FOMA 35: Albania - Future Stories For The Past

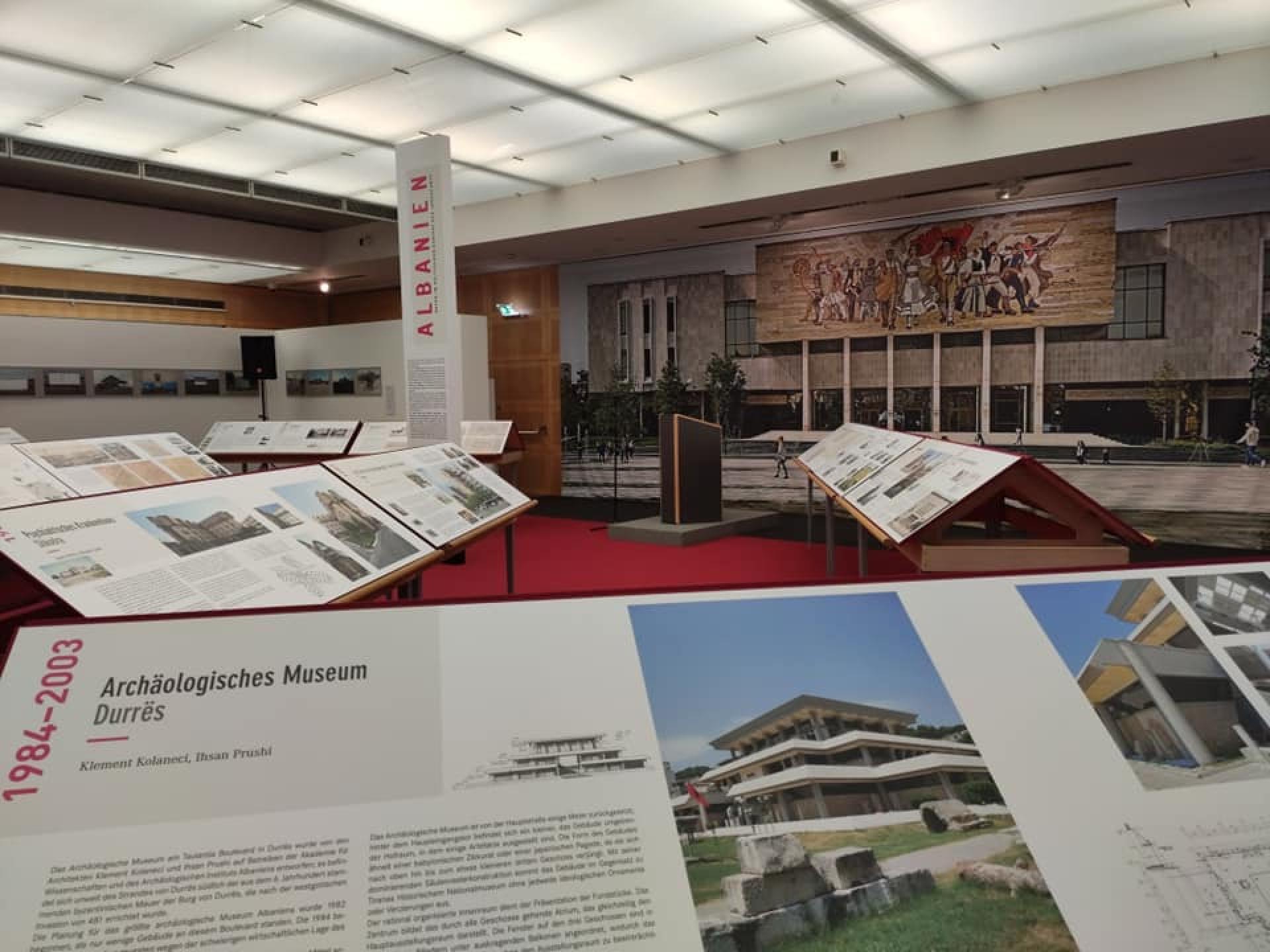

The selection of this Forgotten Masterpieces is developed under the reference of the book Albania - Decades of Architecture in Political Context written by Sotir Dhamo, Besnik Aliaj and Saimir Kristo.

This first volume of FOMA presented by Saimir Kristo include architectures from the administrative and governmental ranks, culture and education buildings, rehabilitation facilities, hotels and hospitalities and remains of regimes.

Authors of the book Besnik Aliaj, Saimir Kristo and Sotir Dhamo (from left).

Albanian projects realized between an intense and particular social and political scene involve buildings from the self-declared monarch of King Zog I, to the colony of Imperial Italy under the fascist regime before World War II, up to the rule of the party of labor and the dictatorial regime of Hoxha.

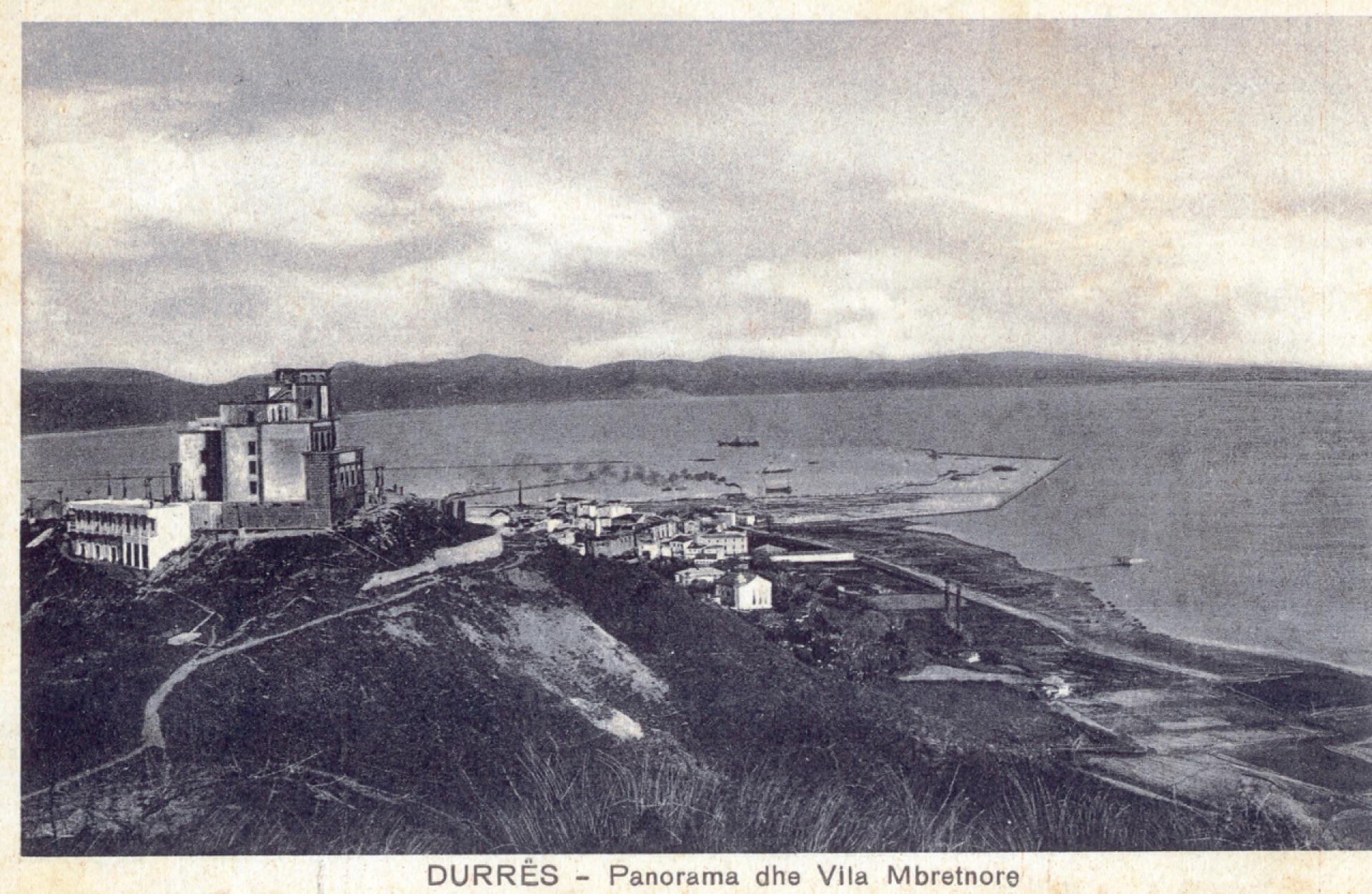

The Royal Villa in Durres constructed by Florestano Di Fausto, Gherardo Bosio, Kristo Sotiri and Armando Brasini was the summer residence of king Zog I and his family. The fashionably styled building has survived as a symbol of the monarchy. According to some sources it was a gift to the king from the business community of Durres, according to another it was given to the king by the Italian government with the intention to strengthen relations between Albania and Italy.

The Royal Villa is situated on top of an adjacent central hill of the city.| Photo via National Technical Archive of Construction Albania

The presence of the kind and his family in Durres, despite his main headquarters in the new capital Tirana, brought about a type of political balance between the two cities and the role they played in the history of the country.

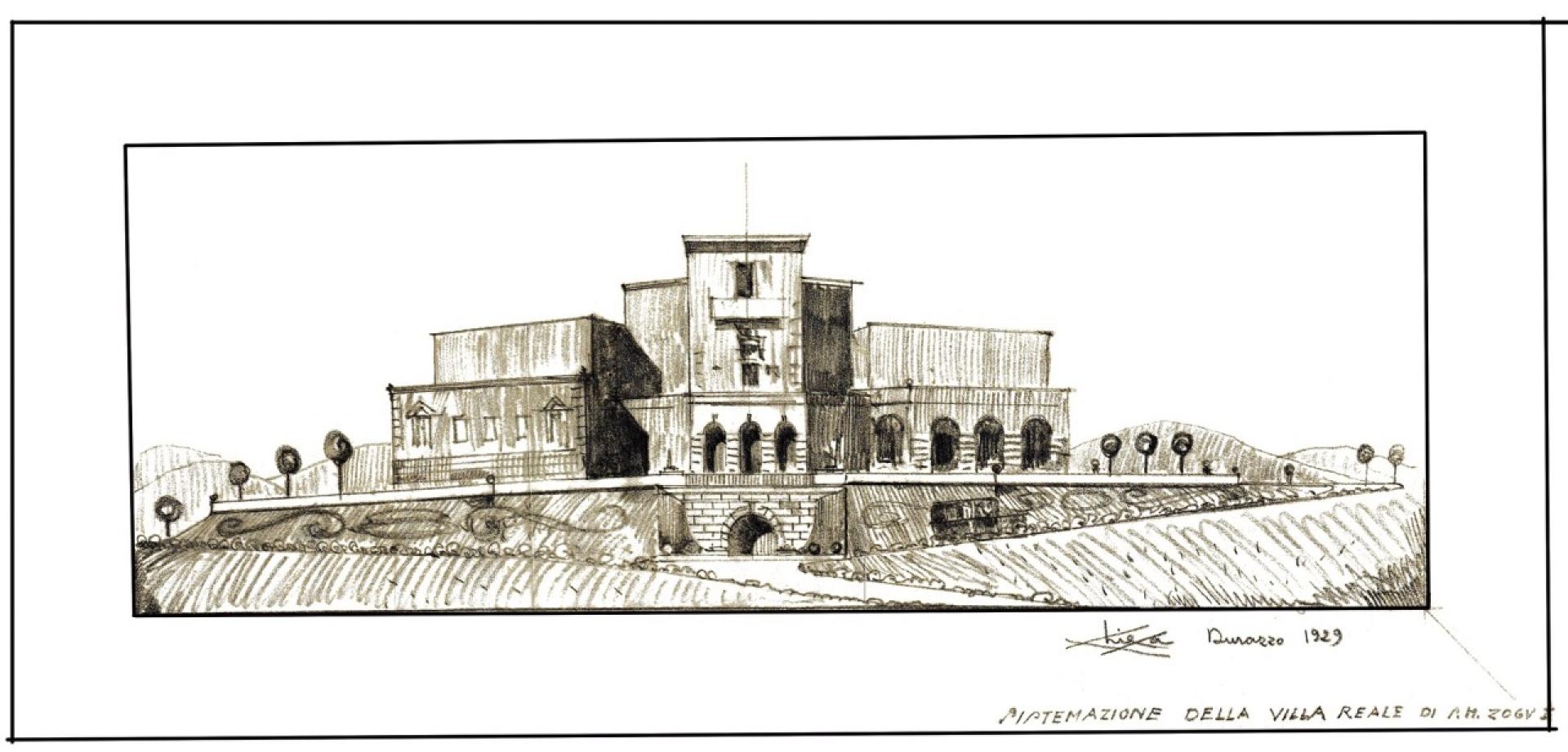

The first concept of the Royal Villa with its own European style was designed by Italian architect Armando Brasini (1929). The final project was finalized by Florestano Di Fausto, assisted by the engineer Antonino Chiesa (1928-1929). Documentation found in the archives show that the original design was in an eclectic style and retained a pre existing structure, which was partially demolished. The intervention of the Italian architect Gherardo Bosio was limited to the interior, transforming the former royal palace into the office of the lieutenant governor as documented in a series of undated sketches.

This building designed by architect Kristo Sotir was later on substituted by the building designed by Florestano Di Fausto. The designs of Bosio and Di Fausto show the dilemma of Italian architects of the 1930s generation, operating between principles of the nineteenth century and rationalism (Giusti, 2006).

With its 360-degree panorama, it offered a view of both, the sea and the land, especially the historic city. Construction of the vila started in 1926 based on the art nouveau concept of the local architect Kristo Sotiri (educated in Padova and Venice) who had previously worked for the Romanina royal family. The works were completed in 1937. After the Italian invasion of 1939 the king and his family were exiled. During World War II and thereafter, the residence was used for government receptions and events. The building was unfortunately looted and damaged during the social and political turmoil of the Albanian rebellion in 1997, and is undergoing a gradual process of reconstruction.

The legibility of this building is based on the contrast of pure volumes on different scales.| Photo via Gizmoweb

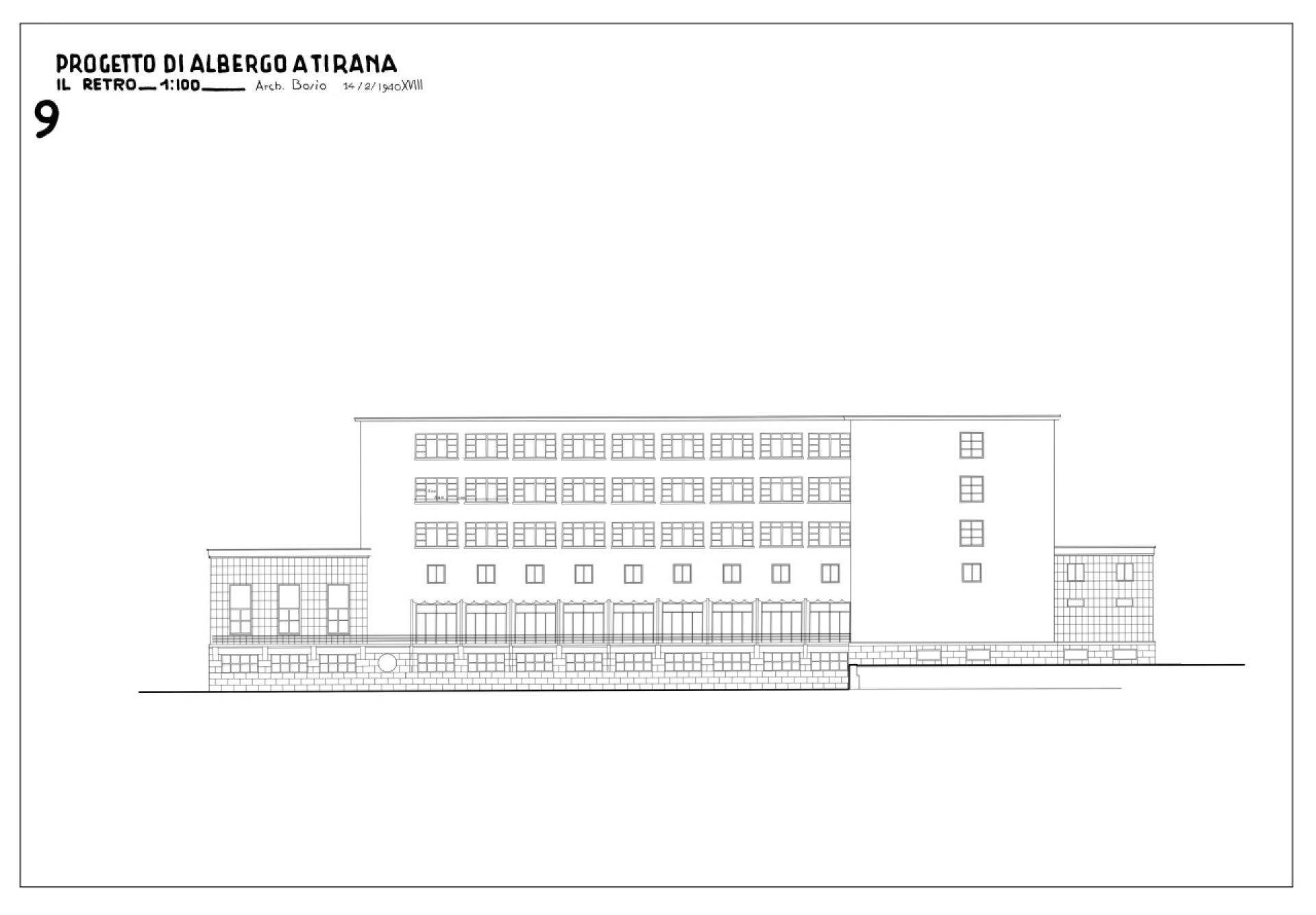

The commission for the Dajti Hotel was given to Gherardo Bosio, who was in charge of the General Regulatory Plan for Tirana and the detailed design of the Viale dell’Impero, today Martyrs of the nation Boulevard (Bulevardi Deshmoret e Kombit). Bosio situated the hotel at the boulevard’s crossing with Lana River, where the most representative buildings of the capital stood.

Decaying hotel, hidden behind trees on main boulevard. | Photo via Wikipedia

Hotel Dajti just after construction. | Source © Florian Nepravishta, AQTN

The hotel has to follow the design criteria of all the other buildings along the boulevard. Based on the urban regulations issued in January 1940, those criteria concerned primarily the volume, the continuity of the facades and their front length based on multiples of 4-meter modular distances, building width in proportion to road width and the stone cover of the base areas to give them a dignified appearance.

Bosio designed the hotel using a restrained and elegant architectural language. The legibility of this building is based on the contrast of pure volumes on different scales: first, this contrast is created by the distribution of the main corps containing the main programs of the hotel, and on a smaller scale, by carving solids and voids such as balconies and loggias at the level of facades.

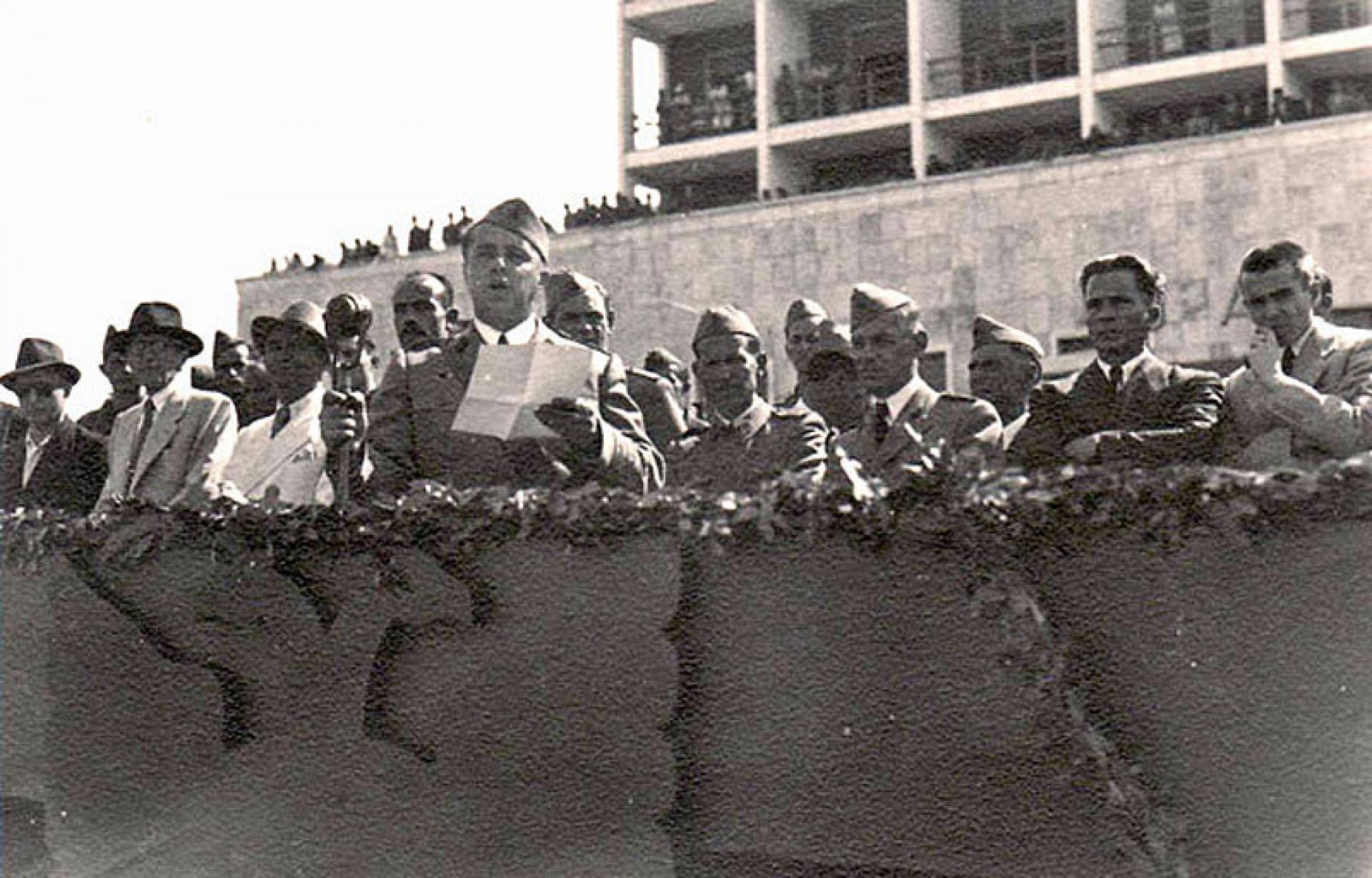

Enver Hoxha in front of Hotel Dajti, Tirana 10.7.1945 | Photo via Albanian History

A large staircase covered by a shelter, which bears the hotel sign, marks the entrance. While the base part is of marble, the upper body is plastered. To enhance and animate the appearance of the boulevard, the opening of continuous loggias on the top floors was advised.

The hotel is not in use anymore today. | Photo © Thomas Haemmerli

The interior, especially its public areas, reveal the complete modernity of the project and its elegance, which is characterized by rational organization of the spaces and clear legibility of the structures. The main hall impresses with light coming from the front and evokes a sense of eternity. Its double volume, supported by pillars, gives an impression of spatial grandeur.

City Logs exhibition by STEALTH.unlimited at the Hotel Dajti during the Tirana International Contemporary Art Biannual. | Photo © STEALTH.unlimited

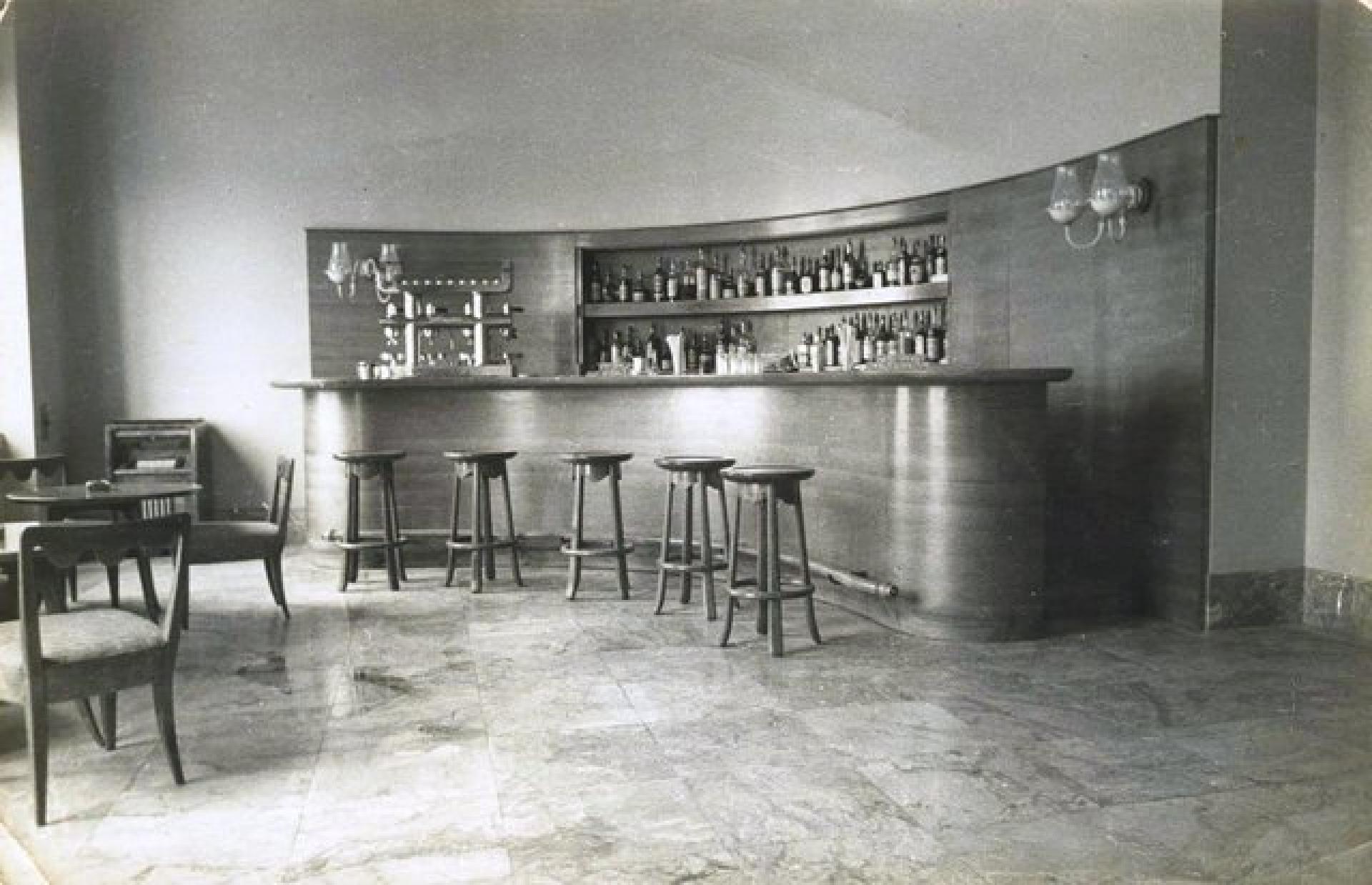

On the left side of the hall a staircase leads to the upper floor. The gallery overlooking the mezzanine, used for management offices, is clearly visible. The hotel also contains a basement with services, including a late-night bar internally connected with the ground floor bar.

The furnishing parts of the Dajti Hotel, designed in the early 1940s, were designed by Gio Ponti. | Source © Florian Nepravishta, AQTN

Dajti Hotel had everything it takes to be considered an avant-garde hotel. of that period. According to Giusti (2006), the area covered by this building that hosted, on one side, the new hotel and on the other, the offices of the Banca Nazionale del Lavoro, had a surface areas of 2000 m2. If we include atriums, parks and courtyards, the total area amounts to 12000 m2. Gazeta Tomori (in Giusti 2006) states that with i91 rooms and 125 beds, running water, bathrooms and all other amenities including a lift and dumbwaiters, Dajti was one of the largest hotels in the Balkans and the most modern in Europe.

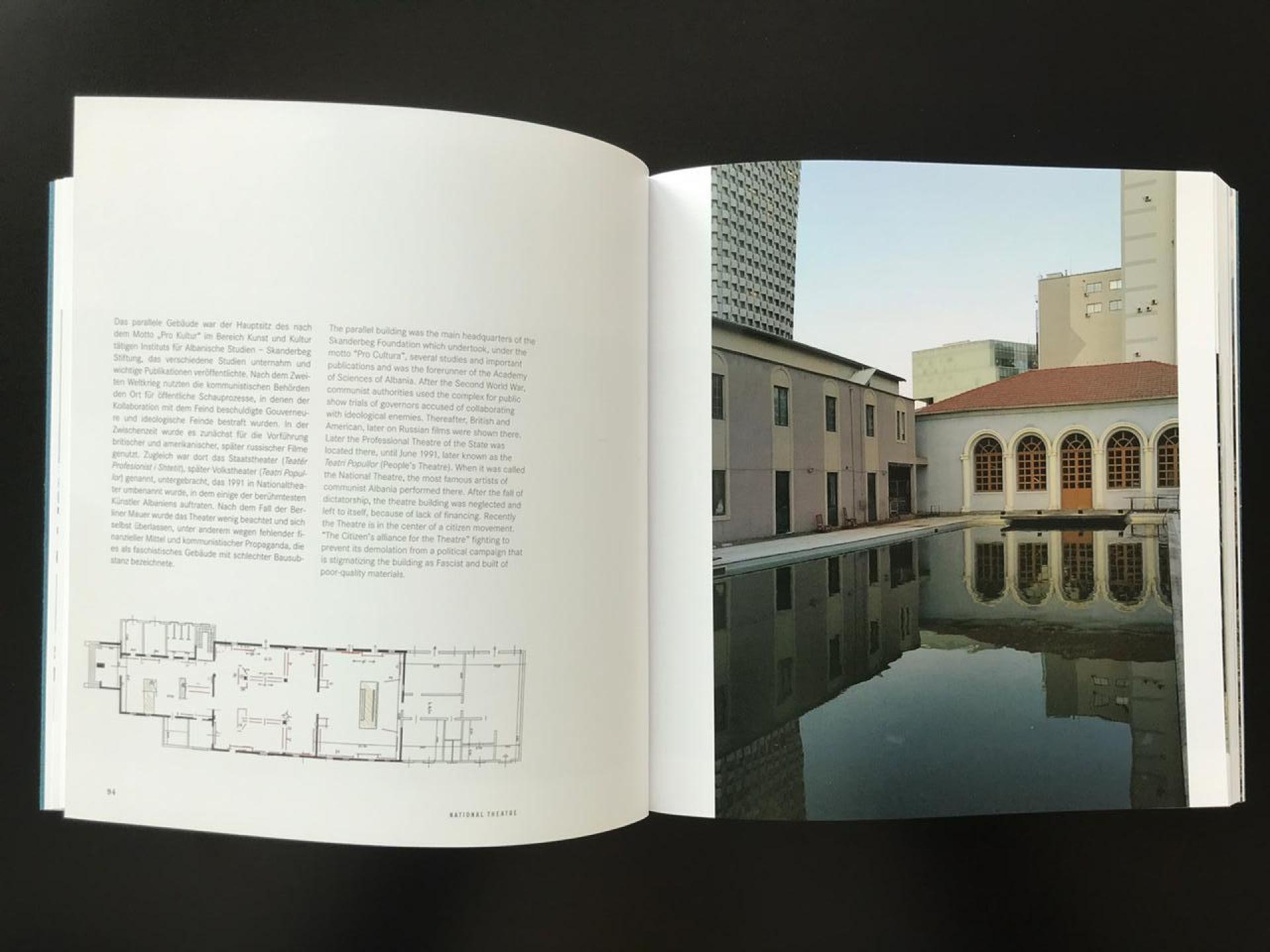

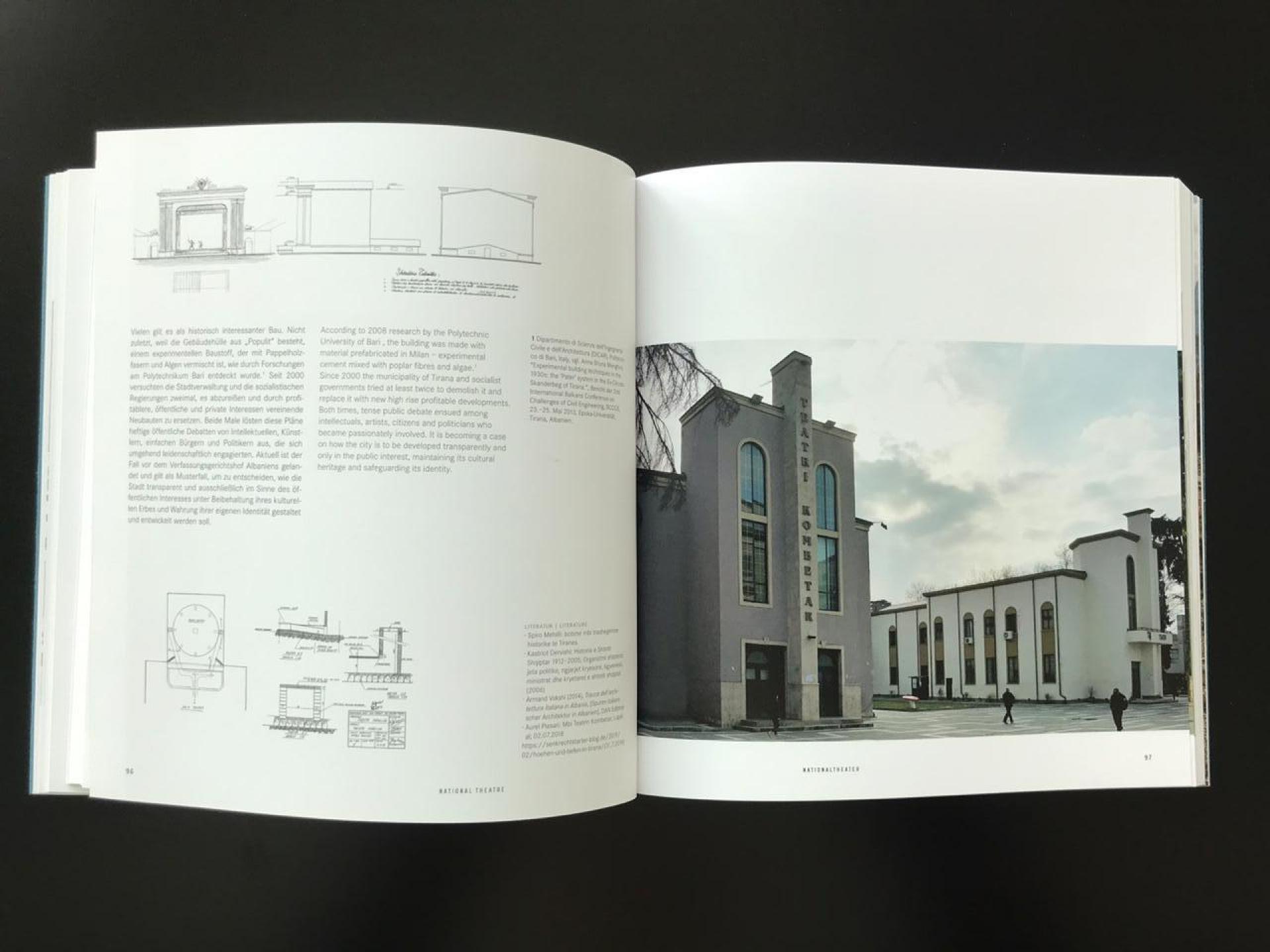

The National Theatre of Albania, built by the construction company Pater Costruzioni Edilizia and the Italian architect Giulio Berte, was completed in 1940. The project was part of the Italian strategy during the occupation of Albania between 1939 and 1943. Two main parallel buildings formed the complex, divided by a half-patio for relaxing, with a pool in the middle and a gym at the front end of the building. The architecture of the complex was based on the principles of the ventennio, as the twenty years of Mussolini’s regime in Italy are called. Initially, the left building was used as the Savoia Cinema for films, theatre and concerts.

The technical infrastructure was entirely suitable for cultural and public events because the building materials offered perfect conditions for acoustics and light technology. It was therefore for a long time also used for meetings and conferences. Albanians could here admire Greta Garbo, Laurence Olivier, Alida Valli, Anna Magnani and attend performances by the composers such as Vivaldi, Paganini, Chopin, Schumann, Verdi, Bellini and Donizetti, not to mention those of the most popular Albanian artists of that time.

The parallel building was the main headquarters of the Skanderbeg Foundation, which undertook several studies and important applications and the forerunner of the Academy of Sciences of Albania under the motto Pro Cultura. Communist authorities use the complex for public show trials or governors accused of collaborating with other enemies. The professional Theatre of the state was located in the building until June 1991 as the Teatri Popullor (People’s Theatre).

After the fall of dictatorship, the theatre building was neglected due to the lack of financing. Recently it is in the center of a citizen movement called The citizen’s alliance for the theatre, which is fighting to prevent its demolition from a political campaign that is stigmatizing the building as Fascist and built of poor-quality materials. According to the 2008 research by the Polytechnic University of Bari, the building was made with materials prefabricated in Milan composed of experimental cement mixed with poplar fibers and algae.

The building after construction. | Photo via Balcanicaucaso

Since 2000 the municipality of Tirana and socialist governments tried at least twice to demolish it and replace it with new high rise profitable developments. Both times, tense public debate ensued among intellectuals, artists, citizens and politicians who became passionately involved. It is becoming a case on how the city need to be developed transparently in the public interest and maintaining its cultural heritage and identity.

Actors in Albania have stormed the country’s national theatre to protest government plans to demolish the iconic building. | Photo via Teatri Kombëtar

Health-care facilities and hospitals are an architectural typology developed in Albania from 1958 to 1988. A number of different hospitals were erected in response to the needs of the country. General hospital centers were established in Berat, Gjirokastra, Tirana and Vlora, infectious disease units in Elbasan and Tirana, obstetrics and gynecology hospitals in Fier, Shkodra and Tirana, pediatric hospitals in Durres and Korce, neuropsychiatric hospitals in Elbasan, Shkodra and Tirana.

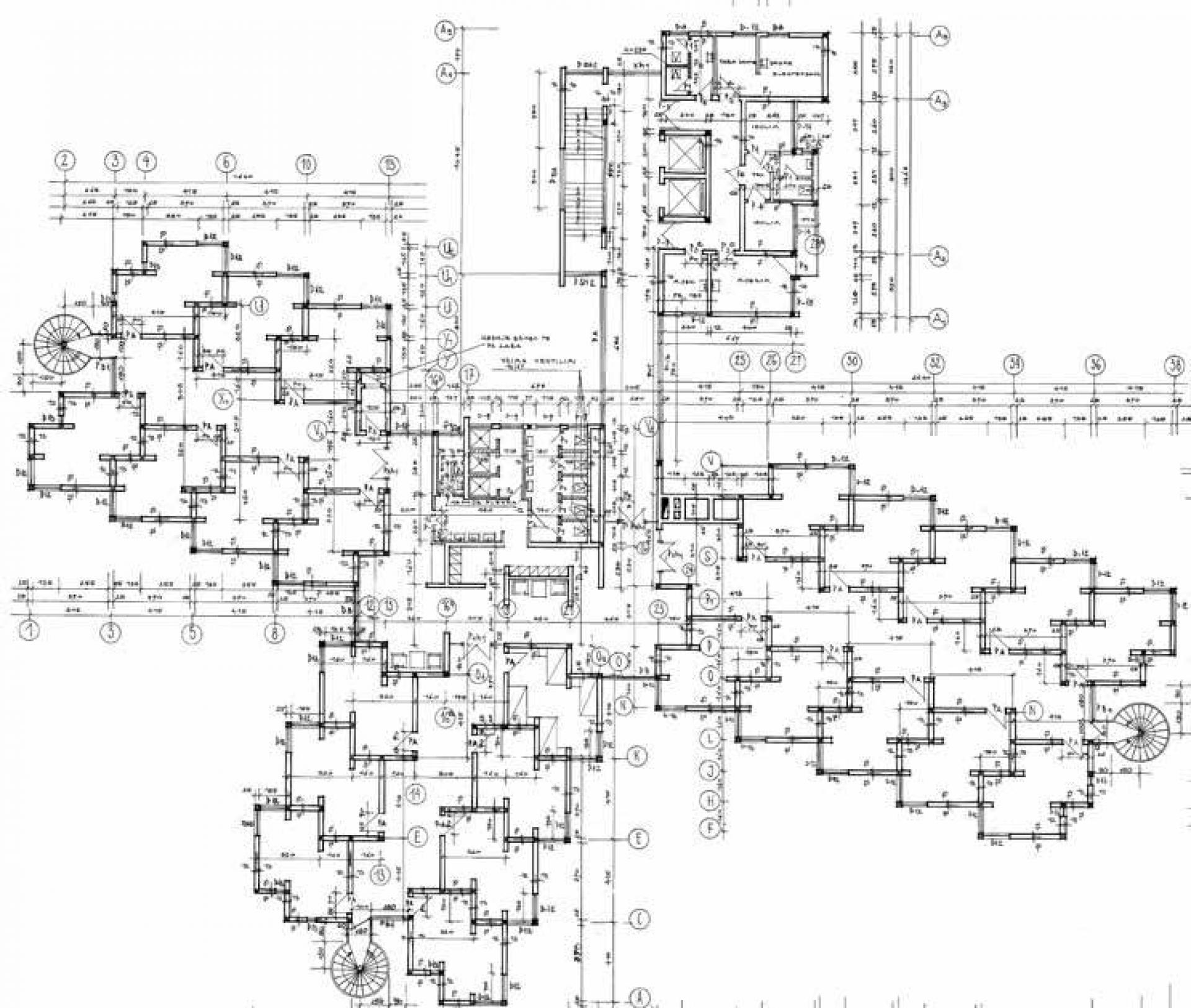

Known as the Psychiatric Hospital of Shkodra, the ensemble was designed in 1982 by Agim Myftiu and Mergim Cano. It is located in the north-eastern part of the city. The floor plan has the shape of a cross, with continuous staggered surfaces on the external perimeter but also in its interior spaces. The space is based on a repeated module consisted by a one room accommodating for patients.

Window openings that allow natural light are placed near the corners of the staggered volumes, creating a unique atmosphere different from that of conventional hospitals. That supports the recovery process of the patients. This particular way of staggering the facade opens new possibilities for the architectural composition of health-care facilities. The service block, developed as a strict volume, is a separate unit positioned on one side of the ensemble with a corridor connecting the two spaces.

The main entrance placed in the centre of the volume connects also several service entrances for the medical and administrative staff and in such way offers direct access to the various units. Apart from the main block of stairs in the service unit area, all floors accommodating patients are connected with stairs that are positioned in free-standing transparent cylindrical glass volumes. In the basement, apart from the heating and cooling systems, an underground refuge was built, a measure that was commonly taken during the dictatorship period to provide civilians with protection in case of attack.

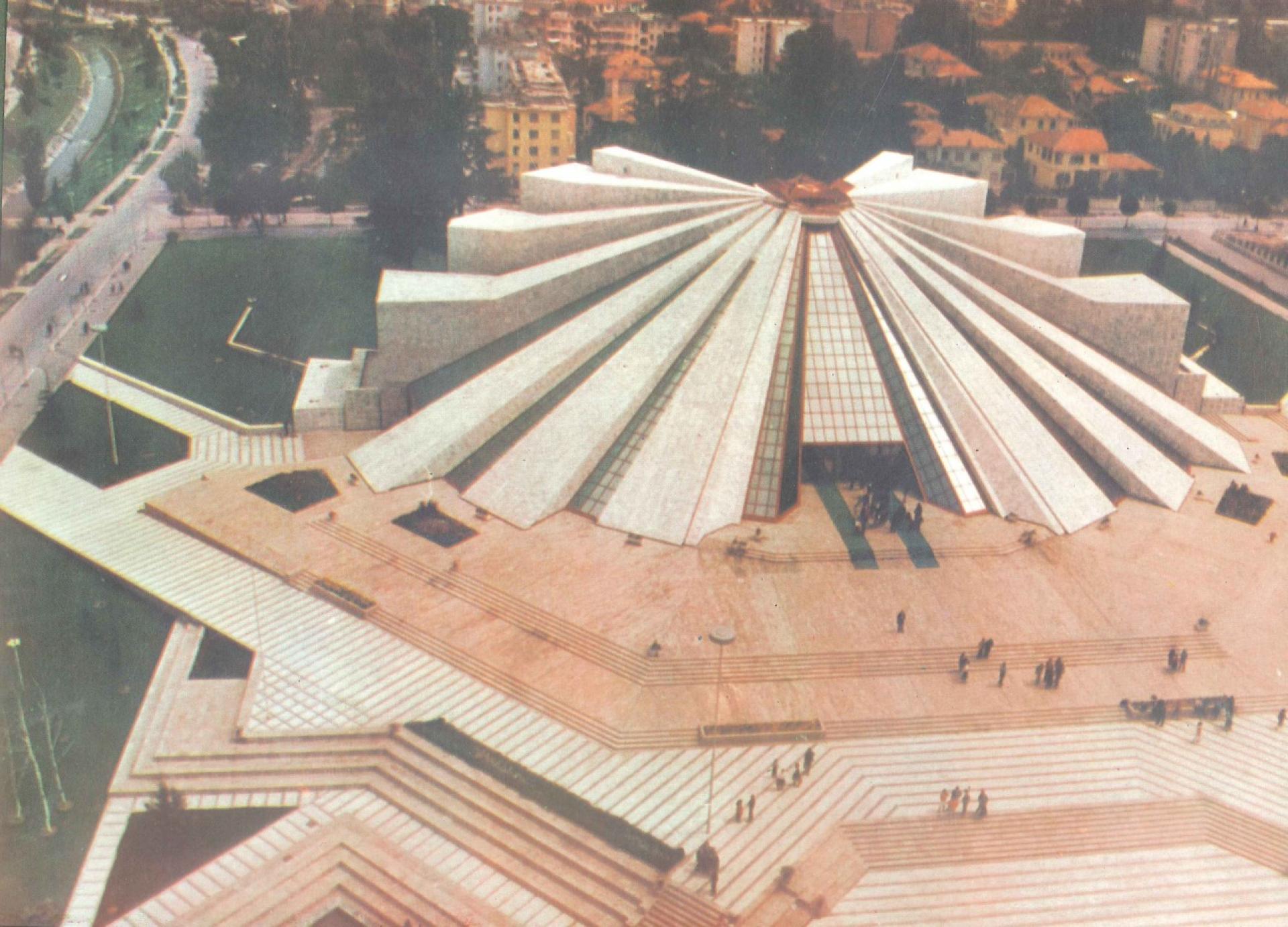

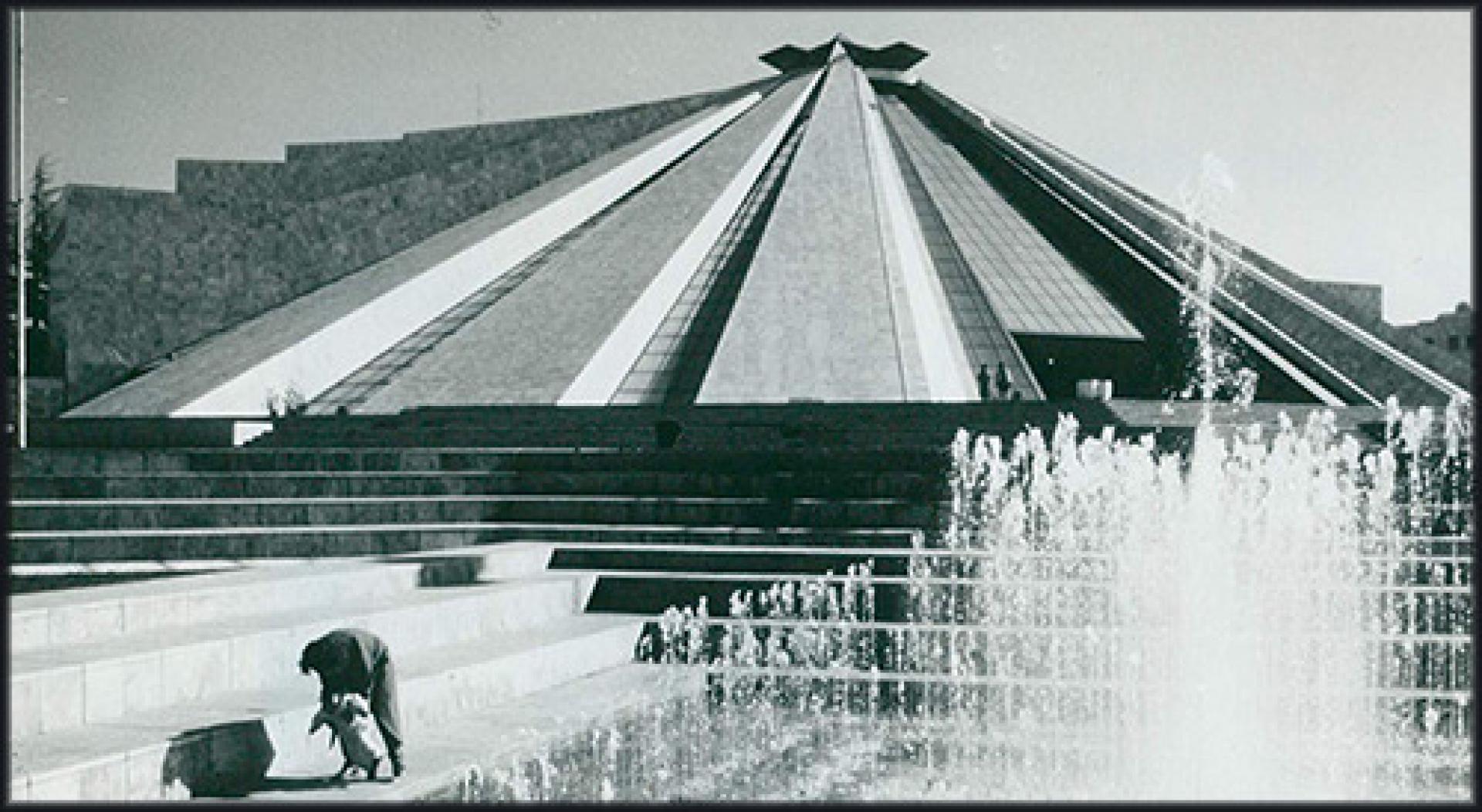

The main characteristic of Tirana’s city center is its monumentality with administrative, cultural buildings and public institutions concentrated along the main boulevard. In 1985, a pyramid building was erected on a former park, today known as Pyramid Square.

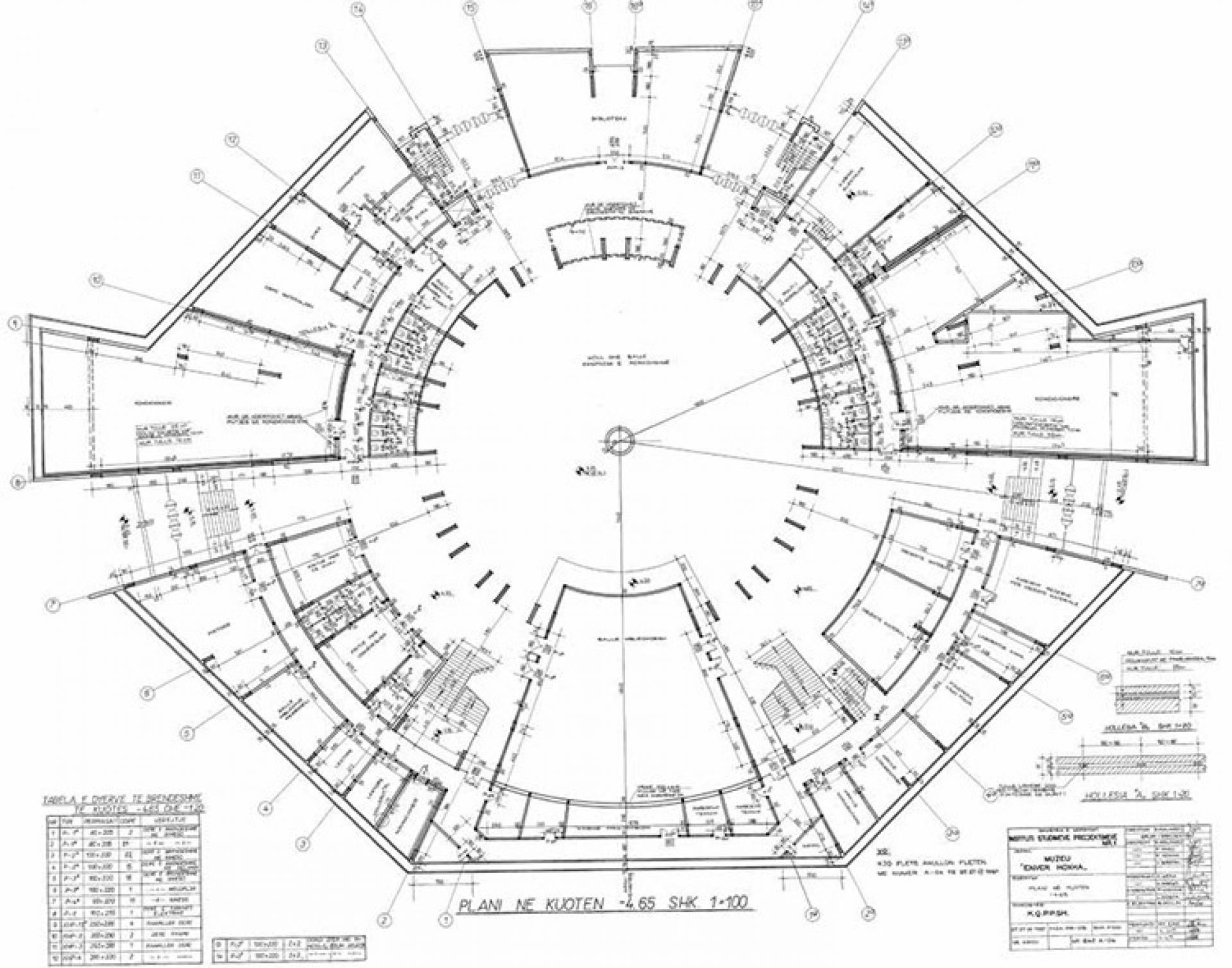

The Pyramid of Tirana was meant to house the legacy of the Albanian dictator Enver Hoxha. Four young architects were assigned to design the Enver Hoxha Museum. Klement Kolaneci, Pranvera Hoxha, Pirro Vaso and Vladimir Bregu had to respond to the urgent request to design a monumental new structure with potential sacral character to commemorate for eternity the dictator. The names are not completely occasional since among them are the daughter and the son in law of the dictator.

Designing a building, which was supposed to embody a sacral character, fulfill principles of social-realism and experiment with innovative forms proved to be quite a challenge. Before the project was selected, several alternatives that used the shape of the communist state as their main inspiration, resulting in designs that were too formal and naive were presented. Architects not only drew sketches, but built clay models to assist their understanding of the volumetric relationships.

The Pyramid’s location on the Tirana’s main boulevard between two iconic buildings, the Prime Minister’s office and the Dajti Hotel, required great sensitivity from architects. The architecture would need to respect the existing context of the boulevard and at the same time present a lithic echo of Mount Dajti, which has always been an important natural element of Tirana. Architects combined the socio-realistic principles (star shape, symmetry, processional stairs, raise into a pedestal, etc.) with a pure and articulated form attributing a modern aspect to the building.

The inclined façade of the Pyramid created an illusionary perspective, a unique feature at that time. The placement of the glass windows follows a radial composition around a central axis of rotation. The architectural volume rises 21 meters in height but appears lower due to the inclined planes throughout its exterior, series of platforms and stairs that lead from street level to the entrance. All that allow human scale to prevail. An inclined platform and an underground floor enable an additional entrance on the eastern side. Seen from above, the octagonal umbrella of the façade front is reminiscent of an eagle-wing shape. According to architect Pirro Vaso, architects’ main objective was to create impressive architecture while function played a secondary role. Consequently, architects didn’t choose a grid structure with separated floors but used an open plan, allowing later transformations of the interior space of 17,000 m2.

A marble statue of Enver Hoxha in the 1990s.| Photo © Barry Lewis/Corbis

High-quality imported materials and numerous expensive types of marble which covered the exterior and the interior of the Pyramid reveal the symbolic and ideologic importance this building had for the politburo in Albania. Over 4 million dollars are said to have been spent on this building in the 1980s, a time when the poverty level in the country was at its peak. The interior was designed to draw attention to the statue of the dictator, carved in pentelikon white marble (the same marble used for the construction of the Parthenon), at the center of the circular pyramid, which, like the statues of the gods in ancient Greek temples, was to demonstrate a divine presence, enhanced by the communist star on top.

The floor levels are designed as a series of platforms jutting out from the circumference and creating a big amphitheater with a white marble statue of the former dictator at its center. | Foto via Albania Pyramids

The characteristic structure allowed natural light to enter from all sides of the building as well as from a cupola at the very top filtering additional light through its glass cover. The realization of this structure was important not only due to its design and technological achievement but also because it expressed ideological and typological archetypes, such as the linear window development and the lack of vertical walls. As such, this project represents a conceptual shift in Albania at that time. The Pyramid served as a Museum for the dictator from 1988 until 1991. After the fall of the communist regime, the Pyramid was used as an exhibition and fair hall and the square in front became a venue for different public and private events until it was abandoned.

In 1992, the pyramid became the National Cultural Centre, while the square in front of it started to be perceived as a public space and was used by the citizens, becoming at the same time a main tourist attraction. Only after 2000 a discussion regarding the future of this monument began, from change of its function to a preservation as a living provocation reminiscent of the communist period and of course a demolishment.

The Pyramid in 1990s. | Photo via Universal Pictorial Press

However, it was decided to preserve it with a process of renovation that never came to an end. An international competition in 2007 proposed a transformation of the building into a drama theatre and center for the visual arts. Another competition from 2010, won by Coop Himmelb(l)au, proposed a demolition and exchange of the pyramid with a new parliament building in its place. None of the proposals has been realized. A public debate, petitioning and many protests took place in front of the building putting an end to the project and keeping the Pyramid on its place. Instead it become a ground for many experiments including competitions organized by Tirana Architecture Weeks. Lately, a new proposal for the Pyramid was presented by MVRDV intending to convert the former museum of the dictator into a new center for technology, art and culture.

-

Literature:

- Giusti (2006), Albania. Architettura e Citta 1925-1943, Maschietto

- Vokshi (2014), Tracce dell’architettura Italiana in Albania, DAN Editrice

- Hotelet para 1990, zhvillimi i tipologjise ne Shqiperi, Thomai, F., Nepravishta, O Borici, Shtyp Flesh, 2019.

- Spiro Mehilli: Botime mbi trashegimine historike te Tiranes.

- Aurel Plasari: Mbi Teatrin Kombetar, Lapsi.al 02.07.2018

- Spitalet Veshtrim tipologjik mbi arkitekturen shqiptare 1945-1990, Islami, Thomai, Marsida Tuxhari

- Xh. Kristo (2018), “Healing Spaces” Architecture space as regeneration of senses”, Diploma Thesis, POLIS University, Tirana

- Tirana – city of colours, sto Journal – aRK Magazine, UK, 2018

- Interview with Pirro Vaso, “Enver Hoxha” Museum, The Pyramid, 04.2019

- Të njihemi me Laureatët e Cmimeve të Republikës, Ndërtuesi Magazine Nr 83, Albanian Ministry of Construction, 1985

- Kastriot Dervishi: Historia e Shtetit Shqiptar 1912-2005; Organizmi shteteror, jeta politike, ngjarjet kryesore, ligjvenesit, ministrat dhe kryetaret e shtetit shqiptar. (2006)

- Dipartimento di Scienze dell'Ingegneria Civile e dell'Architettura (DICAR), Politecnico di Bari, Italy, VGL, A.B.Menghini, “Experimental building techniques in the 1930s: the ‘Pater’ system in the Ex-Circolo Skanderbeg of Tirana.”, 2013, Epoka-University, Tirana.

- S. Kristo, J. Dhiamandi, Albania is NOT an Island. The experimental framework of spatial and architectural interventions in Albania’s capital. ARCHITHESE, Architectural Journal.

All Photos (except the captioned) by © Saimir Kristo, Sonia Jojic, National Technical Archive of Construction, Albania

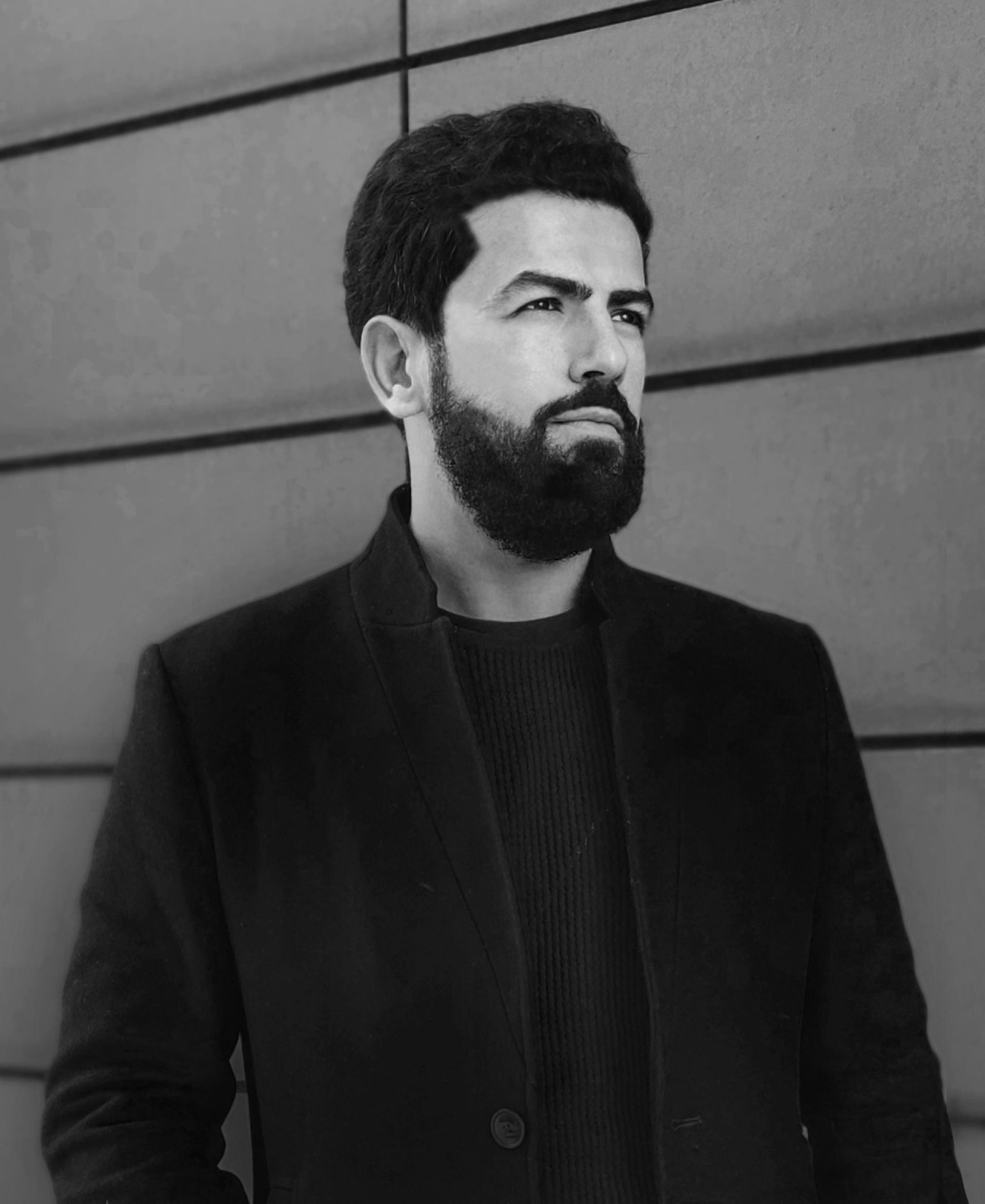

Saimir Kristo is a practicing architect, urban designer, lecturer and a Vice-Dean at the Faculty of Architecture and Design POLIS University. His PhD research was focused on city morphology, urban catalysis and public-ness, linked with his experience as the Director of several Regulatory Plans in Albanian cities supported also by USAID. Saimir is an alumnus of the International Visitor Leadership Program by the State Department of the USA and member of civil society. He is a dedicated cultural ambassador into enabling inter-cultural dialogue and collaboration between academia, culture institutions, museums, artists and community developing a common platform for discussion. He curated the two most important architecture and design events in Albania, Tirana Architecture Week 2014: Visioning Future Cities and Tirana Design Week 2015: Design NOW! He was selected as European Young Curator in the CEI Venice Forum for Contemporary Art Curators. He is an international critic and writer and board member of A10 new European Architecture Cooperative, FORUM A+P, Future Architecture Platform and organizer of PechaKucha Night Tirana. He is also a board member of Fundjavë Ndryshe Foundation, a philanthropic foundation that aims to diminish poverty in Albania devoting his skills as an architect building new homes or restoring old houses for Albanians in extreme poverty.