between tradition and modernity, whose approach to design is in line with that of other contemporary female architects. Trained in architecture at the School of Planning and Architecture in Delhi and founder of Kamath Design Studio, Revathi’s architecture is first of all driven by an eco-friendly agenda. She is best known for being a pioneer in the use of mud and adaptation of local construction techniques for her more modern buildings. Her practice’s projects are varied in scale and nature, ranging from schools, to community centres and private houses, but all acknowledging traditional crafts and materials.

Charna Furman is a leading figure for rehabilitating Montevideo’s historic centre and an advocate of women’s rights in the city. | Photo via Un dia uno arquitecta

Uruguayan architect, academic and activist Charna Furman (Montevideo, 1941) has been leading the discourse on the urban requalification of city centres, housing and women’s right to the city in Latin America over the past decades. Graduating in architecture from the Universidad de la Republica in Montevideo in 1978, she is best known for her contribution to the pioneering project MUJEFA, a cooperative housing for single mothers in the historic centre of Montevideo promoted by the municipality of the city in the early 90s. Through this highly political and innovative programme, Charna insisted on the importance of restoring the built heritage in neglected city centres, in particular through the introduction of collective housing, and to give women a central role in urban regeneration.

Mujefa is a collective housing for single mothers in a restored building in Montevideo’s historic centre. | Photo via Un dia una arquitecta

She was a political prisoner from 1975 to 1980 and this experience had an impact on the nature of her work. Her deep involvement in social causes for better urban living conditions and extensive research on urban poverty through a gender perspective is also reflected in her academic work as a university teacher and participation in various organisations. She was one the International Habitat Council’s Women’s Network in 1992, a founder of the Housing Institute for Women in 1994 and took part in the United Nations Conference on Women’s Monitoring Commission on Gender and Poverty.

Lavinia Scaletti is an architectural and urban designer living and working in London, with previous professional experience in France and Chile. Between the hours spent working full-time in urban design at Publica, she undertakes independent projects and research, largely as an extension of her previous university work at the Royal College of Art, investigating issues of housing and urban development. Some examples of her work are the proposal for an alternative housing typology for Wembley or the study of possible solutions to prevent the demolition of Wards Corner Market in London. Her master thesis project Zip City: Houseless not Homeless, also presented for the Future Architecture Platform, is an urban programme exploring a new way of living in cities without a house, redefining the concepts of ownership, sharing and home. Photo Domen Grögl