Atelier Art(i)leria

Elian Stefa is a Tirana based architect and curator, working on exploring ambiguous territories and the revitalisation of abandoned spaces. He has exhibited or curated at the Istanbul Design Biennial, New Museum NYC, EXD/Lisbon, and participated at the Albanian Pavilion at the 13th Architecture Venice Biennale with Concrete Mushrooms, a project which transforms Albania’s abandoned bunkers into infrastructure for tourism.

Photo © Alicia Dobrucka

His project proposed for Future Architecture was dealing with the demilitarization of an abandoned bunker island: Sazan. On the island, while it was nearly impossible for citizens to approach due to the strategic military role, the base was home to a population of over 3000 soldiers and their families, with a primary school, a hospital complex, and several neighbourhoods.With the fall of the communist regime in 1991, the island became almost completely uninhabited, leaving dozens of buildings, kilometres of underground tunnels, and thousands of concrete bunkers haunting the hills and beaches of the island. Elian, with whom I met at the last year’s Future Architecture in MAO Ljubljana, explained the idea of decolonizing military infrastructure for bridging the connection and creating dialogue in cultures scarred by conflict.

Elian, what is your profession?

ES: At this point it is quite difficult to pin point a specific profession, I can say I have a multidisciplinary approach straddling between architecture, art, and NGO work. Mostly what I do is related to examining the territory, and how that has changed because of politics, or changes in social dynamics. I’ve been working on the transformation of bunkers in Albania, on the communist heritage in the territory, and how that has impacted the transition from the communist system to the current one.

You are from Albania; how many countries have you been living in?

ES: My parents decided to emigrate when I was quite young, my youth and mostly my foundation as a person happened in Canada, while as a professional, my foundation is in Milan. These three countries, Albania, Canada and Italy would be where I always feel at home. Currently I’ve been back in Albania for the last seven years, as I’ve been doing a lot of research which was connected to the country so I thought that I had to return after many years of living abroad. Nonetheless, I would say that I feel as more post-national than belonging to any specific country.

How many languages do you speak?

ES: Four. Albanian is my first and my parents’ language, Greek because I learned it when I was very young and living there, English learned in Canada and Italian in Italy. This also taught me how to quickly learn titbits of other languages during my work, because I had to deal with specific contexts, where people didn’t necessarily speak your language, so you need to adapt.

Photo © Alicia Dobrucka

Can you explain more about bunkers in Albania, and the Concrete Mushrooms project which you introduced after studying the topic?

ES: Being born Albanian and always living somewhere other than Albania, I would go back very often and always bring friends along. But what did the landscape of Albania look like in those years? It was full of bunkers, everywhere. During the regime the State used to push propaganda about the 750.000 bunkers to protect Albania, while in reality that number was closer to 200.000, which for a population of three million is still a huge number if you think about it. So, my friends would ask me what these strange kinds of mushrooms are, made of concrete and spread all over the country; and I started to see things from their point of view, researching the potential the bunkers could have instead of the stigma they carried from the past.

Photo © Alicia Dobrucka

This led me to explore the possibility of using them as an icon in the service of tourism. I started understanding the value of these objects as an identifying mark of the Albanian territory, because if you took a photo outdoors there was most likely a bunker hidden somewhere in it, almost like a game of “Where’s Waldo?”. During my studies at the Politecnico di Milano and under the supervision of the course leader of the time, Stefano Boeri, together with Gyler Mydyti we developed a DIY transformational guide for these shelters. It was basically a guide that you could download, and it instructed you how to transform a bunker located in your backyard and finally make the it useful, since the bunkers fortunately were never used in a war.

Photo © Alicia Dobrucka

What was a purpose for the tourism?

ES: Due to our ex-dictator’s extreme isolationism, until recently Albania was always thought of as an impenetrable or even faraway place, so I thought it was quite important to take a symbol from the communist period which was emblematic of this distance and paranoia, and overturn its meaning, creating from it a symbol of welcoming and openness. So Concrete Mushrooms is not a very concrete (ha!) architectural project, but more an intellectual stimulation and a set of instructions. It was the first project that dealt with bunkers with an investigative and research approach, trying to shed some light and find some meaning on the subject. Concrete Mushrooms itself never transformed a specific bunker but many other projects took it as a reference. Being an open source project, this was quite easy because all the materials were meant to be distributed, remixed and rehashed by anyone. Other bunker related projects are for example Converscene by Niku Alex Muçaj,Bed & Bunker by Polis University architecture students to name just a few. Concrete Mushrooms did an important job in raising awareness locally and internationally regarding the bunkers, their history, and their potential.

Photo © Gerta Xhaferaj

What does the presentation in Venice Biennial from 2012 mean to you today?

ES: I think that was a very important year for the project, that was also kind of the conclusion of the project with the publication of the book by dpr-barcelona and it’s launching at the Albanian Pavilion at the Venice Biennale in 2012. Ethel Baraona Pohl and Cesar Reyes helped me to transform the thesis, personal research and website into the published book, which is a really beautiful object that I really treasure to this day. The publication of the book combined with the documentary film, which travelled to half a dozen film festivals until that year, concluded the cycle of investment on my part for the project.

How did you meet Cesar Reyes and Ethel Baraona Pohl?

ES: At that time, I had the opportunity and great pleasure to work with Ethel as associate curators for Adhocracy at the 1st Istanbul Design Biennial, which was curated by Joseph Grima. There’s where we met first and where I found out about her unique love for books. Further discussions while working for Adhocracy produced the book and the friendship. I am really excited about how far they have come along since then, especially since their partnership with Future Architecture Platform and the Archifutures series which I find spectacular.

You were also part of the Future Architecture Platform?

ES: Yes, it was an incredible experience! With ‘Atelier ARTiLERIA’ I was able to present my research on Sazan at the Future Architecture Exchange 2019 to some of the brightest minds in architectural research and FA’s partner institutions. There has been a pretty important development in the territory of Albania since the Concrete Mushrooms book was published, which is that a lot of bunkers have been systematically destroyed, possibly to erase the memory of the difficult chapter of our history.

Photo © Janez Klenovšek, MAO

Nonetheless it is important that they still serve as a testament to the paranoia of extreme dictators, of useless infrastructure and misguided ideology. Today, the only locations where we can still see the impact that these bunkers had on the landscape, is in protected natural parks or areas that you can’t easily reach. Places like the Dajti National Park near Tirana, the military bases near Kepi i Rodonit, or the forefront bunker towards the West, which was Sazan Island. During the 1970s and 1980s the island hosted 3000 soldiers and about 300 of their families. This was a gigantic investment for the State because the island itself doesn’t have very much water, which meant that potable water for over 1000 people had to be brought in with cisterns every day. Now the island lies almost completely abandoned and with the contemporary ruins of about two citadels, a hospital complex, schools and what I think are the seeds to make life of a remote community possible.

What is your development strategy for Sazan island?

ES: In recent years Albania has become very focused on tourism, with rapid development which more often than not is very near-sighted or destructive. Sazan remains one of the last segments of the Albanian coast untouched by the turbo-development typical of the Balkans. Since 2017 Sazan has opened its doors as an open-air museum with boats from the Vlora Bay going to the island daily during the summer season, thanks to a collaboration between the Ministry of Tourism and the Ministry of Defence. From a few hundred in all of 2017, the number is now over 1000 tourists visiting the island every day in 2019, which has already started polluting the island’s pristine nature. In earlier years there were also rumors of Sazan becoming a giant casino.

The aim of ARTiLERIA is to protect the island from these extreme forms of development and instead utilise it not only as a museum of our ex-dictator’s paranoia, but also enrich it with an active platform for applied research in contemporary art and architecture, able to gradually transform and give a new meaning to the territory of Sazan. The island would be representative of the development that we want to see in the future throughout the remaining coast. Being a closed system, one can see the impact of any kind of human action very quickly.

Photo © Gerta Xhaferaj

If we manage to find a balanced approach to live on that barren island through educational workshops, for example solving the water problem, then these experimental strategies can be applied on the main land as open source solutions. The long-term plan is to create a summer school on the island guided by residencies for architects and artists in collaboration with students who “invade” Sazan periodically and little by little transform the island through an active creative laboratory during the summer months.

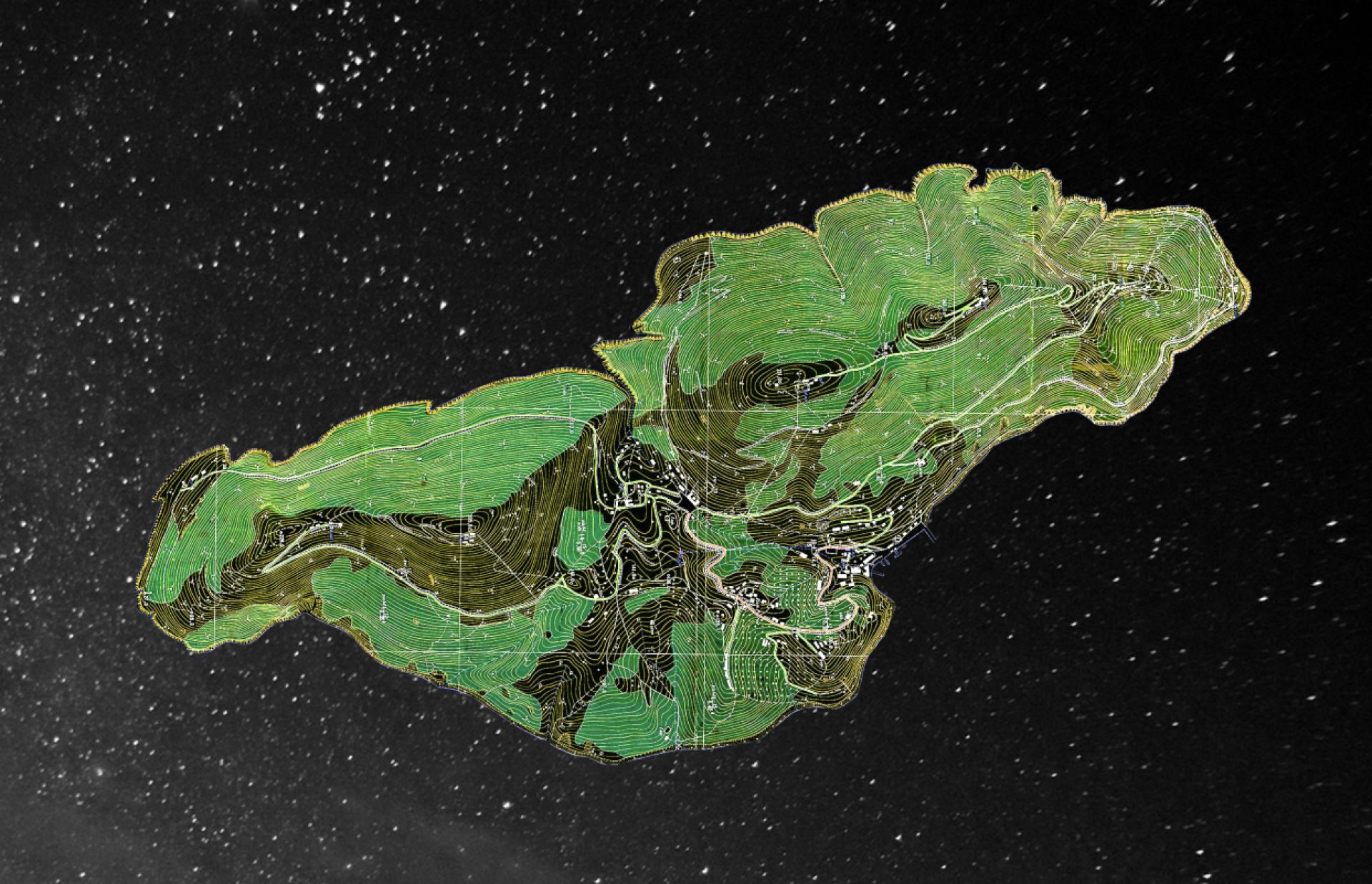

How big is the island?

ES: It’s about 5 km by 2 km, a little over 5 km2, but it has a very rugged and steep character. It would take at least a couple of days to hike all of the island in its current wild state.

Photo © Gerta Xhaferaj

You were talking about a very progressive topic, that is the lack of water; how did the locals understand it?

ES: Although there is a lot of natural water around the Vlora region where Sazan is located, as there are springs all over, the infrastructure is very lacking. People still have water on a running tap for only a few hours a day, and they’ve had to install their own personal reservoirs since the early 90s until even now in order to use water for the rest of the day. Everybody is really aware of the importance of infrastructure by how often they have to rely on their own solutions.

So you’re aiming for other ways of tourism, a critical one instead of mass tourism?

ES: We’ve seen mass tourism in other places like Spain, Greece, Cyprus in the past, and the development models of the 1960s, 1970s and 1980s. We’ve seen how they’ve failed and how many of these territories are unsustainable now. Going back to Sazan; in 2010 there was this idea to transform it into a casino island. This action would completely erase the island’s historical significance while destroying the protected fauna and flora. We would lose all lessons that we could learn from past mistakes while making new ones. In order to avoid the wrong development, we have to direct the right development to take its place before it happens. Albania has a uniquely beautiful landscape which is also a reason why I returned there. This is something to be protected and not be taken for granted.

You are bringing these progressive ideas through the eyes of another perspective, which can help to the better development.

ES: I am an architect by training but personally I’ve tried not to build. I think there’s enough of that so far. The best thing to strive for in my opinion is a functional transformation or an adaptive reuse of the existing.

Photo © Gerta Xhaferaj

Through all these cycles you are doing every 5, 7 years changing your environments, you always come back to Vlora; where do you see yourself at the mature age?

ES: There’s only two options for that, it’s either somewhere near sunny Vlora or on a different planet like Mars. Let’s hope we don’t have to go that far.