FOMA 41: In Search Of Theatrical Halls

Lemonot, a tandem that meets between architecture and performative arts to trigger and celebrate the spontaneous theatre of everyday life, is presenting five Forgotten Masterpieces that shaped their modus operandi.

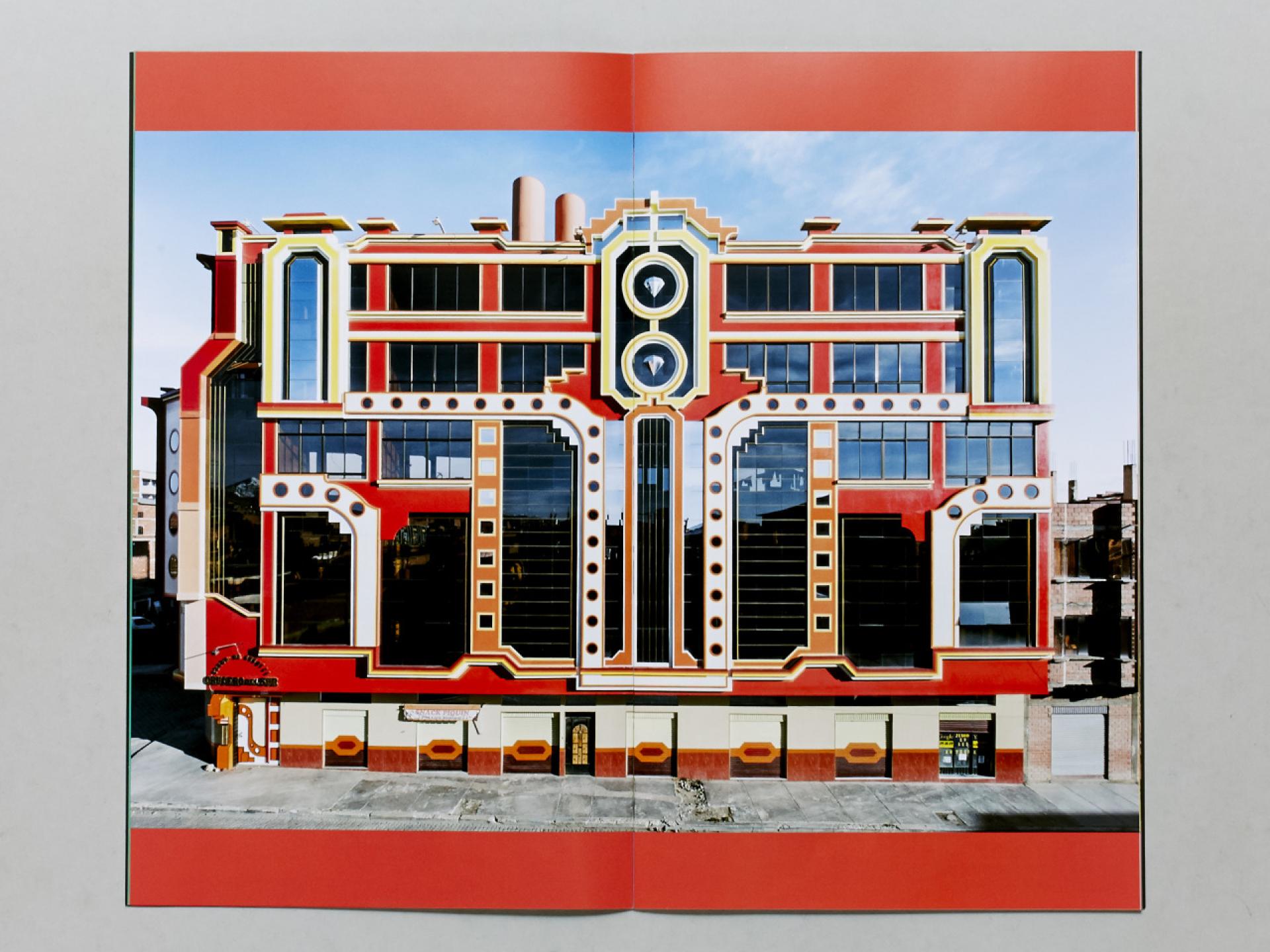

The first cholets were sighted almost fifteen years ago by Freddy Mamani Silvestre. | Photo © Lemonot

Five architectures seem at first glance completely disconnected, they are located in five different cities, designed by different architects, with different programs in diverse historical times. Yet they’re all united by the presence of prominent public interiors with a strong emphasis on the use of unique spatial languages, that make them great examples to investigate how to stage alternative forms of theatricality beyond specific theatre architecture.

In his “Texts on Theatre” describes Jacques Copeau how architecture doesn’t simply contain the drama but produces it, by co-creating its meanings, conventions and aesthetics. Staging a performance, Copeau continues, “is about acting in architecture: it is a practice that demands we pay attention to distance, scale, style, person-to-volume ratio and the immaterial architectures of light, heat and sound. Furthermore, using performativity as a design tool outside the boundaries of fictional scenographies leads to real yet unconventional spatial experiences.”

Indeed, the uncanny linguistic features of these buildings, in terms of geometry, colors, materiality or the clash between architectural layout and designated purpose, affect the way people inhabit them, enabling a peculiar acting in space as the performing of collective rituals and daily routines.

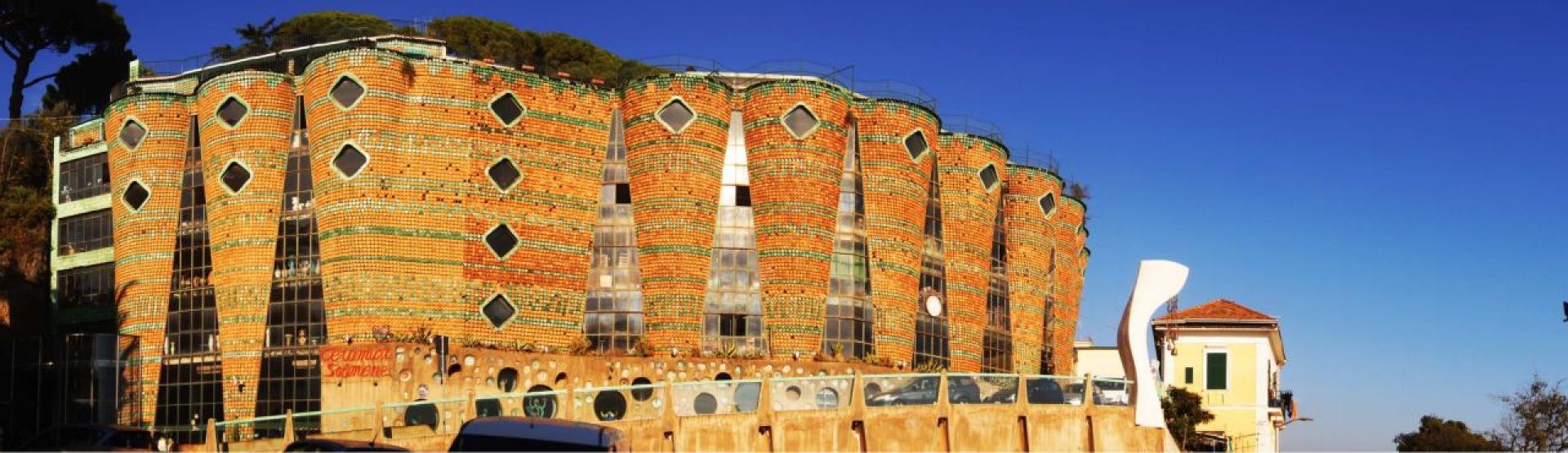

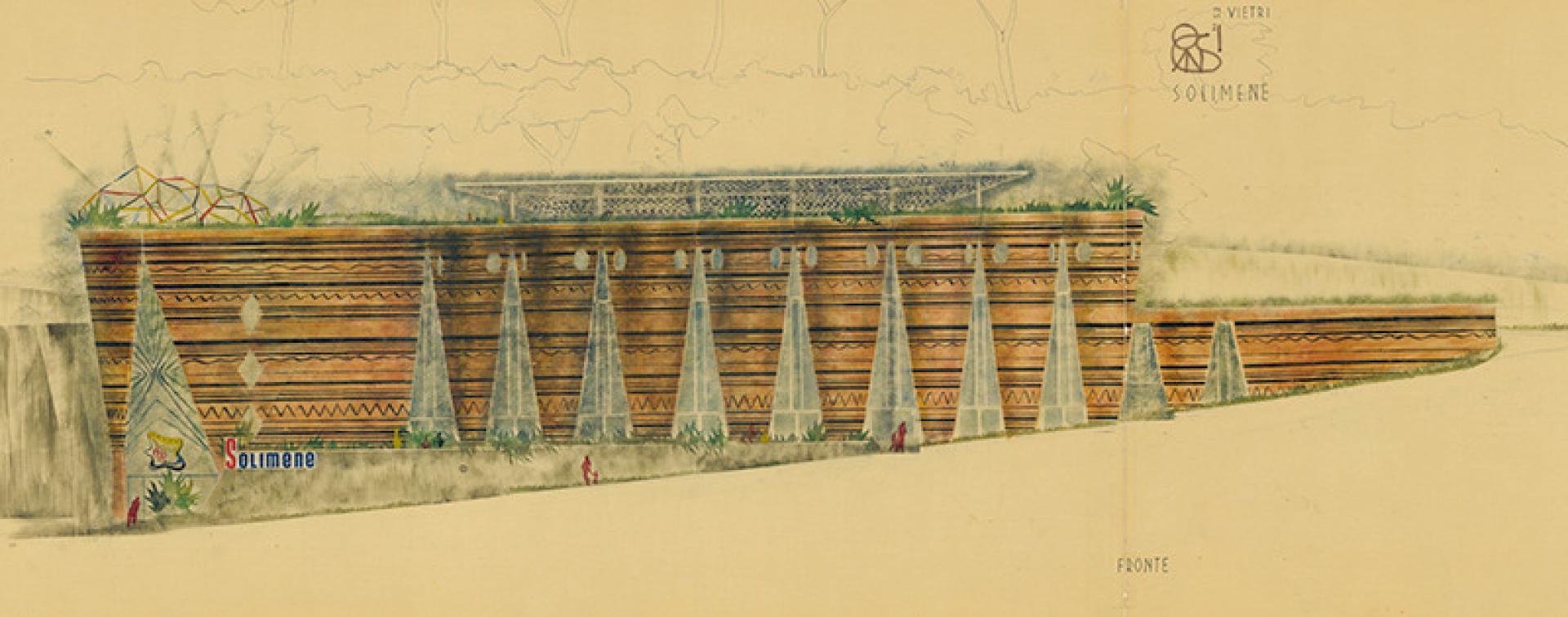

The Solimene Factory was born from the friendship of Vincenzo Solimene, called “Il Vasaio” (the Pottery Maker) and Paolo Soleri, who in 1950 traveled to Italy with the purpose to learn the art of pottery. Solimene entrusted him with the first and only project carried out in Europe, allowing him to design the factory for the production of ceramics.

Circular bases of round terra-cotta vases are embedded in the concrete cladding and decorate the facade. | Photo © Luca Bullaro

The building is as if carved into the rocks overlooking the sea, incorporating the objects it produces. From the outside a bright enamels mosaic in the form of a drapery, almost as a garment giving a hint of what is produced inside, constructed with sixteen thousand waste vases, glazed in copper green or in simple terra-cotta embedded into the facade.

Facade and section. | Photo © Luca Bullaro, © Cosanti Foundation

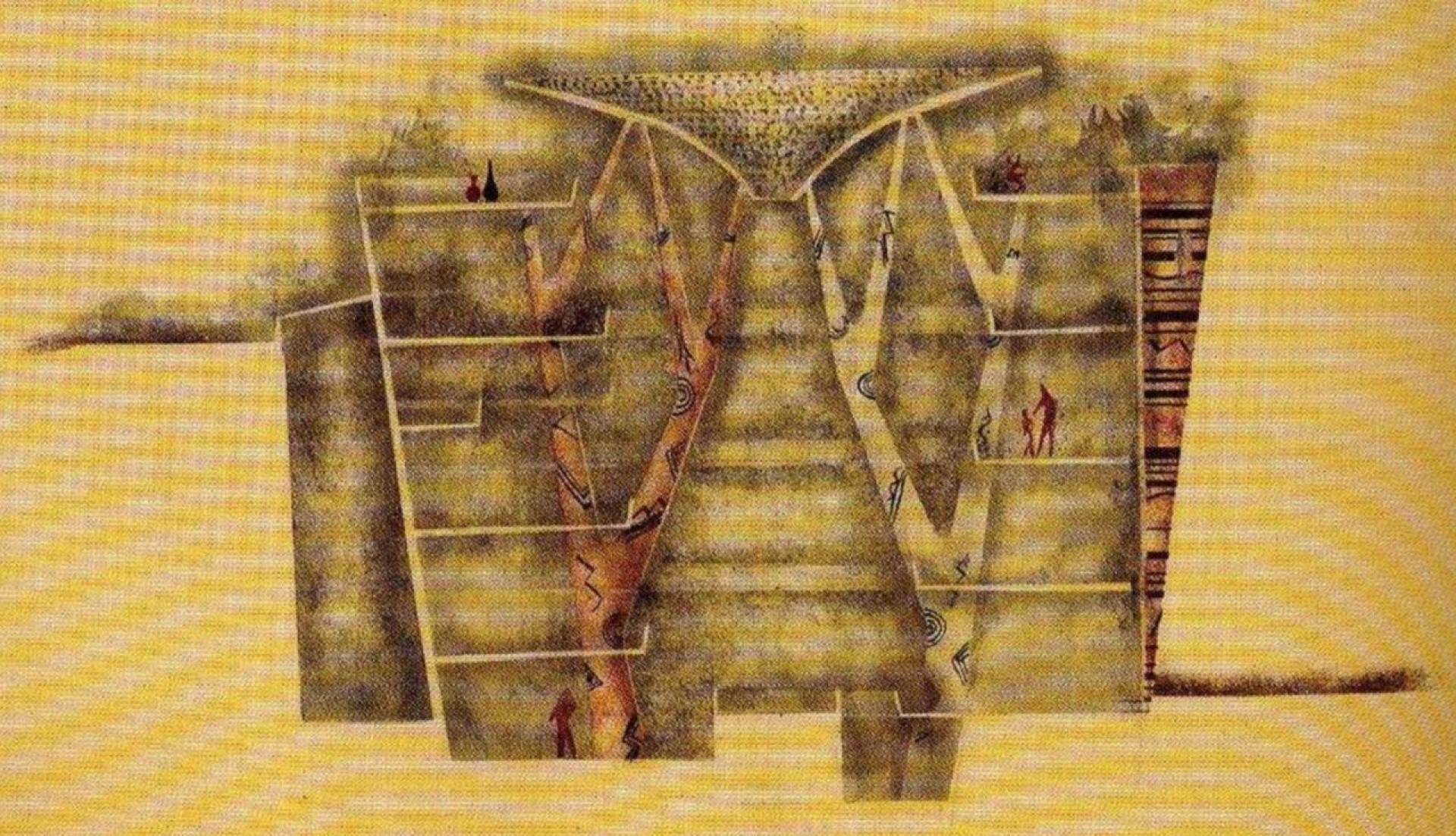

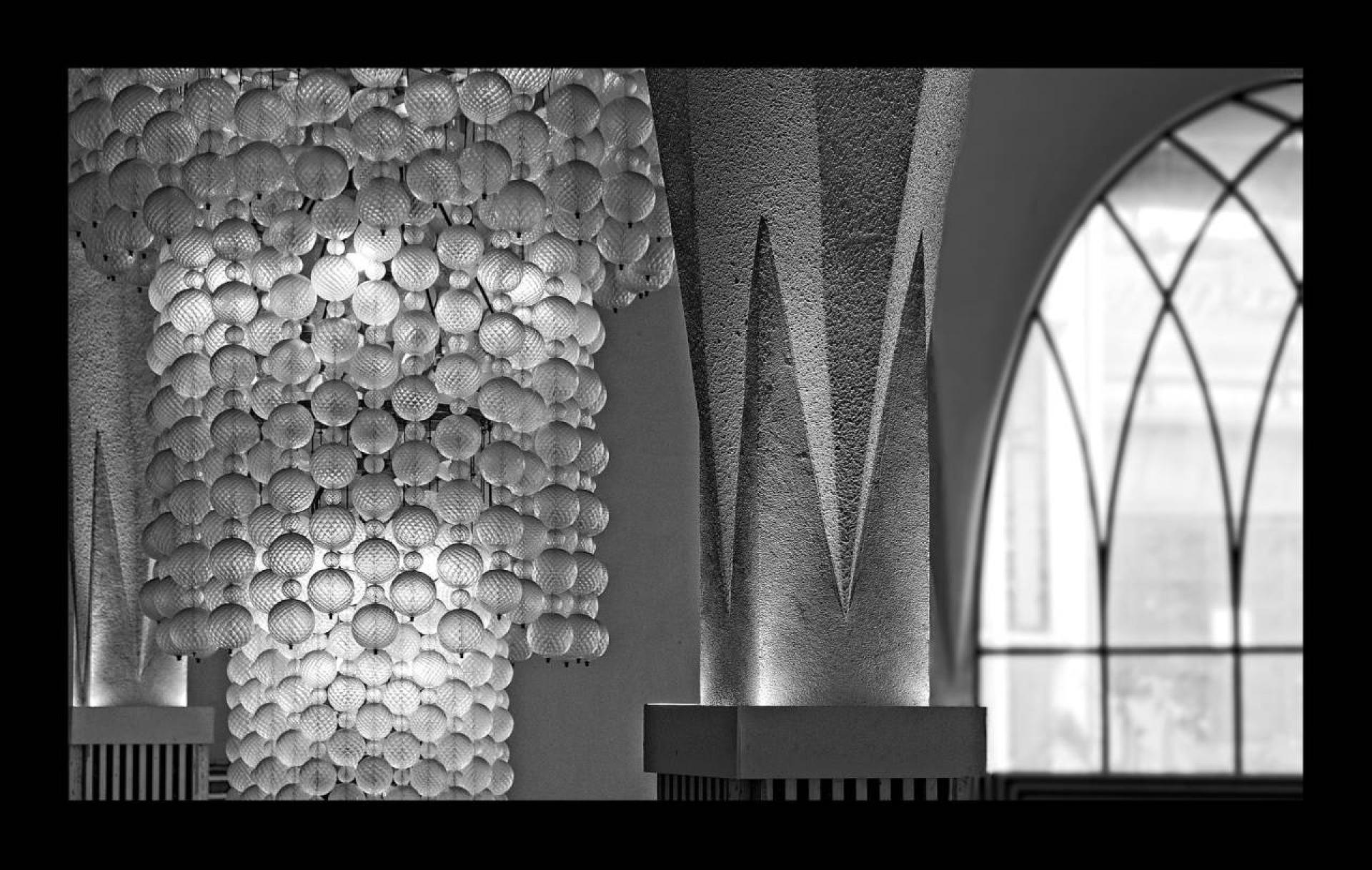

If the outside is wavy and sinuous like the Amalfi domes, the inside is geometric and defines the space towards the center. This fifteen meters central skylight illuminates the objects that are produced every day by expert hands. The interior, flared upwards, follows the same archaic principle of the object that is produced: the growth of the vase on the lathe. The ramp going through the floors, defines the four stages of ceramic processing and allows us to better observe the thousands of coloured and painted dishes, cups and vases.

The pieces are fired at the top floors and slowly come down to be painted in the main atrium, as you descend into the building you see this chromatic and also geometric change - from the material to its final creation. The building accompanies you throughout the production of a single object - starting with the terracotta and gradually seeing its final shape and colours. The objects become part of this scenography, framed in every gaze. They’re simultaneously actors and props that drive the public - constraining you to squeeze and linger among them. It is an architecture that screams the craft made with hands, which is still in full fervor today.

The building received the ASA Architectural Conservation Award in 2012. | Photo © Antoine Lassus

The Scala Theatre in Bangkok was without doubt the grand old theater and the finest movie theater left in Southeast Asia. Named after the Teatro della Scala in Milan, it first opened in 1969, showing the American civil war movie “The Undefeated”. Unfortunately, it has been recently closed down, probably due to the impact of the Covid-19 pandemic and changing consumer preferences.

Its wonder is certainly due to the central location in Bangkok, one of the most chaotic cities in the world. The most interesting part of the building is not the enclosed screening hall. Rather, it’s the covered yet open foyer, whose elegant and geometric interiors are constantly and directly contrasted by the noise of the mopeds, by the smell of street food grills and tropical plants that can be seen from the windows. Its relationship with the city is definitely theatrical.

The foyer consists of a huge domed ceiling, set up with bronzed art deco flowers. | Photo © Antoine Lassus

In the past these kinds of theaters were usually situated in city centers and markets, where they became community gathering points as they supported the theater and the community. In this line, the foyer of Scala theatre acts as a proper public space, as a shaded portico that offers shelter from the heat of Bangkok. This is reflected in its overwhelming but at the same time welcoming decorations - columns that drop from the ceiling, lights in the shape of geometric flowers, floors and walls covered with velvet fabric. Thai culture is eccentric, it is flamboyant and greets you by dominating your senses.

The architecturally significant cinema’s Art Deco stylings and interiors were designed by Jira Silpkanok, which with its velvet curtains, veteran ushers, and vast auditorium, evoked the golden age of film exhibition. Specifically, the foyer consists of a huge domed ceiling, set up with bronzed art deco flowers. You are conquered by the vaulted windows that frame Bangkok as a choreographed spectacle - by the different types of textures both on the base of the columns outlining the shadows. Two stairways converge at the top taking you to the second floor, while almost touching the long chandelier that illuminates the center. A visionary architecture, where as soon as you enter it seems to be in a ship, or a spaceship.

The Bellini Theater in Palermo was first called Teatro Travaglino, from the name of a Sicilian burlesque mask. A hidden truth is hidden in its name since the theater has had to change many faces throughout the centuries. Destroyed several times by earthquakes and wars and many times rebuilt and renamed, looking for a new identity. What we have today is an incomparable Architectural stratigraphy of historical facts.

The theatre was an open living room in between privately owned palaces where the public could go in for the first time. | Photo © Lemonot

The theater has been literally carved inside a noble dwelling, the gallery and the stage are built between private houses, in fact it is still possible to see the windows of the neighbors that overlooked the main stage. It was entertaining popular operas and due to this fact, the space was constructed around a small stage with few wooden benches. Initially the main gallery had only festive purposes, banquets were set up and dances were often opened; it is only later that great artists were presented and therefore had a primarily cultural purpose.

Destroyed, rebuilt and renamed. | Photo © Lemonot

Over time Marquises of Santa Lucia sacrificed part of their palace to build in 1726 a classic Italian-style theater with 4 tiers of boxes and entirely in decorated wood, it was called the theater of St. Lucia. The need for a more refined theater for the Elitè was entrusted to the royal architect Nicolò Puglia who accommodated more than 500 spectators.

Due to the disastrous earthquake that struck Palermo in 1726, the theater remained closed for several years, reopened only in 1742, enlarged and restored again, incorporating some neighboring houses of the Marquis Bellaroto.

In 1943 during the second world war it was also requisitioned by the US military and used as a movie theater for soldiers. In 1964 the building was damaged by a fire and subsequently recovered thanks to the intervention of the Teatro Biondo Stabile in Palermo and thanks to the professionalism of its director Claudio Grasso who regained the license from the Palermo police headquarters and returned the theater to its original function in 1980 until 2014.

It was reopened as a permanent exhibition venue. | Photo © Lemonot

Since 2019 is hosting a mixed-media installation designed by Alfredo Jarr. This operation led to many controversies - since part of Palermo’s cultural community stated that a theatre should be open only for spectacles and actual plays. The theatre layout and the museographic stage set affect and update each other in a very interesting way: the usual relationship between the proscenium (the place for the spectacle) and the platea (the place for the audience) is inverted, since the public gathers to admire the exhibition from the first, while the artworks are hosted in the latter, emptied of chairs’ rows.

Furthermore, this peculiar theatrical framework, shifting the way we look at the artifacts, activates a spontaneous layer of performativity, otherwise left behind in most traditional museum environments.

The Cistern Chapel or the Sewage Cathedral is a former pumping station designed by chief engineer Sir Joseph Bazalgette and architect Charles Henry Driver. Its construction became necessary in response to the the Great Stink of 1858.

The meticulous designs and bright colors have made the Crossness Pumping Station a real Victorian-style gem. | Photo © Lemonot

Its construction became necessary when the Thames became particularly polluted enough to raise a putrid smell throughout the city. The situation was aggravated by the unusually hot climate that hit the English capital and made the stench even stronger and unpleasant. To solve the problem, the Bazalgette plan consisted in the construction of two sewers to be placed in the outermost areas of the city. One of these was the Crossness Pumping Station which, at the time, had the function of draining the putrid waters to the east by running clean water into the Thames.

The complex is covered with decorations surrounded by cast ironworks forming columns rising up from the ground floor. | Photo © Lemonot

An architecture is made of joints and unconscious paths following geometric shapes and colored corners. The light is drawn to the central octagonal arcade, which supports a frieze of regimented yet twisting leaves and tendrils and on each column flowers, leafs and fruits decorate the capitals. At the time, the highly crafts fancy curlicues of cast iron weren’t seen as an unnecessary expense - it was the first time for such functional purpose to build with opulent and organic decoration of this kind.

Indeed, there is a great sacral charge within the main octagonal space that encourages the people to gather between the columns, inviting you to look up but also to hide among the industrial spaces - that become almost domestic. All four engines were named after members of the royal family; Victoria, Albert Edward and Alexandra: for this reason the choice of colors, materials and different patterns follows a specific narrative, becoming a built embodiment of their personalities. The spatial elements are actually personified, transformed into architectural characters.

Sprawled over a high plateau above La Paz, El Alto is arguably Latin America’s largest indigenous city. At an altitude of 4800 m, colorful buildings arise and geometric facades are visible from the teleferico travelling above the altiplano. The first cholets, also called New Andean architectures, were sighted almost fifteen years ago by Freddy Mamani Silvestre. Since then, they proliferated: various architects have appropriated them in terms of style and copied them typologically.

Cholets became expressions of wealth and cultural pride after centuries of oppression and colonialism. | Photo © Lemonot

Cholet is a portmanteau of the high-class chalet - the pitched roofs of these mansions resemble the ones of Swiss cottages and the derogatory cholo, a racist slang for an indigenous person. Mamani ‘s buildings have a common language, two or three storey and a ballroom on the highest ceiling room filled with Andean symbols, casted columns and windows with different geometrical profiles cutting the whole space. Using the colors of textiles are tracing inspiration from traditional garments and folkloric masks. These ballrooms are identified not only through iconographies but also by the use they make of it - from dances to ceremonies, to domestic inhabitation, to basketball courts or swimming pools.

Cholets are always designed in close contact with the buyer, triggering a personal and almost process of embodiment of the owner with the building itself. The building is to produce income. On the roof is our own home. The spatial experience can be read in completely opposite way, during the day the light from outside is absorbed by the colors and it seems to be in a video game, a confetti space. As soon as darkness falls, the LED lights direct you into the ballroom and surround every architectural element.

Not only the architecture itself is ornamental but the eccentricity with which the Aymara use and change the program of the space. The one of cholets is a controversial phenomenon, that nonetheless portrays the political, social and economic contemporaneity in Bolivia. On an urban level the cholets have become a symbol, recognizable monuments - able to immediately recall Andean identity nationally and internationally. Ultimately, the architecture of Crucero del Sur speaks the same language of the ceremonies that take place inside it. In these exuberant interiors, matter and performance achieved an absolute reciprocity.

Sabrina Morreale and Lorenzo Perri are architects, educators and co-founders of Lemonot, a design and research platform based in London. Hungry observers and compulsive collectors of anthropic mirabilia, they’re interested in all those iconographic gestures that enable the mutual immanence among objects, bodies and rituals. Their academic research focuses on contemporary folklore as a trigger for unconventional spatial languages, between geometrical abstraction and material figurativism. They’re Programme Heads of the AA Visiting school El Alto and currently teach at the Architectural Association and the University of Applied Arts Vienna.