Paul Williams - I Am A Negro

"I am a Negro" is Paul Williams’ essay written for American Magazine in 1937, which speaks the power of minority representation.

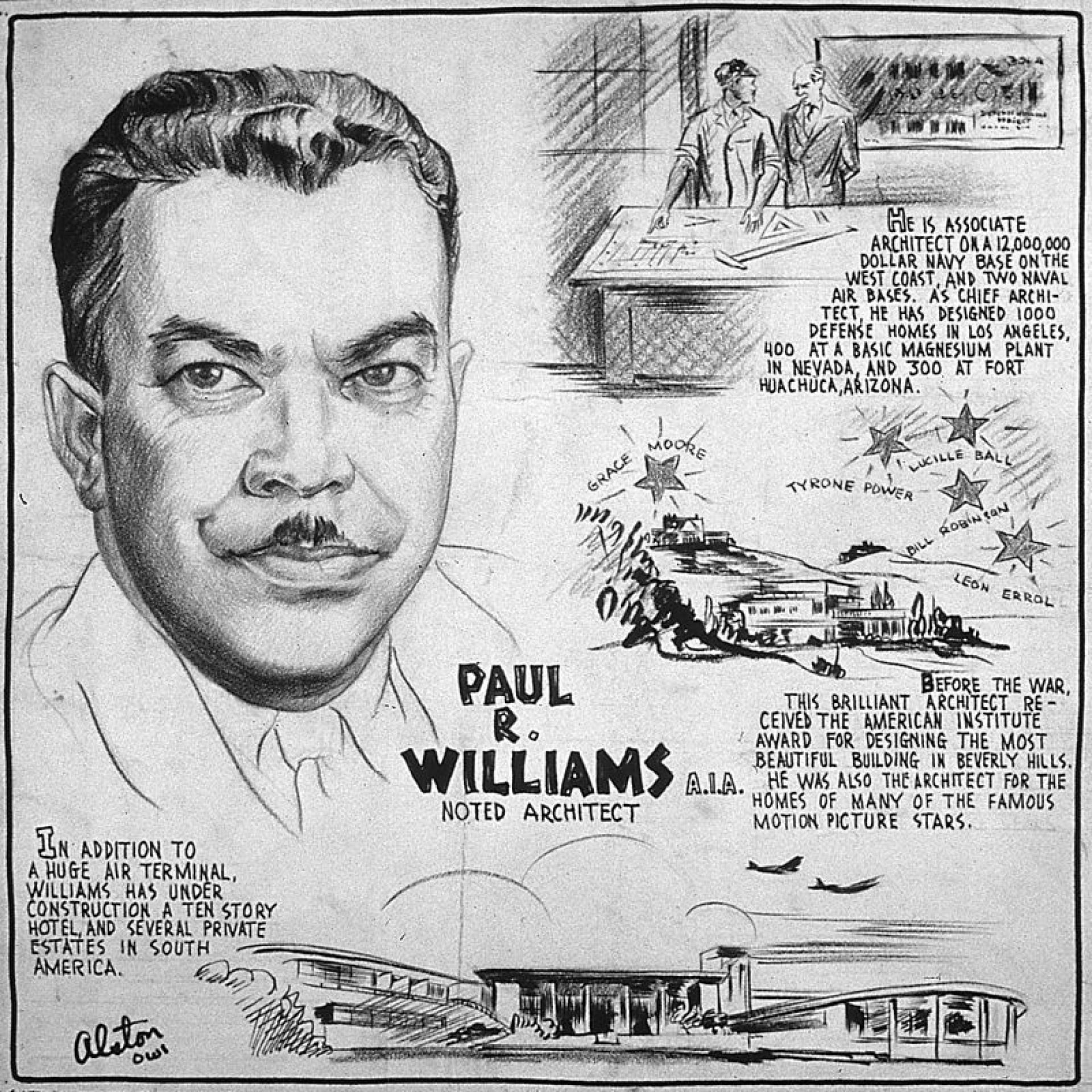

Poster from Office of War Information; Domestic Operations Branch, News Bureau from 1943 | Drawing by Charles Alston

Even in 1937, representation of minorities mattered. It still does, today, in architecture, where African Americans constitute 13% of the populations but only 3% of practicing architects. Yet, this absence does not imply a vacuum, as the misconception that clients desire designers who share their same skin profile, has not prevented but merely hidden the contributions of black architects. In this shadow lies Paul Revere Williams. A designer of over 2000 buildings around USA, Williams was best known as the postwar designer to Hollywood’s stars, crafting tasteful homes for the cultural elite, including Lucille Ball and Desi Arnaiz, Frank Sinatra, Bill (Bojangles) Robinson, Bert Lahr, and many other prominent Southern California figures. Though his prolific portfolio warrants its own consideration, his ability to be judged by clients on his designs rather than his skin tone is a tribute to the sheer power of his talent.

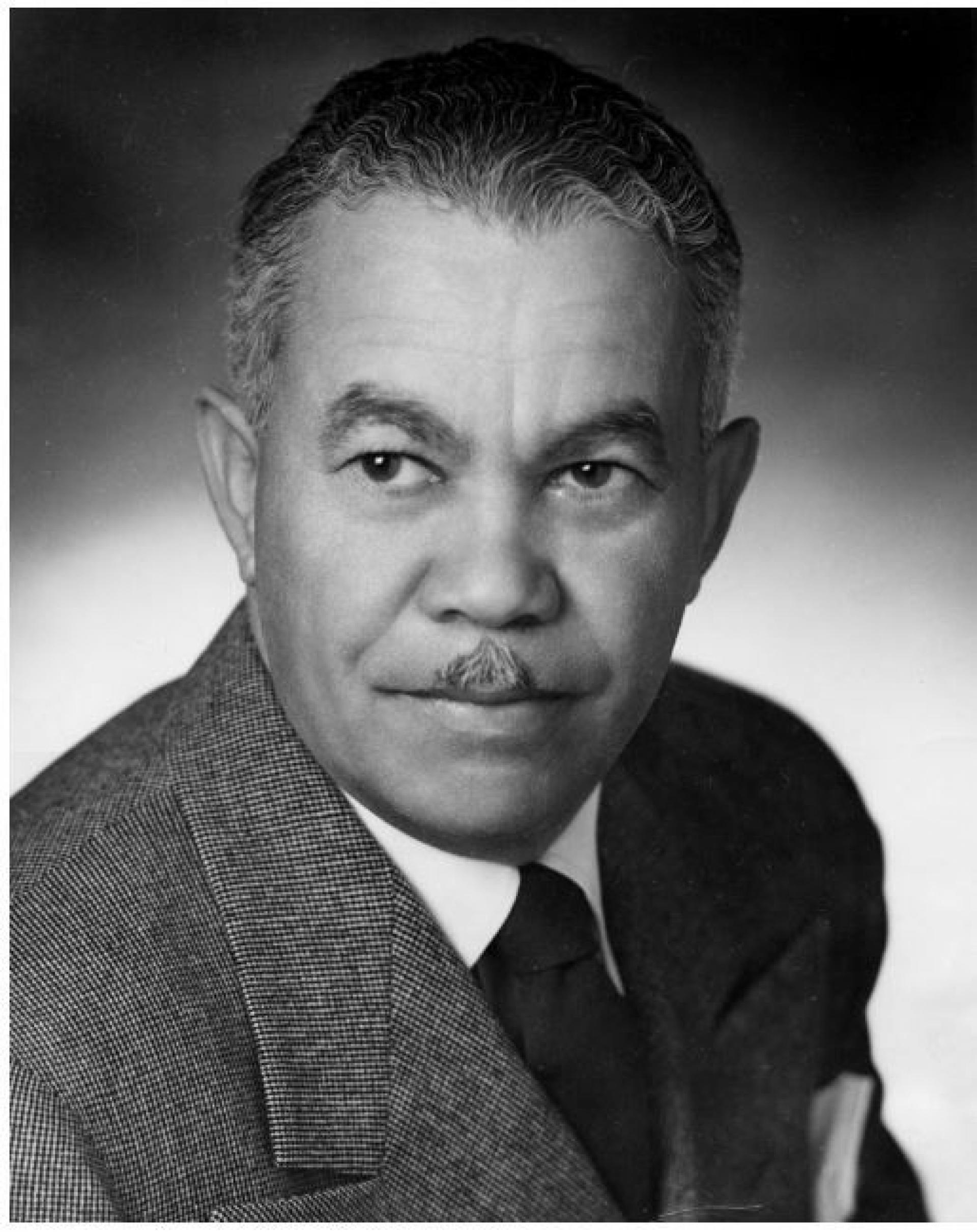

Paul Williams received posthumous the AIA Gold Medal for lifetime achievement in 2017. | Photo via The Paul Revere Williams Project

Born in 1894 to Memphis-natives, Paul Williams was quickly placed into foster care after both parents died of tuberculosis complications prior to his fifth birthday. While apartheid conditions were codified in large swathes of the early 20th Century United States, Los Angeles allowed racial mixing in schools where Williams thrived at the Los Angeles School of Art and Design and later at the University of Southern California. After winning awards for his early designs and serving on the Los Angeles City Planning Commission, he became the first ever African American licensed by the American Institute of Architects in 1923.

Despite the lenient racial attitudes of Angelinos, Williams still spent his early career navigating the complex behavioral conventions around race in America. The success of his career was facilitated by his acrobatic flexibility accommodating the racial discomforts of white clients. Local laws, for instance, often prevented any African American from sleeping a single night in neighborhoods for which Williams was tasked to design. He even developed an uncanny ability to draw upside down so that white clients could sit across instead of next to him. These adaptations were pragmatic to his practice, but Williams was determined to undermine racial assumptions and develop future opportunities for black architects, echoing Dr. King in his essay, I Am a Negro,

“Virtually everything pertaining to my professional life during those early years was influenced by my need to offset race prejudice, by my effort to force white people to consider me as an individual rather than a member of a race.”

Williams also understood that offsetting racial prejudice in architecture extended beyond his own practice and that the continued advancement of black architects also involved the development of black clients. Beyond luxury homes, Williams sought to inspire a new generation of black architects by investing time in exhibitions at historically-black Howard University, eventually even designing a building on campus. Additionally, his devotion to the idea of modern housing as social reform prompted a program where, for $10 USD, Williams would deliver floor plan drawings for a house on any lot, allowing poor, largely black homeowners to afford works of architecture, shifting the perception of whom architecture serves.

Rosa Parks was arrested as she refused to give up her seat in a public bus to a white woman in 1955. | Photo via Underwood Archives, Getty Images

The living room of the Lillen Residence combines organic curvature with the modern lines. | Photo via The Paul Revere Williams Project

These innumerous and diverse commissions resulted in a unique ability to shift between forms and styles of design. Williams’s early work was largely in the classical revival style popular for Southern California homes at the time. He became known for his ability to design a voluptuous stair, proving too alluring for his most discriminatory clients. The Aaron Lillen Bel Aire Residence proves typical of a Williams home, with all the iron work and stucco expected of luxurious early century homes in the area. In contrast to the straight lines of the living spaces, the curvature of the reflected ceiling plan and the stairs emphasize a luscious counter system to the rationality of the modern home.

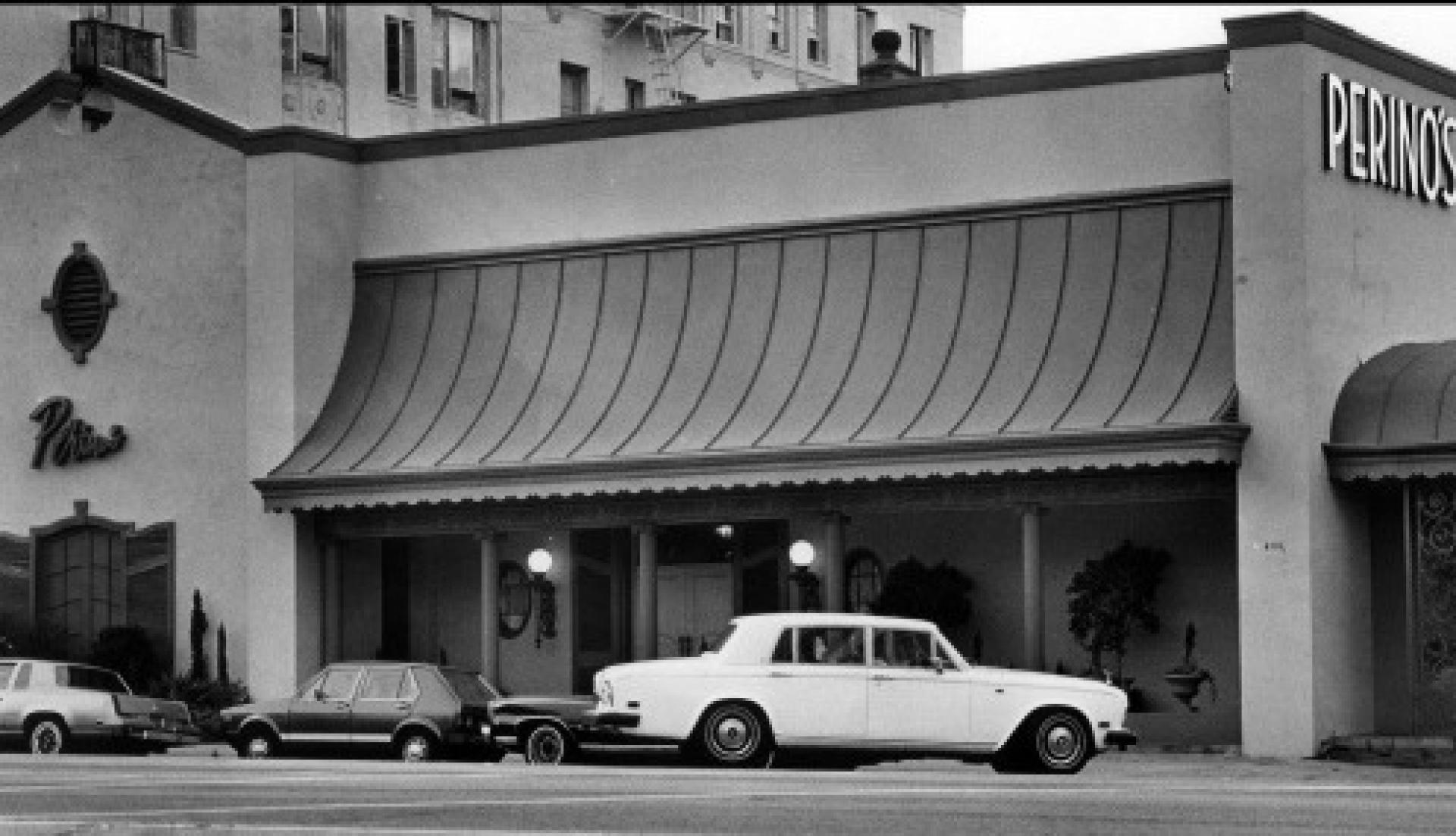

Perino’s classical elegance design. | Photo via The Paul Revere Williams Project

Perino’s Restaurant, a New Orleans-themed establishment designed in 1953, was the most popular restaurant for Hollywood stars during the 50s. In their move to a new location, the restaurateurs’ entrusted the project’s $400000 USD budget to Williams, which speaks to their faith in his design capabilities. The classic fare of Williams’s interior reeked of old world elegance, at odds within peak-new world California. Unfortunately, the project was ultimately for naught as a fire destroyed the building a year after opening.

The Frank Sinatra Residence integrated the newest technologies into Mid-Century Modern tropes. | Photo via The Paul Revere Williams Project

In contrast, the Frank Sinatra House declares itself an early precursor to California Modernism. Williams synthesizes a more historical materiality of stucco and ironwork to the then-latest technologies, including integrating the sound system that fueled many of Sinatra’s infamous parties into the outdoor ceiling. The low profile and cantilevered roof seem an easy first step towards the work of Richard Neutra in the coming years. In spite of its reputation as a raucous bachelor pad, Williams demonstrated his ability to morph between architectural styles and adapt to changing aesthetic and technological tides.

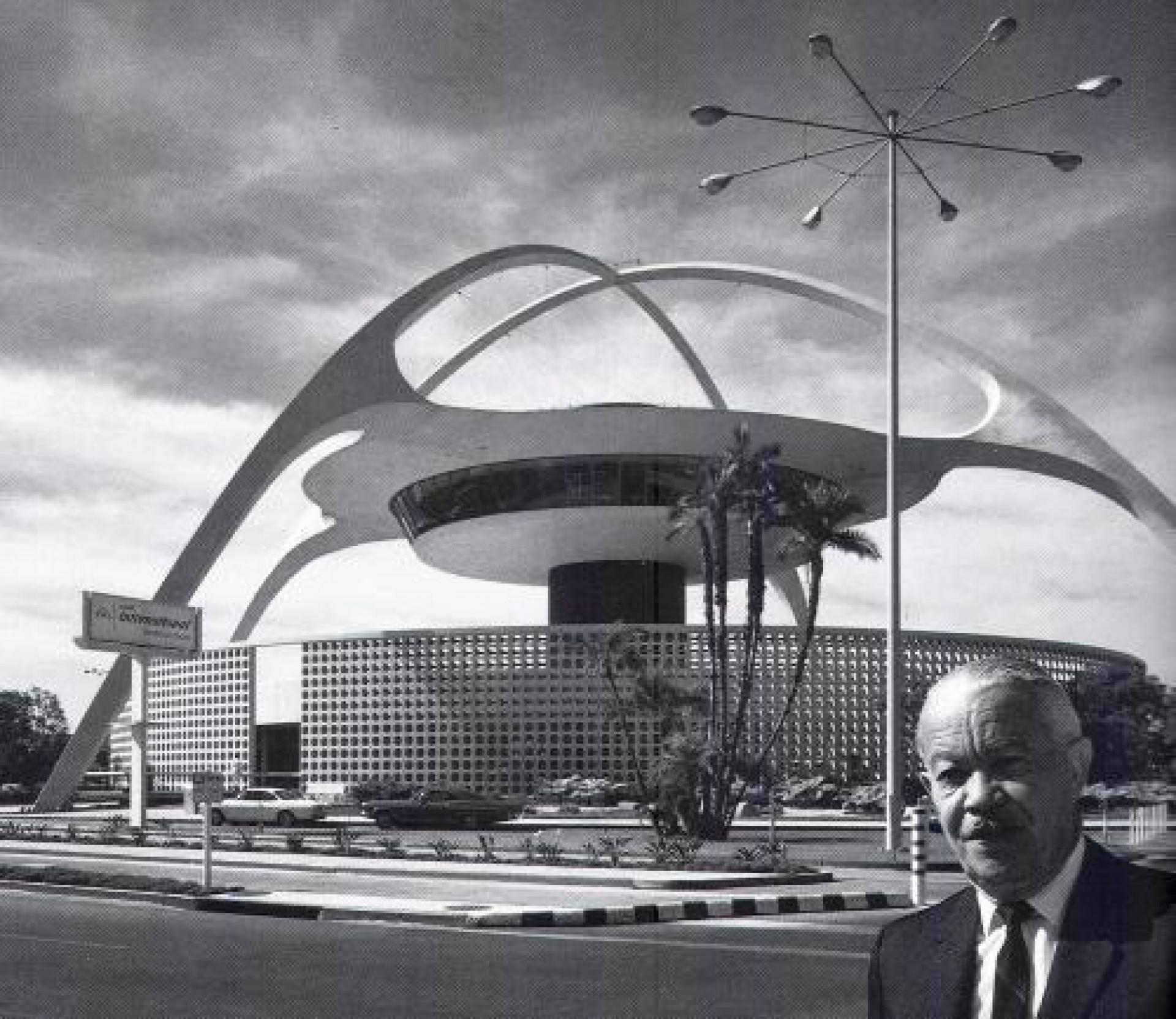

This is never more apparent than Williams’s most public building, Terminal One at LAX airport. Definitively modern, the building, designed by an extensive team in which Williams was a participant, is the exemplar of Williams’s ability to morph between architectural style and approaches.

Paul Williams embraced the organic curves of modernism to design the futuristic Terminal One at LAX. | Photo via The Paul Revere Williams Project

Despite Williams’s numerous architectural achievements, black architects still face immense hurdles just to enter the profession a half-century later. In school, Paul Williams was discouraged from entering architecture, as the prevailing perception was that the black community could not afford designer homes and white clients would be unwilling to work with an architect of color. These assumptions endure today: architects still tend to look like their wealthy, white clients. Though a step in the right direction, the posthumous AIA Gold Medal Award given to Williams celebrates less his lifetime achievements, but acts as a recognition that, as a professional association, the AIA has underserved the black community.

The National Museum of African American History by Adjaye, takes inspiration from African weaving, an architect and inspiration untenable without Pioneers like Williams. | Photo by Bradt Feinkopf

Williams’s true legacy lies in an emerging generation of black architects, like David Adjaye and Francis Kere who are more free to pursue diverse architectural agendas and clients. Starchitects might be maligned generally in architectural culture, but David Adjaye’s fame has combatted the discipline’s representational issues, a next step in exposing and advancing black architecture.

David Adjaye | Photo via Adjaye Associates

Adjaye’s fame has even led to the further cultivation culturally-black projects, like the National Museum of African American History, which acts an amplification of Williams’s work at Howard University.

Kere’s community-focused design, bordering on non-profit work, continues Williams’s quest to extend architecture to black communities. By designing community projects in Africa, Kere further expands the definition of whom deserves architecture. The contributions of pioneers like Paul Revere Williams are directly responsible for these works and the continued acceptance and representation of black architects will rely on their continued success.

Diébédo Francis Kéré is a German-trained architect from West African town of Gando in Burkina Faso. | Photo by David Heerde

—

by T. Craig Sinclar